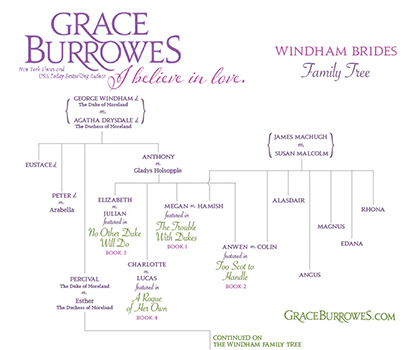

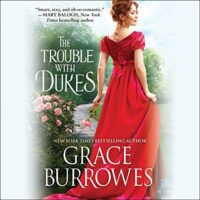

The Trouble with Dukes

Book 1 in the Windham Brides series

They call him the duke of murder…

The gossips whisper that the new Duke of Murdoch is a brute, a murderer, and even worse – a Scot. They say he should never be trusted alone with a woman. But Megan Windham sees in Hamish something different, someone different.

No one was fiercer at war than Hamish MacHugh, though now the soldier faces a whole new battlefield: a London Season. To make his sisters happy, he’ll take on any challenge – even letting their friend Miss Windham teach him to waltz. Megan isn’t the least bit intimidated by his dark reputation, but Hamish senses that she’s fighting battles of her own. For her, he’ll become the warrior once more, and for her, he might just lose his heart.

Bonus Materials →

Enjoy An Excerpt

“I don’t want any damned dukedom, Mr. Anderson,” Hamish MacHugh said softly.

Colin MacHugh took to studying the door to Neville Anderson’s office, for when Hamish spoke that quietly, his siblings knew to locate the exits.

The solicitor’s establishment boasted deep Turkey carpets, oak furniture, and red velvet curtains. The standish and ink bottles on Anderson’s desk were silver, the blotter a thick morocco leather. Portraits of well-fed, well-powdered Englishmen adorned the walls.

Hamish felt as if he’d walked into an ambush, as if these old lords and knights were smirking down at the fool who’d blundered into their midst. Beyond the office walls, harnesses jingled to the tune of London happily about its business, while Hamish’s heart beat with a silent tattoo of dread.

“I am at your grace’s service,” Anderson murmured, from his side of the massive desk, “and eager to hear any explanations your grace cares to bestow.”

The solicitor, who’d been retained by Hamish’s late grandfather decades before Hamish’s birth, was like a midge. Swat at Anderson, curse him, wave him off, threaten flame and riot, and he still hovered nearby, relentlessly annoying.

The French infantry had had the same qualities.

“I am not a bloody your grace,” Hamish said. Thanks be to the clemency of the Almighty.

“I do beg your grace’s—your pardon,” Anderson replied, soft white hands folded on his blotter. “Your great-great aunt Minerva married the third son of the fifth Duke of Murdoch and Tingley, and while the English dukedom must, regrettably fall prey to escheat, the Scottish portion of the title, due to the more, er, liberal patents common to Scottish nobility, devolves to yourself.”

Devolving was one of those English undertakings that prettied up a load of shite.

Hamish rose, and for reasons known only to the English, Anderson popped to his feet as well.

“Devolve the peregrinating title to some other poor sod,” Hamish said.

Colin’s staring match with the lintel of Anderson’s door had acquired the quality of man trying to hold in a fart—or laughter.

“I am sorry, your—sir,” Anderson said, looking about as sorry as Hamish’s sisters on the way to the milliner’s, “but titles land where they please, and there they stay. The only way out from under a title is death, and then your brother here would become duke in your place.”

Colin’s smirk winked out like a candle in a gale. “What if I die?”

“I believe there are several younger siblings,” Anderson said, “should death befall you both.”

“But this title is Hamish’s as long as he’s alive, right?” Colin was not quite as large as Hamish. What little Colin lacked in height, he made up for in brawn and speed.

“That is correct,” Anderson said, beaming like headmaster when a dull scholar had finally grasped his first Latin conjugation. “In the normal course, a celebratory tot would be in order, gentlemen. The title does bring responsibilities, but your great-great aunt and her late daughter were excellent businesswomen. I’m delighted to tell you that the Murdoch holdings prosper.”

Worse and worse. The gleeful wiggle of Anderson’s eyebrows meant prosper translated into “made a stinking lot of money, much of which would find its way into a solicitor’s greedy English paws.”

“If my damned lands prosper, my bachelorhood is doomed,” Hamish muttered. Directly behind Anderson’s desk hung a picture of some duke, and the old fellow’s sour expression spoke eloquently to the disposition a title bestowed on its victim. “I’d sooner face old Boney’s guns again than be landed, titled, wealthy, and unwed at the beginning of London season. Colin, we’re for home by week’s end.”

“Fine notion,” Colin said. “Except Edana will kill you and Rhona will bury what’s left of you. Then the title will hang about my neck, and I’ll have to dig you up and kill you all over again.”

Siblings were God’s joke on a peace-loving man. Anderson had retreated behind his desk, as if a mere half ton of oak could protect a puny English solicitor from a pair of brawling MacHughs.

Clever solicitors might be, canny they were not.

“Then we simply tell no one about this title,” Hamish said. “We tend to Eddie and Ronnie’s dress shopping, and then we’re away home, nobody the wiser.”

Dress shopping, Edana had said, as if the only place in the world to procure fashionable clothing was London. She’d cried, she’d raged, she’d threatened to run off—until Colin had saddled her horse and stuffed the saddle bags with provisions.

Then she’d threatened to become an old maid, haunting her brothers’ households in turn, and Hamish, on pain of death from his younger brothers, had ordered the traveling coach into service.

“Eddie hasn’t found a man yet, and neither has Ronnie,” Colin observed. “They’ve been here less than two weeks. We can’t go home.”

“You can’t,” Hamish countered. “I’m the duke. I must see to my properties. I’ll be halfway to Yorkshire by tomorrow. I doubt Eddie and Ronnie will content themselves with Englishmen, but they’re welcome to torment a few in my absence. A bored woman is a dangerous creature.”

“You’d leave tomorrow?” Colin slugged Hamish on the arm, hard. Anderson flinched, while Hamish picked up his walking stick and headed for the door.

“Your pugilism needs work, little brother. I’ve neglected your education.”

“You can’t leave me alone here with Eddie and Ronnie.” Colin had switched to the Gaelic, a fine language for keeping family business from nosy solicitors. “I’m only one man, and there’s two of them. They’ll be making ropes of the bedsheets, selling your good cigars to other young ladies again, and investigating the charms of the damned Englishmen mincing about in the park. Who knows what other titles their indiscriminate choice of husband might inflict on your grandchildren.”

Hamish had not objected to the cigar selling scheme. He’d objected to his sisters stealing from him rather than sharing the proceeds with their own dear brother. He also objected to the notion of grandchildren when he’d yet to take a wife.

“I’ll blame you if we end up with English brothers-in-law, wee Colin.” Hamish smiled evilly, though he counted a particular few Englishmen among his friends.

A staring match ensued, with Colin trying to look fierce—he had the family red hair and blue eyes, after all—and mostly looking worried. Colin was soft-hearted where the ladies were concerned, and that fact was all that cheered Hamish on an otherwise daunting morning.

Hope rose, like the clarion call of the pipes through the smoke and noise the battlefield: While Eddie and Ronnie inspected the English peacocks strutting about Mayfair, Hamish might find a peahen willing to take advantage of Colin’s affectionate nature.

Given Colin’s lusty inclinations, the union would be productive inside a year, and the whole sorry business of a ducal succession would be taken care of.

Hamish’s fist connected with his brother’s shoulder, sending Colin staggering back a few steps, muttering in Gaelic about goats and testicles.

“I’ll bide here in the muck pit of civilization,” Hamish said, in English, “until Eddie and Ronnie have their fripperies, but Anderson, I’m warning you. Nobody is to learn of this dukedom business. Not a soul, or I’ll know which English solicitor needs to make St. Peter’s acquaintance posthaste. Ye ken?”

Anderson nodded, his gaze fixed on Hamish’s right hand. “You will receive correspondence, sir.”

Hamish’s hand hurt and his head was starting to throb. “Try being honest, man. I was in the army. I know all about correspondence. By correspondence, you mean a bloody snowstorm of paper, official documents, and sealed instruments.”

Hamish knew about death too, and about sorrow. The part of him hoping to marry Colin off in the next month—and Eddie and Ronnie too—grappled with the vast sorrow of homesickness, and the unease of remaining for even another day among the scented dandies and false smiles of polite society.

“Very good, your grace. Of course you’re right. A snowstorm, some of which will be from the College of Arms, some from your peers, some of condolence, all of which my office would be happy—”

Hamish waved Anderson to silence, and as if Hamish were one of those Hindoo snake pipers, the solicitor’s gaze followed the motion of his hand.

“The official documents can’t be helped,” Hamish said, “but letters of condolence needn’t concern anybody. You’re not to say a word,” he reminded Anderson. “Not a peep, not a yes-your-grace, not a hint of an insinuation is to pass your lips.”

Anderson was still nodding vigorously when Hamish shoved Colin through the door.

Though, of course, the news was all over Town by morning.

![]()

“My dear, you do not appear glad to see me,” Fletcher Pilkington purred. Sir Fletcher, rather.

Megan Windham ran her finger down the page she’d been staring at, as if the maunderings of Mr. Coleridge required every iota of her attention.

Then she pushed her spectacles half-way down her nose, the better to blink stupidly at her tormentor.

“Why Sir Fletcher, I did not notice you.” Megan had smelled him, though. Attar of roses was not a subtle fragrance when applied in the quantities Sir Fletcher favored. “Good day, and how are you?”

She smiled agreeably. Better for Sir Fletcher to underestimate her, and better for her not to provoke him.

“I forget how blind you are,” he said, plucking Megan’s eyeglasses from her nose. “Perhaps if you read less, your vision would improve, hmm?”

Old fear lanced through Megan, an artifact from childhood instances of having her spectacles taken, sometimes held out of her reach, sometimes hidden. On one occasion they’d been purposely bent by a bully in the church yard.

The bully was now a prosperous vicar, while Megan’s eyesight was no better than it had been in her childhood.

“My vision is adequate, under most circumstances. Today, I’m looking for a gift.” In fact, Megan was hiding from the madhouse that home had become in anticipation of the annual Windham ball. Mama and Aunt Esther were nigh crazed with determination to make this year’s affair the talk of the Season, while all Megan wanted was peace and quiet.

“A gift for me?” Sir Fletcher mused. “Poetry isn’t to my taste, my dear, unless you’re considering translations of Sappho and Catullus.”

Naughty poems, in other words. Very naughty poems.

Megan blinked at him uncertainly, as if anything classical was beyond her comprehension. A first year Latin scholar could grasp the fundamental thrust, as it were, of Catullus’s more vulgar offerings, and Megan’s skill with Latin went well beyond the basics.

“I doubt Uncle Percy would enjoy such offerings.” Uncle Percy was a duke and he took family affairs seriously. Mentioning His Grace might remind Sir Fletcher that Megan had allies.

Though even Uncle Percy couldn’t get her out the contretemps she’d muddled into with Sir Fletcher.

“I wonder how soon Uncle Percy is prepared to welcome me into the family,” Sir Fletcher said, holding Megan’s spectacles up to the nearby window.

Don’t drop them, don’t drop them. Please, please do not drop my eyeglasses. She had an inferior pair in her reticule, but the explanations, pitying looks, and worst of all, Papa’s concerned silence, would be torture.

Sir Fletcher peered through the spectacles, which were tinted a smoky blue. “Good God, how do you see? Our children will be cross-eyed and afflicted with a permanent squint.”

Megan dreaded the prospect of bearing Sir Fletcher’s offspring. “Might I have those back, Sir Fletcher? As you’ve noted, my eyes are weak, and I do benefit from having my spectacles.”

Sir Fletcher was a beautiful man—to appearances. When he’d claimed Megan’s waltz at a regimental ball several years ago, she’d been dazzled by his flattery, bold innuendo, and bolder advances. In other words, she’d been blinded. Golden hair, blue eyes, and a gleaming smile had hidden an avaricious, unscrupulous heart.

He held her glasses a few inches higher. To a casual observer, he was examining an interesting pair of spectacles, perhaps in anticipation of considerately polishing them with his handkerchief.

“You’d benefit from having my ring on your finger,” he said, squinting through one lens. “When can I speak with your father, or should I go straight to Moreland, because he’s the head of your family?”

That Sir Fletcher would raise this topic at all was unnerving. That he’d bring it up at Hatchards, where duchesses might cross paths with milliners, was terrifying.

“You mustn’t speak with Papa yet,” Megan said. “Charlotte hasn’t received an offer and the Season is only getting started. I’ll not allow your haste to interfere with the respect I owe my sisters.” Elizabeth was on the road to spinsterhood—no help there—and Anwen, being the youngest, would normally be the last to wed.

Sir Fletcher switched lenses, peering through the other one, but shooting Megan a glance that revealed the bratty boy lurking inside the Bond Street tailoring.

“You have three unmarried sisters, the eldest of whom is an antidote and an artifact. Don’t think you’ll put me off until the last one is trotting up the aisle at St. George’s, madam. I have debts that your settlements will resolve handily.”

How Megan loathed him, and how she loathed herself for the ignorance and naivety that had put Sir Fletcher in a position to make these threats.

“My portion is intended to safeguard my future if anything should happen to my spouse,” Megan said, even as she ached to reach for her glasses. A tussle among the book shelves would draw notice from the other patrons, but Megan felt naked without her glasses, naked and desperate.

Because her vision was impaired without the spectacles, she detected only a twitch of movement, and something blue falling from Sir Fletcher’s hand. He murmured a feigned regret as Megan’s best pair of glasses plummeted toward the floor.

A large hand shot out and closed firmly around the glasses in mid-fall.

Megan had been so fixed on Sir Fletcher that she hadn’t noticed a very substantial man who’d emerged from the bookshelves to stand immediately behind and to the left of Sir Fletcher. Tall boots polished to a high shine drew the eye to exquisite tailoring over thickly muscled thighs. Next came lean flanks, a narrow waist, a blue plaid waistcoat, a silver watch chain, and a black riding jacket fitted lovingly across broad shoulders. She couldn’t discern details, which only made the whole more formidable.

Solemn eyes the azure hue of a winter sky, and dark auburn hair completed a picture both handsome and forbidding.

Megan had never seen this man before, but when he held out her glasses, she took them gratefully.

“My most sincere thanks,” she said. “Without these, I am nearly blind at most distances. Won’t you introduce yourself, sir?” She was being bold, but Sir Fletcher had gone quiet, suggesting this gentleman had impressed even Sir Fletcher.

Or better still, intimidated him.

“My dear Miss Windham,” Sir Fletcher said, “no need to ignore the dictates of decorum, for I can introduce you to a fellow officer from my Peninsular days. Miss Megan Windham, may I make known to you Colonel Hamish MacHugh, late of his majesty’s army. Colonel MacHugh, Miss Megan.”

MacHugh enveloped Megan’s hand in his own and bowed smartly. His grasp was warm and firm without being presuming, but gracious days, his hands were callused.

“Sir, a pleasure,” Megan said, aiming a smile at the colonel. She did not want this stranger to leave her alone with Sir Fletcher one instant sooner than necessary.

“The pleasure is mine, Miss Windham.”

Ah, well then. He was unequivocally Scottish. Hence the plaid waistcoat, the blue eyes. Mama always said the Scots had the loveliest eyes.

Megan’s grandpapa had been a duke, and social niceties flowed through her veins along with Windham aristocratic blood.

“Are you visiting from the north?” she asked.

“Aye. I mean, yes, with my sisters.”

Sir Fletcher watched this exchange as if he were a spectator at a tennis match and had money riding on the outcome.

“Are your sisters out yet?” Megan asked, lest the conversation lapse.

“Until all hours,” Colonel MacHugh said, his brow furrowing. “Balls, routes, musicales. Takes more stamina to endure a London season than to march across Spain.”

Megan had cousins who’d served in Spain and another cousin who’d died in Portugal. Veterans made light of the hardships they’d seen, though she wasn’t sure Colonel MacHugh had spoken in jest.

“MacHugh,” Sir Fletcher broke in, “Miss Windham is the granddaughter and niece of dukes.”

Colonel MacHugh was apparently as bewildered as Megan at this observation. He extracted Megan’s spectacles from her hand, unfolded the ear pieces, and positioned the glasses on her nose.

While she marveled at such familiarity from a stranger, Colonel MacHugh guided the frames around her ears, so her glasses were once again perched where they belonged. His touch could not have been more gentle, and he’d ensured Sir Fletcher couldn’t snatch the glasses from Megan’s grasp.

“My thanks,” Megan said.

“Tell her,” MacHugh muttered, tucking his hands behind his back. “I’ll not have it said I dissembled before a lady, Pilkington.”

The bane of Megan’s existence was Sir Fletcher, but this Scot either did not know or did not care to use proper address.

Sir Fletcher wrinkled his nose. “Miss Windham, I misspoke earlier, when I introduced this fellow as Colonel Hamish MacHugh, but you’ll forgive my mistake. The gentleman before you, if last week’s gossip is to be believed, is none other than the Duke of Murdoch.”

Colonel MacHugh—his grace—stood very tall, as if he anticipated the cut direct or perhaps a firing squad. With her glasses on, Megan could see that his blue eyes held a bleakness, and his expression was not merely formidable, but forbidding.

He’d rescued Megan’s spectacles from certain ruin beneath Sir Fletcher’s boot heel, so Megan sank into a respectful curtsey.

Because it mattered

Chapter Two

“I’ve changed my mind,” Hamish said, touching his hat brim as some duchess sashayed past him on the walkway. “We’re leaving at the first of the week.”

“You can’t change your mind,” Colin retorted, “and you just greeted one of the most highly paid ladybirds in London.”

Colin was being diplomatic, for Hamish had committed his blunder in public—where all of his best blunders invariably occurred. Three days ago, Hamish had come upon Sir Fletcher Pilkington, but at least that unwelcome moment had transpired in a bookshop.

“The lady’s clothes were expensive,” Hamish said, “and not the attire of a debutante. She smiled at me, and she had a maid trotting at her heels. How was I to know she wasn’t decent?”

“Because of how she smiled at you, as if you’re the answer to her milliner’s prayers for the next year.”

Hamish tipped his hat to another well-dressed lady who also had a maid but lacked the smile.

“The damned debutantes look at me the same way. As if I were a hanging joint of venison, and they a pack of starving hounds.”

“You aren’t supposed to greet a woman unless she acknowledges you,” Colin said as they came to a crossing.

“That last one scowled at me as if I were something rank stuck to the sole of her dainty boot. That’s the sort of acknowledgement the Duke of Murder can expect.”

A beer wagon rattled past, barrels stacked and lashed to the bed. Hamish owned two breweries, and in his present mood, he could have imbibed the inventory of both establishments and started on the distillery Colin had inherited upon coming of age.

“You need a finishing governess,” Colin said. “Or a wife.”

Oh, right. “I’m guessing among polite society, they’re much the same, which is why we’ll all be heading home by this time next week.”

Though Colin had a point. The young ladies ogling Hamish’s title all knew how to make their interest apparent without blundering. They waved their painted fans, they simpered, they smiled, but not like that. They cast lures across entire ballrooms and formal gardens, without once setting a slippered foot wrong.

The battlefield of the London Season had rules. Hamish simply hadn’t grasped those rules yet.

He’d sooner grasp a handful of blooming nettles.

“If we go home now,” Colin said, “you will never hear the end of it. Ronnie and Eddie have been invited to several balls, and depriving them of those chances to husband-hunt will earn their enmity until the day you die.”

A Scotswoman was a formidable enemy, and two Scotswomen were the match of any mere mortal man.

“When is the next damned ball?” They were all damned balls, and damned musicales, and damned Venetian breakfasts, for where Ronnie and Eddie waltzed, either Hamish or Colin must follow.

“Next week. We take the street to the left.”

Hamish did not ask how his brother knew the address of one of the most expensive modistes in a very expensive city. Colin was a good looking fellow, and he had independent means. He’d taken to the bonhomie and challenge of army life like a sheep to spring grass, and his occasional sorties to London were just so many more bivouacs to him.

“How can two otherwise intelligent women spend half the day choosing fabric?” Hamish avoided meeting the eye of an older blonde woman accompanied by a younger lady with the same color hair. “I swear Ronnie and Eddie left their brains back in Perthshire.”

“And there,” Colin murmured, “you just snubbed the Duchess of Moreland and her youngest daughter, who happens to be a marchioness.”

Hamish came to a halt. “We’re going home, ball or no ball. I’m behind enemy lines without a map, a canteen, or a sound horse, Colin. One of my blunders will soon see me married or dead in a ditch.”

Or worse, killing somebody. Hamish had been provoked to challenging one man to a duel when he’d first mustered out, but fate had interceded to prevent any serious harm to anybody. Hamish and his former dueling partner—Baron St. Clair—were even cordial now when their paths crossed.

The Baroness St. Clair was a different and less forgiving article, however.

“That’s why I’m here,” Colin said, tipping his hat to a flower girl. “To make sure you stay alive. I owe you that, and the last thing I want is a dukedom complicating my life. As long as you don’t call anybody out—anybody else out—an apology ought to cover most of your mis-steps, and you’ll soon have the lay of the land.”

Hamish resumed walking, because standing still in the middle of the walkway was enough to draw the notice of passersby.

Though perhaps, wearing his kilt hadn’t been an inspired notion. He’d hoped if any ladies were attracted by his title, they might be repelled by the sight of his bare knees. London women were apparently a stout-hearted lot, because so far, Hamish’s experiment has been a failure.

His entire visit to London had been a failure, but for that single moment when quick reflexes had spared a lady’s spectacles from harm. Hamish hoped somebody would come along to spare that same young lady from Fletcher Pilkington’s company.

That somebody wouldn’t be Hamish, more’s the pity. Miss Windham either hadn’t known or didn’t care that Hamish was the least appropriate man to hold a lofty title. Pilkington had doubtless remedied that oversight posthaste.

“Do you get the sense that Ronnie and Eddie are enjoying all this waltzing and shopping?” Hamish asked.

He and Colin had alternated coming home on winter leave, and every two years, Hamish had returned to Scotland to find taller, prettier young women wearing his sisters’ smiles. By the time he’d sold his commission after Waterloo, he’d hardly known Rhona or Edana.

They doubtless preferred not to become too well re-acquainted with their oldest brother now, though they seemed to like his new title just fine.

“The shop is down this street,” Colin said. “Tomorrow you’re due for another fitting at the tailor’s.”

“Bugger the tailor,” Hamish said. “He wants only to increase his bill. Aren’t there any Scottish tailors in this blighted city?”

“English tailors are finest anywhere,” Colin said, walking faster. “They’re the envy of every civilized man the world over. You’d bash about in your kilt and boots, swilling whisky, and embarrassing your siblings instead of taking advantage of the privileges of your station.”

Guilt assailed Hamish, the same guilt he’d felt as a captive in French hands. When he’d been led away from the scene of the ambush, bleeding in three places, his vision blurred, his head pounding and his hearing mostly gone, he’d had been in the clutches of an enemy more deadly than the French.

Shame had wrapped chains around his heart—for leading his men into an ambush, for succumbing to capture rather than dying honorably, for leaving Colin unprotected. In London, half-pay and former officers abounded, and the sooner Hamish was away from them, the better.

“My station is all the more reason for me to leave this cesspit of privilege,” Hamish said. “I do not now, nor will I ever fit in, Colin. If you didn’t want me wearing the kilt, then you might have said so before we left the house.”

Colin’s complexion was lighter than Hamish’s, and thus when Colin blushed, his mortification was apparent to all. His ears were an interesting shade of red by the time Hamish paused outside an establishment called Madame Doucette’s.

“You’re known for wearing the kilt now,” Colin said. “Once you showed up at that card party in the plaid, your fate was sealed. I’m having the full kit made up for myself.”

Colin was loyal. Hamish would not further embarrass his brother by stating his appreciation for that loyalty.

“London shops have the most ridiculous names,” Hamish said, hand on the door latch as foot traffic bustled past them. “Take this place, for instance. If I didn’t know better, I’d think from the name it was a whorehouse.”

Colin made an odd noise.

“Don’t act as if I’d just kneed you in the balls,” Hamish went on, peering through door’s glass. “Madame Doucette, my handsome kilted arse.”

Immediately behind Hamish, a throat cleared.

A battle-hardened soldier grew accustomed to the way time could expand, or the mind’s perceptions contract, so that when faced with a mortal threat, the soldier could weigh options, calculate trajectories, and assess risks in the blink of an eye.

That same sense came over Hamish in the instant necessary to perceive that the blond duchess and the little marchioness were regarding him curiously, as if not a Scotsman, but a kilted great ape had appeared on the streets of Mayfair.

“My husband has often made similar remarks about milliners’ establishments,” the duchess said. She had a smile no duchess ought to possess—wise, kind, lovely, and a hint naughty too. If Hamish lived to be a hundred, his smile would never approach this woman’s for complication, dignity, or attractiveness.

Blood would tell.

“I beg your grace’s and your ladyship’s pardon,” Hamish said. “I apologize to you both. In the military, I developed a sadly unguarded tongue.”

The young marchioness looked to be stifling a case of the giggles, while Hamish wanted to thump his head against the nearest wall.

“You might not have guarded your tongue, but you guarded your country,” her grace said, patting Hamish’s cheek as if he were a tired little fellow in want of a nap. “One has to admire your priorities, your grace, despite your colorful observations.”

The duchess swept into the shop, Colin snatching the door open at the last instant. The marchioness curtseyed prettily, winked at Hamish, and followed her mother into the modiste’s.

“I think I’m in love,” Colin muttered, when the door was once again safely closed.

“It’s nearing noon. You were overdue,” Hamish replied, charitably.

Colin smiled the slightly lost smile of a man who’d appreciated the fairer sex in six different countries, and Hamish, while not in love, certainly knew himself to be in trouble.

Deeply, deeply in trouble.

![]()

“We’re in trouble now,” Elizabeth Windham whispered, peering through the window curtains. “Aunt Esther and Cousin Evie are upon the doorstep, and we’ve yet to choose your fabric.”

Madam Doucette was still fluttering about with the pair of Scottish sisters Megan had met somewhere between the silks and the velvets. Miss Rhona and Miss Edana were both tall, merry redheads, though they lacked a fashionable sense of color.

“Not that one,” Megan said, leaving Beth’s side to take the bolt of yellow silk from Miss Edana’s grasp. “Yellow is a difficult color to wear well, though it can be a lovely accent. Say you choose this pale green, for example. A yellow lace edging to your handkerchiefs would suit, or golden-yellow bonnet ribbons and a matching parasol.”

Miss Rhona ran a hand over the yellow silk. “You even coordinate bonnet ribbons and handkerchief borders when you’re concocting an outfit?”

Didn’t everybody? “Bonnet ribbons must be some color. Why not choose a shade that suits you?”

A look passed between the sisters, as if this was a question they’d store up to fire off in some other circumstances known only to them.

Aunt Esther and Cousin Evie swept into the establishment, though mostly, Aunt Esther, who was as tall as the Scottish ladies, did the sweeping.

“My dears,” Aunt Esther said, “I considered sending out the watch in search of you. What can you be thinking, dawdling here with the ball only a week off?”

The watch was a familial euphemism for Eve’s older brothers: Lord Westhaven, Lord Valentine, and the oldest Windham cousin, Devlin St. Just, who’d soon be visiting from his earldom in the north. Megan loved her male cousins as much as she dreaded their fussing and lecturing.

The shop bell tinkled again, and all movement, all talk, ceased. Two sizable gentlemen stood immediately inside the door. They blocked enough of the light coming in the front windows to dim the sense of a happy feminine retreat.

“This green,” Miss Edana said, shoving an entire bolt of silk at Madame. “I’ve made up my mind, I’ll take the green.”

“Yes, Miss,” Madame said, scurrying to the back of the shop without even acknowledging the gentlemen.

Men came into modiste’s establishments, sometimes with a wife, a sister, or a daughter, more often with a mistress. A shrewd shop owner scheduled those visits, and used fitting salons in the back to ensure no awkwardness developed between patrons of different social strata.

These men did not belong in this shop in any capacity. The less tall fellow—he was in no wise short—was exquisitely attired in morning clothes, and bore a resemblance to the Scottish sisters.

The other fellow….

A queer feeling came over Megan, shivery and strange, but also happy, as if she’d recognized a friend from childhood whose features had altered with time, but whose countenance evoked precious memories.

In this shop of velvets, silks, and delicate lace, the larger man wore tartan wool. His kilt was a pattern of greens and blues, like lush pastures and summer sky woven about him, topped off with a dark blue velvet waistcoat, green wool jacket, and lacy white cravat.

His looks were like the textures he wore. Different, intriguing, and to Megan, attractive for their contrasts, like an arrangement of flowers in an unexpected vase.

He was not handsome, though. Too much sorrow lurked in his blue eyes, too much wariness. His features lacked refinement, but were suited to those eyes. That jaw hinted of stubbornness, and his chin reinforced an impression of implacability. Granite cliffs stood as this man did, against howling winds, crashing seas, and centuries of marching seasons.

Though at the moment, the granite-strong man was apparently felled by indecision.

“I recognize you,” Megan said, going toward him, her hand outstretched. “You rescued my spectacles yesterday in Hatchards.”

The gentleman’s expression went from wary to dismayed, as Megan took him by the arm and tugged him forward in Aunt Esther’s direction.

“You must meet my family,” Megan went on, though the gentleman was apparently not used to being led about, for he remained unyielding, despite Megan’s attempted guidance. “They will certainly want to make the acquaintance of so gallant and polite a fellow.”

![]()

Hamish knew how to survive this ambush. He must snatch Colin by the elbow, duck back out the door, and wait a safe distance down the street until Edana and Rhona were finished beggaring him.

But the bespectacled young lady with the soft voice had already taken Hamish prisoner, and to free himself, he’d have to lift her hand away from his arm. Such a maneuver required touching her, and even Hamish knew that taking liberties with a proper woman’s person was the equivalent of social suicide.

“Come along,” the lady said, patting Hamish’s hand. “Aunt is perfectly lovely, as a duchess is supposed to be.”

The perfectly lovely duchess apparently had a sense of the absurd, for she extended a gloved hand in Hamish’s direction.

“His Grace of Murdoch,” she said, “if I’m not mistaken. A pleasure, and this must be your brother, Captain Colin Murdoch.”

Colin bowed, while Hamish took the duchess’s hand and scrabbled desperately for what a man was supposed to say to a graciously smirking duchess.

“Your grace,” Hamish said, bowing. “A pleasure to meet you, and you are correct, this rascal has the honor to be my brother, Colin MacHugh.”

A flurry of curtseying and bowing and damned introducing went on for half the day. The Marchioness of Mischief was Lady Deene. The ranks of officers on the Peninsula had included a Lord Deene. The man had been a fool if he’d preferred war to remaining by his marchioness’s side.

Edana and Rhona elbowed their way into the queue, as did a pretty little thing named Miss Elizabeth Windham, another niece of the duchess.

Hamish’s sense of impatience worsened, because he had no pencil and paper with which to sketch these relationships, and he’d probably forget them before he was out the shop door. The person responsible for this trooping of the color was off in a corner polishing her glasses, half hidden by a bolt of flowery and expensive-looking fabric.

Megan Windham would be difficult to forget.

“Your grace will pardon me,” Hamish said, “but we neglect a member of your party in our exchange of pleasantries.”

Hamish had sisters, he had battlefield experience, and he had keen eyesight, even in low light. Across the shop, Miss Windham went still startled, as if she’d heard a twig snap in a forest she’d thought to enjoy in solitude.

“Megan,” her grace called in tones both pleasant and imperious. “Come make your farewell curtsey to his grace, and then we must be on our way. Madam, twenty yards of the green silk for Miss Edana, and twenty of the blue for Miss Rhona. Maroon trim for both, maroon silk shawls and slippers, maroon stockings. The young ladies will send you an additional order for petticoats and so forth at their convenience.”

Hamish was too glad for the duchess’s sense of command to quibble at the death blow she’d dealt his budget.

Miss Megan glided over to offer Colin and Hamish a curtsey. From her, the gesture wasn’t an awkward bob, but rather, an exercise in deference and grace. Everything, from the drape of Miss Megan’s skirts, to the inclination of her head, to the tempo at which she raised her hand to Hamish, was… lovely.

Colin whacked Hamish’s back.

“Madam,” Hamish said. “A pleasure.” A blessing, more like, to behold such feminine dignity, and also a sorrow. Blond, handsome Pilkington was on familiar terms with Miss Megan. For that alone, Hamish wished he’d shot the bastard when he’d had a chance.

“Your grace,” Megan said, as Hamish let her hand go. “Your sisters’ company has brightened our morning considerably, and now that we’ve been introduced, I hope they will come to call soon and often.”

“Oh, of course,” Edana said.

“We’d love to,” Rhona added.

“We’ll look forward to it,” the duchess replied, linking her arm with Miss Megan’s.

For an instant, Miss Megan appeared to resist her aunt’s gentle attempt to drag her to the door, and in that instant, Hamish locked gazes with a woman who’d provoked him to wishing.

Very bad business, when a battle-scarred soldier got to wishing for anything more ambitious than a good ale or a well-cooked joint.

“Do come by,” Megan said, her gaze unreadable behind the blue of her spectacles. “The preparations for the ball have turned our home into a mad house, and sane company will be very welcome.”

A hint of the duchess infused Megan’s parting shot. Not would you please come by, or I hope you’ll come by, but the imperative: Do come by. Hamish had given and received enough orders to know one when he heard it.

“I am sorry, Miss Megan, but my family and I are soon to depart for the north.”

If the words hurt the lady as much as they hurt Hamish, she gave no sign of it. Those spectacles were wonderful for disguising emotions. Perhaps Hamish would find a pair for himself. In Scotland, no lovely, kind, soft-spoken women peered at Hamish with honest curiosity, but nobody called him the Duke of Murder either.

“Don’t be ridiculous,” the duchess said. “You are a duke, sir, and your sisters must be presented at court if they haven’t been already. I’ll not hear of you leaving Town until that courtesy has been attended to. You will call upon us to discuss that matter, if nothing else.”

“But your grace, I have responsibilities, and we’ve tarried in London some while already,” Hamish replied, even knowing that arguing with a senior officer was folly.

“Sir, I have raised five sons,” her grace said, most pleasantly, “and I now have an equal complement of sons by marriage. Your sisters are entitled to enjoy London in every respect. You will please come to the ball on Tuesday next, and bring your siblings. Do I make myself clear? A written invitation will be in your hands by sunset.”

Rhona and Edana stood like recruits quivering to be chosen for a choice assignment, but unable to speak out of turn while they awaited their captain’s direction. In their yearning silence, Hamish saw them not as his pestering, expensive, bewildering sisters, but as two pretty young ladies who’d endured as many Scottish winters and plain wool cloaks as they could bear.

“Your invitation is most gracious,” Hamish said, suppressing the urge to salute the duchess. “We will be honored to attend, your grace.”

Honored being the prettied-up English term for doomed, of course.

![]()

Gayle Windham, Earl of Westhaven was too self-disciplined to glance at the clock more than once every five minutes, but he could see the shadow of an oak limb start its afternoon march up the wall of his study. The remains of a beef sandwich sat on a tray at his elbow, and soon his youngest child would go down for a nap.

Westhaven brought his attention back to the pleasurable business of reviewing household expenses, though Anna’s accounting was meticulous. He obliged his countess’s request to look over the books because of the small insights he gained regarding his family.

They were using fewer candles, testament to Spring’s arrival and longer hours of daylight.

The wine cellar had required some attention, another harbinger of the upcoming social season.

Anna had spent a bit much on Cousin Megan’s birthday gift, but a music box was a perfect choice for Megan.

“You haven’t moved in all the months I’ve been gone,” said a humorous baritone. “You’re like one of those statues, standing guard through the seasons, until some obliging brother comes along to demand that you join him in the park for a hack on a pretty afternoon.”

Home safe. Devlin St. Just’s dark hair was tousled, his clothes wrinkled, his boots dusty, but he was once again, home safe.

The words were an irrational product of Westhaven’s memory, for his mind produced them every time he saw his older half-brother after a prolonged absence. Westhaven crossed the study with more swiftness than dignity, hand extended toward his brother.

“Good God, you stink, St. Just, and the dust of the road will befoul my carpets wherever you pass.”

St. Just took Westhaven’s proffered hand and yanked the earl close enough for a quick, back-thumping hug.

“I stink, you scold. Give a man a brandy while he befouls your carpets, and good day to you too.”

Westhaven obliged, mostly to have something to do other than gawk at his brother. Yorkshire was too far away, the winters were too long and miserable, and St. Just visited too infrequently, but every time he did visit, he seemed…. Lighter. More settled, more at peace.

And if ever a man was happy to smell of horse, it was Devlin St. Just, Earl of Rosecroft.

“I have whisky,” Westhaven said. “I’m told the barbarians to the north favor it over brandy.”

“If you had decent whisky, I might consider it, but you’re a brandy snob, so brandy it is. How are the children?”

Thank God for the topic of children, which allowed two men who’d missed each other terribly to avoid admitting as much.

“The children are noisy, expensive, and a trial to any sentient being’s nerves. Our parents come by, dispensing a surfeit of sweets along with falsehoods regarding my own youth. Then their graces swan off, leaving my kingdom in utter disarray.”

Westhaven passed St. Just a healthy portion of spirits, though being St. Just, he waited until Westhaven was holding his own glass.

“To kingdoms in disarray,” St. Just said, touching his glass to Westhaven’s. “Try uprooting your womenfolk and dragging them hundreds of miles on the king’s highway. Your realm shrinks to the proportions of one very unforgiving saddle. Rather like being on campaign.”

St. Just could do this now—make passing, halfway humorous references to his army days. For the first two years after he’d mustered out, he’d been unable to remain sober during a thunderstorm.

“Her ladyship is well?” Westhaven asked.

“My Emmie is a saint,” St. Just countered, taking the seat behind Westhaven’s desk. “If you die, I want this chair.”

“Spare me your military humor. If I die, you and Valentine are guardians of my children.”

A dusty boot thunked onto the corner of Westhaven’s antique desk, the same corner upon which Westhaven’s own, much less dusty boots, were often propped, provided the door was closed.

“Val and I? You didn’t make Moreland their guardian?”

“His grace will intrude, meddle, advise, maneuver, interfere, and otherwise orchestrate matters as he sees fit, abetted by his lovely wife in all particulars. Putting legal authority over the children in your hands was my pathetic gesture toward thwarting the ducal schemes. You will, of course, oblige my guilt over this presumption by giving me a similar role in the lives of your children.”

St. Just closed his eyes. He was a handsome fellow, handsomer for having regained some of the muscle he’d had as a younger man.

“I can hear His Grace’s voice when you start braying about what I shall oblige and troweling on verbs in sextuplicate.”

“Is that a word?”

“Trowel, yes, a humble verb. Probably Saxon rather than Roman in origin.”

Westhaven pretended to savor his brandy, when he was in truth savoring the fact that his older brother would—in all his dirt—come to Westhaven’s establishment before calling upon the ducal household.

“Where is your countess, St. Just? She’s usually affixed to your side like a very pretty cocklebur.”

“Where’s yours?” St. Just retorted. “I dropped Emmie and the girls off at Louisa and Joseph’s, though I’m to collect them—”

The door opened, and a handsome dark-haired fellow sauntered in, Westhaven’s butler looking choleric on his heels.

“I come seeking asylum,” Lord Valentine said.

St. Just was on his feet and across the room almost before Val had finished speaking. The oldest and youngest Windham brothers bore a resemblance, both dark-haired, and both carrying with them a physical sense of passion. Valentine loved his music, St. Just his horses, and yet the brothers were alike in a way Westhaven appreciated more than he envied—mostly.

“You come seeking my good brandy,” Westhaven said, when Val had been properly embraced and thumped by St. Just. “Here.”

He passed Valentine his own portion and poured another for himself.

“We were about to toast our happy state of marital pandemonium,” St. Just said. “Or so Westhaven thinks. I’m in truth fortifying myself to storm the ducal citadel.”

Valentine took his turn in Westhaven’s chair. “I’d blow retreat if I were you.”

Westhaven took one of the chairs across from the desk. “What have their graces done now?”

Valentine preferred to prop his boots—moderately dusty—on the opposite corner from his brothers. This put the sunlight over Val’s left shoulder.

None of the brothers had any gray hairs yet, something of a competition in Westhaven’s mind, though he wasn’t sure whether first past the post would be the winner or the loser. They were only in their thirties, but they were all fathers of small children—small Windham children.

“His grace is sending Uncle Tony and Aunt Gladys on maneuvers in Wales directly after the ball,” Valentine said, “while her grace will snatch up our cousins, doubtless in anticipation of some matchmaking.”

They had four female cousins: Beth, Charlotte, Megan, and Anwen. They were lovely young women, red-haired, intelligent, and well dowered, but they were Windhams, and thus in no hurry to marry.

A situation the duchess sought to remedy.

“So that’s why Megan was particularly effusive in her suggestions that I come south,” St. Just mused, opening a japanned box on the mantel. “Emmie said something untoward was afoot.”

A piece of marzipan disappeared down St. Just’s maw.

“Goes well with brandy,” he said, offering the box to Val, who took two. “Westhaven?”

“How generous of you, St. Just.” He took three, though the desk held another box, which his brothers might not find. His children hadn’t.

Yet.

“Beth and Megan have both been through enough seasons to know how to avoid parson’s mousetrap,” Westhaven said.

“I wondered what their graces would do when they got us all married off,” Valentine mused, brandy glass held just so before his elegant mouth. “I thought they’d turn to charitable works, a rest between rounds until the grandchildren grew older.”

He tossed a bit of marizipan in the air and caught it in his mouth, just he would have twenty years earlier, and the sight pleased Westhaven in a way that he might admit when all of his hair was gray.

“Beth is weakening,” Westhaven said. “She’s become prone to megrims, sore knees, a touch of a sniffle. Anna and I do what we can, but the children keep us busy, as does the business of the dukedom.”

“And we all thank God you’ve taken that mare’s nest in hand,” St. Just said, lifting his glass. “How do matters stand, if you don’t mind a soldier’s blunt speech?”

“We’re firmly on our financial feet,” Westhaven said. “Oddly enough, Moreland is in part responsible. Because he didn’t bother with wartime speculation, when the Corsican was finally buttoned up, once for all, our finances went through none of the difficult adjustments many others are still reeling from.”

“If you ever do reel,” Valentine said, “you will apply to me for assistance, or I’ll thrash you silly, Westhaven.”

“And to me,” St. Just said. “Or I’ll finish the job Valentine starts.”

“My thanks for your violent threats,” Westhaven said, hiding a smile behind his brandy glass. “Do I take it you fellows would rather establish yourselves under my roof than at the ducal mansion?”

Valentine and St. Just exchanged a look that put Westhaven in mind of their parents.

“If we’re to coordinate the defense of our unmarried lady cousins,” St. Just said, “then it makes sense we’d impose on your hospitality, Westhaven.”

“We’re agreed then,” Valentine said, raiding the tin once more. “Ellen will be relieved. Noise and excitement aren’t good for a woman in her condition, and this place will be only half as uproarious as Moreland House.”

“We must think of our cousins,” St. Just replied. “The combined might of the duke and duchess of Moreland are arrayed against the freedom of four dear and determined young ladies who will not surrender their spinsterhood lightly.”

“Nor should they,” Westhaven murmured, replacing the lid on the tin, only for St. Just to pry it off. “We had the right to choose as we saw fit, as did our sisters. You’d think their graces would have learned their lessons by now.”

A knock sounded on the door. Valentine sat up straight, St. Just hopped to his feet to replace the tin on the mantel, and was standing, hands behind his back, when Westhaven bid the next caller to enter.

“His Grace, the Duke of Moreland, my lords,” the butler announced.

In the next instant, Percival Windham stepped nimbly around the butler and marched into the study.

“Well done, well done. My boys have called a meeting of the Windham subcommittee on the disgraceful surplus of spinsters soon to be gathered into her grace’s care. St. Just, you’re looking well. Valentine, when did you take to wearing jam on your linen?”

Moreland swiped the tin off the mantel, opened it, took the chair next to Westhaven and set the box in the middle of the desk.

“I’m listening, gentlemen,” the duke said, popping a sweet into his mouth. “Unless you want to see your old papa lose what few wits he has remaining after raising you lot, you will please tell me how to get your cousins married off post haste. The duchess has spoken, and we are her slaves in all things, are we not?”

Westhaven reached for a piece of marzipan, St. Just fetched the brandy decanter, and Valentine sent the butler for sandwiches, because what on earth could any of them say to a ducal proclamation such as that?

![]()

The Duke of Wellington had expected all of his direct military reports to know how to waltz, and thus Hamish had made it a point never to learn. His grace had also preferred officers with titles and aristocratic lineages. When conversation in the officers’ mess had turned to women, war, and wagering, Hamish had brought up breweries, distilleries, and commerce.

Trade in all its plebian glory.

As a result, Hamish had no idea what sort of small talk was expected when calling on a duchess.

“Colin, you’ll accompany our sisters inside,” Hamish said, while Rhona and Edana perched on the very edge of the coach’s forward facing seat. The vehicle was more properly a traveling coach than a town coach, because four MacHughs did not fit comfortably in the toy carriages favored by polite society.

“Hamish, Miss Megan invited you,” Rhona said.

“And the duchess ordered you to come along with us,” Edana added. “The Duchess of Moreland, who can ruin somebody with the lift of her eyebrow.”

Hamish knew exactly which duchess, though the woman would probably be bored merely ruining somebody. If she took a man into dislike, there’d be nothing left of him to be ruined. She was the worst variety of foe—the worthy sort in full command of her foot, horse, and cannon.

Colin opened the carriage door and sat back. On the cobbles, Old Jock stood by, chest puffed out, doing his best to uphold the dignity of the house of MacHugh.

Shamed by an arthritic coachman.

Hamish climbed out of the carriage, which undertaking rocked its inhabitants. Edana followed, but remained half in, half out, her gloved hand extended.

“Eddie, for God’s sake,” Hamish said, hauling her the rest of the way out. “You’ve been getting in and out of coaches since you were a wee pest. You could drive this coach better than Old Jock,”—an indignant breath sounded at Hamish’s elbow—“when he’s been swimming in the whisky barrel. Stop hanging on me.”

Her eyes narrowed in a fashion that would have sent the last wolf in Scotland fleeing into the sea.

Colin emerged from the coach and turned to assist Rhona. “Let’s bicker away the morning on the duchess’s very doorstep,” he suggested, “knocking on her door being tediously predictable.”

“You were supposed to send a footman in with your card,” Rhona said, smoothing her hand over skirts that had probably cost more than the coach.

Now she bothered to inform her own brother of the niceties? “Why get trussed up in my finest, put up with you lot, trouble the horses—and our Jock—just to send around a stupid card for which the bloody printer seeks to charge daylight robbery rates, which I am not about to pay?”

Edana’s grip on Hamish’s arm dug into the tender spot in the crook of his elbow. Knew all a man’s vulnerable points, did Edana, because Hamish had taught them to her.

“You left the house without your calling cards? Hamish, how could you?”

He thrashed free of her grip. “It’s like this, Eddie. If you let the trades know they can steal from you, they steal from you. Rules of battle, plain and simple. If the enemy retreats, you rout him. If the enemy stands his ground, you engage him. You do not hand over your hard-earned coin with a superior smile like some infernal, mincing duke who hasn’t got a brain in his idiot English head.”

Somebody shut the coach door with a bang. “I make it a point never to mince, not even when private with my duchess.”

Colin’s features went blank, Rhona studied her slippers—pink of all the useless colors—and Edana for once had nothing to say.

A tall, lean, older gentleman in riding attire stood beside Hamish’s coach—blocking any retreat back into the coach, in fact. The fellow had shrewd blue eyes, and his hair was the pale gold of an aging Saxon warrior.

Hamish had likely insulted the man on his own doorstep. “My apologies for bickering with my siblings on the very street.” He ought probably to have bowed, for this fellow was doubtless a damned duke, but taking his eyes off the gentleman seemed ill-advised.

“Percival, Duke of Moreland, at your service. I have a small but precious cohort of grandchildren, and eight grown children, sir, all of them wed. Bickering is the music of a family with nothing serious to fight about.”

Also the music of a family that hadn’t progressed to the breaking-furniture-and-hurling-oaths stage of a difference of opinion.

Colin’s elbow jabbed at Hamish’s ribs.

“Hamish, Duke of Murdoch, your grace.”

Edana’s elbow hammered him from the other side, which made no sense. A duke was a “your grace,” of that, Hamish was certain.

“You’re paying a call on my duchess,” Moreland said, striding up the walk. “We can continue the introductions inside and prevail upon her grace for some sustenance. The social season can be exhausting, but I assume you’ve already found that out.”

Introductions.

Well, of course. Polite society apparently had nothing better to do than exchange an endless lot of tedious introductions. Even in the military, which had been polluted with titled lords and aristocratic younger sons, protocol had wasted as much time as polishing weaponry.

Edana took Hamish by one elbow, Rhona got him by the other, and thus he was press-ganged into the ducal mansion, Colin trailing behind.

“Alert the ladies,” the duke said to the footman who opened the door. “I found a stray duke wandering about on the walkway, with his two lovely sisters and a handsome brother, no less.”

“Of course, your grace. The ladies are in the green parlor, and I’ll let the kitchen know more guests have arrived.”

“Come along,” Moreland said, setting off at a brisk pace. “Her grace is doubtless expecting you, though I warn you: She’s in the throes of planning a ball for our nieces. I tread very lightly at such times, and I’m a veteran of His Majesty’s Canadian campaigns.”

That a military veteran and a duke, no less, was daunted by an upcoming ball comforted Hamish not one bit.

Neither did the Moreland dwelling. The ducal mansion was a monument to fanciful plaster work, with porcelain vases tucked into alcoves, hot house flowers arranged with artless grace, and light glinting off gilt pier-glasses. The carpets were thick enough to muffle the duke’s boot steps. Hamish was reduced to silently towing his sisters forward, lest they become transfixed by the sheer wealth on display.

Wealth and good taste. Hamish recognized good taste mostly because he hadn’t any himself. He had breweries and battle scars, and now several awestruck siblings.

The Moreland mansion was hell with an English accent, at least for Hamish.

“Murdoch, perhaps you’d best introduce your family to me before we brave the gauntlet within,” the duke said. “Her grace will have all in hand, but a fellow likes to impress his duchess whenever possible.”

Moreland’s tone was genial, and the smile he turned on Edana and Rhona hinted at the handsome young officer who’d strutted around Canada decades before. And yet, Hamish would comply with his grace’s request, and not because manners required him to.

He’d oblige Moreland with a rehearsal of the introductions because Moreland had campaigned in Canada years ago—a place as beautiful as it was dangerous—and because the officer in Hamish respected competent command when he saw it.

He’d seen plenty of the other kind, and been guilty of it too.

Two minutes later, the duke flourished the parlor doors open and led his guests into another room full of light, lovely, priceless appointments. The golden-haired duchess perched among four red-haired young women, two of whom Hamish didn’t recognize.

Miss Beth Windham sat to the right of the duchess, who brightened visibly at the sight of the duke, as if a rider bearing dispatches had come safely through the lines.

Opposite them was Miss Megan, and right beside her sat Sir Fletcher Pilkington, like a spider idling about in the middle of a gossamer web.

![]()

Aunt Esther had explained to Megan long ago that introductions followed a set pattern so a woman had time to memorize names and titles. When Megan had met Sir Fletcher for the first time, she had silently repeated a silly rubric: His name is Sir Fletcher, he could never be a lecher.

A man so goldenly gorgeous, graceful, and charming would not have to press his attentions on a woman. She’d hand over her entire evening to him, and half of her dignity, without being asked.

Alas, Megan had handed over even more than that.

“Ah, Moreland!” Aunt Esther said, beaming at her duke. “You have brought friends to enliven our day.”

Uncle Percy assisted his duchess to her feet, beaming right back at her.

Some of their graces’ effusive mutual regard was for public consumption—Uncle Percy did love to make an entrance—but much of it was genuine.

“My dear,” Uncle Percy said, bowing over Aunt Esther’s hand, “the Duke of Murdoch has come to call and brings his siblings. We will need a larger parlor at the rate you’re collecting gallants this season.”

Sir Fletcher was on his feet, muttering polite greetings over the hands of the MacHugh sisters, while their oldest brother hung back, his blue-eyed gaze watchful.

“Anwen,” Aunt Ester said, “might you have the kitchen send us a fresh pot and some sandwiches to the terrace? The morning is lovely, and the gardens are coming along nicely.”

Anwen shot Megan the barest glance of sympathy and scampered off, likely not to be seen for hours.

“Good morning, your grace,” Megan said, taking the Duke of Murdoch by the arm before Sir Fletcher could attach himself to her side. “Shall we repair to the garden?”

His expression could have frozen the Thames in July. “Aye.”

Sir Fletcher offered an arm to Lady Edana, Uncle Percy escorted Lady Rhona, and Colin MacHugh was left to accompany her grace. All very friendly and informal, and so tediously gracious Megan wanted to shriek.

“Uncle Percy is proud of his roses,” she said, leaning closer to the Scottish duke. “It’s too early for them, but if you compliment the gardens generally, he’ll be pleased.”

Murdoch glowered at her. “Your uncle hasn’t held a pair of pruning shears since Zaccheus climbed down from the sycamore tree. Why would I compliment Moreland on gardens he never tends himself?”

The question was appallingly genuine, maybe even a touch bewildered.

“You are brand new duke, he’s a duke of great consequence. His favor could benefit you,” Megan said, starting from simple premises. “Uncle is responsible for these gardens, for hiring the gardeners and supervising their progress. If the gardens prosper, Uncle Percy has managed them and those who tend them well.”

“Meaning no disrespect, miss, but that’s not the way of it.”

Sir Fletcher laughed at something Lady Edana said. He probably practiced laughing before his shaving mirror, he looked so charming and elegant when overcome with mirth. He tossed back his head, injected just the right quantity of merriment into his laughter, angled his smile with a calculated degree of warmth—

“I beg your pardon,” Megan said, hauling her attention back to her escort. Murdoch looked like the word laughter had yet to find its way to his vocabulary. “I believe I grasp how Uncle Percy’s household works quite well, your grace. Shall we find a seat?”

A bench, so Megan could sit on one end, and put the duke on her only available side.

“Firstly,” the duke said, keeping his voice down, “your uncle loves the gardens because they make his duchess happy. I suspect these gardens hold memories too, mostly the cheerful sort. The gardener is likely some old fellow who’s been on the job since his grace was in leading strings, and the duke has little to say about any of it. Couldn’t turn the old blighter off if he killed every posy on the premises. Wealth only looks like it gives a man power. In truth it makes him less free.”

The gardener was a fixture by the name of Murray. Megan had no idea whether that was a first name, a last name, or a nickname. He was simply Murray, and regarding the garden, he was an absolute, if kindly, dictator.

“What’s secondly?” Megan asked, as the duke lead her across the terrace and down the steps into the garden proper.

“Secondly, Miss Meggie, if you hate a man, you mustn’t do it so others take notice.”

Miss Meggie. Oh, how the duke transgressed the bounds of decorum, and how she liked his familiarity.

“I don’t hate you. I barely know you.”

“I refer to Sir Fletcher. Maybe you’re jealous of the attention he shows my sister, but you needn’t be. I will gut the varlet where he stands if he thinks to take anything approaching a liberty with my Eddie.”

Megan wished Sir Fletcher would take liberties with Lady Edana, with any young woman in a position to hold him accountable for his scoundrel ways. She wished all men were as given to honest speech as Murdoch, and she wished she’d met this gruff Scotsman much sooner.

“You’re notions of family loyalty are quite violent,” Megan said. “Is that why you’ve been dubbed the Duke of Murder?”

Chapter Three

The Duke of Murder?

Miss Megan’s gaze was merely curious. She couldn’t know how that sobriquet twisted in Hamish’s gut like a rusty bayonet in enemy hands.

“That’s what they’re calling me, aren’t they? I suppose it fits.”

She patted his arm. “You were a soldier. My cousins Devlin and Bart were soldiers. Devlin came home the worse for his experiences, Bart lost his life in Portugal. War results in a lot of ugly death. Even ladies grasp that unfortunate reality.”

Ladies—a few ladies—might grasp the generalities, but no lady should have to hear the details as Hamish had lived them.

“Tell me about this ball, madam. I’ve been to a few of the regimental variety, but they’re mostly about staying sober until the womenfolk go home, and cutting a dash in dress uniform.”

Her gaze went to Sir Fletcher, who was courting death by standing too close to Edana. Colin was monitoring the situation from the duchess’s side, and Rhona stood nearby with Moreland. Sir Fletcher was surrounded, did he but know it.

If he thought to offer for Edana, he was a worse fool than Hamish knew him to be.

Miss Megan was a calm sort of lady, or maybe those blue-tinted spectacles gave her a calm air. She trundled along beside Hamish, preserving him from all the small talk and silliness transpiring on the terrace.

“A ball is a test of endurance,” Miss Megan said. “Think of it as a forced march. You provision as best you can, but traveling lightly is also important. Dress for comfort, not only to impress. Eat little beforehand, for there will be abundant food and drink, and study the morning’s newspaper so you’ll have some conversation to offer your dinner partner.”

Hamish had carried men on his back through the snow on the retreat to Corunna. Not merely a forced march, but a complete rout, the pursuing French promising death for any who faltered. He’d sooner endure another such march than the London Season.

“It’s that sort of ball, with dinner partners?”

“One dinner partner, usually, though people congregate in groups too. Your partner for the supper waltz is generally your dinner companion, and the supper waltz tends to happen around midnight.”

She peered at him, a man facing doom. “Shall I save my supper waltz for you?”

Sir Fletcher would hate that. Hamish had studied the assembled company as the introductions had plodded on, and Major Sir Fletcher Pilkington was an accepted friend of the Moreland household. He’d been sitting practically in Miss Megan’s lap, and she’d tolerated that presumption.

And yet, in the bookshop, Sir Fletcher had been bullying the lady.

“Sir Fletcher hasn’t spoken for your waltz?” Hamish asked.

Miss Megan had led them to a fountain that featured a chubby Cupid with an urn on one shoulder and a slightly chipped right wing. She took a seat on a bench flanking the fountain, which meant Hamish could sit as well—as best he could recall.

“Sir Fletcher is much in demand as a dancing partner,” Miss Megan said.

He’d been a slobbering hound where the camp followers were concerned, until they became acquainted with his temper. That, of course, had been several years ago, and Hamish hoped not to be judged exclusively by his conduct in the military.

A vain hope, apparently.

“Sir Fletcher is a jackass,” Hamish said, perching on the edge of the fountain. “If that insults your intended, I do apologize, but you deserve better.” Any woman deserved better than Sir Fletcher Pilkington.

“He is the son of a viscount, a decorated war hero, and considered handsome,” Miss Megan said. “Uncle Percy has assured me Sir Fletcher’s prospects are sound enough.”

Then Uncle Percy hadn’t bothered to ask the moneylenders who watched the comings and goings at the Horse Guards. Too busy flirting with his duchess, perhaps. He’d be better off protecting his niece’s flank, as it were.

“So you’ll waltz with your Knight of the Sound Prospects,” Hamish said, not liking the idea at all. “You’ll make a fetching couple. That matters to some.” Though Miss Meggie didn’t strike him as a lady to be taken in by a handsome face or a lot of flirtatious blather—and those were Sir Fletcher’s best qualities.

“Please sit beside me,” Miss Megan muttered.

“I beg your—?”

She got a grip on Hamish’s sleeve and hauled stoutly. He took the place to her right.

“You’re the determined sort,” he said. “Edana and Rhona are too, but they’ve had to be.”

“They are Lady Edana and Lady Rhona now,” Miss Megan said. “You have become a duke, so your siblings’ status has changed as well.”

Hamish’s bank balance had certainly changed. “My pismire of a solicitor said something about this, though he said it would cost considerably and take some time. I haven’t mentioned anything to my sisters about acquiring the title lady.”

Miss Megan slipped her glasses down her nose to peer at Hamish. “You brother also becomes a courtesy lord. All it takes is a Warrant of Precedence signed by King George. I think you must ask for my supper waltz, your grace.”

As if the king was about to extend favors to the Duke of Murder? “Madam, there’s no point to my asking for your supper waltz.”

If Hamish were to waltz with any woman, though, it would be Megan Windham. She didn’t put on airs, she was quiet, and in an understated, easily overlooked way, she was lovely.

“Ask me anyway.” She sounded much like her auntie, the Duchess of Doom.

“Miss Meggie, though it pains me to admit it, I’m nearly famous for not knowing how to waltz. I’d embarrass us both and likely end up on my kilted arse before all of polite society.”

This time, she patted his hand. “Nonsense. If I can learn to waltz, so can you. Tomorrow afternoon should suffice. Bring your sisters, I’ll round up a few of my cousins, and we’ll have an impromptu tea dance at my cousin Westhaven’s townhouse.”

Moreland was teasing Rhona, who was a shy soul when she wasn’t threatening mayhem for want a few dresses. Lady Rhona, according to Megan Windham. Hamish needed to know more about that Warrant of Whatever, and for his sisters’ sakes, he needed to learn to waltz.

“Name a time, and promise me this gathering will be private,” he said. “I’ll not be falling on my backside for the entertainment of half of Mayfair.”

Sir Fletcher was sauntering up the path, Edana beside him. Damned if she didn’t look half-smitten, more’s the pity.

“You’ll not be falling on your backside at all,” Miss Megan said, “but you are not to leave my side so long as Sir Fletcher is about, do you understand, your grace?”

Hamish did not in the least understand, though he hoped Miss Megan’s order—for it was an order—meant she had a few reservations where Sir Fletcher was concerned. What Hamish knew for certain was that he had somehow been talked into letting this little, bespectacled blue-blood teach him to waltz, and worse, he was looking forward to that ordeal.

![]()

“A word with you, your grace.”

Hamish looked about, wondering when somebody had let a bloody damned duke into the conversation. Across the music room, Megan Windham was sorting through music at the piano, Edana and Rhona by her side.

The three fellows surrounding Hamish were Miss Megan’s cousins, and by some sleight of hand known only to English dukes, all three cousins were titled.

“Beg pardon,” Hamish said. “The ‘your grace’ bit will take some getting used to. You might as well know I can’t waltz for shite.”

“Language, Murdoch,” the biggest of the three muttered. The one with all the lace at his throat and wrists took to studying the parquet floor in the manner of a gunnery sergeant trying not to murder his own recruits on the first day of target practice.

“I honestly cannot waltz,” Hamish said, hoping Miss Meggie could at least play the piano. Rhona and Edana had a few passable tunes memorized, but they were no substitute for an orchestra.

“If Megan has decreed that you’re to learn to waltz,” the auburn-haired fellow said, “then you shall learn to waltz. She is soft-hearted, and we will not allow you to disappoint her.”

Lord Shall and Allow must be the ducal heir.

“That’s good,” Hamish replied, making sure his sporran hung front and center. “You ought to be protective of her, because she’ll have no toes left if she dances with me.” Very pretty toes they likely were too.

“She will have all of her toes,” the nancy brother said. “Can your sisters waltz?”

“I expect so. They’ve had a dancing master coming around for the past three years. Expensive little shi— blighter, too.”

“Then let’s be about it,” Lord Nancy Pants said. He wore as much lace as a French colonel intent on impressing the ladies, but had a good set of shoulders too. “Ladies, if you’d choose your partners, the entertainment portion of the afternoon is about to begin.”

Edana took the heir, Rhona made her curtsey to big fellow cousin, and Hamish was left…

“You’re not wearing your specs,” he said, as Miss Megan rose from a graceful curtsey.

“The year I made my come out, they went sailing off my nose in an energetic turn, and landed in the men’s punch bowl. I haven’t worn them on the dance floor since. Shouldn’t you bow, your grace?”

She offered her bare hand—this was a practice dance, after all—and Hamish executed the requisite gentlemanly maneuver.

“Now what?”

“Now Lord Valentine will play the introduction….”

God above, the nancy bastard knew his way around a keyboard. This was not the tortured thumping Hamish associated with country dances and overheated ballrooms, this was music.

“Slower!” Miss Megan called, and the speed of the music calmed, though the melody acquired more twiddles and faradiddles along the way. “We’ll need a lengthy introduction as well.”

“More introductions?” Hamish muttered.

Her eyes were truly lovely without the spectacles, large, guileless, the blue of the Scottish sky over high pastures in spring.

“The waltz is in triple meter, like the minuet,” Miss Megan said. “One-two-three, one-two-three, but all you need to do is feel the downbeat.”

Scotsmen were born to dance. They had no particular defenses against being handled by determined women, though. Miss Megan put one hand on Hamish’s shoulder and grasped his hand with the other.

“Your free hand goes above my waist, toward the middle of my back, but not quite. You want it where you can guide me. Your grace, it’s customary to assume waltz position when contemplating the waltz.”

Hamish longed to touch her—to assume this genteel, slightly risqué, elegant dance pose with her—and he didn’t dare.

“I might knock ye over,” he said, hoping the twiddles and faradiddles kept his words from her cousins’ notice.

“You cannot possibly. I’ll simply turn loose of you and step back should your balance become questionable. The simplest way to learn the waltz is to pattern your steps like a square…”

Hamish’s balance had become questionable back in Hatchards bookshop, when he’d heard Pilkington sneering and strutting through a conversation with a lady. He’d lost his balance all over again at the dress shop, and pitched it into Moreland’s prize roses in the ducal garden too.

Miss Megan nattered on, all the while the other couples twirled and smiled around them, the music lifted and lilted, and Hamish wanted to kill Sir Fletcher Pilkington. The ability to flirt in triple meter had seen the younger son of an English lord elevated to the point where he got good men killed, and men only half-bad flogged nearly to death.

“You look so fierce,” Miss Megan said, when they were on their second lurch about the room. The lady, fortunately, was more substantial than she looked, and determined on Hamish’s education.

“I’m concentrating. Anything more complicated than a march and a fellow gets confused.” Her perfume was partly responsible, half spice, half flowers. Not roses, but fresh meadows, scythed grass, lavender and…

He brought the lady a trifle closer on a turn, the better to investigate her perfume, and between one twirl and the next, his instructress became Hamish’s every unfulfilled dream on a dance floor. She had the knack of going where a fellow suggested, as if she read a man’s intentions by the way he held her.

Miss Megan made Hamish feel as if spinning about in his arms sat at the apex of her list of joys, the memory she’d recount in old age to dazzle her great-nieces and grand-daughters. She danced with the incandescent joy of the northern lights, and all the feminine warmth of summer sun on a Scottish shore.

To her, he was apparently not the Duke of Murder or the Berkserker of Badajoz. He was simply a lucky fellow who needed assistance learning to dance. The relief of that, the pleasure of shedding an entire war’s worth of violence, was exquisite.

For another turn down the room, Hamish wallowed in a fine, miserable case of heartache, for this pleasure was illusory—he had killed often and well—and the lady could never be his. Worse yet, she apparently belonged to that walking hog wallow of dishonor and guile, Sir Fletching Pukington.

The sooner Hamish waltzed his own titled, homesick arse back to Scotland, the better for all.

![]()

The Duke of Murdoch was all grace and power, and his protestations about not knowing how to waltz must have been for his sisters’ sakes. Soldiers could be shrewd like that. St. Just, Westhaven, and Valentine would surely beg a set from the ladies as a result of this informal rehearsal, and Murdoch had probably known as much.

“A couple usually converses during a waltz,” Megan said, as they started on another circle of the music parlor. “How do you find London, that sort of thing?”

Murdoch’s sense of rhythm was faultless, but he’d apparently misplaced the ability to smile—at all.

“Find London? You go down the Great North Road until you can’t go any farther, then you follow the noise and stink. Can’t miss it. I prefer the drover’s routes myself. The inns are humble, but honest.”

Megan’s mother was Welsh, so a thick leavening of Celtic intonation was easily decipherable to her. She switched to Gaelic, as she occasionally did with family.

“I meant, does London appeal to you?”

Nothing had broken his grace’s concentration thus far. For dozens of turns about the room, despite Westhaven and St. Just’s adventuresome maneuvers with Murdoch’s sisters, and Valentine’s increasingly daring tempo, the duke had become only more confident of his waltzing.

One simple question had him stumbling.