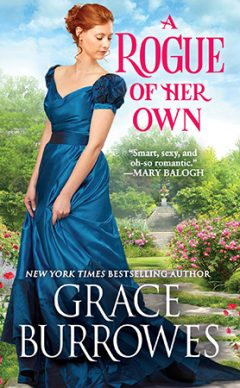

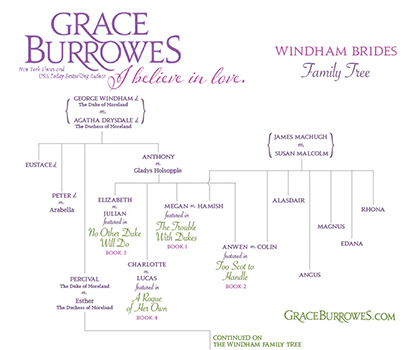

Too Scot to Handle

Book 2 in the Windham Brides series

Colin MacHugh is trying to come up to scratch as the brother and heir of a newly minted duke, but Polite Society isn’t keen on a former army captain acquiring even a courtesy title. At the suggestion of an aristocratic friend, Colin takes an interest in a charitable home for urchins. Miss Anwen Windham is devoted to the same institution, and as Colin and Anwen work together to save the failing orphanage, their interest in each other becomes passionate.

When the orphanage’s troubles take a criminal turn, everybody is suspect, from Colin, to the children, to Anwen. If Colin blows retreat and heads home to Scotland, the orphanage will surely fail. If he stays to fight the accusations coming at him from all sides, he could lose a future with Anwen–and his life….

Bonus Materials →

Enjoy An Excerpt

Chapter One

“It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single gentleman in possession of a great fortune—damn it woman,” Winthrop Montague bellowed, “where’s my ale?”

“And in possession of a title!” somebody called from across the tavern’s longest table.

“And damned fine looks!” his mate added.

“And a strapping bay gelding I’m keen to win over a hand of cards!”

Much rapping on the tabletop ensued, along with by-joves and hear-hears, until Lord Colin MacHugh’s head throbbed to the beat of all this gentlemanly bonhomie.

“As I was saying,” Montague went on, gesturing grandly with his tankard and sloshing ale on the floor. “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single gentleman in possession of a great fortune, must be in want of a passionate, beautiful, inventive, affectionate….”

“Mistress!” the company yelled.

“Two mistresses, so he don’t wear ’em out too quick!”

“When you have as much good fortune as Lord Colin, you should hire entire brothels and invite all your friends along as a gesture of charity toward the less fortunate!”

When you had as much good fortune as Lord Colin, you apparently were expected to hire the equivalent of entire public houses.

The harried young woman serving the dozen men who’d accompanied Colin and Montague from the club emerged from the kitchen for the hundredth time in two hours. She ferried a set of full tankards over from the bar, and swiped aside a lock of dark hair with the back of her wrist.

One of Montague’s friends pulled her into his lap. “I can’t afford a mistress, my lovely, but I can show you a very fine time for tuppence.”

“D’you suppose that’s why they call it tupping?” Baron Twillinger asked. He’d reached the philosophical stage of inebriation while his companion, Lord Hector Pierpont, was still in the amorous phase.

Colin was not inebriated, but he was profoundly bored.

“If your lordship don’t mind,” the tavern maid said, wiggling against Pierpont’s hold, “I’m not that sort of girl.”

“You’re all that sort of girl if the price is right,” Pierpont replied, chasing her chin with the puckered lips of a hungry mackerel. “Am I right?”

“You’re right,” Twilly replied. “I’m foxed.”

“My lord, please let me go,” the girl said, struggling in earnest.

“I’ll let you go, as soon as you let me come,” her gin-Romeo retorted, groping her breast.

“Pierpont.” Colin tried for that blend of condescension, good humor, and command that came so easily to the true aristocrat. “If she’s busy accommodating your prodigious appetites, she can’t very well tend to the rest of us, can she? And we will provide her much more than tuppence to keep the ale and port flowing.”

“He’s got your there, Pointy,” the baron said, raising his tankard. “A round to Lord Colin’s superior intellect!”

Pierpont let go of the girl, and from across the table, Montague acknowledged a competent display of authority—or wealth—with a slight smile.

Colin signaled the serving maid with a tilt of his head, and that gesture—perfected in cantinas and public houses all across Portugal, Spain, France, and the Low Countries—earned him her cautious approach.

Smart woman—smart, exhausted woman. This impromptu drinking party had started a good two hours ago, and so far, Colin had found it a waste of time, coin, and decent ale. One didn’t say that of course, not when one was a newly titled Scottish lord learning to keep company with English aristocrats.

“Have the stable boy bring my horse around,” Colin said, keeping his voice low. “I ride a blood bay, about seventeen hands with two white socks. Tell your master Lord Colin MacHugh would rather he served us himself from this point onward.”

“I’ll get a cuff on me ’ead for telling me master—”

“Pierpont will get you a babe in your belly,” Colin said, slipping the girl a few coins. “My brother is the Duke of Murdoch, and the publican will want to remain in my good graces.”

“The Duke of Murder?”

How Hamish hated that sobriquet, but Colin would use it to keep this serving maid from ruin.

“The very one, and if anything happens to him, that title becomes mine. Away with you now, love.”

She curtseyed and moved off, and because Colin was a newly titled lord in the company of his peers, he pretended to watch her backside as she sashayed away.

Then he yawned—the first expression of genuine sentiment on his part since he’d sat down with Montague and his friends.

***

Mr. Wilbur Hitchings heaved a sigh of such theatrical proportions, Anwen Windham suspected he’d rehearsed it.

“A lady of your breeding and refinement shouldn’t be bothered with financial matters,” he said, shuffling papers on the lectern before him, “though the general conclusion is simple enough: Charities need benefactors. Your good intentions are helpful and commendable, et cetera and so forth. Nevertheless, good intentions do not pay the coal man or keep growing boys in boots and breeches.”

Anwen refused to sit quietly and be condescended to as if she were a recalcitrant scholar. She set about straightening the rows of desks and chairs before Hitchings’s podium because the headmaster of the Home for Wayward Urchins couldn’t be bothered to restore order in the empty classroom.

“You were hired by the board of directors for your expertise in managing charitable establishments for children,” Anwen said. “How do you propose we address the shortage of funds?”

Hitchings peered at her over gold-rimmed half-spectacles. “Madam, I was hired because I have a firm grasp of the curriculum necessary to shape useful young men from brats and pickpockets. Financial matters are the province of the directors.”

Hitchings had a firm grasp of the birch rod and the Old Testament. At meal times, he had a firm grasp of his bottle of claret.

“Your efforts with the boys could not be more appreciated,” Anwen replied. “I had hoped, based on your years of experience, you might have fundraising suggestions for a lady who’d like to see the House of Urchins thriving well into the future—under your guiding hand, of course.”

She let that sink in—if the House of Urchins failed, Hitchings’s livelihood failed with it. A simple enough conclusion.

“Charity balls come to mind,” Hitchings said, flourishing a handkerchief with which to polish his spectacles. “Subscriptions, donations, that sort of thing. To be blunt, Miss Anwen, funding endeavors are the only reason directors bother having a ladies’ committee. Your feminine endowments allow you to charm coin from those who enjoy an excess of means. If you’ll excuse me, I have lessons to prepare.”

Anwen’s uncle was a duke, and her sister had recently married a duke. This preening dolt did not leave her wrangling desks and chairs while implying that her breasts and hips were to be flaunted to keep a roof over his head.

“I’m sure the lesson preparation can wait a few more moments, Mr. Hitchings. How much longer will our present funds last?”

He tucked the handkerchief away, and rolled up the papers from the lectern, as if a nearby puppy might require swatting. “Weeks, two months at best.”

In other words, as the social Season neared its conclusion, the orphanage would approach its end as well.

“Have you applied for other positions?” Anwen gave him her best, most saccharine blink. “I’d be happy to write you a character if need be.”

Hitchings stopped half-way to the door. “A character for me, Miss Anwen?”

“Your salary is one of our greatest expenses.” Hitchings’s remuneration, in addition to his allowance for ale, candles, and a new suit, exceeded the budget for coal by a handy 14 pounds 8 per year. “In the interests of economy, the directors could seek to replace you with a lesser talent.”

Hitchings might have been handsome in his youth. He had thick brown hair going gray at the temples, some height, dark eyes, and the rhetorical instincts of a classroom thespian. Middle age had added a paunch to his figure, though, and Anwen had never seen him smile at a lady or a child.

He smiled at the directors. Every time he saw them, he was smiling, jovial, and briskly uncomplaining about the social alchemy he claimed to work, turning society’s tattered castoffs into useful articles.

“Replace me with a lesser talent?” Hitchings smacked the rolled papers against his open palm. “That would hardly result in economy, Miss Anwen. Instead of budding felons learning the straight and narrow under the hand of an experienced master, you’d be feeding and clothing little criminals for no purpose whatsoever.”

Other than to save their lives? “I take your meaning, Mr. Hitchings, but the directors are men of the world, and they deal in facts and figures more effectively than I ever hope to. While you could easily find a post that more appropriately rewards your many talents, the boys will starve without this place to call home. I expect the directors will see that logic easily enough.”

Especially if Anwen reminded them of it at every meeting.

Hitchings’s mouth worked like a beached fish’s, but no sound came out. He doubtless wasn’t offended that his salary might be called into question, he was offended that Anwen—diminutive, red-haired, well-born, young and female—would do the questioning.

“I cannot be held responsible for the poorly reasoned decisions of my betters,” he said. “This organization is in want of funds, Miss Anwen, and what is the purpose of the ladies’ committee, if not to address the facility’s greatest needs? You can embroider all the handkerchiefs you like, but that won’t keep the doors open.”

French lace edged Hitchings’s cravat, his coat had been tailored on Bond Street, his gleaming boots were fashioned by Hoby. Anwen wished she had the strength to pitch him and his finery down the jakes.

“Thank you for putting the situation in terms I can grasp, Mr. Hitchings,” she said, adding a smile, lest he detect sarcasm flung in his very face. “Please don’t let me detain you further. You have lessons to prepare, and we must not waste a day of whatever time you have left to exert your good influence over the children.”

Anwen marched for the door, pausing to surreptitiously snatch up Hitching’s birch rod and tuck it into the folds of her cloak.

“You should probably finish tidying up the chairs and desks,” she added. “I have always admired your insistence on order in the boys’ environment. What better place to set that example than in your own classroom?”

She left at a brisk walk, ignoring the birch rod tangling with her skirts. Not three yards down the corridor, her grand exit nearly concluded with her landing on her bum when she ran smack into Lord Colin MacHugh.

***

Colin MacHugh liked variety, and not only regarding the ladies. Army life had offered a version of variety—march today, make camp tomorrow, ride into battle the day after—and just enough predictability.

The rations had been bad, the weather foul at the worst times, and the battles tragic. Other than that, camaraderie had been a daily blessing, as had a sense of purpose. Besiege that town, get these orders forward to Wellington, repair the axle on that baggage wain, report the location of that French patrol.

Stay alive.

Life as a lord, by contrast, was tedious as hell.

Except where Anwen Windham was concerned. Her sister Megan had recently married Colin’s brother Hamish, and of all Colin’s newly acquired English in-laws, Anwen was the most intriguing.

She crashed into him with the force of a small Channel storm making landfall.

“Good day,” Colin said, steadying her with a hand on each arm. “Are you fleeing bandits, or perhaps late for an appointment with the modiste?”

She stepped back, skewering him with a glower. “I am deloping, Lord Colin. Leaving the field of honor without striking a blow, despite all temptation to the contrary.”

The pistol of her indignation was still loaded, and Colin did not want it aimed at him. “Is that a birch rod you’re carrying?”

“Yes. Mr. Hitchings will doubtless notice it’s missing in the next fifteen minutes, for he can’t go longer than that without striking some hapless boy.”

They proceeded down the corridor, which though spotless, had only a threadbare runner on the floor. No art on the walls, not even a child’s drawing or a stitched bible verse. The windows lacked curtains, and the sheer dreariness of the place recalled memories of Colin’s years at public school.

“Sometimes a beating assuages a guilty conscience.” He’d had dabbled in the English vice, and quickly grown bored with it. He was easily bored, and the thought that the boys in this orphanage had only beatings to enliven their existence made him want to exit the premises posthaste. “I don’t suppose you’ve come across Lady Rosalyn Montague? I was to meet her here for an outing in the park.”

Miss Anwen opened a window and pitched the birch rod to the cobbles below. The building had once been a grand residence, the back overlooking a mews across the alley. A side garden had gone mostly to bracken, but the address was in a decent neighborhood.

The birch rod clattered to the ground, startling a tabby feasting on a dead mouse outside the stables. The cat bolted, then came back for its unfinished meal and took off again.

“Lady Rosalyn has a megrim,” Miss Anwen said, “and could not attend the directors’ meeting. Her brother was not among the directors in attendance either.”

“It’s a pretty day,” Colin said, rather than admit that being stood up without notice irked the hell out of him. “Would you care to join me for a drive ’round the park?”

Colin wasn’t about to tour the park by himself. Far too many debutantes and matchmakers ran tame at the fashionable hour for that magnitude of foolishness.

Anwen remained by the open window, making a wistful picture as the spring sunshine caught highlights in her red hair.

“I wish we could take the boys. They get out so seldom and they’re boys.”

Long ago, Colin had been boy, and not a very happy one. “Instead of punishing the miscreants with beatings, you should reward the good fellows with a visit to the park. For the space of a day at least, you’d see sainthood where deviltry reigned before.”

“Do you think so?”

“I know so. Will you drive out with me?” Winthrop Montague had all but begged Colin to take Lady Rosalyn for a turn. Alas, a gentleman obliged his friends whenever possible, even when the requested favor was infernally boring. Lady Rosalyn Montague had a genius for prosing on about bonnets, parasols, and reticules until only the promise of strong drink preserved a man’s wits.

An hour with Anwen would be a delight by comparison.

“I shall enjoy the air with you,” Miss Anwen said, taking Colin by the arm. “If I go back to Moreland House in my present mood, one of my sisters will ask if I’m well, and another will suggest I need a posset, and dear Aunt Esther will insist that I have a lie down, and then—I’m whining. My apologies.”

Miss Anwen was very pretty when she whined. “So you will join me, because you need time to maneuver your deceptions into place?”

She shook free of his arm and stalked off toward the end of the corridor. “I am not deceptive, and insulting a lady is no way to inspire her to share your company.”

Colin caught up with her easily and bowed her through the door. “I beg your pardon for my blunt words—I’m new to this business of being a lord. Perhaps you maneuver your polite fictions into place.”

“I do not indulge in polite fictions.”

The hell she didn’t. “Anwen, when I see you among your family, you are the most quiet, demure, retiring, unassuming facsimile of a spinster I’ve ever met. Now I chance upon you without their company, and you are far livelier. You steal birch rods, for example.”

She looked intrigued rather than insulted. “You accuse me of thievery?”

“Successful thievery. I’ve wanted to filch the occasional birch rod, but I lacked the daring. I’m offering you a compliment.”

If he complimented her gorgeous red hair—more fiery than Colin’s own auburn locks—or her lovely complexion, or her luminous blue eyes—she’d likely deliver a scathing set down.

Once upon a time, before Colin’s family had acquired ducal title, Colin had collected both set downs and kisses like some men collected cravat pins. Now he aspired to be taken for a facsimile of a proper lordling, at least until he could return to Perthshire.

“You admire my thievery?” Miss Anwen asked, pausing at the top of the front stairs.

“The boys will thank you for it, provided the blame for the missing birch rod doesn’t land on them.”

Miss Anwen had an impressive scowl. “Hitchings is that stupid. He’d blame the innocent for my impetuosity and enjoy doing so. Drat and dash it all.”

She honestly cared about these scapegrace children. How… unexpected. “We’ll have the birch rod returned to wherever you found it before we leave,” Colin said. “Hitchings merely overlooked it when he left the schoolroom.”

“Marvelous! You have a capacity for deception too, Lord Colin. Perhaps I’ve underestimated you.”

“Many do,” Colin said, escorting her down the steps.

He suspected many underestimated Miss Anwen too, because for the first time in days, he looked forward to doing the lordly pretty before all of polite society.

And before Miss Anwen.

***

“What news, Tattling Tom?” Dickie asked, pushing his hair out of his eyes.

As far back as they’d been mates, Rum Dickie had been asking for the news, and as best as Thomas could recollect, the news had always been bad.

“Hitchings will leg it in June,” Thomas said, which came close to being good news. He used a length of wire to twiddle the lock on the detention room door shut, then hid the wire among the books gathering dust on the shelves.

“So we’re for the streets by summer?” Dickie asked.

Wee Joe kept his characteristic silence. He was a good egg, always willing to stand lookout. Because of his greater size, he was also willing to take on the physical jobs such as boosting a fellow over the garden wall or putting up with Hitchings’s birchings.

“Miss Anwen is worried,” Tom replied, trying to condense what he’d overheard outside the classroom. “Not enough funds to keep us fed, and Hitchings hasn’t got any useful ideas where to get more blunt.”

Wee Joe remained by the window—the detention room had the best view of the alley, proof that Hitchings was an idiot. If you wanted to shut a boy up so he’d sit on his arse and contemplate his supposed sins, you didn’t provide him a nice view from a window with a handy drainpipe two feet to the right.

“Joe, come away from there,” Dickie said. “We’re supposed to be memorizing our amo, amas, amats.”

Joe pointed out the window, so Tom joined him.

“Cor, Joey. That’s a prime rig.” Not only did the phaeton have spanking yellow wheels, the couple on the bench looked like they came straight off some painting of Nobs Taking the Air.

“Miss Anwen got herself a flash man,” Dickie marveled.

Joe scowled ferociously.

“That’s Bond Street tailoring, Joe,” Dickie said, “and the best pair in the traces Tattersalls has seen this year. Spanish, I’d say, not Dutch nags.”

The gent got the phaeton turned about in the alley—no mean feat—and the team went tooling on their way.

“Haven’t seen him before,” Tom remarked, and as the designated intelligence officer in the group—Miss Anwen’s description of him—he prided himself on keeping track of names and faces.

“He’s Lady Rosalyn’s beau,” Dickie said. “Saw them at Gunter’s last week with Mr. Montague.”

That earned another scowl from Joe, who took a seat on the floor beneath the window. Joe was blond, blue-eyed, and not a bad looking boy, but he got cuffed a lot because he spoke so little. One of those blue eyes sported a fading bruise as a consequence.

“I know I shouldn’t have been out on me own,” Dickie said, “but I go barmy staring at these walls, sitting on me feak, listening to old Hitchings wheezing hour after hour. If Miss Anwen would come read to us more often, I might not get so roam-y.”

Restlessness affected all the boys, the longing to be back out on the streets, managing as best they could, free of Virgil and Proverbs—and Hitchings.

“What do you suppose Hitchings will do when this place runs out of money?” Dickie asked.

Hitchings wouldn’t last two days on the streets, but he certainly did well enough as the headmaster of the orphanage. Very well.

“Kick them with his new bloody boots,” Tom said, wondering what it felt like to put on a boot made for your own very foot.

Joe swung his open hand through the air, mimicking a slap delivered to a boy’s face.

“That too,” Dickie agreed. “Thank the devil we’re too big to be climbing boys.”

Joe motioned jabbing the earth with a shovel.

“The mines are honorable work,” Tom said, an incantation he’d overheard down at Blooming Betty’s pub.

“The mines will kill us.” John climbed in the window as he spoke, making one of his signature dramatic appearances. “I had uncles who went down the mines. They were coughing their lungs out within a year.”

He leapt to the floor as nimbly as an alley cat. The skills of a born house breaker went absolutely to waste in this orphanage, as did Dickie’s ability with locks, and Joe’s pickpocketing.

“Who wants a rum bun?” John asked, withdrawing a parcel from his shirt.

Joe shook his head.

“C’mon, Wee Joe,” John said, holding out a sweet, and folding cross-legged to the floor. “It’s a cryin’ damned shame when a man can’t work his God-given trade. Me own da often said as much.”

“Before the watch nabbed him,” Dickie muttered, snatching the bun. “You’ll get us all flogged to bits, John.”

“I’ll get us all a fine snack” John said around a mouthful of bun. “What was that gent doing here?”

“Same thing we all do,” Dickie said. “He was falling in love with Miss Anwen.”

“Lady Rosalyn won’t like that,” Tom said, tearing off a small bite of his bun.

“Lady Rosalyn won’t care,” John countered. “She’s so pretty, all the gents want her. I should have stolen more buns.” He eyed the window longingly, but remained where he was.

“Don’t leave crumbs,” Tom cautioned. “Hitchings will see them, and we’ll be locked up in the broom closet next time.”

The broom closet stank of dirt and vinegar, and the boys were never incarcerated there all together, the space being too small.

“Hitchings claims we’re running out of money,” Tom said, tearing off another tiny bite.

“Hitchings has to say we’re nearly broke,” John replied, dusting his hands. “He has to keep them pouring money into his pockets whether or not there’s money in the box.”

Tom studied his next bite of bun. “We could check. See what’s in the box. It’s been nearly a month. Never hurts to know the facts.”

Nobody contradicted him, but Tom well knew that sometimes, it hurt awfully to know the facts. He’d been the one to find his mum dead in her bed after the baby had died. That fact still hurt a bloody damned lot.

“I don’t mind it here, so much.” Dickie stuck his feet out straight in front of him. His trousers had no holes or patches, though the hems were a good three inches too short. His boots fit, and they almost matched. “For once, I didn’t spend all winter fighting for a place to shiver my nights away. That gets old.”

“Nobody coughing himself to death here,” John conceded. “Damned consumption gets hold of a place, next thing you know, everybody’s being measured for a shroud.”

“I say we should see how much blunt’s in the box.” Tom got to his feet and slouched against the wall near the window, not hanging out the window for all to see like some boys would.

“Shite,” he whispered, pulling the window swiftly closed. “Hitchings is off somewhere.”

“Whyn’t he go out the front door like usual?” Dickie asked, crowding in on Tom’s right. “Likes to be seen strutting down the walkway, showing off his finery, does our Mister Hitchings.”

Joe snatched up his Latin grammar. Tom, Dickie and John did likewise—Joe’s hearing was prodigious good—and a moment later, footsteps sounded in the corridor. By the time the door swung open, all four boys were absorbed in the intricacies of circum porta puella stat… or portal. Possibly portam.

What did it matter, unless the puella was pulchra and amica?

“He’s gone,” MacDeever said, holding the door open. “You have an hour of liberty, but don’t let Cook see you. One hour from now, you’re to be back here, looking sullen and peckish.”

“Thanks,” Tom muttered, hustling through the door. John and Dick followed him, Joe left last, bringing his grammar.

MacDeever looked fierce, and he had the most marvelous Scots growl to go with his white eyebrows and tidy mustache, but he frequently subverted Hitchings’s worst excesses, probably risking his own post in the process.

“One hour,” the groundskeeper said. “And if I see anybody shinnying down the drainpipe in broad daylight again, I’ll turn him in to Hitchings myself. What would Miss Anwen think if one of her boys were to break his head on the cobbles, eh?”

What would Miss Anwen think, if she knew that every so often, her boys broke into Hitchings’s strong box, and took a detailed inventory of the contents?

Chapter Two

Anwen loosened her bonnet ribbons and nudged her millinery one inch farther back on her head, the better to enjoy the beautiful day.

“Why don’t you take off your bonnet?” Lord Colin asked.

He drove with the subtle expertise of one who knew his cattle and his way around London. Both horses were exactly the same height, build, and coloring, and they moved with the unity of a team raised and trained together.

Anwen’s cousin Devlin St. Just, a former cavalryman who’d come into an earldom, would say these horses had an expensive trot. Muscular, rhythmic, closely synchronized, and to a horseman, beautiful.

“A lady doesn’t go out without her bonnet, Lord Colin.”

“Balderdash. My sisters claim to forget their bonnets when they want to enjoy the fresh air without wearing blinders. I have a theory.”

“Are you the scientific sort, to be propounding theories?”

He was the fragrant sort, though his scent was complicated. Woodsy with some citrus, a hint of musk, with a dash of raspberry and cinnamon. Parisian would be Anwen’s guess. Her sister Megan claimed Lord Colin was quite well fixed.

“I’m the noticing sort,” he said, lowering his voice conspiratorially. “I suspect you are too. A younger sibling learns all the best ways to hide and watch. My theory is that women wear bonnets so that men cannot be certain exactly which lady they approach unless the gentleman is confronting the woman head-on.”

He halted the horses to wait at an intersection before turning onto Park Lane, so heavy was the traffic. For a moment, Anwen simply enjoyed the pleasure of being out and about on a sunny day. Helena Merton and her mama passed them, and Helena’s expression was gratifyingly dumbstruck.

Anwen wiggled gloved fingers at the Mertons, the grown-up equivalent of sticking her tongue out.

“Maybe, your lordship, the ladies wear their bonnets so they are spared the sight of any men but those willing to approach them directly.”

Lord Colin gave his hands forward two inches and the horses moved off smoothly. “You would not have made that comment if any of your sisters were with us. Your sister Charlotte would have offered the same opinion, but you would have remained silent. If you were to pat my arm right about now, I’d appreciate it.”

“Whyever—oh.” Anwen not only patted his arm, she twined her hand around his elbow. “Helena fancies you?”

“That is the question. Does she fancy me, my brother’s title, my lovely estate in Perthshire, or any man who will get her free of her mother’s household? Your uncle is a duke, you’ve doubtless faced a comparable question frequently. How do you stand it?”

Even for a Scotsman, Lord Colin was wonderfully blunt. “I love Uncle Percy. There’s nothing to stand.”

That was not quite true. The social season was an exercise in progressive exhaustion, and each year, Anwen wished more desperately that she could be spared the waltzing, the fortune hunters, the at homes, the fittings, the…

The boredom.

“So every fellow who bows over your hand and professes undying devotion means it from the bottom of his pure, innocent, financially secure heart?”

Anwen had not endured a profession of dying devotion from a bachelor for at least three years, thank heavens.

“The gallant swains are merely being polite, as am I when I accept their flattery. You have younger brothers, am I correct?”

“Three, each one taller, louder, and hungrier than the last. The French Army at its plundering worst couldn’t ravage the countryside as thoroughly as those three when they’re in the mood for a feast.”

What would that be like? To have younger siblings? People to condescend to and look out for?

“You miss them, Lord Colin. I can hear it in your voice and see it in your eyes.”

The MacHughs whom Anwen had met—Hamish, Edana, Rhona, and Colin—were red-haired and blue-eyed. Anwen’s hair wasn’t red, it was orange. Bright, brilliant, light-up-the-night-sky, flaming, orange.

Her male cousins had dubbed her the Great Fire when she was six years old.

Lord Colin’s hair was darker than his brother’s, shading toward titian, and his eyes were a softer blue—closer to periwinkle than delphinium. Helena Merton would fancy herself in love with those eyes, while her mama was likely enthralled with the family title—a Scottish dukedom, no less—and the settlements.

“I miss my siblings,” Lord Colin said. “I miss home, I miss wearing clothes that don’t nearly choke a man if he wants to exert himself beyond a plodding stroll. I miss tramping over the moors with my fowling piece, and I sorely miss the smell of the wort cooking in the vats.”

Did he miss a young lady who remained back in Scotland longing for him?

“Be patient another two months or so, and you can return to your Highlands, your distillery, and your sheep, or whatever else you’re pining for.”

To look at Lord Colin, Anwen would never have suspected he was homesick. He had a ready smile, and his manner was a trifle flirtatious. A dimple cut a deep groove on the left side of that smile and made his features interesting. Everything else was in gentlemanly proportion, though his nose was a touch generous, while that dimple pulled his expression off center, in the direction of roguish.

When Frederica and Amanda Fletcher wheeled past, their brother at the ribbons of their barouche, Anwen lifted her hand in a more extravagant wave.

“My thanks,” Lord Colin muttered, as he guided the horses to the leafy beauty of Hyde Park in springtime. “Those two hunt as a pair, and a man can’t dance with just the one sister, he must stand up with each in turn. Now that Hamish has gone off on his wedding journey, I’m the only escort Edana and Rhona have, so I’m always on picket duty.”

A military term, though Mayfair’s ballrooms were hardly battlegrounds. “You served in Spain.”

“And in Portugal, France, the Low Countries. War is in some ways quite simple. Your equipment is a gun, a bedroll, and a few cooking implements, all of which you keep in good repair. You shoot at the fellows wearing enemy uniforms. You don’t shoot at anybody else. Makes for a pleasing sense of order. London in springtime is a regular donnybrook by comparison. I considered it my job to guard Hamish’s back, but now your sister has taken that post.”

Lord Colin reminded Anwen of herself in her third season. The first season was all excitement and adventure. Even if marriage wasn’t an immediate objective, it was at long last a possibility. In her second season, she’d enjoyed not being a debutante, not being so giddy and nervous.

In her third season, she’d started dressing for comfort instead of display, and learned that sore feet, a megrim, a head cold, all had their places on a young lady’s spring calendar.

Now, she simply endured, but for her work at the orphanage, which might soon close its doors for want of coin.

“You abhor idleness,” Anwen said as the press of carriages required the team to slow to a walk. “Is that because you’re in trade?”

The question was bold, but not quite rude between in-laws.

“I am, indeed, in trade.” Lord Colin sounded pleased about it too. “I gather some people expect me to sell my distillery and pretend I’m content to raise sheep. Hamish was given to understand that his breweries are also not quite the done thing for a duke. Good luck getting him to give up profitable enterprises.”

“Orphanages are not profitable.”

Lord Colin turned the phaeton onto a less crowded path, and the relative quiet was bliss. Anwen loved the boys, loved taking a hand in running the House of Urchins, but her time there today had left her frustrated.

And worried.

“Regarding profitable enterprises, I am in favor of wee hands doing wee tasks,” Lord Colin said, “but using children for the production of coin on a significant scale will never meet with my approval.”

His burr thickened when he spoke in earnest. When he and his brother had a difference of opinion, Anwen could hardly understand them.

“You don’t employ children?”

“Of course I employ children. The tiger, the boot boy, the scullery maid—”

“No, I mean in your whisky-making business. Do you employ children in your business?”

“Nobody under the age of fourteen, and not in quantity. Why?”

Drat the luck. “One doesn’t speak of financial matters.”

Lord Colin laughed, a hearty sound at variance with the stillness and greenery around them. In two hours, the park would be as busy as the surrounding streets, but the fashionable hour had yet to arrive.

“Financial matters are what make the world go ’round, Miss Anwen. You can bet that your uncle the duke and his duchess discuss financial matters, everything from the news on ’Change, to the budget for candles, to the latest attempt by Parliament to fleece the yeoman of his profits.”

Anwen had thought to enjoy a pretty day, but if she didn’t raise the topic of the orphanage’s finances with Lord Colin, then with whom could she have that discussion? The Windham ducal heir, the Earl of Westhaven, was the family accountant, but he was also…Westhaven. If Anwen brought up a financial matter with him, he’d smile sweetly, ask after her health, and admire her bonnet.

Oh, to be six years old and once again regarded as the tempestuous Great Fire of the Windham family.

“You’ve gone silent,” Lord Colin said. “I hope I haven’t given offense.”

“I’m thinking. My orphanage is in want of funds. I’d like to propose a means of addressing that problem to the directors, for they’ll tut-tut and such-a-pity while my boys are turned out onto the streets again. The lords will dash off to their house parties in July and their grouse moors in August, and the children will never know safety or security again.”

Some of the boys were eager for that fate to befall them, especially now that spring had arrived.

“You are asking me how an orphanage might raise funds?”

How refreshing. Lord Colin wasn’t laughing or peering down his nose at her.

“Indeed, I am. Mr. Hitchings advised me to hold a charity ball, bat my eyelashes, and hope the attendees are motivated to part with coin on the basis of my flirtation.”

“Many would be happy to part with coin if you held a charity ball.” Lord Colin didn’t come right out and say it: If you held yet another boring, predictable, dull, barely endurable charity ball.

Anwen wouldn’t want to attend, much less organize, such a gathering.

“Say I hold a ball. Then what happens next year when the funds are again exhausted? I repeat my performance? What if something happens to me? What if my simpering isn’t convincing enough? The children still have to eat, and they have nothing and no one without that orphanage.”

Anwen surprised herself with the vehemence of her response, but when both Lady Rosalyn and her brother had failed to attend today’s meetings, Lord Derwent, the chairman of the board of directors, had declared that without a quorum, he could only preside over an informational meeting.

Hitchings had informed them funds were running short. Fifteen minutes of throat-clearing and paper-shuffling later, the meeting had broken up with nothing decided and no plans in train.

“Has anybody told you that you’re fierce?” Lord Colin asked.

“Not since I was six years old.”

“Well, you are. Give me a moment to think, because in your present mood, only a well-thought-out answer will do.”

He’d not only taken her question seriously, he’d paid her a compliment. “Take as long as you need, Lord Colin. If the topic were easily addressed, every orphan in London would have a secure future.”

***

Silly and Charming—Scylla and Charybdis—were on their best behavior, suggesting Miss Anwen met with their approval. The geldings also liked Hamish and Edana, and they positively purred when Rhona accompanied Colin.

For Miss Anwen, they’d gone beyond purring to perfectly matching their steps, and spanking along at a trot Colin could have set his watch to. More than a few horsemen stopped to gawk, though in all eyes, Colin could see the question: Wonder what he paid for that pair?

“Has anybody explained the concept of interest to you?” Colin asked the lady beside him.

“As in, small boys have an interest in sweets?”

All boys had an interest in sweets of some sort. Miss Anwen had no brothers. No wonder her urchins fascinated her.

“Not quite,” Colin said. “If you wanted to borrow your sister Charlotte’s blue parasol, and she agreed, but said in return, you had to lend her your green parasol for an outing in two weeks, that would be an exchange without the financial version of interest.”

“We’d be trading favors, which we do all the time.”

“Correct. If Charlotte instead said that yes, you could borrow her parasol, provided that in two weeks’ time, she could borrow both your parasol and your favorite reticule, that would be a transaction where she was said to charge you interest.”

“The extra cost to me for borrowing her parasol is interest?”

“Exactly. You had better desperately need her parasol now, to be willing to give up your best reticule for a time in addition to your own parasol.”

Colin expected Anwen to change the subject, though he couldn’t make the explanation any simpler.

“How does this work with money, Lord Colin?”

Perhaps Miss Anwen had some Scottish blood back a few generations, though she’d lowered her voice on the word money.

“The same concept applies. Let’s say you know of a highly profitable shipping venture, but you haven’t any capital to invest at the moment—all of your money is committed. You come to me and agree that if I lend you a hundred pounds for a year, you’ll pay me back a hundred and ten pounds because you expect to make a hundred and fifty.”

“But you haven’t earned that extra ten pounds,” she said. “You simply made money off my ambitions.”

Colin turned the team for another circuit along the quieter paths. “Or I lost the entire sum as a result of your dodgy venture.”

“Hardly that. You’ll toss me into debtor’s prison if my scheme comes to nothing, have my goods seized, and probably know to the penny what I’m worth before you consider lending me a farthing.”

“What if you’re a titled lord,” Colin countered, “and I can’t toss you into debtor’s prison?”

“Then you’ll find some other way to protect your investment, or you won’t lend me the money. My orphanage cannot borrow money, Lord Colin.”

Miss Anwen had an intuitive grasp of how a loan worked, as did Edana and Rhona.

“Your orphanage can lend money,” Colin said, steering the horses to the verge and bringing them to a halt.

“The House of Urchins hasn’t money to lend. I haven’t any either.”

“Take the reins,” Colin said, passing them to her. “We’ll let the boys blow for a moment.” He climbed down and loosened the check reins enough that his geldings could steal a few mouthfuls of grass.

“You’re encouraging naughty behavior,” Miss Anwen said, passing Colin back the reins. “Horses aren’t supposed to graze while in work.”

“Did your cousin Lord Rosecroft the cavalry genius tell you that?”

“And my first equitation instructor, and every instructor, groom, stable lad, and cousin since.”

What a bloody lot of people she had telling her how to go on. “Ever stood at attention for three straight hours, Miss Anwen?”

She took off her gloves, untied her bonnet ribbons, and peeled the hat from her head.

The hat snagged on a hairpin, or a combination of hairpins. Colin intervened, carefully untangling silky locks from satin ribbons, and passing Miss Anwen several hairpins when she’d set her bonnet on the bench beside her.

“My thanks, sir.” She used the hairpins to secure a loose curl. “I’ve passed years tied to a posture board, spent hours with three books piled on my head. My finishing governess laced me so tightly I once fainted at the top of the steps. Papa discharged her, but she’d been with me six months at that point. When she left, all of my dresses had to be to let out.”

Miss Anwen turned her face up to the sun, though the phaeton sat in a quiet patch of dappled shade. She had a profile to make cameo artists weep, and the line of her throat was elegance personified.

She also had freckles. Faint, visible only if a man sat right beside her, and they could have easily been disguised with a touch of rice powder, but Anwen Windham had freckles.

Also a keen mind, and experience with physical tribulations Colin would never have suspected.

“When you took off your bonnet just now, how did it feel?”

She regarded him steadily. “Heavenly. It’s Elizabeth’s bonnet, and a touch snug when I do my hair as I have. I grabbed it by accident but didn’t want to be late for my meeting. If you weren’t sitting here, I’d…well. I will brush out my hair before changing for supper tonight.”

Colin wrapped the reins around the brake and used his teeth to pull off his right glove. He reached over to Miss Anwen’s nape and gently massaged her neck.

“How does that feel?”

She dropped her head forward, a soft sigh joining the afternoon breeze. “You ought not to touch me like that, even if we are practically family and no one is watching.”

They were not practically family. To emphasize his point—not to enjoy the exquisite feel of smooth female flesh beneath his fingers—Colin persisted for another moment.

“That’s what it feels like for my team when I release the check rein, and let the horses know that for a short time, they’re off duty. For five minutes, they can relax, grab a snack, rest mentally and physically, before getting back to work.”

Miss Anwen raised her head, but didn’t put her bonnet back on. “I tell Mr. Hitchings the boys need to get out. They can’t sit in a classroom hour after hour and be expected to attend much of anything. They’re children, not monastic scholars training to be anchorites.”

Colin withdrew his hand—he’d made his point. “And if the boys don’t get out, they’ll become querulous, and then Hitchings will punish them for squabbling and for lack of attention to their studies. Where did you find this old besom? He sounds like every grown man’s worst boyhood nightmare.”

“Mr. Montague said Hitchings was a quite a bargain, for the salary we’re paying him.”

“Winthrop Montague?”

“He’s the vice-chairman of the board, and Lady Rosalyn serves on my ladies’ committee.”

This interconnectedness of all parts of polite society was something like the army, or Highland clans. Everybody knew everybody, and that was sometimes a good thing.

Though not always. “I’m acquainted with Win Montague,” Colin said. “If he claims Hitchings was a bargain, then Hitchings was a bargain.”

Miss Anwen set her bonnet back on her head, and Colin wanted to snatch it away and toss it into the bushes.

“How do you know Mr. Montague, Lord Colin?”

“We served together, both captains.” Though that was years ago. Colin had passed through London a few times since mustering out, and once even called on Win, though Win hadn’t been home at the time. “Montague has been helpful, acquainting me with what’s expected of a titled gentleman of means.”

Miss Anwen tied her bonnet ribbons and slipped on her gloves. “And acquainting you with Lady Rosalyn?”

Colin wanted to pitch her knowing smile into the bushes too. “Yes.”

Lady Rosalyn Montague was a vision in blonde, blue-eyed pastels. Her movements were elegant, her laughter warm, her dancing made a man feel as if no one had ever partnered a woman more gracefully.

Colin liked to watch her, but he didn’t enjoy watching other men fawn over her. She expected the fawning, which brought Anwen’s earlier comment to mind: You simply made money off my ambitions.

Lady Rosalyn earned smiles off a man’s ambitions, though to be fair, she dispensed smiles as well—with interest of a sort Colin didn’t quite grasp but knew he would never pay.

“Lady Rosalyn is a friend,” Miss Anwen said. “She made her come out two years after I did, and is in every way an estimable individual. You would make a very attractive couple.”

That remark should be sent not into the bushes, but rather, tossed straight into the depths of the Serpentine.

“Don’t do that,” Colin said, passing the reins over and climbing down again. “Don’t treat me as if I’m some orphan bachelor because I’m wealthy and new to polite society. I like Lady Rosalyn well enough, but if it came down to a night of waltzing with her, or cards with my brothers…”

“Yes?”

He fiddled with the check reins, leaving them a few holes looser than was strictly fashionable.

“I’d leave the ball early. I’m not looking to get married, Miss Anwen. Not yet. Someday, of course. But not…Hamish has been a duke for a matter of weeks, and I can assure you, until the title befell him, I wasn’t considered half of an attractive couple. I was a presuming Scot, in trade, with airs above my station. Now I’m a lord. It unnerves a fellow.”

It also predisposed a fellow to babbling. Colin climbed back into the phaeton, mindful that his tone of voice had caught the attention of his horses.

“Now you know what the ladies put up with year after year,” Miss Anwen said. “We’re seen as nothing more than half of an attractive couple, good breeding stock, decent settlements. Nobody refers to us as gorgeous settlements, even if a lady is an heiress. The highest praise she’ll garner is ‘decent settlements.’ Be patient with the ladies, Lord Colin, for they are very patient with the gentlemen.”

Colin gave the horses leave to walk on, when he wanted instead to offer some teasing, charming remark.

And yet, he could not make light of Miss Anwen’s observation.

He’d watched his sisters over the past few months. Edana and Rhona had looked forward to enjoying the London social season for the first time, thinking to be more spectators than participants. Hamish had stumbled into a ducal title, Edana and Rhona were ladies by association, and enthusiasm had turned from glee, to wonder, to bewilderment, to disappointment.

Was anybody enjoying springtime in London?

“You were explaining to me about interest,” Miss Anwen said, “and about how that could make the orphanage solvent. Please do go on.”

“Right. Interest,” Colin said. “If you’re borrowing money, interest is a cost. If you’re lending money, that interest is a benefit, and that brings us to the topic of endowments.”

Miss Anwen listened to him as he prattled on, truly listened. One of her endowments was a keen mind, apparently, in addition to brilliant red hair, the airs and graces of a lady, and the heart of a lioness where her orphans were concerned.

Also skin so soft, Colin could recall the feel of it beneath his fingertips even as he waxed eloquent about the Rule of Seven.

***

“And here you are,” Lord Colin said, alighting from the phaeton. “Delivered to your very own doorstep.”

Anwen didn’t correct him, though this was not her doorstep. Did a lady ever have her very own doorstep, short of widowhood?

She wasn’t even alighting at her papa’s doorstep, for Mama and Papa were again off cavorting in the wilds of Wales, while Anwen and her sisters bided with Uncle Percival and Aunt Esther.

Lord Colin came around to assist her from the vehicle. Her descent was a precarious undertaking involving the use of several tiny metal footrests, and much gathering of skirts, until his lordship muttered something under his breath and swung her to the ground.

“My thanks,” Anwen said, stepping back. “Was that Gaelic?”

His smile was bashful and a bit naughty. “It wasn’t French. Allow me to see you inside.”

“What about the horses?” For he hadn’t a tiger to hold them or walk them.

“They will stand until the first snowfall.”

“Unless somebody comes along to steal them.” What was this propensity she’d developed for contradicting a gentleman?

He patted the offside beast. “They won’t budge for anybody but me or their grooms, not without creating a riot first. One learns a few useful skills in the army.”

Apparently, one did. Not even Devlin St. Just drove about without a tiger.

Lord Colin did the pretty for Anwen’s sisters, Charlotte and Elizabeth, then went on his way before they could inveigle him into staying for tea—thank goodness. Anwen needed to think, to work some figures, and to gather more information.

“Anwen Heather Gladys Windham, where have you been?” Elizabeth demanded, before his lordship had even climbed back into his conveyance. “Her Grace was about to send out the watch.”

The watch was Anwen’s three male cousins—Westhaven, St. Just, and Lord Valentine—all of whom were in Town for the season.

“I went to my meeting at the House of Urchins, exactly as I said I would,” Anwen replied as Charlotte led her by the wrist to the family parlor.

“That was three hours ago,” Elizabeth retorted, from Anwen’s other side. “We were afraid you’d been struck with a megrim, or a fever, or turned your ankle, or come to harm. Are you sure you’re all right?”

Any other time, Anwen might have admitted that a pot of peppermint tea would be welcome, because the day had been tiring. When peppermint tea became too much to bear, chamomile and lemon soothed the nerves. Ginger settled an upset belly. Lavender and valerian tisanes could quiet worry.

She had an entire apothecary of ploys with which to treat her family’s need to cosset her.

Anwen shook free of Charlotte’s grasp. “Do either of you understand compound interest?”

Charlotte and Elizabeth were both several inches taller than Anwen. They exchanged a dismayed look over her head that she nonetheless felt, and had been enduring intermittently since the age of seven.

“Were you out without your bonnet?” Elizabeth asked. “The sun was strong today, even though it’s not yet summer. Too much sun for yo—for a redhead is ill-advised.”

“I’ll take that for a no,” Anwen said, stopping outside the family parlor. If they got her in there, she’d be questioned until dinnertime, plied with tisanes, swaddled in three shawls, her feet up on a hassock.

“You don’t know how your settlements are invested,” Anwen said, continuing down the corridor, “and neither do I, but that’s about to change.”

“Anwen Windham, where are you going?” Charlotte nearly bellowed.

“I am going outside. It’s a beautiful day, and if you want to interrogate me about my afternoon, then you will have to come outside with me.”

The look bounced between them again. They pursed their mouths at the same moment and to the same degree.

“Those children at the orphanage are not healthy company,” Elizabeth said. “I know you think they can do no wrong, but their upbringing exposes them to all manner of foul miasmas, and without intending you any harm whatso—”

Anwen ducked through a pair of French doors and let them swing closed behind her. The resulting bang felt lovely, until she spotted Aunt Esther already occupying the bench in the folly.

“Come join me,” Aunt said. “It’s a marvelous day to escape for a moment into the garden.”

Behind the door, Charlotte and Elizabeth were looking concerned and keeping their voices down. Anwen crossed the garden with more haste than grace.

“How was your meeting?” Aunt asked as Anwen tossed herself onto the opposite wooden bench. The folly was latticed on two sides with roses not yet blooming, and Aunt made a pretty picture against the greenery. She was a duchess, but also a mother, political partner to Uncle Percy, a pillar of society, and a genuinely gracious person.

Anwen ought not to bother her, but the idea of returning inside…She couldn’t. Not today.

“My meeting mostly didn’t happen,” Anwen said. “We lacked a quorum, which I suspect is a polite way to say, the directors would rather frolic at their clubs like truant schoolboys than worry about orphans.”

“Your uncle would understand your frustration. Those same lords and honorables are equally cavalier about their parliamentary duties. Drives poor Moreland to shouting and pacing and all manner of colorful language.”

“Colorful language?” Uncle Percy was the doting, jovial complement to Aunt Esther’s grace and gentility. They were the perfect mature couple, the perfect duke and duchess.

Though at present, Aunt’s slippers were tidily arranged beneath the bench, her feet up in a pose more reminiscent of a Grecian goddess at her leisure than a proper duchess.

“Your uncle Percy was once an army officer, you know,” Aunt said. “A third son with limited prospects. A man of that ilk doesn’t raise ten children without infusing some variety into his vocabulary.”

Charlotte and Elizabeth were apparently content to let Aunt Esther deal with Anwen—for now. There would be questions over the last cup of tea in the parlor this evening, or over breakfast.

Or both. “Did you acquire a colorful vocabulary, Aunt?”

Aunt Esther snapped off a green tendril intruding into the folly. “Me?”

“You raised the same ten children, and you contended with Uncle.” Anwen’s papa was Uncle Percy’s younger brother, and Papa, while ever loyal, was occasionally exasperated with the duke, as were His Grace’s own offspring.

Delicate blonde brows swooped down. “I see your point. I resorted to German. My grandmother’s English was never very good, so my German is excellent. It’s a capital language for strong emotion.”

Anwen’s mother resorted to Welsh, and as a consequence, her children had a grasp of Welsh that exceeded their Latin and French.

“Perhaps I need to learn German,” Anwen said. “I’m much afraid my orphanage will close its doors this summer, and all because I don’t know how my settlements are invested.”

Maybe she did need some chamomile tea.

“Your settlements are in the cent-per-cents,” Aunt said. “The same as your sisters’ are, the same as my widow’s portion. I can have Westhaven explain the details, but you will not walk up the church aisle without first gaining a clear grasp of your finances.”

Why had Anwen’s own mother not explained this—why hadn’t her father?

“The orphanage is running out of money, and nobody seems bothered by this but me. As Lord Colin and I toured the park today, he explained to me that if I can raise money for the orphanage, I can invest that money, and use the interest rather than principle to look after the boys.”

“You would need a very great deal of money, my dear.”

“So you see the magnitude of the problem? If all I can earn is five percent interest, then ten thousand pounds is necessary to yield the five hundred I need for the boys. That is a fortune, and it’s a very small orphanage.”

Aunt was quiet for a long moment. “You always did enjoy maths.”

“I did?”

“Yes, which is why your maths tutor was the same fellow who’d worked with your male cousins. He’d done such a fine job with those three—and neither Devlin nor Valentine were naturally studious—that we brought him back from the north for you girls. Your uncle is not mathematically inclined, so it’s fortunate Westhaven shares your proclivity.”

The day had been unusual, with the meeting that didn’t happen, Lady Rosalyn’s absence, an unscheduled outing in the park, and now this conversation. By rights, Anwen should have been in her room, having a short nap—of two hours’ duration—before dinner.

She had neither time nor inclination to nap when the fate of children was at stake. “I want to hold a charity ball, Aunt. These boys matter to me, and yet, everybody holds charity balls.”

The duchess snapped off two more vines. Anwen braced herself for a lecture about God’s will, and the resilience of the lower orders, a woman’s place, or some such rot.

“Your cousin Devlin could easily have been one of those boys,” the duchess said. “His antecedents aren’t a secret among the family, and what if his mother had fallen ill shortly after his birth? What if one of her protectors had taken the boy into dislike? What if Percival had gone back to Canada instead of falling in love with me? I have worried similarly for our dear Maggie.”

“Precisely!” Anwen said, bolting to her feet. “Tom’s mother died in childbed, and there he was, eight years old, nobody to look after him. He’d done nothing wrong. Joe barely speaks, but he’s a good lad and quick, and quite sturdy for his age. John has man of business in his very blood, and Dickie really needs to be a valet, he’s so taken with fashion. They are good boys, and they’ll go back to picking pockets and housebreaking for want of money that so many could easily spare.”

“My dear young lady,” Aunt said, patting the bench beside her, “radical notions put roses in your cheeks. It’s quite becoming, though your uncle will despair of your politics.”

Anwen settled beside her aunt, soothed by the duchess’s fragrance. Aunt always smelled good—not sweet, fragrant, or feminine, exactly, though she was all those things—but virtuous, kind, good.

“Will Uncle let me hold a ball for my orphans?” The idea of planning a ball…The duchess held only one formal ball a year, and every woman and half the men in the family were required to assist with the planning.

Her Grace stroked a hand through Anwen’s hair. “It might surprise you to know that Westhaven keeps me on a strict budget for the season’s entertainments.”

No ball, then. Drat and blast.

“I’ll use my pin money, but it won’t go far.” While the directors got drunk over endless hands of whist behind the stout walls of their—

A little shiver skipped across Anwen’s nape as an idea tugged at the hem of her worries.

“Aunt, what if we held a charity card party instead of a ball? A percentage of everybody’s winnings could go to charity. We’d be asking people to while away an evening as they often would, though chance would favor the orphans at every game, rather than smiling exclusively on the winners.”

Aunt swung her feet down and sat back against the cushions. “I’ve never heard of a charity card party. Even high sticklers have no issue with a mention of coin when it relates to a friendly game of piquet.”

And by all means, the sensibilities of the high sticklers should be foremost when children were threatened with a starvation.

“Gentlemen control the wealth in this realm,” Anwen said. “An entertainment that caters to gentlemen has more chance of raising funds.”

Aunt toed her slippers on, studying the satin bows adorning them. “I am expected to contribute to the tone of the social season, and for years, my farewell soiree has been a landmark on polite society’s calendar. Perhaps it’s time to change landmarks.”

She rose, an impressively tall woman who carried herself with unfailing elegance, even in the confines of a folly.

The duchess began a slow circuit along the benches. “If I point out to Westhaven that my nieces need a project to distract them from Megan’s departure for Scotland, he should allow me to divert the funds I’d typically spend on the farewell soiree to your card party.”

The shiver had turned warm and hopeful. “This must be your card party, Aunt.”

“The Windham card party, then,” Her Grace said, staring off across the garden. “We have charity balls all the time, subscription balls, musicales…A card party will be novel, and attendance will be limited. We won’t have the expense of an orchestra or the headache of errant debutantes and drunken bachelors.”

The duchess resumed pacing. “We must be shrewd about the invitations, but not exclusive. Wagers should be capped at one hundred pounds, I think.”

Anwen began doing math. “How many tables?”

“If we set this up in the ballroom, we can easily have twenty-five tables, which means one hundred people seated at play and perhaps another eighty wandering the terraces, listening to Valentine’s music, or enjoying punch and a buffet.”

As the duchess considered ideas, dates, and potential guests, Anwen added her thoughts and listened to a pillar of society throwing herself into a charitable cause.

Would any of this have happened if Lord Colin hadn’t spent more than an hour explaining to Anwen how to put the House of Urchins on solid footing?

No, it would not. Anwen would be in the family parlor, her feet up, swilling chamomile tea, and thanking her sisters for their concern.

Much more of that concern and she’d go mad.

“What about Lady Rosalyn?” the duchess asked. “Shall she help us manage this affair? Her brother is a director, isn’t he?”

“Winthrop Montague is the vice-chair, so he’ll certainly be in attendance, but I think Lady Rosalyn would rather enjoy the play than involve herself in yet another committee. She’s as much in demand as a partner at whist as she is on the dance floor.”

Very much in demand, and Anwen wished her the joy of both undertakings.

“She’ll be invited, but not involved.” Aunt rang for a lap desk, and a pot of stout China black along with a plate of sandwiches. As the shadows lengthened across the blooming garden, and honeysuckle perfumed the air, the card party took shape.

Anwen stuffed herself with three sandwiches—they were small, and no helpful sisters appeared to remind her to eat slowly—and pondered a question she did not put to her aunt.

Lord Colin had been expecting to meet Lady Rosalyn at the House of Urchins, and he hadn’t quibbled at Anwen’s explanation of a megrim. Megrims happened, as did monthlies, bad fish, and all manner of ailments, but Lady Rosalyn had apparently made a rapid recovery.

As Lord Colin had gone off on a flight about compound interest—making money on making money, as he put it—Anwen had spotted Lady Rosalyn up beside Lord Twillinger in a fetching red-wheeled gig. Anwen had ignored her friend, for her friend had seemed intent on ignoring Lord Colin.

Had Lord Colin ever stripped off his gloves and caressed the back of Lady Rosalyn’s neck, and did it mean anything if he had?

Chapter Three

“Paying the excise man has helped our profits?” Colin asked.

Thaddeus Maarten removed his glasses and offered Colin a rare smile. “Your product is seen as higher quality. Paying the excise is apparently comparable to giving it a lordly title. Only the finest whisky can afford to turn up its nose at all the mischief most distillers consider a part of their trade.”

That mischief included arrests, searches, explosions, incarcerations, fines, and bribes. Colin had watched his various cousins and competitors play fox and geese with the excise men for years. One cousin had lost a hand when a still had been blown up, another had emigrated to Boston one day ahead of an arrest warrant.

Colin’s involvement in whisky-making had started with an uncle’s urgent request to assist with repairs to a still the excise men had disabled.

“Ironic, that paying taxes should give my whisky respectability,” Colin said, coming around the desk to take a seat by Maarten. “I started paying the government tithes out of youthful pigheadedness. I was determined that my business operations would go forward without the drama my relations seemed to thrive on. One wants a challenge, not a constant threat of annihilation.”

Even as a soldier, the threat of annihilation had been only intermittent. Wellington had lost as many soldiers to disease as to enemy fire, and those who gave their lives in battle had done so for a reason more lofty than some yeoman’s dram of the day.

“No argument there,” Maarten said, tucking his glasses away. “I was determined to gain my freedom.”

Maarten had been born in Georgia, the offspring of a wealthy landowner and a house slave. How he’d arrived to Britain and acquired the education of a man of business was a mystery. Quakers had been involved, and violations of various laws, in addition to determination, luck, and a prodigious intellect.

“You wanted your freedom, and I long to leave the most civilized city in the world as soon as may be,” Colin replied, getting to his feet. “Here in London, I spend my evenings with men who sit in one place, never stirring for hours except to piss, and then they might go no farther than the chamber pot in the corner to relieve themselves—aiming badly because that’s hilarious, I might add.

“They jeer at each other like schoolboys,” he went on, “and call themselves witty, bother the tavern maids, and label themselves dashing, while soldiers who gave a limb or an eye for the safety of the realm sit cold and dirty in the street, begging for alms. I miss Scotland, where I was merely expected to work hard and keep my younger brothers out of trouble.”

Oddly enough, Anwen Windham had made that plain to Colin on yesterday’s outing in the park. In a moment, she’d clearly seen his longing for home, while Colin had only been able to identify a restless discontent.

“You spend some evenings waltzing,” Maarten observed. “And flirting.”

“I’m expected to escort my sisters, and flirting is part of what a titled gentleman does.” The flirting was easy, except Colin preferred to flirt with women who were free to flirt back. Ennui was fashionable among the ladies aspiring to sophistication, and the debutantes…

They were the recruits to the ranks of society, the foot soldiers living in fear of a stain on their new uniforms or a blunder on the battlefield. Thank God and Scottish governesses, Eddie and Ronnie were made of sterner stuff.

So was Anwen Windham, for all her soft skin and clipped English diction.

A tap sounded on the door.

“Enter,” Colin called, for his meeting with Maarten was concluded, and the sensitive information safely stowed in Maarten’s satchel.

“Mr. Winthrop Montague has come to call, my lord,” the butler said. “Shall I inform him that you’re not at home?”

Colin wasn’t at home—Perthshire was home, not this dwelling that was at once stuffy and much too big for three siblings and some staff.

“Send him up,” Colin said. “He’ll probably expect a tea tray, or lunch on the terrace, or some sort of free food and drink.”

“Very good, my lord.” The butler—a venerable relic by the name of MacGinnes—bowed.

“I should become seasick in his position,” Colin said, when MacGinnes had silently withdrawn and silently pulled the door closed. “All that bobbing and bowing.”

“How did you stand the army?” Maarten asked. “All the saluting and shooting?”

“Every job has its challenges.” Colin extended a hand. “My thanks for the report, and for all you do to make my enterprise successful. I’ll see you again, Tuesday next.”

“I’m planning to return to Scotland by the first of May,” Maarten said. “One doesn’t like to leave the distillery unattended for too long.”

Maarten was being delicate. Scottish law did not recognize slavery in any form, but English courts had dodged the matter, ruling only that former slaves could not be forcibly removed from England. Maarten could easily be snatched from some quiet London street and sold for a pretty penny in the West Indies.

“Maybe by the first of May, Eddie and Ronnie will have reached the limit of their fascination with fashionable society,” Colin said. “I’d love to travel north with you.”

“We won’t tap the ’89 until you’re back home where you belong.” Maarten buckled his satchel closed. “I already sent word that the duke is to be gifted with a barrel of the ’93.”

“The Duke of Moreland?”

“Your brother—the Duke of Murdoch.”

“Right.” And wrong too, somehow. Hamish was Hamish, and no more enamored of having a title than Colin was.

MacGinnes’s tap sounded on the door again.

“Come in!” For God’s sake.

“No need to announce me,” Winthrop Montague said, dodging around MacGinnes. “Oh, sorry. I didn’t realize you had company.”

Montague peered at Maarten as if not quite sure Colin’s man of business was animate.

“Mr. Maarten and I were finished with our meeting,” Colin said, rather than subject Maarten to an introduction. “Maarten, my thanks, and please do start on your travel arrangements. The ’93 for His Grace is an inspired notion. Perhaps we’ll name the ’89 for the duchess.”

Maarten bowed and withdrew, never so much as making eye contact with Montague. MacGinnes drew the door closed, and Colin wrestled with a longing for a wee dram.

Not the ’89, which would be lovely beyond imagining.

Not even the ’93, a whisky worthy of a duke.

Any damned whisky would do, provided it took the edge off his restlessness.

“That’s your man of business?” Montague asked. “He’s different.”

“Try to entice him away from my employ and I’ll call you out,” Colin said. “Maarten is shrewd, honest, hard-working, good with the men, and not prone to consuming my inventory.”

Montague took the seat behind Colin’s desk, because where else would a lordling choose to sit? “You’re not joking, are you?”

“I found him working in one of my warehouses. He brought to my attention a discrepancy between items on hand and items supposedly delivered from another of my warehouses.”

Montague opened the drawer to his right—even Edana and Rhona wouldn’t have been so bold. “Have you any snuff? I’m in need of a dose. Going a bit short of sleep these days.”

“I don’t partake. Shall we be off?”

They were to ride in the park at the fashionable hour, there being safety in numbers, according to Montague.

“You don’t fancy a late luncheon before we go? The weather is fair, meaning this won’t be a short outing.”

Typically English of the weather to be so disobliging. “A footman can lay out a tray for us in the garden. If you fancy ale, I’ll have that served instead of tea.”

“Please, God, some decent ale,” Montague said, lounging back in the cushioned chair. “Just how many warehouses do you own?”

“Six, and I trade shares in six others.”

“Twelve—? You own shares in twelve different warehouses?”

“I have a theory,” Colin said, heading for the door. “Where the whisky ages has a lot to do with its flavor. A cask stored high in a warehouse near the sea will have that scent, that freshness and brine. One tucked away in a Highland glen will bring the mountains into the nose or the finish. Sometimes, the sherry or port previously stored in the barrel overpowers the palate, but before and after, that’s where the subtleties sneak in.”

“One can hardly understand you when you wax poetical about your barbarian libation,” Montague said. “You put me oddly in mind of the temperance ladies when they’re on about demon rum and blue ruin.”

He gave a mock shudder as they emerged onto the back terrace, though the English temperance society hadn’t been convened that could outdo its Scottish cousins for zeal.

“Are you sure we have to idle about in the park this afternoon?” Colin asked. “I have some correspondence to see to.”

Montague had taken pains to instruct him on this point. A gentleman did not announce to even his friends that he craved to work on estimates for pricing and distribution of his finest whisky yet. A gentleman tended to correspondence.

Just as a gentleman was home when he wasn’t home, and was not home to certain callers when he was perched on his rosy fundament within earshot of his own front door.

All very confusing, this gentlemanliness. Colin wondered if his sisters, in their private moments, found being ladies equally trying.

“Of course we must be out and about this afternoon,” Montague said, clapping Colin on the shoulder. “If you are to take your proper place in society, you must acquaint yourself with the leading lights of that same body. Most of them are to be found in two places.”

Colin could recite this lecture by heart, but instead gestured to the table in the shade of a balcony.

“A gentleman,” Montague went on, “enjoys the company of the fairer sex on social occasions, and the carriage parade is a highly social occasion. He enjoys the company of his fellows at the clubs and sporting venues. Have you let it be known you’d like to join Brooks’s yet?”

Colin took a seat, though he wasn’t hungry. “You’re not a member. Why should I become one?” At great expense and bother, when he was already a member at three other clubs. Then too, Colin could easily be blackballed, and his failure to gain membership would become the subject of talk.

Polite society seemed to exist primarily to talk about itself.

“You must join,” Montague said, appropriating the chair at Colin’s right and flipping out his tails with enviable panache, “so that I can take my proper place with you there. Your brother is a duke, therefore you should have no trouble gaining access. If you aspire to Whig politics, and I suspect you do, then Brooks’s is de rigueur, old chap.”

Colin did not aspire to Whig politics, though Montague did. Younger sons stood for the House of Commons, or became vicars, diplomats, or military officers. Montague wasn’t interested in serving in Canada or India, and Colin couldn’t see him managing in a parsonage.

“I adore a rare roast of beef,” Montague said, tucking into the offerings on the tray. “Let’s have some ale, shall we? No rule says a pair of bachelors can’t wash down an afternoon repast with ale.”

Colin caught the eye of the footman standing in the sun near the door. “Ale, if you please, and have Prince Charlie brought around.”

“Of course, my lord.”

“Montague, if you’re not interested in socializing with a particular lady, why bother with the carriage parade? We ran that drill on Monday.” And the Friday before that, and the Tuesday before that.

Montague paused with a quarter of a sandwich halfway to his mouth. “Do you or do you not have a grasp of what marital relations entail?”

“Don’t be insulting.”

“Right, so. One marries, and the immediate benefit therefrom is obvious even to Scottish courtesy lords with more warehouses than I have fingers. If one marries shrewdly, then one acquires a papa-in-law who might finance a political campaign, tuck a little estate or two into the settlements, or include a doting son-in-law in his more lucrative investments. If one sires an heir to the family title, then the emoluments proliferate along with spares. It’s all quite lovely.”

To Colin, it all sounded damned boring. He’d go along on this scouting mission in Hyde Park because Anwen Windham might be among the ladies taking the air, and he had some potentially useful ideas regarding her orphanage.

“I have a business to run,” Colin said as the rest of Montague’s sandwich met its fate, “in addition to two estates, and no political aspirations. I have no need of a doting papa-in-law.”

Eating, drinking for free, and scheming to eat and drink for free seemed to be the measure of an aristocratic young man’s ambitions—with the occasional stupid wager, idiot horse race, or mindless tup thrown in for variety.

Oh, and waltzing. Mustn’t forget the waltzing.

“MacHugh, I’m sure in Scotland you’re justly proud of your accomplishments and wealth, but here, you must temper your pride with some—ah, just in time, my good man, just in time.”

The footman set a tray with two foaming tankards before Montague.

Montague lifted one, blew the head off, and managed to spatter the footman’s slippers with flecks of ale.

“You’re excused,” Colin said. If any force of nature equaled an English lordling’s quest for meaningless diversion, it was the English servant’s quest for decorum.

“You’re not drinking?” Montague asked, patting his ale mustache with his serviette.

“Not if we’re to leave for the park straightaway. You’re welcome to mine, of course.”

“Don’t mind if I do,” Montague said. “Now, see here, MacHugh. You’re looking a bit down in the mouth, and that won’t serve. I know all this socializing and smiling is tedious, but this is how you gain entrée where it matters. You can count on me to ease your way up to a point, but then the work falls to you, my friend. You’ve made great progress, and I daresay having your ducal brother away from Town can only benefit you. He was a bit of an original.”

And that was a bad thing? That a man didn’t toady to society, or jeopardize his honor for any reason? That he married for love, not for… emoluments in exchange for stud services?

“Win, I’m bored.” The admission felt both pathetic and brave.