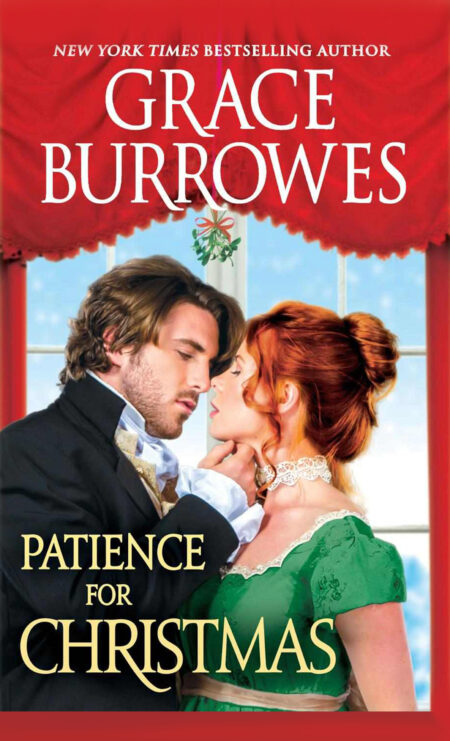

Patience for Christmas

Patience for Christmas is the story of advice columnist Patience Friendly, whose relationship with her stubborn, over-bearing, publisher, Dougal MacHugh, is anything but cordial. Dougal challenges Patience to take on a rival columnist in a holiday advice-a-thon, and sparks fly clear up to the mistletoe hanging from every rafter. Will Patience follow the practical guidance of her head, or the passionate advice of her heart?

Enjoy An Excerpt

“Professor Pennypacker is wise, kind, cheerful, and witty. Why shouldn’t I loathe him?” Patience’s Friendly’s honest question met with smirks from her dearest friends in all the world, though she’d spoken the plain, seasonally inappropriate truth.

“You don’t loathe the professor,” Elizabeth Windham said. “You have a genteel difference of opinion with him from time to time, such as educated people occasionally do. More tea?”

Patience paid regular visits to the four Windham sisters because they were excellent company, though their lavish tea tray figured prominently in her affections as well.

“Half a cup, and then I must be going.”

Elizabeth obliged, her idea of a half portion coming nearly to the cup’s brim.

“It’s the first Monday of the month. Does Dreadful Dougal demand your time, again?” Charlotte Windham asked around a mouthful of stollen.

“Mr. MacHugh is my publisher. I ought not call him that.” In her thoughts, Patience called him much worse. “He might be lacking in polish, but Dougal P. MacHugh ensures my little scribblings find their way into many hands.”

Dougal referred to Patience’s advice columns as little scribblings, but the coin her writing earned was not so little to a spinster without means.

“Your advice to that boy who bashed his sister’s dolly was lovely,” Megan Windham said. Unlike her sisters, she wasn’t embroidering (Elizabeth), knitting (Anwen), or devouring tea cakes (Charlotte). Megan had a quiet about her that soothed, though Patience suspected that quiet also hid a lively imagination.

All four sisters shared Patience’s red hair, but they were from a ducal family. If they’d gone swimming in the Serpentine, it would have become the latest rage. Their red hair made them striking, while Patience’s earned her frequent admonitions from her publisher to control her temper.

“I’ll take you up with me in the carriage,” Anwen said. “I’m to read to the boys this afternoon, and one wants to be punctual when setting an example for children.”

“You’re passionate about the orphanage,” Patience said. “I wish Dread—Mr. MacHugh permitted me to write about the plight of poor children in winter, instead of limiting me to an advice column.”

Nothing, nothing in all of creation, compared to the pleasure of a good, strong cup of black tea on a cold December day, unless it was the same cup of tea shared with friends. Without the company of these four young women, Patience would likely have been reduced to rash acts.

Marriage to the curate, for example.

As Anwen put away her knitting and Charlotte wrapped up the stollen—most of the loaf for the orphans, but two slices for Patience—snow flurries danced outside the parlor window. A brisk breeze pushed them in all directions, and the gray sky threatened a proper snowfall.

Mr. MacHugh would call it a braw, bonnie day, but he was Scottish, and his view of life paid litte heed to tea cakes, cozy parlors, or mornings spent with friends. He was all business all the time, the opposite of the company Patience treasured most dearly.

“You’ll come by a week from Wednesday to see how we’re progressing with our holiday baking, won’t you?” Elizabeth asked as Patience accepted her cloak and scarf from the Windham butler. “We still use your mama’s recipe for lemon cake.”

A woman who lived alone didn’t bother with the expense of holiday baking. “I’ll see you a week from Wednesday, same as usual, and I’ll try to get Mr. MacHugh to do a piece on Anwen’s urchins. If people won’t contribute to charity at Yuletide, then we’ve become a hopeless species, indeed.”

The prospect of persuading Mr. MacHugh to do an article on Anwen’s favorite orphanage was daunting, and as Patience bundled into the Windham coach beside Anwen, a predictable melancholy settled over her, as heavy and familiar as the woolen lap robe.

How many more years would pass in this same pattern? Writing at all hours, battling with Dougal MacHugh over the content of the columns, envying friends their holiday luxuries, and hoping the winter was mild?

The problem wasn’t entirely poverty. Many families with little means found joy in one another’s company, looked forward to brighter tomorrows, and celebrated the holidays cheerfully.

The problem was Patience’s life, and no advice columnist in the realm—not even her kindly, wise, dratted competitor, Professor Pennypacker—could tell her how to repair an existence that felt as bleak and barren as the winter sky.

![]()

“I have never met a female more inappropriately named than Patience Friendly,” Dougal MacHugh muttered. “If I ask her to meet me on the hour, she’s fifteen minutes early, and if our meeting requires an hour of her time, she’s pacing my office thirty minutes on. Send her in.”

“Shall I put the kettle on, Dougal?”

Harry MacHugh was a good lad, but he was a cousin—most of Dougal’s employees were cousins of some sort—and thus he presumed from time to time where prudent men would not.

“She’ll not take tea with me, Harry. Ours is a business relationship.” A lucrative one too. But for that signal fact, Patience would doubtless have ejected Dougal from her life as briskly as she dispatched her readers’ problems.

“Even business associates can share a cup in honor of the season,” Harry said. “I’ll just—”

“You’ll just show the lady in, and then dash off a note to your mum and da. It’s Monday.”

“Aye, Dougal.”

Oh, the martyrdom a fifteen-year-old could put into two words and a heavy sigh. Over the past year, as Harry had shot up several inches in height, his penmanship had improved, as had his vocabulary and grammar. Dougal had the boy review the ledgers too, and purposely made the occasional error to test Harry’s skill with figures.

Harry clomped out of Dougal’s office as the clock on the mantel struck a quarter till the hour. Miss Patience Un-Friendly whisked through the open door a moment later.

Once a month, Dougal endured the disruption of her presence in his office. Discontent accompanied her everywhere, a discontent she channeled into repairing the lives of readers without the sense to solve their own problems—bless their troubled hearts. Even the rhythm of her footfalls—rapid, percussive, confident—spoke of a woman determined on her own ends.

And the damned female had the audacity to be lovely. She wasn’t simply pretty—pretty was for daffodils and landscapes—she was… all wrong.

A woman dispensing advice as the practical, blunt Mrs. Horner ought not to have a full mouth made for kisses and smiles. She ought not to have features that begged for the understated grace of porcelain angels, and she had no business having a figure that made Dougal think of cozy Highland winters and a wee dram shared before bed.

He’d hoisted a rare wee dram to Miss Friendly’s curves, and many more to the blazing intelligence and nimble pen attached to them.

“Miss Friendly, good day. Perhaps your watch is running a bit fast.”

“Mr. MacHugh, greetings.” She pulled off her gloves and tossed them onto the mantel. “Sooner begun is sooner done. Shall we get to work?”

She usually remarked on how much Harry was growing, and how fat the office cat—King George—had become.

“Are you in a hurry, madam? We can reschedule this meeting if you’d like, but I’ve a special project to discuss with you.”

“No time like the present, Mr. MacHugh. Let’s be about it.” She took her customary seat at Dougal’s worktable, a battered, scarred article that had been in the MacHugh family since Robert the Bruce had been in nappies.

“Shall I build up the fire, Miss Friendly?”

“Why would you do that? Coal is dear, Mr. MacHugh, as you well know.”

From her twitchy movements and the bleak quality in her gaze, Dougal knew something was bothering her—more than the usual weight of the world she carried on behalf of her readers. The daft woman took her job seriously, considering her replies to each letter as if the fate of entire neighborhoods might rest on whether she could solve the reader’s dilemma.

Dougal added half a scoop of coal to the fire in the hearth. “You’re still wearing your cloak. I thought you might be cold.”

She shot to her feet and plucked at the buttons marching down the front of her cape. “You’re absolutely right. How silly of me. My mind is on this month’s stack of letters, and—”

Miss Friendly fell silent, her expression disgruntled as she fussed with the fastenings at her throat. In the clerk’s office, she would have had a mirror to aid her, but Dougal had no need to examine his own features.

“Allow me,” he said, brushing her hands aside. She’d knotted the strings more tightly rather than loosening the bow, and Dougal took a small eternity to get her free. In those moments, Miss Friendly stared over his shoulder as if he were a physician taking medically necessary liberties, while Dougal tormented himself with stolen impressions.

She smelled of damp wool, for the day had turned snowy, but also of lemons and spice. Clove, cinnamon, he wasn’t sure what all went into her fragrance, but it put him in mind of Christmas cakes, cloved oranges, and blazing Yule logs.

The backs of his fingers brushed against her skin, which was surprisingly warm, given the inclement weather. Also soft. For a moment, her pulse beat against his knuckles, and then the strings came free.

“There ye go.” His burr showed up at the worst moments, when he was angry or tense.

Or drunk.

“My thanks.” Miss Friendly stepped away to draw the cloak from her own shoulders. She hung it over a coat rack near the door and started fishing in the pockets.

Her hems were damp, and her boots were likely soaked. Dougal discreetly moved her chair closer to the fire and waited for the lady to take her seat.

“Are you looking for something?” he asked when she’d searched both pockets thoroughly.

“I’ve misplaced my glasses, or forgotten them. Without them—”

“Use mine,” he said, plucking the spectacles from his nose. “You’ll be able to see halfway to the Highlands with them.”

Her gaze went from the eyeglasses in his hand—plain gold wire and a bit of curved glass—to his face, back to the glasses.

“I couldn’t take your spectacles, Mr. MacHugh.”

Because he’d worn them on his person? “We’ll get nothing done if you can’t see the letters to read them. I have a spare pair.”

He retrieved the second pair from his desk and donned them, though the earpieces were a trifle snug and the magnification wasn’t as great.

“So you do. Well.” Miss Friendly was practical, if nothing else. She put the glasses on and took her seat. “Let’s get to it. The holidays bring all manner of problems, and I’m sure I can offer some useful advice in at least a few instances.”

“You’ll have to do better than that,” Dougal said, settling into the chair across from her.

Always across from her, for two reasons. First, so he could torment himself with the sight of her, sorting and considering, losing herself in her work; and second, so no accidental brush of hands, arms, or shoulders occurred.

“I do not care for your tone, Mr. MacHugh,” she said, taking off the spectacles and polishing them on her sleeve. “I always do my best for my readers. If you imply something to the contrary, we shall have words.”

“I’m a-tremble with dread, Miss Friendly,” he said, passing her a wrinkled handkerchief. He loved having words with her. She hurled words like thunderbolts, didn’t give an inch, and was very often right—and proud of it.

“What is this?” she asked, peering at the embroidery in the corner. “Is this a unicorn?”

“Wreathed in thistles. My cousins Edana and Rhona MacHugh do them for me. Winters are long in Perthshire, and Edana and Rhona like to stay busy.”

Eddie and Ronnie had a small business, about which their brothers probably knew nothing. They and the ladies of their Perthshire parish embroidered various Scottish themes on handkerchiefs, gloves, bonnet ribbons and so forth, and shipped them to Dougal. He distributed the merchandise to London shops and fetched much higher prices for the goods than the women could have earned in Scotland.

“It’s quite pretty,” Miss Friendly said, passing the handkerchief back. “More of a lady’s article than a gentleman’s though, don’t you think?”

“Perhaps, but it reminds me of home and family, and fashion is hardly foremost in my mind.”

“One could surmise as much.” She gave him a perusal that said his plain attire was not among the problems she was motivated to solve, then picked up the first letter in the stack.

This was Dougal’s favorite part of the meeting, when he could simply watch Patience at work. She read each letter, word for word, considered each person’s problems and woes as if they were her own, then listed and discarded various possible solutions to the challenge at hand. By the time she left, she’d have a month’s worth of worries put at ease, a month’s worth of difficulties made manageable for some poor souls she’d never meet.

“We’ll have to work quickly today,” Dougal said before she’d reached the end of the first letter.

“Because of the weather?”

The snow was coming down in earnest now, though it could easily let up in the next five minutes.

“Because I’ve got wind of a scheme Pennypacker’s publisher has devised to take advantage of the holidays. You said it yourself: The holidays bring problems, and old Pennypacker isn’t about to leave his readers without solutions.”

“It’s unchristian of me, but I dislike that man.”

“No, you do not.” Dougal hoped she did not or the poor professor was doomed to a very bad end.

“The professor takes issue with my advice at least once a month, and directs people into the most inane situations. Why he’s become so popular is beyond me, though I’ll grant you, the man can write.”

Ever fair, that was Miss Friendly. “He can make you a good deal of coin too.” Dougal rose to retrieve a ledger from the blotter. “These are your circulation figures from last November and from this November.”

She studied the numbers, which Dougal had checked three times. “We’re doing better. We’re doing… appreciably better.”

That news ought to have earned Dougal a smile at least, but the lady looked puzzled. “I’m not doing anything differently,” she said. “Mrs. Horner’s Corner dispenses kindly, commonsense advice and responds to reader pleas for assistance with domestic problems. What’s changed?”

Exactly the question a shrewd woman should ask. Dougal passed her another sheaf of figures.

“Take a look at August and then September. The numbers begin to climb, and the trend continues into October and then last month. The increase isn’t great between any two months, but the direction is encouraging.”

The rims of Dougal’s spectacles glinted in the firelight as Miss Friendly ran a slender, ink-stained finger down a column of figures. The picture she made was intelligent, studious, and damnably adorable.

“That man, that dreadful awful man,” she murmured, setting the papers aside. “Pennypacker began writing his column in August. You think the readers are comparing my advice to his?”

“I’m nearly certain of it,” Dougal said. “All too often, Pennypacker deals with at least one situation that’s remarkably similar to the ones you choose, and his advice is often contrary to your own. In the next column, you’ll elaborate on your previous suggestions, annihilate his maunderings, and further explicate your own wisdom. He returns similar fire, and in a few weeks, we have a bare-knuckle match over the proper method for quieting a querulous child at Sunday services.”

“Gracious, I’m a pugilist in the arena of domestic common sense.”

Now she smiled. Now she beamed at the flames dancing in the hearth as if Dougal had handed her the Freedom of the City and a pair of fur-lined boots.

“Pugilists have to defend their titles, Miss Friendly, and if we let this opportunity slip by us, the crown will go to Pennypacker.”

She glowered over the spectacles. “He’s a posing, prosy, pontificating man, Mr. MacHugh. Why on earth his opinions of household management should signify, I do not know. The professor has likely never changed a baby’s clout or kneaded a loaf of bread, if he’s even a professor.”

Had the prim Miss Friendly ever tended a baby? Did she long for a baby of her own, or even a family complete with adoring husband? Self-preservation suggested Dougal ask that question at another time.

“You might think gender alone disqualifies Pennypacker from having anything useful to say,” Dougal replied, removing his spare glasses before they gave him a headache. “But his publisher intends to let him natter on for twelve consecutive days as we lead up to Christmas. Yuletide special editions, the publisher’s holiday gift to the masses, though the gift won’t be free.”

Miss Friendly drew off the spectacles and covered her face with her hands. The gesture was weary, but when she dropped her hands, sat back, and squared her shoulders, the light of battle shone in her blue eyes.

“Twelve consecutive days? That means answering dozens of letters.”

“Sundays off, I’m assuming, but yes. At least three dozen letters answered in less than two weeks. I know it’s a challenge when your friends will be expecting you to socialize and exchange calls.”

Her shoulders slumped. “They will. It’s baking season. Drat.”

When Dougal had opened his publishing house three years ago, he’d faced enormous odds. London had a thriving, highly competitive publishing industry with each house specializing in certain products—herbals, sermons, animal husbandry, memoirs, and so forth. A readership took time to develop, and Dougal’s inheritance was all he’d had to sink into his business.

He’d teetered on the brink of ruin until Patience Friendly had shown up in his office, full of ideas, pen at the ready.

Mrs. Horner’s Corner had rescued an entire publishing house—women were avid readers, it turned out—and when Dougal had moved her column to the top of the front page, the entire business had found solid footing. He was on his way to becoming the domestic advice publisher, and Patience Friendly was his flagship author.

Dougal could not afford—literally—to either coddle her or earn her disfavor. “I know the timing is poor,” he said. “I’m sure you don’t want to spend your holidays ignoring friends and family—but this is an opportunity. If we don’t step into the ring with the professor now, we’ll lose ground when we could take ownership of it. You have the better advice, and the ladies who buy my paper know it.”

“My readers are very astute,” she said, worrying a nail. Her readers, not the customers, not the readers. Hers. “And they depend on me. Do you know, my laundress discusses my column with my housekeeper, and they both say that at the baker’s, the ladies talk of little else.”

Yes, Dougal knew, because he frequented taverns, coffee shops, booksellers, churchyards, street corners, all in an effort to aim his business where the public’s interest was most likely to travel.

Dougal kept his peace. Twelve special broadsheet editions in fourteen days was an enormous undertaking, but he was determined that his business thrive, and that Miss Patience Friendly thrive too.

He owed this woman.

And he always paid his debts.

![]()

Heavenly choruses, a dozen columns in two weeks!

The part of Patience that loved to be of use, to write, to feel a sense of having made a contribution leaped at the prospect. The part of her who’d had enough of Professor Pontifical was ready to answer every letter in Mr. MacHugh’s stack.

But other parts of her…

Across the table, Dougal MacHugh waited. He was deucedly good at waiting, arguing, persisting—at anything necessary to further his business interests. Patience admitted to grudging admiration for his tenacity, because at one time MacHugh’s determination to build a business had been all that stood between her and a life in service, or worse, dependence on a spouse.

She didn’t like his tenacity though. Didn’t like much of anything about him, though he had a rather impressive nose.

He’d taken off his spare glasses, and thus good looks entirely wasted on a Scottish publisher were more evident. Untidy dark hair gave him a tousled look that made Patience want to put him to rights.

He’d probably bite off her hand if she attempted to straighten his hair.

His eyes were a lovely emerald color, fringed with unfairly thick lashes, and his mouth—Patience had no business noticing a man’s mouth. Anybody would notice Mr. MacHugh’s broad shoulders though, and his height. He was a fine specimen, which mattered not at all, and a finer businessman.

That mattered a great deal.

“You think we can do this, Mr. MacHugh? Put out twelve special editions in two weeks?”

His regard was steady. Patience liked to think of it as a man-to-man gaze, because not even her dear friends regarded her as directly.

“I think you can do this, Miss Friendly.”

Did Mr. MacHugh but know it, his confidence in her was worth more than all of the pence and quid he paid her—and he did pay her, to the penny and on time.

“My compensation will have to reflect the effort involved.”

“Madam, if this goes well, your compensation will result in a very fine Christmas for some years to come.”

Patience longed to pick up the next letter and lose herself in the worries and quandaries of her readers, but she’d yet to agree to take on Mr. MacHugh’s project.

“What do you mean, a very fine Christmas for some years to come?”

He came around to her side of the table, bringing pencil and paper with him. He moved with an economy of motion that Patience associated with cats and wolves, not that she’d ever seen a wolf.

Mr. MacHugh took the chair beside her. “Look at the numbers, Miss Friendly.”

Who would have thought a publisher would smell of apples and pine? That scent distracted Patience as Mr. MacHugh explained about the printer’s pricing scheme, the potential market for broadsheets in London, the publishing houses that had recently closed, and the magnitude of the opportunity awaiting Mrs. Horner’s Corner.

“So the professor has chosen an excellent time to cast a wider net,” Mr. MacHugh concluded. “I’d suspect him of being a Scotsman, his maneuver is so exquisitely timed.”

Patience picked up the page, half covered with numbers and tallies. Impressive tallies. “Not all keen minds are Scottish, sir.”

Patience wasn’t feeling very keen. Her earnings had crept up, true, but she’d used the monthly windfall to pay off debts and set aside a bit for leaner times. What would it be like to know she had enough when those lean times came around?

For they inevitably did.

“You hesitate to spoil your holiday season with too big an assignment.” Mr. MacHugh stuck his pencil behind his ear. “I can’t blame you for that, it being baking season and all.”

He lowered his lashes in a manner intended to make Patience shriek, his tone implying that crumpets would of course hold a woman’s attention more readily than coin.

“Without a steady income, Mr. MacHugh, there can be no crumpets. My concern is that the work you put before me must meet the standard I’ve set over the past two years. Perhaps the professor can churn out his drivel at a great rate, but my efforts are more thoughtful.”

“Your efforts are very thoughtful.”

Mr. MacHugh knew how to deliver a compliment that was part contradiction, part goad. Rather than toss his own spectacles at him—they were fine eyeglasses—Patience got up to pace.

“Christmas falls on a Saturday this year,” she said. “If we’re to publish twelve editions, the last on Christmas Eve, that means—”

“The first edition should come out this Saturday, December eleventh. The twelfth and the nineteenth being the Sabbath, that means—”

“This Saturday! That means we go to the printer’s four days from now.”

“Aye. Glad to see your command of the calendar is the equal of your ability with words. Can you do it?”

Could she give up the baking, the buying last-minute tokens for Elizabeth, Charlotte, Megan, and Anwen? Hustle past the glee clubs singing in the holidays on London’s street corners when she longed to linger and bask in the music? Give up sitting quietly at church just to hear the choir rehearse the holiday services?

Oddly enough, she could. Putting aside holiday folderol for two weeks to secure a nest egg was the practical choice.

“You hesitate,” Mr. MacHugh said, tossing his pencil onto the table. “This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to build Mrs. Horner’s Corner into an institution, and you hesitate. What are you afraid of, Miss Friendly?”

Of all Dougal MacHugh’s objectionable qualities, his perceptivity ranked at the top of the list. Were he not also unflinchingly, inconveniently, relentlessly honest, Patience could not have endured his acuity.

When her writing was weak, he told her. When the solution she proposed to a problem was poorly thought out, he told her. When she was repeating herself, preaching, making light of a problem, or otherwise missing the mark, he told her.

And worst of all, when he was wrong—a maddeningly infrequent occurrence—he admitted it.

Patience took her seat beside him, where the fire threw out the most warmth. “What if I can’t do this?”

“Failure is always a possibility, but we minimize it with planning and hard work.”

“You haven’t left me any time to plan.”

“Opportunity looks like inconvenience to the indolent.”

She wanted to stick her tongue out at him. “Must you be so Scottish?”

“I am Scottish.”

“You needn’t make it sound as if that’s the most wonderful status a man could boast of. Back to the matter at hand, if you please. If I attempt this twelve-edition madness and fail, it’s worse than if I’d let the professor bore everybody for two weeks straight. The readers will say I’ve exceeded my limits and overtaxed my dim female brain.”

“Your brain, while admittedly female, is anything but dim. Think like a general. What do you need for your campaign to succeed?”

Generals were not female… except some of them were. Patience had learned from the same tutors hired to instruct her brother—Papa had seen no reason to also pay governesses—and throughout history, some generals had been female.

There were female deities, female saints, and female monarchs. All the best tribulations in mythology had been female too. The Medusa, the sirens, the furies.

“I’ll need help,” she said. “I’ll need immediate editorial reviews, somebody to run errands for me, and… crumpets. Lots and lots of crumpets.”

She’d surprised him. How Patience loved that she’d surprised the canny, competent, Scottish Mr. MacHugh.

“There’s a bakery on the corner for your crumpets. Detwiler will be happy to edit material as you complete it, and I will be your personal errand boy. Shall we begin?”

Gracious warbling cherubim. Patience knew the bakery well—she walked past it every time she dropped off her columns. Mr. Detwiler was as fast as he was competent, but as for that other item…

Apparently, Mr. MacHugh could surprise her too.

“We begin now, and your first assignment as my errand boy is to fetch me a batch of crumpets.”

End of Excerpt

Patience for Christmas is available in the following formats:

Hachette

December 18, 2018

- Barnes & Noble Nook

- Kobo

- Apple Books

- Amazon Kindle

Digital:

Print:

Sorry, no print version available!

- Kobo UK

- Amazon Kindle UK