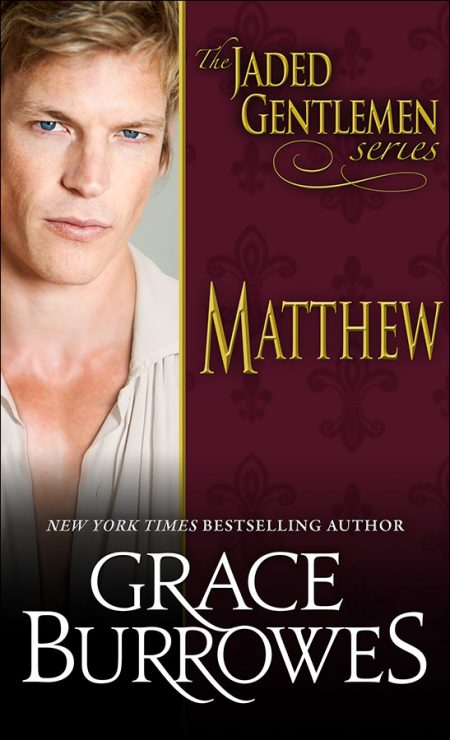

Matthew

Book 2 in the Jaded Gentlemen series

Theresa Jennings strayed from propriety as a younger woman, though now she’ll do anything to secure her child’s future among decent society. She’ll even make peace with the titled brother who turned his back on her years ago.

Matthew Belmont, local magistrate and neighbor to Theresa’s brother, is a widower who’s been lonely too long. He sees in Theresa a woman paying a high a price for mistakes long past, and a lady given far too little respect for turning her life around. Theresa is enthralled by Matthew’s combination of honorable intentions and honest passion, but then trouble comes calling, and it’s clear somebody intends to ruin Theresa and Matthew’s chance at a happily ever after.

Enjoy An Excerpt

Chapter One

In Matthew Belmont’s world, a damsel in distress took precedence over an early morning inspection of the pear orchard, particularly when the damsel weighed close to a ton and had a foal at her side.

“I wouldn’t ask it of you this early in the day,” Beckman Haddonfield said, as one of Matthew’s stable lads took Beck’s sweaty gelding to be walked out. “But if we lose the dam, we could well lose the foal, and neither Jamie nor I can figure out what ails the mare.”

“Best saddle Minerva,” Matthew called to the groom. “You, Beckman, will wait a few moments before joining me at Linden. Your horse needs to catch his wind, as do you.”

A father of three learned to speak in imperatives, though unlike Matthew’s sons, Beckman would probably heed the proffered direction.

Minerva heeded Matthew’s direction—most of the time. She was a game grey mare, approaching twenty, but spry and flighty. On a brisk autumn morning, she made short work of the trip to Linden, negotiating cross-country terrain like the seasoned campaigner she was, though she over-jumped a rivulet for form’s sake.

Matthew was soon handing her reins over to old Jamie, the Linden head stable lad. “Who is our patient?”

“It’s Penny,” Jamie replied, loosening Minerva’s girth. “The autumn grass must be too rich, or maybe the filly’s upsetting her. Damned wee beast is at her mama all the time.”

The proper office of children was to upset their parents, something Jamie couldn’t know.

“The nights are getting cold, Jamie. The filly’s bound to nurse a lot.”

Jamie hobbled beside Matthew into the barn, Minerva clip-clopping along behind them.

“I know racehorses,” Jamie said, “and I manage with the hunters, hacks, and carriage horses, but a colicky brood mare flummoxes me.”

Females of any species flummoxed Matthew, and he thanked the Almighty regularly that his children were all boys.

“I’m none too fond of colic myself,” Matthew said. “Is Penny in the foaling stall?”

“She is, and the filly is in the next stall over. Miss Theresa Jennings is keeping an eye on ’em both.”

Miss Jennings would be a sister to Linden’s owner, Thomas Jennings, Baron Sutcliffe. In the excitement of the baron’s recent wedding, Matthew had not troubled his host for an introduction to Miss Jennings. Sutcliffe and his bride were off on their wedding journey, and thus nobody was on hand in the stables to make the introductions.

Needs must when valuable livestock was imperiled. Matthew moved down the barn aisle to the foaling stalls, where a tall brunette stood outside a half door.

“Miss Jennings, Matthew Belmont, at your service.”

She brushed a glance over him, her blue eyes full of anxiety. “Mr. Belmont, my thanks for coming. I know little of doctoring horses, but Penny is special to my brother, and Jamie said—”

The mare switched her tail, as if to say the idle chat could wait until later.

“Jamie was right,” Matthew replied. “Sutcliffe would happily look in on a mare at Belmont House in my absence. I’m pleased to do the same for my neighbors.” Often at a less convenient hour than this, and to a less pulchritudinous reception.

Miss Jennings was long out of the schoolroom and into the years when a woman’s true beauty shone forth.

The massive copper-colored equine known as Penny had pricked her ears at the sound of Matthew’s voice, while the “little” filly—easily three hundred pounds of baby horse—in the next stall over danced in circles.

“Are you comfortable with horses, Miss Jennings?”

“Reasonably. I know which end does what.”

The same starting point from which Matthew had embarked on his parental challenges.

“I’d like to bring the filly into her mama’s stall, though somebody should hold her while I look Penny over. I can wait for Jamie to finish with Minerva if you’d rather.”

“That won’t be necessary. I’ve held horses on many occasions.”

“The little one’s name is Treasure,” Matthew said, opening the door to the smaller stall. “The Linden stable master halter-trained the filly before he left for London.”

Matthew slipped the headstall over the filly’s ears, scratching at her fuzzy neck as he did. He kept up a patter of nonsense talk, telling the foal how fetching she looked in her halter, and how cozy she’d be in her woolly winter coat.

Matthew passed Miss Jennings the lead rope and preceded her from the stall.

“And now,” he said in the same conversational tones, “we’ll step over to Mama’s stall, so we might—”

The instant Matthew slid the half door back, the filly shot forward, yanking Miss Jennings with her. The lady wisely dropped the lead rope as she stumbled, and Matthew found himself smack up against a lithe, warm human female, one whose lemony scent blended with the earthier aromas of horse and hay.

In the next instant, Matthew tramped on Treasure’s lead rope, though the filly had slipped through the narrow opening to her mama’s stall and was nuzzling the mare with obvious relief.

The instant after that became both awkward and… interesting. As Miss Jennings struggled to find her balance, and Matthew struggled to know where to put his hands. “I beg your pardon, Miss Jennings.” Matthew’s grip closed on the lady’s upper arms. “Are you all right?”

Stupid question, when the lady was gasping for breath. She’d been flung at Matthew with enough force to knock the wind out of her.

“Relax, madam.” Matthew probably ought not to have ordered her to relax. “You’ll get your breath back if you give yourself a moment. The fault was entirely mine. I should have known the filly would be frantic. I should have kept hold of that lead rope, and I do apologize—”

Miss Jennings held up a hand, then gestured at the mare and filly. “If the mother’s ill, should the filly be doing that?”

The foal was nursing, her little tail whisking gleefully about her quarters.

Matthew removed his hands from Miss Jennings’s person. “I expect she’s hungry. I tend to forget my manners when I’m peckish. Then too, a determined female of any species should be not underestimated.”

For the foal, who’d never been separated from her mama to speak of, nursing would be both physical and emotional sustenance. Matthew did not share that indelicate observation as he approached the mare. He talked nonsense again, a patter of flattery and small talk intended to let the mare know exactly where he was at all times.

“Now sweetheart,” Matthew crooned, “you won’t give me trouble if I merely want to admire your smile, will you?” He gently pried up the big mare’s lips and pressed on her gums. “There’s a love, now let’s have a listen, shall we?”

He ran a hand down the horse’s shoulder and pressed an ear to her side, all the while letting the filly nurse.

“You must tell me, Penny, if something is amiss.” He switched sides and listened again to her gut, though that required maneuvering the filly about. “I expect you miss your Wee Nick, don’t you, hmm? You have the look of a female pining for her favorite.”

Miss Jennings flicked a wisp of hay from her sleeve. “Penny seems calmer with you in her stall. When Jamie tried to get close to her, she pawed and circled in the straw.”

“Making the proverbial mare’s nest.” Matthew moved to the horse’s shoulder. “Let me have a look at your legs, my girl.” He ran his hands up and down each sturdy front limb, Penny having been bred to the plough. “No heat, no swelling, no bumps, no sore joints… You’re being coy, Penny, my love.”

The mare turned a limpid eye on him, as if to confirm his accusation.

“Is she eating?” he asked as he started on the back legs.

“Like the proverbial horse. The stable master wrote out the rations for each horse, and Penny gets as much as any other two horses put together.”

A parent’s lot was arduous, regardless of the species, particularly a lactating parent.

“Have you those written instructions on hand?” Matthew asked as he pressed on the mare’s spine, vertebra by vertebra. “She’s may have a bit of indigestion, but it isn’t colic. Her limbs are sound. Eyes, ears, teeth, and mouth are all in fine shape. She’s producing milk, she’s not noticeably dehydrated, and mastitis doesn’t seem to be the issue.”

“Mastitis?”

“Inflammation of the…” Well, hell. Matthew waved a hand in the general direction of his chest. “Of the… udder. If the mare is sore, she won’t let the filly nurse, so she gets impacted in addition to the underlying inflammation—it’s quite painful for the horse. Happens more often in cows,” he went on, wishing his idiot country squire mouth would shut itself.

“Cows, Mr. Belmont?”

Had the lady taken a step back?

“I beg your pardon.” Matthew avoided the consternation in Miss Jennings’s gaze by scratching Penny’s hairy withers. “A rustic life familiarizes one with animal husbandry.”

Rural surrounds did not, however, require that one bleat on in the presence of a lady as if one were a sheep stuck halfway over a style.

“I’ll find the stable master’s instructions.” Miss Jennings passed Matthew the foal’s lead rope and nearly ran down the barn aisle.

Matthew leaned his forehead against the horse’s neck.

“God help me.” At thirty-five years of age, he was turning into that pathetic caricature, a bumpkin who cared for naught but his hounds and horses, a man without conversation or sophistication of any sort. An embarrassment.

At least he was an embarrassment who took the care of his land and livestock seriously. Matthew toed through the straw, and his boot came in contact with the inevitable horse droppings.

Miss Jennings reappeared at the door to the stall, a piece of foolscap in her hand. “I have Nick’s list.”

“What proclamations did Wee Nick make for his Penny?” Matthew crossed the stall to peer down at the paper. “This is quite detailed. I would need my spectacles to decipher the handwriting. Would you mind reading it for me?”

The damned dim light was the trouble, and too many late nights attempting to make sense of legal tomes or his sons’ handwriting.

“That’s no bother at all, Mr. Belmont.”

Miss Jennings stood right next to Matthew and scanned the written instructions. This gave him his first opportunity to focus on Miss Jennings, to inventory her features and assess her attire.

Matthew enjoyed most of his job as magistrate because the post involved solving the little mysteries that passed for criminal mischief in the wilds of Sussex. Who let Mrs. Golightly’s heifer out, and who might have stolen three of Mr. Dimwitty’s handkerchiefs from Mrs. Dimwitty’s clothesline?

Theresa Jennings struck Matthew as a puzzle with missing pieces. Something about the woman was off, like a column of even numbers adding to an odd total. She was tall, brunette, blue-eyed, and wearing a dress nondescript enough to be appropriate in the stable, but still something….

“The stable master is a man given to detail, isn’t he?” she concluded after rattling off a list portions and a schedule of activities.

“Nicholas loves this mare,” Matthew replied. “Risked his life for her when the old stable burned, and suffered injury himself while rescuing her.” But then, Nicholas Haddonfield was partial to females on general principles. “Does he write anything more?”

Matthew told himself to move, to leave the mare and foal in peace, but here he was, lounging shamelessly against the stall door, appearing to read over Miss Jennings’s shoulder when in fact he was imbibing the lemony scent of her hair and admiring the swell of her bosom against her modest brown walking dress.

Matthew’s yearning for closeness with Miss Jennings wasn’t even sexual—not very sexual, anyway—which was vaguely alarming. He simply longed for the softness and sweetness of a woman.

“Nicholas says Penny isn’t keen on ice in her bucket, particularly when the first hard frosts come through.” Miss Jennings squinted at the paper, which gratified Matthew exceedingly. “She prefers carrots to apples.”

“Fussy old thing.” Matthew stepped over to the horse and scratched her great ears before the temptation to smooth his palm over Miss Jennings’s shoulder overcame his manners.

“That’s probably what’s troubling you, isn’t it?” Matthew asked the horse. “You don’t have your personal body servant on hand to see to your every whim and pleasure, and your morning tea isn’t brewed exactly to your liking.”

The horse reciprocated Matthew’s sympathy by wiggling her lips against his hair, a gesture he tolerated from one fussy old thing to another. He and Minerva had the same sort of relationship, and it was not eccentric.

Despite what his sons might think.

“I’ll have a word with Jamie and with Beckman,” Matthew said as he closed the stall door. “The mare needs the chill taken off her water in the morning. She’ll drink more, and her belly will ease as a result.”

“Of course.”

Miss Jennings eyed Matthew assessingly, looking something like her brother. She and the baron shared a particular curve of the lips, a quirk of the mouth when thinking. While Matthew tried again to figure out what about Miss Jennings didn’t quite sit right, she ran her fingers over his hair.

“The mare destroyed your coiffure, and I don’t suppose a cowlick”—she repeated the gesture several times—“would comport with your manly dignity. There.”

Matthew’s own wife had never… his own children… if he’d permitted a valet to dress him, he wouldn’t have allowed… He blinked down at Miss Jennings, resisting mightily the urge to investigate the state of his hair with his fingers.

“I’m sorry.” She took a step back. “I didn’t mean to presume, but Thomas has always been particular about his turn-out, and men can take their appearance quite…”

Matthew offered Miss Jennings the smile his sons referred to as the harmless old squire smile, which served nicely for inspiring confessions from miscreants under the age of ten.

“No matter, Miss Jennings. I haven’t been properly fussed over by anybody in a very long time. You’re… sweet to trouble over me.”

Odd—exceedingly odd—but sweet. Matthew left Miss Jennings by the brood mare’s stall and went off to find Jamie, intent on lecturing the head groom about the proper preparation of her ladyship’s morning tea.

![]()

Squire Belmont sauntered away, moving like a man at ease in a stable, at ease in his life. The look in the big mare’s eye when she’d spied him had been nothing short of adoring.

If a horse could have said, “Thank God you’ve come,” the mare would have been that horse. She’d wiggled her big lips across Mr. Belmont’s blond hair as if he were her favorite fellow of any species.

And the squire hadn’t taken the least umbrage.

He’d easily sorted out Penny’s problem, suggesting he was a man of discernment, but what man of discernment would have called Theresa Jennings sweet?

Jamie came bustling out of the saddle room. “You’ll feed the lad, won’t ye?”

“Feed whom?”

Jamie jerked his chin in Mr. Belmont’s direction. “Yon squire. He’s notorious good at appreciating his victuals, and his cook done took off for Brighton again. Least you can do, being neighbors and all. So what’s ailing our Penny?”

Thomas had the most impertinent help—a divine irony, considering how prickly Thomas could be—though every person at Linden worked hard.

“I believe Mr. Belmont is searching you out to discuss what ails the mare,” Theresa said. “He suggested she was missing the stable master.”

“Never thought of that. Might could be. Mares are particular. Squire!”

Jamie trotted off, amazingly spry when he wanted to be, and flagged down Mr. Belmont, who stood in the stable yard conferring with Beckman.

When Theresa joined them a few moments later, she had the sense she was interrupting a religious service.

Jamie pushed something Theresa did not examine too closely about in the dirt with the toe of a dusty boot.

“You say she’s not drinking enough, Squire?”

“Exactly, which means she isn’t producing a lot at one time for Treasure,” Mr. Belmont went on, “so the filly is at her, and the mare is cranky and out of sorts, and probably getting a tad corked up as a result.”

Theresa was not an equestrienne, but she knew enough not to ask what corked—what that term—meant.

Beckman cleared his throat and cast a desperate glance at the squire.

“Beg pardon, Miss Jennings.” Mr. Belmont nodded at her, though Theresa had the sense the squire barely noticed her. “So what the mare needs is a little more attention to the temperature of her morning water bucket, and she should come right in a day or two.” He swung his attention to Beckman. “Some extra coddling from you wouldn’t go amiss either, because you most closely resemble Wee Nick.”

“In miniature,” Jamie chortled.

“The stable master is that grand a fellow?” Theresa interjected. Beckman was every bit as tall as the squire and as muscular as regular stable work could make a man. Beckman’s hair was a lighter blond, his eyes a lighter blue. He was, in short, a less weathered, less honed version of the squire.

Beckman’s smile held a touch of pride. “My older brother is that grand in many respects.”

“Pride goeth,” the squire muttered, though he smiled. “You’ll keep me informed?”

Jamie winked. “Bet on it.”

Mr. Belmont pulled gloves from his pocket. “Then my contribution here is complete. A word with you, Miss Jennings?”

He offered his arm, a quaint gesture under the circumstances. Thomas offered Theresa his arm, and she tolerated it because he was her brother. Brothers could be old-fashioned where sisters were concerned—even sisters who had fallen so very far from grace.

Maybe, especially those sisters.

“You are preoccupied,” the squire observed as he walked with her across the drive to a bench under a spreading oak.

“Thinking of my brother.”

“Baron Sutcliffe is a capital fellow, and he has found a lovely bride, one well worth his notice.”

Mr. Belmont could not know how talk of happy nuptials still had the power to wound Theresa. The dart of pain came as a small surprise to her too.

“You know Miss—her ladyship, Mr. Belmont?”

“I’ve known Loris for almost ten years. Shall we sit?”

“Of course.” Theresa had forgotten the strictures of ladies and gentlemen in company with each other. She hadn’t considered herself a lady for years, nor had she enjoyed the company of a true gentleman since well before that.

Mr. Belmont was a gentleman, even if he did air his veterinary vocabulary with astonishing capability.

Theresa’s escort seemed in no hurry to resume the conversation, and she was content to sit beside him. Matthew Belmont was at ease in proximity to her, and simply being close to him was soothing.

That shouldn’t be—he was an adult male—but there it was.

“I proposed to Loris at one point,” Mr. Belmont said, smoothing out the wrinkled fingers of his riding gloves against his thigh. “She turned me down, for which I suppose I should be grateful.”

A breeze stirred the remaining oak leaves, a dry, sad sound. “Grateful to be rejected, Mr. Belmont?”

“I wasn’t asking for the right reasons, and my proposal flattered neither of us.”

A failed proposal could not possibly be what Mr. Belmont had wanted to discuss, and any woman with sense would have changed the subject.

Theresa had not visited with a neighbor for years, though, much less a male neighbor. “What are the right reasons?”

“There are many right reasons.” Mr. Belmont sat back, stretched an arm over the back of the bench, and crossed long legs at the ankle.

The topic was not unnerving him. Maybe nothing unnerved him.

“What’s most important,” he went on, “is to be honest about what one’s reasons are. I married out of familial obligation, duty, and, for want of a better term, youthful eagerness—my late wife was very pretty. She married me out of social necessity and gratitude. We understood one other’s reasons, and the union functioned adequately as a result.”

What did this have to do with an ailing mare? And yet, Theresa was curious, for Mr. Belmont’s adequate union sounded… lonely.

“Were you happy?”

“We grew to be content,” he replied, as if reciting a catechism. “We were happy raising our children.”

“Content. A consummation devoutly to be wished.”

Mr. Belmont brightened, like a hound who hears a rustling in a nearby thicket. “You enjoy Shakespeare, Miss Jennings? My oldest went on a Shakespeare spree two summers ago. He nigh drove his brothers to swear eternal illiteracy.”

Safer ground, this—much safer. “I like to read, Shakespeare among others. And you?”

“Living in the country, one acquires an aptitude for either reading or drinking. I have the Bard’s complete works in my library, if you’re due for an infusion.”

He’d regret that offer, though Theresa wouldn’t presume on his books in any case.

“You give me leave to raid your library, while I invite you to join me in a figurative raid on the larder. Penny would insist I offer you a meal for your trouble.” As would Thomas, oddly enough.

Mr. Belmont rose and drew Theresa to her feet, then placed her hand on his arm.

“I’m utterly harmless, Miss Jennings, in all settings save one. Put me before a hearty meal, and my focus narrows as if I were Wellington advancing across the Peninsula. No larder is safe when I’m in the neighborhood.”

He gave her the same smile he’d offered her in the barn. Charming, friendly, and as deceptive as Priscilla when reporting last night’s bedtime.

Theresa walked with him through the Sutcliffe gardens, which were fading as gardens did when autumn had supplanted summer. The chrysanthemums were putting on a good show, and heartsease was enjoying the cooler weather, but winter was edging closer, and the flowers knew it.

Mr. Belmont made small talk, and yet, Theresa was not fooled.

Any man who could diagnose something as obscure as a mare’s persnickety preferences regarding her water bucket, any man who inspired even the mute beasts to watch him walk away, any man who called Theresa Jennings sweet and made her wish it was so, was not a harmless man.

![]()

Breakfast passed pleasantly, much to Theresa’s surprise. The squire had the gift of conversation, and he was acquainted with every soul for twenty miles in any direction, as well as their dogs, horses, ailments, and legal complaints.

And yet, as he recounted anecdotes or judicial contretemps, he never named names, or sermonized about his neighbors’ foibles. If anything, he viewed life from a tolerant perspective Theresa hadn’t encountered for too long.

“When you are both neighbor and magistrate,” he said, “people will tell you of any and every mishap, spat, or peculiar circumstance, most of which has no bearing on anything, save a need to talk.”

Despite his ability to converse amiably, he also paid assiduous homage to the offerings on the sideboard.

“How did you become magistrate?” Such a fate typically befell an older fellow.

“My late neighbor, Squire Pettigrew, was prepared to bear the dubious honor for at least another twenty years, but he was the victim of food poisoning, and I was the next likely choice because my father had held the post prior to Pettigrew’s tenure. The job has been interesting, if occasionally inconvenient.”

For Matthew Belmont “occasionally inconvenient” was doubtless the equivalent of protracted cursing from another man.

“To sit in judgment of one’s neighbors,” Theresa replied, “without becoming arrogant would be a challenge.” For Thomas, that challenge would have been considerable, at least the Thomas whom Theresa had known ten years ago.

“Arrogant?” Mr. Belmont peered at his plate, from which every morsel of eggs, toast, ham, bacon, and stewed apples had been consumed. “Holding parlor sessions is often a humbling business, because one can so easily be in error.”

“But who is to know that? People usually come to their own conclusions, and the truth has little to do with it.” Theresa kept the bitterness from her words, barely, but the squire wasn’t deceived.

She liked him a little less for his perceptivity, and respected him more.

“You have been tried, judged, and executed in the court of public opinion, I’d guess. Not a pleasant experience.” Mr. Belmont shared his evidentiary conclusion gently.

Worse yet, his blue eyes were kind.

Theresa pushed her eggs about on her plate. “You however, have likely never endured such an experience.” Nobody should have to endure public censure, however silent or subtle it might be.

Mr. Belmont moved the teapot closer to her wrist—the good porcelain, suggesting the kitchen was on its best behavior.

“There, madam, you would be wrong, and I notice you do not gainsay my conclusion. Do you intend to eat those eggs?”

He’d put away a prodigious amount of food, but for all his leanness, he was a good-sized fellow.

“You’re welcome to them, if that’s what you’re asking.”

He reached for her plate. “I realize I am risking quite the bad impression, but my cook has run off to Brighton—she’s always running off somewhere now that my sons reside in Oxfordshire. Your cook, on the other hand, has a fine hand with the omelet, and an empty stomach has no pride.”

Theresa sat, nonplussed and charmed, as her guest scraped her untouched food onto his plate.

“I haven’t seen a man demolish a meal like this since Thomas lived at Sutcliffe,” she said. “He grew so quickly and was always active. Food disappeared whenever he was around, just plain disappeared.”

Thomas had had no pride then. He’d been all appetite—for food, for knowledge, for books, languages, and life.

“I share the same ability,” Mr. Belmont said between bites, “to make food disappear. While my sons’ handling of a plate of food defies description. Gustatory legerdemain is the closest I can come. Food vanishes. Fortunately, your cook is aware of my tendencies and provides portions in abundance when I’m on the property.”

“So when were you pilloried by the local gossips?” Theresa asked.

He frowned at the eggs on his fork. “Any man serving as magistrate comes in for a deal of criticism. He charges those whom public opinion would forgive, he does not charge someone who is unpopular. Evidence matters naught when the yeomen gather around their pints, and in some cases, I am not free to disclose the entire basis upon which I make my decisions.”

The eggs, which had to be cold by now, met their fate, while Theresa remained quiet in hopes Mr. Belmont would continue his recitation.

“It’s a d— deuced thankless job,” he went on, “and that’s before we consider what the judges at the assizes have to say about one’s work, or the vicar judging from his pulpit each Sunday while he exhorts the rest of us to judge not. Then too, Mr. Burton Louis fancies himself the local equivalent of Dr. Johnson because he manages to print a broadsheet of purest blather each—”

Mr. Belmont put his fork down. “I am whining. Forgive me.”

The charming smile was nowhere in sight, and yet, Theresa liked this version of Squire Belmont—a little testy, running low on neighborly good cheer, not too proud to eat cold eggs.

What a shame they’d never have a chance to further their acquaintance. She ignored her heart’s plea for just a few more minutes of friendly, adult company with Mr. Belmont, and instead let the truth loose between them.

“You may assume, Mr. Belmont, that the mother of an articulate eight-year-old has overlooked whining far more protracted than your little lapse.”

Mr. Belmont stilled, as if he’d heard a sword drawn from its scabbard in the next room. His eyes were the predictable blue of the Englishman descended from Saxon ancestors, and Theresa braced herself to see his gaze grow chilly, or worse—speculating.

The corners of those eyes crinkled, and his expression became, if anything, commiserating.

“You’ll miss that whining someday, I assure you. You’ll miss the mud on your carpets, the slamming of doors above stairs, the inability of the child to recall where—in the space of two minutes—gloves, boots, books, or common sense has got off to. Would you like more tea, Miss Jennings? I’m after the last of the toast and want to wash it down properly.”

What Theresa wanted, was to ask if Mr. Belmont had heard her. Miss Theresa Jennings had an eight-year-old daughter. A man who prided himself on his animal husbandry needn’t any clearer clue to his hostess’s unsavory past.

Mr. Belmont’s hand was on the teapot, his expression hinting at both humor and regret. The service was decorated with a shepherd boy and a goose girl casting coy glances among twining flowers and gilt vines.

Mr. Belmont’s index finger bore a scar, a slash of white across an otherwise elegant, if unfashionably tan hand.

The sight of that scar—small, old, unremarkable, but suggestive of a story—provoked a peculiar insight: Theresa and the magistrate had in common the joys and frustrations of parenting.

The same reality that had ruined Theresa’s good name once and for all, gave her common ground with the king’s man. The sense of connection was so unexpected and rare, she might have turned up sentimental over it, if she hadn’t sworn off that useless proclivity years ago.

“You really do take your nutrition seriously,” she said, or maybe Mr. Belmont really did know how to change the subject. “If you’re still hungry, we have apple tart on the sideboard. Shall we enjoy it on the terrace with a fresh pot of tea? The southern side of the house is protected from the breezes and lovely at this time of the morning.”

“A wonderful suggestion.” Mr. Belmont rose and assisted Theresa to her feet, another quaint, disconcerting display. “Will I ever meet this whining prodigy who calls you mother?”

He missed his children badly. Thomas had said something about them visiting cousins or going up to university.

Theresa pondered the conversational options all the way to the terrace, where she decided on the only course she’d ever been able to tolerate where Priscilla was concerned: honesty.

“I am not in the habit of socializing with neighbors, Mr. Belmont. My life at Sutcliffe Keep was nigh monastic, and I preferred it that way.”

Mr. Belmont plucked a sprig of lavender from the border edging the flagstones, despite the blooms being well past their best season.

“Sutcliffe Keep is along the sea, isn’t it?” he asked, twirling the lavender beneath his nose. “The seacoast has always struck me as lonely.”

Matthew Belmont was not a stupid man, and yet, Theresa needed to be very clear with him regarding her situation.

“The sea wasn’t what isolated us, Mr. Belmont.”

Her comment was an invitation for her guest to recall a pressing engagement, bow politely, and take away his full stomach, kind eyes, and feeble attempt at whining by the simple expedient of striding off through the gardens.

“You have me at a loss, Miss Jennings.” His gaze was steady, his expression giving away nothing—not dread of another prickly subject, not avaricious anticipation of juicy gossip. He spun the lavender idly between his fingers, not a hint of tension in even that small gesture.

He was not outstandingly handsome, but he was attractive. This realization evoked sorrow—Theresa had not found a man attractive in years—and justified a ruthless display of common sense.

“My daughter is a bastard,” Theresa said. “I would not want to cause you or her embarrassment should the facts of her birth be revealed to you in her hearing.”

Mr. Belmont stood at Theresa’s side, while a pair of sparrows flitted among the nearby oaks, and a frisky breeze fluttered leaves donning their autumn glory. He didn’t clear his throat, didn’t narrow his eyes, didn’t quirk an eyebrow in invitation as other supposed gentlemen had many times before him.

“For your daughter,” he said, tucking the lavender into his jacket pocket, “I am sorry. Some will treat her unfairly on the basis of her circumstances, and for you…”

“For me?” Theresa prompted, ready to snatch up her skirts and whirl back to the safety of the house.

“I am sorry as well. Your trust was quite obviously betrayed. Fortunately, I conclude you treasure your daughter and she, you, and that is what matters most. Somebody did mention apple tart, if I recall. Shall we?”

He offered Theresa his arm again.

Shall we?

Two unremarkable, cordial words that swept aside judgment—and worse—dispensed with the prurient interest that often followed disclosure of Priscilla’s bastardy. Shall we?

Theresa laid her hand on his arm. His bare fingers closed over hers with a little pat, and he escorted her down the steps to the lower terrace.

Chapter Two

Mr. Belmont did the male version of prattling on as they walked, about tutors, about nannies, about how his two oldest sons had taken to their studies at university, about being unable to part with any of the ponies his sons had outgrown—ponies whose acquaintance Miss Priscilla might like to make.

His neighborly baritone filled a quiet morning, and filled an emptiness inside Theresa too. As a much younger woman, she’d had glimpses of what Matthew Belmont represented: decent society. He was kindness itself, civility, fair play, and all the classical virtues in a winsome package.

She should have met such a man ten years ago, though even ten years ago would have been too late, and even Matthew Belmont’s quiet gentlemanliness wouldn’t have affected the decisions she’d made then.

For Theresa, Mr. Belmont would have been—as he still was—too little and much, much too late.

They ate large servings of apple tart, and Mr. Belmont accepted a second helping without even a pretense of polite demurral.

A woman could enjoy feeding such a man, planning menus to delight him and to appease that prodigious appetite. She would look forward to sharing meals with him, and to simply being in his company.

“I’m off to finish my correspondence and balance ledgers that have been glaring at me for the past week,” Mr. Belmont said. “I enjoy the physical labor of harvest, but it generates a great deal of paperwork as well, and that, I confess, I find tedious.”

“I love the ledgers and balance sheets and figuring,” Theresa said, accepting his proffered arm with an ease that she would ponder when she had the solitude to do so. “At Sutcliffe, I did not trust the stewards and land agents to operate in Thomas’s best interests, so I supervised their every transaction.”

“They were not honest?”

“They were far from honest.” Weasels had more honor than that pack of vermin. “I pensioned off as many as I could before our grandfather died, and did the bookwork myself thereafter.”

“And where was our Thomas while you were busily defending the family seat?” Mr. Belmont asked. “He doesn’t strike me as a man who would allow his dependents to be taken advantage of.”

Theresa would also be honest with Mr. Belmont about this, in part because he’d whined a little and in part because nobody—not one person in Theresa’s hearing—had ever wondered why the wealthy Thomas Jennings, now Baron Sutcliffe, kept his sister moldering away at the family seat.

“Thomas and I had a significant falling-out before Priscilla was born. Despite every probability to the contrary, he did not expect to come into the title—didn’t want it, didn’t aspire to it, didn’t even acknowledge it at first—so the business of the estate was of no moment to him until about two years ago.”

The words were truthful, the way the visible portion of an iceberg could not be called a misrepresentation.

“I understood his succession was recent. Your family, like all families, apparently has its share of challenges.”

Challenges, yes, and Theresa was perishing sick of them.

“I looked after Sutcliffe, because from a young age, I understood that Thomas would likely become its owner someday. Shall I send some food home with you, Mr. Belmont? I cannot abide the thought of you going hungry while we have such abundance here.”

“I would not starve, but I might be tempted to accept an invitation from one of the marriage-minded mamas in the district. A man shold consider a bread-and-water diet before yielding to such folly.”

Thank goodness he was leaving. The longer Theresa was in Mr. Belmont’s company, the more she liked him.

“You will not remarry?”

“If I remarry, it won’t be to some girl half my age who thinks only to satisfy the dictates of her parents.”

His blue eyes were positively glacial as he voiced that sentiment, the sternness of his expression making him impressive in a different, intriguing way. He was the king’s man, prosecutor and judge when the situation called for it.

Though he was also a lonely papa.

“Mr. Belmont, I do believe that is the closest sentiment to irritation I have heard in your voice since meeting you.” The closest emotion to anger.

He’d been leading Theresa around the house, so they now stood at the bottom of the front steps, Theresa’s hand on his arm, his hand over hers.

“The ambushes started at Matilda’s very wake, if you must know. Neighbors typically provide meals for the aggrieved, and I swear I met more single young women over ham casseroles than I knew lived in all of Sussex. At the time, I was too upset to notice, and thank goodness my brother Axel shielded me from the worst of it, but the campaign didn’t stop there and hasn’t really stopped since.”

He seemed to realize he’d trapped Theresa’s hand on his sleeve and unlaced their arms with a sort of bow, then fished his riding gloves out of his coat pocket.

His tirade—for Mr. Belmont that surely qualified as a tirade?—merited a response.

“One wonders if widows endure the same sort of pursuit.” The pursuit Theresa had endured had been so much less genteel.

“The wealthy ones do, and they expect me to commiserate and even provide—”

Theresa could imagine what the local widows wanted from the tall, cordial squire. Their pigs probably went missing regularly—or their earbobs or their wits—as a result of what they sought from Matthew Belmont.

He fell silent while trying to button his second glove.

Theresa took his hand, glove and all, between her two and did up the button with the dispatch of a mother experienced at buttoning moving targets.

Though Mr. Belmont held absolutely still. “Thank you,” he said when Theresa turned loose of him.

“I have fussed at you twice in one day.”

“And I still find it sweet—wonderfully sweet—but what was that look about?”

He wanted more honesty from her, and what was the harm in one more little truth between them?

“I never grasped that men might feel as pestered as women do by unwanted attentions. Women can flounce off in high dudgeon, be insulted, plead a headache, or set the fellow down, but a gentleman…”

“Does so at his peril,” Mr. Belmont finished. “One doesn’t want to hurt the feelings of the sweet young things, but their mamas are quite another matter. For a time, I dreaded the churchyard after services and even procrastinated opening my mail.”

“Let’s go around to the kitchen, sir. I cannot bear the thought of what enduring more ham casseroles might drive you to.”

![]()

By the time they reached the kitchen, Matthew had figured out what bothered him about Theresa Jennings. The insight had come to him when the lady had buttoned up his right glove. She’d stepped closer, scenting the moment with lemon verbena and taking his hand in both of hers with a confident grasp.

For a succession of instants, he’d stared at the nape of her neck, at the curve of her jaw, at the way the morning breeze tried to wreak havoc with her dark hair—and failed. In profile, her features revealed the sort of classic proportions that gave her face a quality of repose and agelessness.

She was a beautiful woman and determined to hide it.

She did nothing—not one thing—to call attention to her feminine attributes. Her attire was not noticeably plain, it was un-noticeably plain. Her hair was swept back in a pretty, utterly unremarkable bun. She wore no jewelry. Her rare smiles bore no hint of flirtation, her gestures were contained.

Theresa Jennings hid in plain sight, and as Matthew studied the flawless, downy skin of her nape, he wondered if she hid even from herself. She was a spinster masquerading as a fallen woman, and the combination bothered him.

He wondered when a man had last pressed his grateful, hungry lips to that skin and made her sigh with passion?

Then he wondered if he—the sober, mature widower, the fellow hostesses prevailed upon to make up the numbers at the last minute—had misplaced his wits.

“The kitchen is always quiet this time of day,” Miss Jennings said, taking a wicker container down from a high shelf.

Matthew was too busy cadging a peek at her ankles to assist her. She bustled about, putting together a hamper of provisions in no time. A fresh loaf of bread, a mold of butter, some hard cheese, shiny red apples, cold sliced beef, grapes, and a half a loaf of spice cake all disappeared into the hamper.

“I cannot imagine this will hold you even until sundown, Mr. Belmont.”

“I will survive. The vicar’s oldest daughters do temporary duty for the evening meal, and we make do otherwise. You are most generous.” Also more competent in the big kitchen than a baron’s sister should be.

Her gaze inventoried the shelves like a general reviewing her troops. “You watched me cut that cake as if you were a starving raptor. What are you doing for dinner tomorrow night?”

A cold tray in the library, ledgers, a ham casserole of boredom, solitude, and duty.

“Imposing on you?”

Miss Jennings’s smile became one hint worth of wicked. “If you can bear Priscilla’s company, you are cordially invited to join us. It’s time to work on her company manners, and you’ve raised children. I feel certain you’re up to the challenge.”

A child at table was a splendid idea. Such company would preserve Matthew from lunatic speculations about napes and sighs and the taste of lemons.

“I didn’t simply raise children, Miss Jennings, I raised boys, that species of primate who finds rude noises produced with the body to be a form of entertainment, particularly before guests.”

She passed him a surprisingly heavy hamper. “My brother and my cousins weren’t like that. Even Grandpapa had his limits.”

“I’d forgotten Thomas had cousins.” Much less that Thomas had been raised with them by a titled grandfather. “He hasn’t mentioned them.”

“They are… deceased,” she said, opening the back door. “I shall walk you down to the stable.”

“I would enjoy that.” Matthew also enjoyed offering her his arm, and enjoyed even more when she took it—and then refrained from leaning, pressing, stumbling, or otherwise drawing his notice to her attributes.

Lovely though those attributes were.

“You are such a gentleman, Mr. Belmont.” Alas, this did not sound like a compliment. “I hardly know what to do with you.”

“Are you complaining?”

“I’m lamenting,” she replied softly, as they passed blown roses and withered salvia.

While Matthew, with a full hamper in hand and an invitation to dinner tucked beside the spice cake, grappled instead with an odd sense of rejoicing.

![]()

“Mama looked very nice,” Priscilla said as Miss Alice tied a perfect pink bow to the end of Priscilla’s right braid. Governesses could do that—tie bows that matched exactly—but Mama had the knack of leaving a bit of ribbon trailing on each side, which looked more grown-up.

“We will all present quite nicely,” Miss Alice said, finishing the second bow. “Do you have any questions, Priscilla? We didn’t have much company at Sutcliffe Keep.”

They hadn’t had any company, and not because Priscilla had been too young to leave the nursery. Even though she’d eaten nearly every supper with Miss Alice and Mama, she was still too young for company, according to Miss Alice.

That meant tonight’s meal with Squire Belmont was a Very Special Occasion.

“We practiced at breakfast and luncheon,” Priscilla said. “I’m not to speak unless a grown-up asks me a question, and I’m not to kick my chair. I am to be a pattern card of good manners and charm.”

Uncle Thomas had charm, and he could be silly, greeting Priscilla in a different language each time he saw her.

“I might have overstated the objective a trifle.” Miss Alice leaned closer to the folding mirror on the vanity and used her little finger to smooth the hair at her temple.

Miss Alice was pretty. She had dark hair, a nice voice, and she was smart. She was also Mama’s only friend.

“You look fetching, Miss Alice.”

Miss Alice would say that was forward of Priscilla, but Miss Alice was always going on about honesty being the first requirement of virtue—virtue had a lot of requirements—and Miss Alice had never, ever told Priscilla a lie.

“Thank you, Priscilla. We will give your mother and Mr. Belmont a few more minutes, then join them in the parlor. Are you nervous?”

Priscilla was supposed to say yes, but Miss Alice was the one who was nervous.

“Maybe a little. Mama said Mr. Belmont is a papa and that he’s nice. I won’t kick my chair even once, Miss Alice.”

Not quite a lie. Priscilla had learned to weave truth carefully, because sometimes, a girl needed to choose in which direction to be honest.

Priscilla wasn’t nervous, she was excited, for Mama’s brown dress was the same one she’d worn to Uncle Thomas and Aunt Loris’s wedding, the very best dress Mama owned.

Miss Alice checked the watch pinned to her bodice. “Five more minutes. I intend to be very proud of you by bedtime, Priscilla.”

Priscilla was proud of Mama. Yesterday, from a vantage point in the hay mow, Priscilla had watched as Mama had stood guard over Penny and Treasure, and then had helped Mr. Belmont figure out what ailed Penny.

Mama had been normal with Mr. Belmont. She had stood right next to him to read about Penny’s hay and feed, and she’d barely fussed when Treasure had knocked her right against Mr. Belmont.

Mama was a prodigious good fusser, sometimes.

Mr. Belmont had been normal with Mama too. He hadn’t sniffed and scowled and acted like Mama had embarrassed him by burping at the table or using bad language on Sunday.

Then, according to Cook, Mr. Belmont and Mama had had breakfast together. Mama never had company for breakfast, not even Mr. Finbottom, the curate who came around twice a year to collect for the Widows and Orphans Fund.

Mr. Belmont was ever so much nicer than Mr. Finbottom, and Mr. Belmont had come cantering up the drive on a white horse.

“What are you thinking about, Priscilla?” Miss Alice asked, giving her chignon a final pat.

“I’m thinking about my storybooks. If I am very good, may I read a whole story tonight?”

Miss Alice checked her watch again. She wore no other jewelry, ever, but her dresses were as fine as Mama’s, and her boots were newer.

“Company dinners can take longer,” Miss Alice said. “If we’re not too late in the dining room, then you may read one entire story of not more than twenty pages.”

Priscilla mentally inventoried her stories and came up with half a dozen short enough to qualify.

“I will be better than I’ve ever been before. Is it five minutes yet?”

Miss Alice’s mouth twitched, which meant she was trying not to smile. “Approximately five minutes,” she said, holding out a hand to Priscilla.

Priscilla let herself be led to the steps at a pace so ladylike, her ninth birthday would probably arrive before they got down to dinner, but she was determined to be very, very good, so she didn’t complain.

“I’m nervous,” Miss Alice said at the top of the steps. “I suspect your mama is too, Priscilla. We mustn’t muck this up.”

“We’ll be pattern cards of good manners and charm, Miss Alice. Don’t worry.”

A girl learned to manage on her own when she had nearly a whole castle to herself. Mr. Belmont was nice—Penny wouldn’t like him if he was a rotter—and thus nobody should be worried.

Priscilla would, however, be as well-mannered as she knew how to be, for in every one of her stories, one fact remained reliable: The fellow who rode the white horse was the one to rescue the princess. Mr. Belmont rode a lovely white mare, had the golden hair required of all self-respecting princes, and he had got himself invited to dinner with Mama and Miss Alice.

All that was needed was a magic spell or two, and nobody would have to go back to that miserable, cold, damp castle by the sea ever again.

![]()

“Mr. Matthew Belmont,” Harry, the senior footman announced, stepping back to admit Matthew to the Linden library. “Shall I tell the kitchen our guest has arrived, ma’am?”

“Thank you, yes, Harry.” Miss Jennings rose, and in evening dress her efforts at camouflage were significantly less successful. Her gown, while several years out-of-date, was a chocolate-brown velvet that flattered her hair, her eyes, and her figure—most especially her figure.

“Miss Jennings.” Matthew bowed over her hand. “How lovely you look. I would not have thought to attire you in that shade, but it is most becoming.”

She appeared pleased by his compliment, also flustered, like a lady who’d left the schoolroom not many years past, rather than the mother of a precocious eight-year-old.

“I am always relieved when the cooler weather appears and I can get out my velvets. You are a splendid sight yourself, sir.”

Splendid? Well. Matthew was abruptly glad he’d bothered with a sapphire stick pin, gold watch fob, and matching sleeve buttons, though finding the entire set had taken him nearly half an hour.

“I have little call for proper evening attire anymore, but the clothing still fits, and the company is well worth the effort.” Laying it on a bit thick, old boy.

“May I offer you a drink, Mr. Belmont?”

God, yes. Yesterday, the idea of an evening meal in Miss Jennings’s company had seemed like a fine notion, particularly in the opinion of that vast cavern known as Matthew’s belly. Tonight, he had stared at himself in his dressing mirror and realized he was… nervous, to be sharing a meal with a woman whose company he enjoyed.

“A tot of brandy wouldn’t go amiss.”

“Brandy it will be.” Miss Jennings poured a hospitable portion from the decanter on the sideboard.

“I know some ladies are reluctant to take strong spirits,” Matthew said, “but we’re likely to get frost tonight. Shall you have a nip to keep the chill off?”

Matilda had sworn by regular medicinal nips. Miss Jennings looked far less taken with the notion.

“Perhaps a drop,” she said, pouring not much more than that into a glass. “Shall we be seated? We have a few minutes before Priscilla shatters the king’s peace in the name of showing off her manners.”

Matthew took a seat on the sofa and tried to ignore the sense that he’d mis-stepped somehow regarding the spirits. Miss Jennings hadn’t struck him as a high stickler, but perhaps he ought to have asked for a glass of wine?

She settled herself in a rocking chair at right angles to the fire, her drink untouched in her hand.

“Were you raised here in Sussex, Mr. Belmont?”

Onward to the small talk, then. “We were, my brother and I.” He and Axel had endured childhoods in Sussex, at any rate. “I grew up at Belmont House, and my parents are buried there. I suppose I will be too.”

“One hopes not for quite some time.”

Matthew took a cautious sip of his drink. “Sometimes I feel as if I’ve already been interred.” His admission was uncharacteristically morose, and personal—honest, too—but Miss Jennings continued to rock serenely.

“I feel the same way about Sutcliffe Keep. I should love it, because I’m raising my daughter there, where my father was raised. But for so many years, I’ve looked at Sutcliffe as a resource I had to protect for my brother, as an obligation. Priscilla says the castle doesn’t look like a place where people live. It looks like a place where armies fight with spears and boiling oil. She’s right.”

“From the mouths of babes.” Though thank God that Matthew’s sons didn’t feel that way about Belmont House. “If you dislike Sutcliffe Keep, why not leave?”

The rhythm Miss Jennings set up, rocking languidly before the fire, soothed as the brandy did not, excellent potation though it was.

“Why don’t you leave Belmont House? We set down roots, and there we are, whether the place we planted ourselves ten years ago is where we wish to be planted today or not.”

In other words, Miss Jennings had wanted to leave the ancestral pile by the sea, just as Matthew had often wanted to turn his back on Belmont House.

“I do leave,” Matthew said. “I go up to Town when my schedule allows. I visit my brother. I went to Oxford to fetch Christopher home between terms last year.”

Matthew had felt like a truant first former on every one of those excursions, vaguely anxious about livestock and servants who likely hadn’t spared him a thought.

Miss Jennings held her glass up to the firelight, as if she might read portents in the flames’ reflections.

“This trip to Linden is the first I’ve left Sutcliffe since Priscilla was born.”

Eight years in a place meant for spears and boiling oil? “You were rusticating with a vengeance.”

She set the drink down, again without taking a taste. “It’s only rusticating, Mr. Belmont, if one has another option. I was simply living my life.”

Miss Jennings did not bumble. She advanced through a conversation with the confidence of a French cavalry unit charging an English infantry square. Fearsome, unstoppable, all business at a steady, ground-eating trot that boded ill for Albion, and could break into an all-out gallop at any moment.

So Matthew met her charge with a volley of curiosity. “Would your brother have assisted you to find a more hospitable domicile if you asked him to?”

“My brother is a good man,” Miss Jennings replied, addressing the fire in the hearth more than her guest. “Thomas is also as stubborn as a lame mule, and when he left Sutcliffe after university, he was not in charity with me. We had enjoyed a lively correspondence, but after that, my letters were returned unopened until he came here to Linden.”

Baron Sutcliffe was stubborn, stubborn in the way of a man whose determination had saved his soul. Alas, the trait was apparently common to both siblings.

“To what do you attribute your brother’s change of heart?”

“The title, to some extent. Thomas has ever been responsible and as head of the family, he was responsible for me. Then too, his best friend—Viscount Fairly—married, and happily so. But it wasn’t only that….”

Harmless old squires heard many confessions, most of them not remotely criminal. Matthew wanted to hear this one, for Miss Jennings carried mystery about with her like a favorite shawl. He took a dilatory sip of a dangerously pleasant brew rather than interrupt her.

“Thomas didn’t know about Priscilla. She has helped tip the balance.”

Matthew and his hostess had passed from small talk to philosophy to confidences. Watching Miss Jennings rock quietly in her chair, her brandy untouched, her outdated gown flattering a figure Matthew could not quite ignore, he had the sense these exchanges were the least of the shadows Theresa Jennings carried in her heart.

Generally, Matthew kept the confidences imposed on him as a matter of responsibility—as a neighbor, as an exemplar of the king’s peace, as a gentleman.

Hetty Longacre’s youngest bore a strong resemblance not to the blue-eyed Mr. Longacre, but to Tobias Shirley, right down to the Shirley brown eyes. Even Matthew’s sons had remarked the likeness, which had given him many a bad moment.

The upright Frampton Jones, brewer of the finest ales in Sussex, went to London for mercury treatments.

The list of woes and secrets Matthew was privy to was endless, and like the horse hair that accumulated on his wardrobe by the end of some days, he ignored the lot. With Theresa Jennings, ignoring the shadows in her eyes would be unkind in the first place, and impossible in the second.

A woman who had the courage to reveal her heartaches on her own initiative, rather than as a matter of official investigation or neighborly inquisition, would not expect endless sunshine and small talk from those around her.

“I should not be telling you this, Mr. Belmont, and you likely hear enough useless chatter without my adding to your store.”

Of useless chatter, Matthew had a king’s ransom. His shelves were nearly bare of honest conversation, though.

“You should be telling someone, madam. How did Priscilla tip the balance between you and your brother?”

Matthew already had an inkling, because the children had tipped the balance between him and Matilda, for a time anyway.

“A child…” Miss Jennings looked away, out the mullioned windows to where nightfall wasn’t yet relieved by a rising moon. “A child reminds one of one’s own youth, and in Priscilla, Thomas was able to see parts of me that as a younger, angrier man, he could not acknowledge. I am his elder, but that doesn’t mean I was always an adult.”

Except in some sense, she had been an adult since birth. Matthew recognized the breed, for he saw it in the mirror and in his brother Axel. Christopher had an element of the same quality.

“Thomas loved his sister, when she wasn’t an adult,” Matthew said, “when she was a little girl with a big imagination and no friends. Isn’t it wondrous how children allow us to love?”

Miss Jennings rose and stood with her back to him. “Unfair, Mr. Belmont.” The rocker went on moving, slowing gradually.

“My apologies.” Matthew rose as well, and not because manners required it, and not entirely because he wanted to stand behind Miss Jennings breathing lemon verbena and studying the intricate braiding she’d woven in her hair.

“Forgive my presumption, madam, and allow me to point out, whatever the cause, you and your brother are reconciled, and into the bargain, Priscilla now has her Uncle Thomas, who I am sure will make up for the time lost as best he can.”

Miss Jennings nodded, but still didn’t turn, and Matthew resisted the urge to take her by the shoulders and make her face him, so that he might see her extraordinary blue eyes and the emotions they held. His gaze fell again on the nape of her neck, graceful, tender, and abruptly, quite… kissable.

If he wanted his face slapped.

“More brandy?” he asked, stepping over to the decanter, though the ploy was absurd. Miss Jennings hadn’t touched her drink.

She turned, her expression composed, her eyes painfully bright. “No thank you, though you must help yourself to as much as you like.”

“You were generous,”—he held up his unfinished drink—“and I am trying to demonstrate restraint by savoring such fine libation.”

A soft tap on the door heralded Harry’s reappearance.

“Dinner, Miss Jennings, and Miss Alice and Miss Priscilla are on their way down.”

“Priscilla’s governess usually joins us for the evening meal, unless Priscilla has been boisterous and Alice wants a break,” Miss Jennings said. “Ours was a very humble household.”

Household? At least Matthew’s prison had been commodious.

He offered his arm. “With three ladies to grace the table, I will be the most envied of men.”

“Reserve judgment on that. Your companions will be a child, a confirmed bluestocking, and me.”

Not a one of whom would be trying to inveigle Matthew into taking liberties or offering marriage.

“And your companion will be Squire Belmont, or as my boys christened me, Squire Bottomless. We shall make a delightful company, and your cook will be in alt.”

Chapter Three

Despite Mr. Belmont’s regalia and the unsettling conversation, dinner with Squire Bottomless would be informal, with both Alice and Priscilla on hand to ensure nothing untoward was said.

Nothing more untoward. Theresa had nearly come undone at what Mr. Belmont had deduced about her upbringing at Sutcliffe.

A little girl with a big imagination and no friends. What a recipe for misery that had become. As she allowed Mr. Belmont seat her, then watched him display the same courtesy to Alice and even Priscilla, Theresa reminded herself that her guest was dangerous.

He was attractive, with height, blond hair, blue, blue eyes, and a sense of contained, competent energy—a fine specimen, like a well-bred horse or a fit hound. If anything about him was bottomless, though, it was his calm spirit.

Matthew Belmont viewed life with a tolerance as startling as it was alluring. Others might take that broad-mindedness for granted, but Theresa wanted to probe its edges and origins.

Thank the kindly powers, Alice and Priscilla would prevent such folly.

Mr. Belmont turned to the child as the last course was served, and the topic of the Belmont pony herd had been discussed at length.

“What have you found most interesting here at Linden, Miss Priscilla?”

Priscilla’s brow puckered, which made her look more like her uncle. “Linden Hall is easy. If you want to go from your bedroom to the kitchen, you needn’t travel up two flights and down one, then cross the bailey to get there. Linden likes the light, it doesn’t huddle up in its stones like it’s always happier in the dark. Uncle Thomas has a stable, not just a few stalls under the gatehouse, and Aunt Loris has flowers and flowers and flowers.”

“Have you helped her make scents?” Mr. Belmont inquired.

He had excellent instincts with children. Alice acknowledged as much in the look she sent Theresa across the table.

Priscilla beamed at their guest. “I do help, and Aunt made a scent for me. Here.” She stuck out her arm and waved her wrist under Mr. Belmont’s nose.

He sniffed delicately at her wrist. “Lovely. Sunny, like daffodils, and you.”

“That’s what I asked for,” Priscilla replied. “Uncle Thomas likes it when Aunt Loris smells like biscuits, but we haven’t found scents yet for Mama and Miss Alice.”

“More complicated ladies need more complicated scents,” Mr. Belmont said—and with a straight face too. “Are you missing your Uncle Thomas?”

Theresa sat back and watched as an adult male held a conversation with her daughter. The experience was appallingly novel. Thomas teased the child and indulged in linguistic antics Priscilla found delightful. Viscount Fairly had joked and tickled and similarly entertained Priscilla, but neither man had engaged the girl’s mind.

“I miss Uncle lots,” Priscilla said. “I think that’s because I only just met him here at Linden. If he lived with us, I would probably miss him less. I want Mama to let us live here, but she keeps telling me not to pester her.”

Mr. Belmont’s expression remained respectfully attentive. “Pestering is hardly ever a good tactic with one’s mama. Surely you must find fault with some aspects of Linden?”

Alice stepped into the breach, for Priscilla could be an eloquent critic. “Perhaps you might consider your answer at your leisure, Priscilla?”

“I’ll think about it,” Priscilla said. “May I come see your ponies, Mr. Belmont?”

Mr. Belmont pretended to ponder the question. “That might come close to pestering, child.”

“Was I pestering, Mama?”

“More wheedling than pestering,” Theresa temporized. “You have done an excellent job with your studies since Uncle Thomas and Aunt Loris left for Sutcliffe Keep, and you’ve completed all your stories. If the squire is willing, we can schedule a visit.”

To see the ponies, which spared Theresa admitting she’d like to call upon the squire himself.

“Do you enjoy horses, Miss Portman?” Mr. Belmont inquired of Alice.

“From a safe distance. Upwind, if it can be arranged.”

“A town lady, then? One comfortable going all year without hearing the cows low or the roosters crow?”

“You have me.” When she smiled, Alice was quite pretty. Theresa had known the woman for nearly five years and was astonished to note this. “Unfortunately for Miss Priscilla, I am very good at devising ways of entertaining and educating that do not call for excursions beyond the house.”

“But Mama rescues me,” Priscilla interjected, “so I can go outside, and Miss Alice can have a break from me, because I am a handful.”

Grandpapa had called Theresa so much worse than that.

“And because you need to stretch your legs,” Theresa said, “as do I, from time to time. We would be pleased, Mr. Belmont, to come see your ponies. Now then, who would like some chocolate cake?”

Theresa had gone to trouble with this cake, making it herself that very afternoon. Life at Sutcliffe had been isolated, with the nearest market town seven hilly miles distant. If Theresa had wanted confections and fancy dishes, she’d learned—partly out of sheer boredom—to make them herself, and this sweet was among her favorites. The cake itself was rich, moist chocolate, the filling raspberry, and the lot was served with whipped cream.

The staff might have disapproved of her presuming on the kitchen, but they’d never declined a serving of cake.

The squire’s eyebrows rose as dessert was brought to the table. “My compliments to the cook, again. Appearance alone suggests this will be as delicious as all the preceding courses.”

They tucked into their cake, Mr. Belmont going silent, perhaps in the pursuit of alimentary bliss. When his portion had been consumed, he sat back. His smile was bashful, likely the reaction to the three pairs of female eyes watching him with amusement.

“I enjoyed the entire meal, Miss Jennings, but the company and your cake have to win top honors for the evening.”

Alice rose. “Some of the company must depart for their beds, and that includes you, Priscilla.”

Priscilla scrambled out of her seat and scampered over to Theresa, dark braids bouncing.

“Good night, Mama.” She wrapped her arms around Theresa’s neck and squeezed. “Will you tuck me in and hear my prayers?”

“Later, Priscilla.” Theresa kissed her daughter’s forehead. “You should be very proud of yourself. Your manners were lovely and your conversation gracious.”

“Am I growing up?” Priscilla asked, nose in the air.

All too quickly. “You are. You are becoming quite the young lady.”

Alice extended a hand. “Come along Priscilla, before you say something outrageous and your mother will have to revise her opinion.”

“Good night Mr. Belmont.” Priscilla trotted over to him and held out her arms.

Mr. Belmont, who had risen when Alice had stood, scooped the child up as naturally as if it were part of his evening ritual.

“Pleasant dreams, Princess.” He smiled through her fierce hug and bumped her cheek gently with his nose. “Don’t be in too big a hurry to grow up, and don’t forget that you promised me a story with a happy ending.”

“You shall have it soon,” Priscilla said as he deposited her on her feet.

“Genius cannot be hurried,” Mr. Belmont murmured, as the child led her governess from the room. “What an utter delight she is. Boys are such busy creatures and charming in their own way. A fellow can do things with his sons, show them how to go on, teach them all sorts of useful and arcane lore, but a little girl is such a lovable creature.”

“That one is.” Mr. Belmont’s observation invited Theresa to look beyond Priscilla’s table manners, penmanship, and diction, to the miracle of the growing child herself. “I am no end of relieved that Thomas has acknowledged her as his niece. She is much like him, busy, studious, imaginative, and she can mimic anyone so closely you’d think she’d trod the boards.”

Mr. Belmont resumed his seat and peered down the neck of a wine bottle still more than half full.

“You persisted in mending the breach with Thomas because of Priscilla and her right to know and be loved by her family.”

A hypothesis, for Matthew Belmont had that sort of mind. Curious, analytical, interested in others. Theresa had once been burdened with a lively curiosity too.

“Some of my persistence was on Priscilla’s behalf. Shall I ring for tea, or would you perhaps like another brandy to finish your meal?”

“What I would like is a turn in the garden with a congenial lady on my arm. The meal was by far the best I’ve had in months, but my digestion would benefit from some movement.”

“Fresh air appeals.” As did avoiding any more discussion of Theresa’s differences with Thomas. She and her brother were talking, true, but difficult words still needed to be said—eventually. She rose, as Mr. Belmont drew her chair back for her.

“I bet I can find you a sprig of lavender on the south terrace,” he said, “and we’ll be out of the evening breeze as well.”

“Priscilla is right about the flowers here,” Theresa replied, grateful for the change in topic. “The place is just short of overrun with them, particularly the steward’s cottage.”

“Loris likes her flowers and loves making scents,” Mr. Belmont said as they made their way through the library to the terrace beyond. “If Sutcliffe were so inclined, he could turn the flowers into a successful commercial venture.”

“Have you mentioned that to him?” Theresa asked, stepping out onto the flagstone terrace and leaving Mr. Belmont’s side to test the dampness of the soil in the pot of pansies on the table.

The pansies were thirsty, which Theresa would mention to Harry. She’d neglected to have the torches lit, though a full harvest moon was clearing the horizon to the east. Were she a different woman with a different past, she’d take a moment to consider the propriety of a moonlit stroll with an unmarried gentleman.

She’d lost the right to that hesitation long ago. Instead, she’d considered the bother to the servants of having to light a garden full of torches for a short constitutional on a chilly evening.

“I’ve mentioned my ideas regarding the flowers to Loris,” Mr. Belmont said. “The recipes and labor are largely hers. Tell me, Miss Jennings, have I given offense?”

Theresa stood on her side of the terrace, feeling awkward, because she’d no handkerchief with which to wipe her hand clean. “I beg your pardon, Mr. Belmont?”

“You disdain to take my arm,” he said, flourishing white linen in the darkness, “though I recall you allowing me the privilege of providing escort on previous occasions.”

He was smiling, teasing her, the handkerchief dangling from his hand like a slack flag of truce.

“I beg your pardon.” Theresa made use of the handkerchief, passed it back to him, and wrapped her hand around his elbow. “Now we might stumble around in the dark as one.”

“You are so wonderfully tart, madam. Like a bracing lemonade punch on a hot, dull day.”

“Food is very important to you, isn’t it? And yet I can’t liken you to any one single dish or drink.”

“Perhaps I am like that marvelous cake you served. Tall, sweet, and elegant.”

More teasing—Theresa had nearly forgot that adults could tease each other. “How can I trifle with your arrogance without insulting my dessert? Are you also perhaps sinfully rich, wickedly decadent?”

As soon as the words were out of her mouth, Theresa regretted them. They were the mindless banter of a sophisticate, a tease, a woman who might be trolling for custom, and who might not.

“Are you flirting with me?” He sounded hopeful. They had wound their way around the south side of the house to the gardens bordering the back lawns.

“I don’t mean to.” Theresa’s days of purposefully courting perdition were long past. “I do beg your pardon.”

She dropped his arm and walked off a few paces to settle on a worn wooden love seat. She realized the error of that decision when Mr. Belmont simply sat himself down beside her, and let a silence bloom between them.

“Here.” He shrugged out of his coat and wrapped it around her shoulders with a gentle brush of his hands down her arms. “The air is cooler than I had anticipated.”

“Mr. Belmont, you ought not,” Theresa began tiredly, but the warmth and spicy scent of him were seeping into her from his coat. To be the object of such consideration felt wretchedly lovely.

Also absolutely, shamefully wrong.

![]()

Matthew lounged back and crossed his ankles, prepared for Miss Jennings to finish a wonderful evening on a sour note.

“I believe you are working up to more of that tartness that I find so intriguing,” he said. “If you’re trying to offer a set-down, you’d best adopt another tactic.”

“I am out of practice,” she said. “You can tease and flirt and make pleasant conversation by the hour, and yet for me…. I’d forgotten what an effort it is.”

“You needn’t make an effort with me, Miss Jennings,” Matthew said when it became obvious she would say no more. “I am a simple man who appreciates his friends and the many blessings of his bucolic existence. I mean no offense with my remarks.”

“None taken.”

In that terse phrase, Matthew heard a world of resignation, loneliness, and weariness, emotions with which he had become all too familiar. On impulse, he took Miss Jennings’s hand in his, surprised at how cold her fingers were, and equally surprised that she let him. Emboldened by her acquiescence, he laid a careful arm around her shoulders, saying nothing, merely holding her against the heat of his body.

For a brief eternity, she was still, tacitly resisting, but then, on a soft sigh, she let her head rest on his shoulder and relaxed against him.

The moon rose higher, clearing the horizon and bathing the world in benevolent, silvery light.

This was what Matthew longed for. Not to tease, flirt, or banter, not to toss inane compliments at Miss Jennings, or match wits with her prickly nature and lively mind. He wanted simply to hold her, and watch the moon rise silently over the lovely autumn landscape.

![]()

By the time Theresa reached the sanctuary of the nursery, Priscilla was fast asleep.

“She’s exhausted from her great adventure,” Alice said, taking one of the rocking chairs by the hearth in the playroom. “She did very well at dinner, though Mr. Belmont is a treasure. Any girl would be on her best behavior around him.”

Theresa took the other rocker, for Alice’s interrogation would start any moment. “Not you too, Alice.” Alice was a treasure. Theresa had no idea how she’d managed before the shy, bookish Alice Portman had become Priscilla’s governess.

“Your brother is to be complimented on his friends,” Alice replied. “I liked the viscount, but he had too much dash for me. Mr. Belmont is salt of the earth in a very handsome package.”

Handsome hardly mattered compared to the knowledge in Matthew Belmont’s eyes, the quiet sense of—

Oh, dear. “Alice Portman, are you smitten?”

“Most assuredly not, but neither am I dead yet, and you would be a fool, Theresa Jennings, not to admit that man could be interested in you.”

Theresa had been the crown princess of fools until Priscilla had come along. “What if he is interested? I know what comes of gentlemen who are interested, Alice, as well as you do. A lot of clammy-handed groping, foul breath, and misery.”

From most men. Theresa had met a few of the other kind. Priscilla’s father had had more to recommend him than that. Somewhat more. He’d at least asked if she’d known how to prevent conception.

“You call your only child misery, Theresa?”

Friends were a blessing, even if they failed utterly to provide sympathy and commiseration when a woman badly needed both.

“My daughter is a bastard.” Theresa never used the word in Priscilla’s hearing, and never entirely forgot it either. “She will know a great deal of misery because I let some handsome young fellow be interested in me.” A handsome, kind-hearted, well-placed fellow, whom Theresa had carefully chosen, which only made the memory worse.

“You let the wrong fellow be interested in you. Mr. Belmont is honorable.”

“You can tell this, how?” They kept their voices down from long habit, but Theresa had nearly wailed the question. “By the elegant fit of his evening attire? By his genial repartee? By the way his sapphire cravat pin complements his marvelous blue eyes? By his appetite for chocolate cake?”

Alice peered over at Theresa, her governess-inquisition eyebrow cocked. “Did Mr. Belmont make untoward advances?”

“He did not.” Whatever Mr. Belmont had been about on that moonlit bench, it hadn’t been advances. His arm around Theresa’s shoulders had been comforting, also awkward.

She’d waited for his hands to wander, his mouth to smother hers, his conversation to turn beseeching and vulgar.

A star had fallen, the merest sigh of light against the soft, night sky. Theresa would not have seen that small miracle had Matthew Belmont not asked for a stroll in the garden. To share that fleeting wonder with him had been…

Theresa had no words for what that moment had been, no frame of reference for it at all.

Alice, however, was just full of words.

“Mr. Belmont is honorable,” Alice reiterated, nodding in agreement with herself. “He was beyond charming to Priscilla, who is not the most scintillating conversationalist for a man grown.”

“He was charming, and Priscilla would be in transports over attention from any grown man who treated her decently. That worries me.”

Theresa was relieved to have an articulable worry.

Alice closed her eyes, a woman weary of dealing with her charges. “Priscilla is a little girl. Why shouldn’t she have some attention from the man sharing an informal evening meal at her mother’s table?”