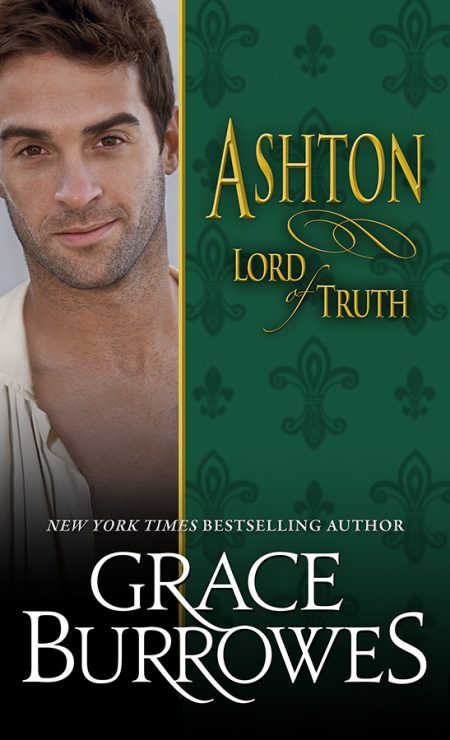

Ashton

Lord of Truth

Book 13 in the Lonely Lords series

Ashton Fenwick was raised to be the bastard older brother—the charming, happy bastard older brother—but now an earldom has been foisted upon him. His family urgently needs him to find the right countess, and the best place to look for prospective countesses is London during the social Season. With charm at the ready, Ashton is prepared to go wife-hunting, though it’s the landlady at his lodging house who catches his eye—and his heart.

Matilda Bryce bakes a delicious apple tart and does not suffer fools. Ashton falls hard for a woman who doesn’t put on airs, even as she looks after street urchins and does what she can to acquaint him with the challenge before him. As Ashton gets to know Matilda better, he realizes somebody is out to destroy her happiness. He’s found the lady for him, but before he can make an honest countess of her, he must risk all to free Matilda from her past.

Enjoy An Excerpt

Chapter One

“I am the bastard,” Ashton Fenwick said. “I am the charming, firstborn bastard, and I’m good at it. Now you want to wreck everything. Is this your idea of fraternal loyalty?”

Ewan had the grace to look abashed. “As a matter of fact, it is. You will make a fine earl.”

His rejoinder came in accents that were nearly Etonian—baby brother had attended Harrow—while the dialect of the Borders lurked beneath Ashton’s every syllable.

Alyssa remained silent on the red velvet sofa, wearing her don’t make me cry expression. The absolute unfair hell of it was, when Ashton’s sister-in-law looked as she did now—eyes glistening, gaze resolute—he was nearly moved to tears himself.

“I will make no sort of earl at all,” he said, pacing the length of the estate office. Because the estate belonged to the earl—not to Ashton—the chamber was spacious and the carpets thick enough to muffle his boot steps. “I stink of horses more often than not. I swear in at least four languages, I am ever so fond of a wee dram, and I am not the perishing, sodding, bedamned earl.”

Ashton had raised his voice, a Scotsman’s prerogative when making a point to another hardheaded Scotsman.

“You have enumerated at least three characteristics of the typical lordling,” Ewan said. “A titled man also, however, sires progeny on command, and that I have failed to do.”

Ashton sent Alyssa an accusing glower. “I heard a sniffle. We’ll hae none o’ that snifflin’ in this discussion. A countess doesna sniffle.”

“I don’t care if you’re the bloody Duke of Argyll,” Ewan retorted, marching up to Ashton. “You do not address my wife in such a fashion.”

Ewan was an inch shorter than Ashton, probably the besetting disappointment of his lordship’s handsome life. Though Ewan was the younger brother, he’d been the earl since the age of twenty-two, and his skill with a verbal command was impressive.

“You even sound like an earl,” Ashton said, patting his brother’s lacy cravat. “You have earl hair, while I resemble a two-legged black bear.”

One blond eyebrow lofted to an angle only a titled fellow could achieve. “Have you been drinking, Ash?”

“Of course, I’ve been drinking. A wee dram makes life rosier, so I’ll just be helping myself to one now.” Ewan hadn’t offered him libation, because Ashton wasn’t quite a guest at the family seat, and yet, he wasn’t entirely family, despite being Ewan’s full brother.

Alyssa exchanged a look with her husband that conveyed love, pleading, and more than a little pain. Ashton ignored that glance, filled two glasses with the best whisky the estate had to offer, downed both, then refilled them.

“To the earl,” Ashton said, the toast he and his brother had been making for years.

“To the earl,” Ewan echoed, his weary tone plucking at Ashton’s last nerve.

“Why bring this up now?” Ashton asked. “You’ve sat on this information for months. Why do you choose now to ruin my future?”

“You call immense wealth, prestige, influence, a life of security and ease ruin?” Ewan asked.

The question was genuine, which made it that much more heartbreaking.

“Ewan, you were raised to value all of this,” Ashton said, sweeping a hand in the direction of ornate pier glasses, intricate plasterwork, exquisite landscapes, and delicate gilt chairs each of which was worth more than Ashton’s best horse.

“You were raised to value it as well,” Ewan retorted, setting his barely touched drink on the sideboard. “Most people would have the sense to value beauty, comfort, and security.”

“Why value what you know you can never have?” Ashton asked. “I was warned over and over by every tutor and headmaster that I had to make something of myself, that nothing would be handed to me.”

“And yet, you were given an education, a roof over your head, love, a place to call home, skills, and above all, freedom to follow your own direction. As the only legitimate heir, I was wrapped in cotton wool, chaperoned, and lectured until I was nearly mad with it.”

Ewan strolled to the window—no pacing about for him—as if mesmerized by a view of southern Scotland he’d had nearly thirty years to study. Thanks to a river that changed course every hundred years or so, a portion of the estate touched into England. The previous earl had considered diverting the river to rectify that disgrace.

“Tell him, Ewan.” Alyssa’s voice was husky, as if she’d already endured a bout of tears. “If you don’t, I will.”

The whisky curdled in Ashton’s gut. “Is somebody ill?”

He loved these people as only a lonely Scotsman could love his two extant immediate family members. In the past five years, Ashton and Ewan had lost one sister to influenza, and another to a lung fever. If Ewan or Alyssa were unwell—

“Not ill,” Ewan said. “But in a delicate condition, nonetheless.”

Ashton dropped onto the sofa beside Alyssa. “Now that’s a fine thing. You had me worried when I should be rejoicing. I’ve never been an uncle before, but I’m sure I’ll get the knack of it. Spoiling a wee niece or nephew is what uncles do best, and now that you’ve given me some warning—”

Alyssa put her head in her hands. “Ewan, make him understand.”

Ashton shut his mouth, because when Alyssa Jean MacDermott Fenwick took to pleading, the end times were surely nigh.

“Alyssa has conceived before,” Ewan said, back to the room. “We’ve lost the child in the early days all three times. This time seems to be going better.”

Currents swirled about the elegant room, entirely human currents of anxiety, hope, and heartbreak. Some forms of wealth, not even a title could buy.

“Tell him the rest of it,” Alyssa said.

“There has been talk,” Ewan went on, fiddling with the red velvet tie holding the curtains in their precise, elegant folds. “Mama’s old nurse has grown doughty, and she wanders. Gunna found her way to the pub last summer and began reminiscing. Her sister, who is still quite sharp, didn’t contradict her, and the talk hasn’t gone away.”

“We’re in Scotland,” Ashton said, patting Alyssa’s hand. Her fingers were cool, and now that he was next her, she struck him as pale. “People will talk when they’re not vying for a spot on the sinner’s stool.”

Alyssa winced at his reference to fornication, but without that particular vice, the stool at the front of the kirk would get a good deal less polishing by penitential backsides.

“The problem, brother, is that the talk is true. Alyssa was in the attics rummaging among the nursery trunks, and she found Mama’s diary, from when Mama and Papa eloped.”

“Diaries can be falsified.”

Even as he spoke, Ashton felt the weight of doom closing in on him. A small Scots community thrived not on talk, but on gossip. In the nearby village of Auchterdingle, the elders still made mention of the mule that had given birth three years after the Forty-Five. The offspring had been named Jesus, and its arrival had been taken as a sign that Bonnie Prince Charlie’s triumphant return was eminent.

That had been more than seventy years ago, and the miraculous mule was still frequently toasted. A potential scandal in the earl’s family would never, ever cease being a topic of speculation.

“If I am legitimate,” Ashton observed, “which I am not, then Mama and Papa were married at the time I was born. Mama would have been seventeen, a mere girl by English standards, and Papa not much older.”

“They were in love,” Ewan said, taking a seat at the estate desk. “And in Scotland, unlike England, a seventeen-year-old woman need not have her parents’ blessing to marry.”

Ewan made a magnificent picture behind the oak monstrosity, all dapper and blond, but a troubled, magnificent picture.

“I’ve been in love a time or two,” Ashton said. “Then I wake up with a sore head, and the affliction has passed.” He’d been infatuated countless times, until the infatuations had run together, into an abiding fondness for all of the ladies.

Alyssa’s lips twitched, an encouraging sign.

“Mama and Papa were passionately devoted,” Ewan went on. “Prior to your arrival—and prior their setting up a household out on Rothsay—they managed a quiet little wedding. By the time Mama’s family caught wind of her whereabouts, that household had three children. At that point, Uncle Arthur was unwell, cousin Hugh had gone to his reward, and Papa had become the heir apparent. He went from being an unsuitable Scottish upstart to a Border lord’s heir.”

A wealthy Border lord’s heir, and thus eligible in the eyes of the English side of the family.

Alyssa rose and perched on the arm of Ewan’s chair. They were a striking couple—both tall, well-favored, and fair, and their marriage had been a love match. Ashton hoped it still was, but this business of the succession had apparently put a strain on the relationship.

“Everybody was sure your papa would abandon his scandalous liaison and marry a proper Scotswoman,” Alyssa said, “one who’d bring wealth and standing to the union. Instead, after much argument with the old earl, your papa and your mama had public ceremony with her family in attendance. She was of age then even by English standards. I imagine her family was relieved, for who else would marry a woman ruined by a Scottish rogue?”

Such a romance belonged among Sir Walter Scott’s drivelings. “Why not reveal the earlier marriage before the public union began?” Why deny Ashton and his sisters legitimacy when it might have made a difference?

“Your mama’s family would have argued to keep you in England,” Alyssa said, “to be raised among the civilized English. She’d had you with her for several years, and she wasn’t about to give you up. Your father supported her decision. If you’d been in line for the title, the old earl would have sent you south without a qualm.”

The old earl had believed in currying favor with the English, a sensible, if unpopular, approach. A Scottish heir raised among the English would have had all the advantages of a medieval fostering, from a political perspective.

And might have received abominable treatment, even at the hands of his own relations.

“Uncle took much too long to die,” Ewan said. “I came along, the earlier marriage had not been revealed, and you were being raised as a by-blow, though in our parents’ household, not among English strangers. My legitimacy was unassailable, while yours was shrouded in secrecy and family squabbling. Had Alyssa not found Mama’s diary, we would have pensioned Gunna off to the Midlands and dismissed her maundering as fancy.”

“Unfind the diary, then.” Ashton loved his brother dearly, but a title sometimes deprived a man of common sense. Marriage records on Rothsay were likely to fall into the sea before anybody stumbled upon them.

“I’ll not unfind the diary,” Alyssa said, shoving away from her husband’s side. “There’s been enough dissembling and drama, and I won’t have my son’s inheritance questioned when some greedy cousin unearths church records or finds an old diary from the English side of the family years from now.”

The English were forever causing trouble, that was true enough.

“I thought you liked being the earl and countess.” Ewan and Alyssa excelled at being titled. They were gracious, generous, handsome, Scottish when it mattered, and diplomatic when an Englishman was underfoot. “You’ve made the earldom look like no burden a’tall, though I know that’s not so.”

Being the earl was work, and Ashton suspected being the countess was no less effort. The estate was huge, covering woodlands, pasture, land in cultivation, crofts, sheep ranges, lochs, streams, three villages, and—thank the generosity of the Almighty—a distillery. The earldom also involved rights pertaining to fishing, forestry, quarrying, land use, Border regulations, local administration, church functions… the demands were endless.

The English tenants expected all the blessings and perquisites of English law, the Scottish tenants wanted only Scottish traditions and legalities.

And yet, Ewan was popular among all of the local folk and the neighboring titles.

“You’ll make a fine earl,” Ewan said again, though he sounded as if he were reciting a prayer rather than expressing confidence in his older brother.

“You don’t know what you’re asking.” Ashton abandoned the sofa and spared a scowl for the portrait of their father over the mantel. “You are the earl, Ewan. You can foist the title off on me, but twenty years from now, when not a soul cares which of us is legitimate, you will still be his lordship, and I will still be ‘the by-blow.’”

“Then you will be the by-blow earl,” Ewan said, rising to slip an arm around Alyssa’s waist. “My wife needs peace and quiet. She needs freedom from worry and to know that her children will not be tormented with old secrets. I need for my wife to be happy, and thus you need to be the earl.”

Now there was some miserable logic.

“I need to get drunk, and this discussion is not over.” Ashton strode from the room, intent on making a dramatic exit. The door had slammed behind him with gratifying finality, when he thought of the most sensible course of all. He’d destroy the diary. How hard could that be?

He turned on his heel, prepared to announce this brilliant solution to his dunderheaded brother, but immediately outside the door, a sound caught his ear.

Sobbing. Loud, upset, female sobbing, and a man’s quieter, conciliatory tones. Alyssa wasn’t given to dramatics or manipulation, and she was in a delicate condition.

She was also genuinely miserable and upset, because of him.

Ashton leaned his forehead against the solid oak door. “I don’t want the bloody, fecking, miserable, sodding, bedamned, rubbishing, blighted title.” He wanted to hike into the village, flirt the tavern maids and old women into good spirits, jest with the village lads, and enjoy an argument with the blacksmith over a few wee drams.

Alyssa’s unhappiness crested higher, along with a few sharp words. Without warning, the door opened, and there she stood, her face tear-streaked. Ewan was at her side, his eyes full of pleading and worry.

A brother in trouble and a damsel in distress. Alyssa was also mad as hell, and at Ashton. His brother’s ire, he might have withstood, but Alyssa’s fury and disappointment were unendurable.

For an interminable moment, Ashton struggled against conscience and against the inevitable. When had being the bastard become so easy and comfortable? So integral to who he was?

Alyssa glowered at him, her lashes wet with tears.

“I’ll be the earl,” Ashton said, brushing his thumb over her damp cheek, “but I need one thing from the two of you.”

“Anything.” Ewan wrapped his arms about his wife. “We’ll support you in every possible way. You’ve only to tell us, and we’ll do it.”

That was not an earl talking, that was a besotted husband and a very worried prospective papa.

“You,”—Ashton tapped Alyssa’s nose—“will have sons. You will have nothing but sons, and they will be great, strapping bairnies whom I will spoil without limit, and one of those boys will be my heir. Understand?”

She nodded, a hint of a smile peeking through her tears.

“We’ll do our best,” Ewan said, cuddling his wife closer. “We’ll do our very best for you, Ashton. My word on it.”

“I’ll hold you to that.” Ashton closed the door, because the people he loved most in the whole world had presented such a picture of marital intimacy as to make a bachelor brother blush.

He took his walk to the village, all the while assuring himself that nothing needed to change. Ewan and Alyssa’s children would inherit the whole mess, Ewan would manage the earldom, and Ashton would be free to flirt with tavern maids and old women.

A fine compromise all around.

Except that, in less than three years, Alyssa had three babies, twins followed by a single birth. The infants were indeed great, strapping specimens and the births as easy as births could be… and every one of the children was female.

![]()

A bump-and-jostle of the criminal variety introduced Ashton Fenwick to his temporary salvation.

Fortunately, she was neither the little thief who so deftly dipped a hand into his pocket, nor the buxom decoy who feigned awkwardly colliding with him immediately thereafter, while the real pickpocket quietly dodged off into the Haymarket crowd.

Or tried to.

Ashton was exhausted from traveling hundreds of miles on horseback, and had barely noticed the thief’s touch amid the sights, noise, and stink of London’s bustling streets. In the instant after the bump, and before the jostle part of the proceedings—a game girl, from the looks of her paint and pallor—Ashton realized how London had welcomed him.

“Stop the wee lad in the cap!” he bellowed. “He’s nicked my purse!”

Five yards down the walkway, a woman darted into the path of the fleeing thief and faced off with him. A housewife from the looks of her. Plain brown cloak, simple straw hat, serviceable leather gloves rather than the cotton or lace variety.

Ashton had an abiding respect for the British housewife. If the nation had a backbone, she was it, not her yeoman or shopkeeping husband, whose primary purpose was keeping brewers in business and the wife in childbed.

The lady was nimble and sharp-eyed. When the child dodged left, so did she, and she never took her gaze off the miscreant.

“Give it up, Helen. You chose the wrong mark.” A hint of the north graced the woman’s inflection, also a hint of the finishing school. A lovely combination.

The child gazed up, though the woman was diminutive, then small shoulders squared. “You needn’t take on, Mrs. Bryce. I dint nick ’is purse.”

“You didn’t steal my purse,” Ashton said, letting the thief’s accomplice scurry away, “because I know better than to keep it where it can be stolen, but you got my lucky handkerchief.”

“Hit’s just a bleedin’ ’ankerchief,” the girl shot back. “Take it.” She withdrew Ashton’s bit of silk from inside her grubby coat, the white square a stark contrast to her dirty little fingers.

A crowd had gathered, because Londoners did not believe in allowing anybody privacy if a moment portended the smallest bit of drama. Some people looked affronted, but most appeared entertained by the thought of the authorities hauling the girl away.

“Helen, what have I told you about stealing?” Mrs. Bryce asked.

Helen’s hands went to skinny hips clad in boy’s trousers. “What ’ave I told you about starvin’, Mrs. B? Me and Sissy don’t care for it. ’E don’t need ’is lucky piece as much as me and Sissy do.”

Somebody in the crowd mentioned sending for a patroller from nearby Bow Street, and if one of those worthies arrived, the child’s fate would be sealed.

“We won’t settle this here,” Ashton said, taking the girl by one slender wrist. “Let’s repair to the Goose and have a civilized discussion.”

The girl’s eyes filled not with fear, but with utter terror. Ashton was big, male, and he was proposing to take the child away from the safety of public scrutiny. Well, she should be terrified.

“Mrs. Bryce,” Ashton went on, “if you’d accompany us, I’d appreciate it. Ashton Fenwick, at your service.”

“Matilda Bryce.” She sketched a curtsey. “Come peacefully, Helen. Unless you want to find yourself being examined by the magistrate tomorrow morning.”

The child was obviously inventorying options, looking for a moment to wrench free of Ashton’s grasp. As many spectators as had gathered, somebody would snabble her, and she’d be in Newgate by this time tomorrow.

“If you’d join us for a pint and plate, Mrs. Bryce,” Ashton said, “I’d be obliged. I realize a lady doesn’t dine with strangers, but the circumstances are—”

“She’s a landlady,” Helen said, stuffing Ashton’s treasure back inside her jacket. “Down around the corner, on Pastry Lane. Was once a bakery there. I could use a bite to eat.”

The child could use a year of good meals, for starters. Ashton hoped the thought of hot food would tempt the girl from more reckless choices, but he kept a snug hold of her wrist nonetheless.

“Helen offered to return your goods, sir,” Mrs. Bryce said. “Can’t you let it go at that?”

“Perhaps,” Ashton said. “But the longer we stand here debating, the more likely the authorities are to come along and take the child off to the halls of justice.”

“Move, Helen.” Mrs. Bryce seized the girl by the other wrist and started off in the direction of the nearest pub. “If the law gets hold of you, it’s transportation or worse. Heaven knows what will become of your Sissy then.”

Mention of the sister wilted the last of the child’s resistance, and Ashton was soon crossing the street while more or less holding hands with a small, grubby female.

Who still had his lucky handkerchief.

The Goose was a respectable establishment, and because the theater custom was in general a cut above London’s meanest denizens, the food might be better than passable. Ashton bought steak, potatoes, and a small pint for each of the ladies.

For himself, brandy. He was in London, prepared to take up residence at no less establishment than the Albany apartments. Titled lords ready to embark on the joys of the social Season drank brandy, or so Ewan claimed.

Besides, Ashton was hoarding his whisky for emergencies and celebrations, which this was not.

“Now,” he said, when the child had shoveled down an adult portion of food in mere minutes. “You, Miss Helen, need to work on your technique if you’re intent on a life of crime. Would you like some cobbler?”

Her eyes grew round while Mrs. Bryce wiped the child’s chin with a linen serviette. “Don’t encourage her. She’ll end up on the gallows at the rate she’s going. Do you want her death on your conscience?”

“Do you want her starvation on yours?”

Over the empty plate, the child’s gaze bounced between the adults on either side of the table. “About that cobbler?”

Ashton reached into the girl’s coat and withdrew his handkerchief, then passed it to Mrs. Bryce. “Wait here, child, if you want your cobbler.”

He went to the bar, placed an order for three cobblers, and kept his back to the tables while the kitchen fetched the food.

When they’d chosen their table, Mrs. Bryce had taken off her hat and gloves. Her hair was an unusual color, as if she’d used henna to put a reddish tint in blond hair, which made no sense. Few women would choose red hair over blond, but then, Ashton was in the south. Everything from the sunshine to the scent of the streets was different.

“Your cobbler, sir,” said the publican, putting a sack before Ashton. “We expect return of the plates in a day, if you please. Mrs. Bryce is always very good about that.”

The barkeeper was short, graying, and solid—not fat. His blue apron was clean and free of mending.

“Mrs. Bryce patronizes your establishment often?”

“We’re neighbors, across the alley and down a street, and her tenants frequently send out for their meals. She always sees to it we get our wares back. Haven’t seen her in a bit, or had an order from her lately. Please give her my regards.”

“She runs a good establishment?” Ashton asked.

“We hear nothing but compliments from her tenants. The place is very clean, very quiet, if you know what I mean. A widow can’t be too careful. She keeps out the rabble, which isn’t always a matter of who has coin, is it?”

Ashton had a very particular fondness for widows of discernment.

“True enough,” he said, putting a few coins on the bar and gathering up the cobblers. “My thanks for a good meal.”

A hearty meal. Not the refined delicacies Ashton had been expected to subsist on from the earldom’s fussy Italian chef.

Mrs. Bryce was dissuading Helen from licking an empty plate when Ashton rejoined the ladies.

“I have here three cobblers,” he said, setting the sack in the middle of the table. “I’m too full to enjoy my portion. Perhaps Helen’s sister would like it?”

Fine gray eyes studied him from across the table. Mrs. Bryce’s gaze was both direct and guarded, which made sense if she’d lost her husband. Widows were as vulnerable as the next woman, and yet, they had more freedom than any other class of female in Britain.

“Sissy loves her sweets,” Helen said, kicking her legs against the bench. “I’m right fond of a treat myself.”

Ashton slid onto the bench. “I’m fond of young ladies who take responsibility for their actions.”

Helen shot Mrs. Bryce a puzzled glance.

“He means, you stole his handkerchief, and now we must decide what’s to be done.” Mrs. Bryce folded up Ashton’s handkerchief and passed it to him.

Ashton set the cloth beside the cobblers. “What would you do, Helen, if somebody had stolen your lucky piece?”

“Ain’t got a lucky piece. If I had a lucky piece, maybe I wouldn’t be stealin’ for me supper.”

Ashton snatched off the girl’s cap, and ratty blond braids tumbled down.

The child ducked her head as if braids were a mark of shame. “Gimme back me ’at, you!”

“How do you feel right now?”

“I’m that mad at you,” Helen shot back. “You ’ad no right, and now everybody will know I’m a girl.”

Ashton passed over the hat. Helen jammed it back on her head and stuffed both braids into her cap before folding her arms across her skinny chest.

“I gave you back your hat. All better?”

“You know it ain’t. Damned Treacher saw me without me cap. Now I’ll have to cut me hair again and stay out of his middens for weeks.”

Mrs. Bryce watched this exchange, looking as if she was suppressing a smile. She had a full mouth, good bones, and a sunrise-on-summer-clouds complexion worthy of any countess. She was that puzzling creature, the woman who didn’t know she was attractive.

Or perhaps—more puzzling still—she didn’t care that she was attractive.

“So, wee Helen,” Ashton said, setting the empty plates out of the girl’s reach. “You’ve returned my handkerchief, and I’ve returned your cap. You still disrupted my day, gave me a bad start as I arrived in your fair city, and have inconvenienced Mrs. Bryce, who I gather is something of a friend. How will you make it right?”

The child scrunched up her nose and ceased kicking the bench. “I don’t have anything to give you. You could thrash me.”

From her perspective, that was preferable to being turned over to the authorities. Mrs. Bryce was no longer smiling, though.

“Then I’d have a smarting hand,” Ashton said, “and more delay from my appointed rounds, because you would require a good deal of thrashing. Fortunately for us both, you are a lady, and a gentleman never raises his voice or his hand to a lady.”

Now the looks Helen aimed at Mrs. Bryce were worried, as if Ashton had started babbling in tongues or speaking treason.

“Your papa wasn’t a gentleman,” Mrs. Bryce said gently. “We mustn’t speak ill of the dead, but Mr. Fenwick is telling you the truth. Gentlemen are to protect ladies, not beat them. In theory.”

“I don’t know what a theory is, ma’am. Can I ’ave my cobbler yet?”

“May I,” Mrs. Bryce replied. “I think Mr. Fenwick expects an apology, Helen, and you owe him one.”

“I’m sorry I nicked your lucky piece. If I’d known it was a lucky piece, and not just fancy linen, I might not ’ave nicked it. Next time, keep your purse in your right-hand pocket, and nobody will be stealin’ your lucky piece.”

Helen clearly didn’t realize this earnest advice was in no way helpful.

The comforts of the Albany awaited, and those comforts had been sufficient for ducal heirs, nabobs, and Byron himself. Once Ashton stepped over the threshold of that establishment, he declared himself the Earl of Kilkenney in new and irrevocable ways.

He’d rather be enjoying a plain meal at the Goose, and getting lessons in street sense from a half-pint thief.

“As it happens, I’m glad you didn’t get my purse, because I’m newly arrived to Town this very day, and to be penniless in London, as you know, is a precarious existence.”

“Perilous,” Mrs. Bryce translated. “Dangerous.”

“Not if you know who your mates are and are quick on your feet,” Helen said—more misguided instruction. She was a female without protection or means. Odds were, sooner or later, the London streets would be the death of her.

“You have nonetheless taken up a good deal of my time when my day was already too busy,” Ashton said. “I need to establish myself at suitable lodgings. I need to hire a tiger for my conveyance. I need to get my bearings in anticipation of taking up responsibilities for the social Season.”

Not only a busy day, but also a damned depressing one.

“You need a home,” Mrs. Bryce said, and she wasn’t translating for Helen. “Or a temporary address to serve as your home.”

Her gaze turned appraising, though not in any intimate sense. The tilt of her head said she was evaluating Ashton as a lodger, not a lover. A novel experience for him, and a bit unnerving.

His attire was that of the stable master he’d been for years before he’d become afflicted with a title. Decent, if plain, riding jacket. Good quality, though his sleeve had been mended at the elbow. His linen was unstarched but clean enough for a man who’d been traveling, and a gold watch chain winked across his middle.

“What is your business in London, Mr. Fenwick?” Mrs. Bryce asked.

He was here for one purpose—to find a woman willing to be his countess. She’d have to comport herself like a faithful wife until at least two healthy male children had appeared. Not a complicated assignment, and the lady’s compensation would be a lifetime of ease and a title.

Ashton had had three years to reconcile himself to such an arrangement, three years during which he’d tried to find the compromise—the woman he could adore and marry, who might adore him a little bit too—but she hadn’t presented herself.

Though three wee nieces had arrived.

“My excursion to the capital is primarily social,” Ashton said. “I’m renewing acquaintances with a few friends and tending to business while the weather is fair. I’ll return north in the summer.”

And be damned glad to do so. According to Ewan, house parties followed the social Season, and rather than hunting grouse, Ashton could pass his summer with further rounds of countess hunting.

He could take up that apartment at the Albany some other day. Next week would do.

Or the week after.

A voice in Ashton’s head said he was putting off the inevitable, retreating when he ought to be marching forward. Another voice said Mrs. Bryce would not consider offering a strange man lodgings unless she needed a lodger desperately.

“As it happens,” Mrs. Bryce said, “I have an apartment available. A sitting room and bedroom, with antechamber, and kitchen privileges. Breakfast, tea, and candles are included, and your rooms will be cleaned twice weekly, Tuesday and Friday. Bad behavior or excessive noise is grounds for eviction, and if you sing or play a musical instrument, you will do so only at decent hours. Coal is extra, payable by the week.”

“Mrs. Bryce makes the best porridge,” Helen added. “She puts cream on it if it’s too hot.”

Don’t put off what must be done. Don’t shirk your duty.

“What is your direction?” Ashton asked.

“Pastry Lane is around the corner and halfway down the street,” Mrs. Bryce said. “The rooms are quiet, clean, and unpretentious, but suitable for entertaining such callers as a gentleman might properly have.”

No game girls, in other words.

“There’s a garden,” Helen offered. “Big enough for Mrs. Bryce’s herbs, but not big enough for a dog. She has a cat.”

Mrs. Bryce also, apparently, had something of a champion in Helen.

The child was skinny, but not starving. When truly deprived of food for a long period, the body lost the ability to handle a meal of steak and potatoes washed down by a small pint of ale. Helen’s diet might be spare and irregular, but Mrs. Bryce’s porridge figured on the menu often enough to keep body and soul together.

“I like cats,” Ashton said. “What about a mews?”

“No mews, I’m afraid,” Mrs. Bryce said, brushing a hand over the handkerchief on the table. “If you need a mews, I can suggest Mrs. Grimbly, off of Bow Street, though you must provide your own groom.”

The fingers stroking over Ashton’s handkerchief were slightly red, the back of Mrs. Bryce’s hand freckled. No rings, and a pale scar ran from wrist to thumb.

Not the hands of a countess, though, to Ashton, beautiful in their way.

“I can stable my horses elsewhere,” Ashton said. “My brother is more familiar with London than I am and recommended an establishment he and his friends use. What do you charge?”

She named a figure, neither cheap nor exorbitant, though her focus on the handkerchief had become fixed. The cuff of her cloak was fraying, her straw hat was the lowliest millinery short of Helen’s battered cap.

Mrs. Bryce was in need of coin, while Ashton was in need of peace and quiet. The social Season hadn’t yet begun, and a week or two of reconnaissance was simply the act of a prudent man—or a reluctant earl.

“Mrs. Bryce bakes her own bread,” Helen said. “And she serves it with butter and jam.”

“May we start with a two-week lease?” Ashton asked. “I am new to London, and a trial period makes sense for all parties.”

“That will be acceptable, though I’ll want the rent for both weeks in advance with an allowance for coal.”

Ashton extended his hand across the table. “Mrs. Bryce, we have a bargain.”

Chapter Two

The angel of bad fortune had plagued Matilda Bryce for the past nine years, but since January the wretch had been perched on her very doorstep. Her last tenant had fled to the Continent with three months’ rent and coal fees owing, and he’d kept his apartment roasting.

No suitable replacement had appeared even as London’s ranks of single gentlemen had swelled with spring’s approach. Ashton Fenwick wasn’t suitable either, but needs must when the devil taxed every window and bar of soap a woman owned.

Mr. Fenwick’s nails were clean, not that clean nails signified anything. He was handsome, too, and that was the problem. Not in a pretty, Bond Street way, but in the robust, muscular manner of the countryman. Dark hair and dark eyes suggested Celtic ancestry, and for all his brawn, his manners were fine.

In fancy ballroom attire, he’d turn every head, which was the last reaction Matilda wanted her lodgers to inspire.

“About the cobbler?” Helen asked as Matilda withdrew her fingers from Mr. Fenwick’s callused grip.

“Mrs. Bryce and I are having a wee business negotiation, child. We’ll get to your cobbler.”

Helen sighed gustily, despite having had a brush with disaster. The girl had no idea how lucky she’d been to pick Mr. Fenwick’s pocket, rather than that of a less tolerant citizen.

“If I’m to rent from you,” Mr. Fenwick said, “I’ll need a servant of sorts, somebody to let my groom know when I need my horse, to fetch my evening meal from the chophouse, to polish my boots. Have you a boot boy or underfootman who can serve in that capacity?”

Well, drat and perdition. If it wasn’t a gentleman’s horses Matilda couldn’t accommodate, it was his boots.

“I have only a maid of all work, though your quarters provide room for a servant in the attics, should you wish to hire one.”

Mr. Fenwick’s gaze roamed the interior of the Goose, a typical London public house. The ceiling was low and the beams exposed. The plank floor was uneven and centuries of smoke had turned the rafters black.

The patrons at the Goose came from many walks of life: the swells and dandies dangling after the actresses, the working folk happy to end their day with a pint, and the actresses and shopgirls who needed a safe place to take an occasional meal.

The highest and mightiest of polite society, however, did not frequent the Goose, and thus Matilda could tarry with Mr. Fenwick and try to haggle him back under her roof.

“I’m sure we can send your boots out,” she said, “or my maid can have a go at them.” To do a proper job on a gentleman’s boots was time-consuming. Matilda did not flatter herself that she had the skill, or she’d gladly take it on.

“I can be your boot boy,” Helen said. “Me da taught me how to shine boots, and I’m ever so fast if you want a note delivered or a meat pie brought ’round.”

“Helen, you’re not a boot boy,” Matilda said. “You’re not a boy at all.”

“But you are a thief,” Mr. Fenwick said, his tone appraising. “If an incompetent one.”

“I told you,” Helen retorted. “If you’d carried your purse where a purse ought to go, I’d have nicked it clean and proper. If I wasn’t a damned good cutpurse, me da would have beat me lights out. He told me so himself.”

At the bar, Mr. Treacher’s rag stopped its rhythmic polishing. One of the tavern maids slanted a glance in Helen’s direction, and Matilda had all she could do not to slap her hand over the child’s mouth.

“If you think I’ll put a serving of cobbler in front of you to prevent you from crying your own doom,” Mr. Fenwick said, “think again, my girl. English law lists more than two hundred hanging offenses, theft among them. A little thing like you would take a very long time to die on the end of a rope.”

For once, Helen looked daunted.

Thank God.

Mr. Fenwick was tall, broad-shouldered, and exactly the sort of man Matilda ought not to be giving a key to her house. She had a separate lock on her own rooms, but the hardware was old, and Mr. Fenwick was in his prime. She’d put him not much past thirty, with a history of manual labor such as a steward or wealthy yeoman might undertake.

Gentlemanly manual labor, which ought to be a contradiction in terms.

His speech was educated, but accented—Borders, or perhaps Cumberland—and his attire suggested he knew better than to advertise his means on the open road. That he wanted only two weeks’ lodging was a shame. He was from out of town, which was good, and he had dealt kindly with Helen so far—which was very good.

“Have you ever ridden a horse?” Mr. Fenwick asked Helen. “The truth, or no cobbler.”

“How will you know if I’m lying?”

“You’ll be dead,” he replied, opening the sack of cobbler so the scent of apples and cinnamon wafted about the table. “My horse is an enormous specimen named Destrier. If you don’t know what you’re about, he’ll toss you to the ground like so much dirty linen.”

“I could lead him.”

“You’re considering hiring Helen as your lackey?” Matilda interjected. The Goose made a very fine cobbler. She’d forgotten that.

“For two weeks,” Mr. Fenwick said. “My needs are modest, Helen knows the neighborhood, and she can use the wage.”

“You’d pay me?”

Helen’s consternation tore at Matilda’s heart and woke up her distrust. “I cannot condone an arrangement which puts a little girl into the direct employ of a man about whom I know next to nothing.” Terrible things happened to children loose on London’s streets. Things Matilda could not have comprehended at Helen’s age, things Helen had probably witnessed firsthand.

Mr. Fenwick put a serving of cobbler down before Matilda. “We are strangers, true. What would you like to know about me, Mrs. Bryce?”

The second serving he set before Helen, who at least recalled to put her linen back on her lap before she picked up her fork. Matilda tried to impart some manners on the rare occasions when Helen came by for a meal, but etiquette stood no chance against a ravenous belly.

Matilda took a bite of spicy, fruity delight while she considered Mr. Fenwick’s question. The cobbler needed to be a bit warmer and slathered in cream to be truly exquisite, but it was very good nonetheless.

“I want to know that you are honorable,” Matilda said. “You appear without character references, so I don’t see how we’re to establish your trustworthiness. I can demand your coin before you set foot in my house, but Helen’s safety is less easily guarded.”

“I love cobbler,” Helen said. “He doesn’t have to pay me. Just let me eat cobbler every day.”

“Wee Helen, if I feed you cobbler, how will you buy a new cap when somebody snatches that fine bit of millinery from your head?”

“I’ll snatch it back.”

Mr. Fenwick plucked the cap from the girl’s head again, and this time she smiled. “You’re very quick, sir. I could show you how to pick pockets, if you like.”

He plopped the hat down on her head. “Wages, my child. Cash in hand, coin of the realm. That’s how you want to be paid. All else is dross, and be mindful of Mrs. Bryce’s example. I’m to pay her first, and when she’s seen my coin, then and only then will I have what I need in return.”

Helen was perilously pretty when she smiled. Better for her if she were homely and pockmarked. In a very few years, her beauty would become a liability, unless Matilda could make a parlor maid, or a—

Inspiration struck. “What if I raised your rent to cover Helen’s services?” Matilda asked. “She’d be answerable to me, but available to fetch your horse, tend your boots, and buy your meals?”

“You’d give her a bed in the attics?” Mr. Fenwick asked as Helen slurped up her cobbler. “Breakfast, laundry services?”

“Mrs. B can’t do my laundry ’cause these are my only clothes. I stole ’em off a clothesline, and they still fit me.”

“She’s determined to get herself hanged,” Matilda muttered. “I try, but her older sister undermines my efforts.”

Helen’s head came up. “Don’t you say nuffink bad about my Sissy.”

“If today is any example,” Mr. Fenwick said, “Sissy is no better at crime than you are, and that is a compliment. How much to hire Helen as my general factotum?”

The arrangement was unusual. Little girls didn’t sport about in trousers and work for gentleman lodgers. And yet, those trousers had probably yielded Helen more security and well-being than Matilda’s occasional bowl of porridge had.

Matilda named a sum—a fortune by Helen’s standards, a pittance compared to what many earned in service to a great house.

“Done,” Mr. Fenwick said, rising. “Helen, you’ll need a name I can call you in public. Hector, I think. It suits you. You will take this cobbler to your sister, explain where she can find you for the next two weeks and that you’ll be biding in Mrs. Bryce’s house. You will report to my quarters two hours from now, and I’ll show you where I’m stabling my cattle.”

“How will I know it’s two hours?”

“You listen to the bells,” Matilda said, for she’d had to figure that out when she’d sold her last watch. “The cathedral bells just chimed a quarter past the hour, so you listen for seven more chimes. By the eighth tolling of the bells, you’d best be at my house.”

Helen counted off on her fingers. “Eight times. Can I take Sissy her cobbler now?”

May I. Matilda saved the grammar instruction for another day.

“Off with you,” Mr. Fenwick said, gently tucking the girl’s braids back up under her cap. “Two hours, or you’ll be sacked before you begin.”

Helen—miraculous to relate—stood still while Mr. Fenwick fussed with her hair. She then snatched the sack holding the last cobbler and darted off.

“She is quick,” he said. “You were quicker. Why did you stop her?”

By preventing Helen’s flight, Matilda had left the child open to the risk of incarceration, or worse.

“Instinct, I suppose. If somebody doesn’t intervene with her, she won’t last much longer. I met her when she tried to break into my house last year. A lame, drowned rat would have been less pathetic, and her sister means her no good.”

Mr. Fenwick rose. “Will we see her again?”

He was bit and fit. Helen must have been desperate to think she could steal from this man with impunity.

“I honestly don’t know. I hope so. Shall I show you to your lodging?”

“I’d like that.” He offered his hand, as if Matilda hadn’t been getting up off her own backside unassisted for years. “I’m mostly in need of a bath and a nap. If you’ll offer me those, I’ll be your devoted slave for the next two weeks.”

He wrapped Matilda’s hand around a very muscular arm, as if she were a proper lady. He had a mama, then, or sisters. Possibly a wife.

The thought shouldn’t bother her.

“We haven’t far to go,” she said as they emerged from the Goose. “I assume you have baggage?”

“Aye, and once I have your direction, I’ll see to having a trunk delivered. Can you recommend a decent chophouse in the area?”

He made pleasant small talk with her for the short walk to Pastry Lane, and Matilda had the first inkling that Ashton Fenwick might be trouble. He was a considerate escort, matching his steps to hers, always taking the outside lest some passing coach splash her skirts.

He tipped his hat to the women who took notice of him.

He bore a faint fragrance of bayberry shaving soap, and he tossed a coin to the crossing sweeper.

Any one of these observations would not have alarmed Matilda, but the longer she walked at Mr. Fenwick’s side, the more convinced she became that he was a gentleman in truth. Probably a wealthy gentleman, given how circumspect the Scots were when it came to displaying their riches.

“If I needed to stay on a bit longer than two weeks, could that be arranged?” he asked as Matilda led him up the front steps to her house.

The last person she ought to accept as a lodger was a wealthy gentleman about whom she knew little and from whom she had no references.

“Why don’t we see how you like the accommodations?” she replied. “They might not be to your taste.”

“The accommodations will be entirely acceptable,” he said, pushing the door open and waiting for Matilda to precede him through.

The manners were a subtle reminder of all she’d run from, all she’d left behind, and yet to him, they were the most casual exercise of consideration.

She showed him the rooms—clean, as she’d said, comfortable, unpretentious. The bed was huge, being an antique from when the house had been a grander establishment. The windows overlooked her tiny garden rather than the noisy street.

“I’ll be more than happy here,” he said, tossing his hat onto the hook above the sideboard. “If you don’t mind, I’ll have that nap while I wait for my general factotum to report for duty. I’m very glad we met, Mrs. Bryce. You’re the answer to my prayers.”

He took her hand and bowed over it, which would have been a fine, if somewhat theatrical, gesture.

The damned man smiled, though, not extravagantly, mostly with a pair of dark brown eyes. He gazed down at Matilda as if they shared some delightful secret, and that was ludicrous.

“I’ll get the maid started on your bathwater,” she said. “By the time you’ve had your nap, we should have enough heated in the laundry to accommodate you.”

She withdrew quickly and took her secrets—not a one of which was delightful—with her.

![]()

“I’m not sure I understand, my lord.” Cherbourne’s brows were knit in puzzlement, though Ashton’s valet was a bright man. He was conversant in six languages that Ashton knew of, as well as the deferential-servant dialect of the King’s English. His attire was the pattern card of a proper gentleman’s gentleman, and his graying fringe of hair was precisely trimmed every seven days.

Ashton had inherited him from Ewan, and in some ways, Cherbourne was a worse curse than the title.

“The idea is simple,” Ashton said. “I’ll not be staying here for at least two weeks. Set up the rooms with my needs in mind, get to know the neighboring households, find us the best chophouses and coffee shops. I’ll come by periodically when I need the horses or to collect my mail.”

“But, my lord, who will starch your cravats? Who will polish your boots? Who will shave you?”

Helen, braids tucked under her cap, sat on one of the many trunks stacked in the middle of the airy parlor and watched this exchange as if it were a panto down at the market.

“Cherbourne, I value your services, but please recall that for most of my adult life nobody starched my cravats, I polished my boots, and I even managed to shave myself occasionally. You are to have a holiday.”

And so am I.

The valet looked around as if Ashton were about to abandon him to the stink of Newgate jail rather than to twenty-foot plaster ceilings, enormous sparkling windows, and imported furnishings.

Ashton well knew that Cherbourne’s distress was not with a two-week holiday, but rather, over the more pressing question: What shall I tell your brother?

“I’ll send Hector around at least once a day to see if you have messages for me,” Ashton said, for the girl needed to be kept out of trouble somehow. “I need time to reconnoiter before polite society starts gawking at me.”

Cherbourne took out a handkerchief and mopped his brow. “I must in all honesty tell you, my lord, this is very irregular. You’ll have no one to brush off your coats, lay out your clothes, oversee the laundresses, trim your hair. I cannot like this idea at all.”

Ashton loved the idea. Wished he’d thought of it three years ago when Ewan had dragged him south to make the acquaintance of Fat George and the sartorial thieves on Bond Street.

“I’ll manage, but I’d appreciate it if you’d not inform my family of my decision.”

Cherbourne took inordinate care refolding the handkerchief. “My lord, I would not presume to correspond with persons so far above my station.”

Helen’s snort was worthy of a dowager duchess.

“You would presume to correspond with my butler,” Ashton said, “who would have a word with the housekeeper, who might let something slip to the nursery maid, who’d mention to Lady Alyssa that you’d sent word up from London that the earl was acting peculiar again. Every time I took you with me to see friends in Cumberland, you sent off more dispatches than Wellington on the eve of battle.”

Cherbourne straightened his shoulders, though nothing would make him an impressive figure. He was a small, dapper, balding little mole of a man, right down to the squinty expression and buckteeth.

“A gentleman’s gentleman is allowed proper concern for his employer,” Cherbourne replied. “I consider it part of my role to describe my experiences of the wider world to the staff not fortunate enough to travel. They share my concern for you, my lord.”

“I’m an ungrateful wretch, is that it?” This discussion was overdue, and it should have been uncomfortable.

Starched cravats were uncomfortable.

“Your lordship is tired from the journey,” Cherbourne said. “London can be overwhelming, I know. Your brother took some while to adjust to the demands made upon a titled gentleman here in the capital, but I’m sure, in time, you too will move effortlessly among your peers.”

For three years, Ashton had been Cherbourne’s work in progress, his Galatea, a block of stone to be fashioned into a titled paragon.

Helen shot Ashton a look, as if he’d missed his lines.

“Cherbourne, I will write you a glowing character, if that’s what you want. In London, you should have no trouble finding employment worthy of your skills. Here’s what I want: No more subtle laments, sermons, or scolds. I pay your salary, you give me your loyalty and your service. Me, not Ewan, not Lady Alyssa, not your cronies among the staff. You don’t tattle on me as if I’m a naughty underfootman. You don’t presume to criticize my need for a little privacy. You are the valet, I am the earl. Keep to your place or find another position.”

Three years ago, Ashton could not have carried out the threats he was making.

“I… but…”

“Or I can write you a modest character, confirming dates of employment and competence only.”

“My lord, you cannot… that is… This is most irreg—”

Helen drummed her heels against the side of the trunk.

“No character at all,” Ashton said. “Out on your ear. I’ll save some coin and get shut of that most disgusting exponent of dishonor, a spy under my own roof. I can shave myself. Did it for years.”

“You should apologize, Mr. Chairbug,” Helen said. “Turns ’em up sweet, and you might get a cobbler.”

“Do we understand each other?” Ashton asked.

“Say yes,” Helen chirped. “I don’t think you’ll get a cobbler, though.”

“We understand each other, sir.”

“Delightful. That took only half an hour I shouldn’t have had to waste. Hector, let’s be off. Cherbourne has much to do, even if he isn’t sending hourly missives to people who have no business meddling in my life.”

Helen hopped off the trunk and darted to the door. She’d shown up at Mrs. Bryce’s exactly on time and peppered Ashton with questions the whole way to the Albany. Her opinions were marked, original, and incessant.

And, bless the child, not a one of those opinions came with a “my lord” attached.

“So you’re a nob?” she asked as they made their way down the steps.

“I’m Mr. Ashton Fenwick.”

She gazed up at him. “Mrs. Bryce don’t hold with lying. I’m fair warning you, because I’m your general tote ’em, though you haven’t given me nuffink to tote yet. If I take your coin—and your cobbler—then I should look out for you.”

“You will carry my confidences. My name is Ashton Fenwick. Whatever else I might be is of no moment, and you won’t mention it.”

Helen hopped down the stairs. “Right, guv, and I’m the Queen of the Fairies. Mention that all you please, especially to old Sissy when she gets in a taking about one of her flats.”

Flats were the men who hired prostitutes. That Helen knew of such goings-on wasn’t wrong, because what she grasped she could take steps to protect herself from.

That she needed to protect herself from her sister’s customers was very wrong, indeed.

“Time to introduce you to my horse,” Ashton said. “Then you’re to show me where we can find some supper.”

“I’ve never met a horse before. Met plenty of horses’ arses.”

“So have I.”

“Mrs. Bryce doesn’t like bad language.”

“I do, when it’s done properly. Don’t tell her I said that.”

Helen stopped at the foot of the steps. “Cost you a cobbler.”

Ashton continued out into the early evening sunshine. “No deal. Mrs. Bryce will hear my bad language herself if the situation arises where I’m inspired to express myself colorfully. You will not comment on my behavior before others lest I turn you off without a character.”

“What’s a character?”

“A reference. A written testament to your competence and ability.”

Helen skipped along at his side as he made his way back to the mews, and damned if the child hadn’t the knack of skipping like a boy.

“Can’t use no written character if nobody can read it. Only nobs and reformers can read. Parsons too, but they’re all reformers. Mrs. Bryce can read.”

“Get Mrs. Bryce to teach you to read, Helen. It’s not that difficult once you learn the letters.”

“I know my name. H-E-L-E-N. How many letters are there?”

“Twenty-six.”

“Twenty-two to go. That’s a lot. If you teach me one a day for a fortnight, I’ll still have eight left.”

“You can do sums, but you don’t know your letters?”

“Sums is money, guv. I know all about sums.”

The introduction to Dusty—Destrier in formal company—went well. The horse was a good soul, patient, happy to please, and tolerant of barn cats, reluctant earls, and stable boys who whistled off-key.

“He’s big,” Helen said, brushing a hand down the gelding’s long nose. “He’s big as an elephant.”

“Not quite. I was encouraged to find a more refined mount, but he suits me.” Ewan all but groaned every time Ashton climbed into Dusty’s saddle, but the horse was proof that Ashton hadn’t always been the earl, and thus as precious as a holy relic.

Helen proposed dinner at the Unicorn, based on her scientific comparison of its middens and clientele with those of its competition. Her judgment was vindicated by the fare. Hot, hearty, plentiful, and plain—Ashton’s favorite kind of meal.

He used the dinner hour to acquaint her with the letters d, for Destrier, and b, for Mrs. Bryce, by drawing with his fork in her gravy.

The girl could eat like a horse, but had some manners, probably as a result of Mrs. Bryce’s ceaseless efforts.

“I should take this last bit to Sissy,” Helen said. “She’ll be out and about now. She starts by the theaters in case any of the gents want a go before the performances. They usually do, but there’s more business later.”

Helen’s blasé recitation made Ashton’s dinner sit uneasily in his belly.

“If any of those gents ever make you feel awkward, you tear off. Don’t be nice, don’t smile, don’t ignore the look they’re giving you. Don’t give them any warning you’re getting ready to bolt, Helen. You run like hell and scream bloody murder. Up a drainpipe, down a coal chute, but run.”

Helen licked the last of the butter from her knife. “Sissy says the same thing. I’ve pulled a bunk a time or two. They can’t catch me.”

Not yet, they couldn’t. When Helen was hampered by skirts, they might.

“Here,” Ashton said, holding out a few coins to Helen. “Buy your Sissy some food, and then it’s back to Mrs. Bryce’s with you. A general factotum who’s not at her post isn’t worth her hire.”

Helen looked at the coins in Ashton’s hand, then up at his face, a question in her eyes.

“I’m not looking to become one of your sister’s flats. This is a vale, a little extra coin for starting off your job on the right foot. Keep up the good work, and you might earn a bit more.”

The money was gone, and Ashton hadn’t felt Helen’s fingers touch his palm.

“Good evenin’ to you, guv. I’ll tell Sissy I found the blunt in the street.”

The child apparently never walked. She skipped, ran, strutted, scampered, and fidgeted, much as Ashton had at her age.

He’d been the bastard firstborn, perhaps subject to sterner discipline than the heir, but he’d never had to worry about his safety, not as Helen had to.

He was still pondering that injustice as he neared his temporary lodgings. Pastry Lane was what an Edinburger would call a wynd, more of a courtyard at the end of a covered passage than a proper lane. The houses on either side hung out over the passage, though they didn’t quite meet. No conveyance would fit down Pastry Lane, and little sunshine leaked onto the worn cobbles.

Keeping intruders out would be easy, as would keeping an eye on the neighbors. Mrs. Bryce’s abode opened onto the small courtyard where the lane ended, a space shared with four neighboring houses.

Ashton was across the main thoroughfare one street up from Pastry Lane when he saw a familiar brown cloak and straw hat bobbing along the walkway twenty yards ahead of him.

Mrs. Bryce, apparently returning from the last shopping errand of the day. She carried a parcel under her arm and made her way briskly in the direction of home.

Ashton watched for a moment, appreciating the energy in her stride and the good fortune that had put them in each other’s path. Two weeks of hot porridge, simple meals, and freedom from servants, sycophants, and meddling family would be heaven.

He was about to cross the street and offer the lady his escort when he became aware of another man trailing Mrs. Bryce about thirty feet back. Close enough to keep her in sight, far enough away to avoid detection.

He wore the uniform of the man of business. Plain brown breeches and jacket, slightly worn, no walking stick or other distinguishing accoutrements, not even a hat. When Mrs. Bryce stopped to chat with an older woman leading a child by the hand, the man following examined the wares on display at a potter’s shop.

Mrs. Bryce bid the other woman farewell and went on her way, and the man behind resumed walking as well.

Ashton was across the street in long strides and kept on moving until, as if in an effort to overtake Mrs. Bryce, he bumped the package from her grasp.

He stopped, tipped his hat, and picked up the parcel. “You’re being followed,” he said, beaming to all appearances sheepishly. “Let me carry your package, and please accept my escort.”

Those fine gray eyes took a casual inventory of the surroundings. “Thank you, sir. I’m sure there’s no damage.”

Ashton winged his arm, and bless the woman for her common sense, she took it and let him lead her away from Pastry Lane.

Chapter Three

If Matilda believed in one eternal verity, one immutable law of nature that would hold true down through the millennia, it was that Men Were Dreadful. Not all men, not all the time, which meant a woman had to be that much more vigilant to dodge the worst transgressors.

But most men, most of the time, were dreadful. They displayed petty dreadfulness, such as the tenant who was too lazy to carry his dirty dishes downstairs even on his way out for a morning stroll. He made more work for Pippa, the maid, and wasted her time. Was any disrespect quite as purely rotten as wasting a busy person’s time?

A tenant who nipped off to France without paying three months’ rent was more dreadful still and left Matilda to wonder if that tenant would have treated a landlord with the same disregard as a landlady.

No, he would not.

In a league of their own were men who arranged a daughter’s future so she was bound to an ungrateful tyrant, one who held her accountable for matters even the Church agreed were the exclusive province of the Almighty.

Worse yet were the men whose ungovernable urges meant their wives died in childbed, or suffered regular violence for no reason.

Dreadful, dreadful-er, and dreadful-est, as Helen would have said.

Matilda could have fashioned her own version of the circles of hell based on the transgressions which the male gender considered its casual right, simply because that gender had more muscles and less sophisticated procreative apparatus.

She was at a complete loss when Mr. Fenwick appeared at her side, her parcel in his hands, and a warning on his lips. She took his arm, very much against her inclinations. A woman who could work eighteen hours every day and still stay awake through Sunday services most weeks was capable of walking down the street unassisted.

And yet, if Matilda was being followed, she was in Ashton Fenwick’s debt. “Can you describe the person following me?” she asked quietly.

“He’s dressed to blend in,” Mr. Fenwick replied while, to all appearances, wandering along on a pleasant spring evening. “Plain brown clothes, no hat, no gloves. Medium height, medium age, medium everything. The perfect invisible man. Let’s have a cup of coffee, shall we?”

“I don’t care for it.”

“Neither do I.”

Mr. Fenwick was adept at eluding pursuit. One moment, Matilda was walking down the street beside him, the next, she was inside a coffee and pastry shop more genteel than most around Haymarket proper.

“I’ll order for us,” Mr. Fenwick said. “Chocolate for you?”

Matilda loved chocolate, but seldom took the time or spent the coin to indulge. The shop wasn’t crowded, the dinner hour having arrived, but neither was it deserted. Clerks and shopgirls, housewives and older men occupied scattered tables. A young waiter in a bib apron moved about, cleaning up dirty dishes and scrubbing tables.

“Chocolate would be delightful.” The scent of the place was heavenly, full of baking spices, with the aromas of coffee, chocolate, and black tea blending as well.

“That table,” Mr. Fenwick said, passing Matilda her parcel. “The one in the corner, so we can both sit with our backs to a wall.”

Matilda did as he suggested, because his reasoning made sense. She kept an eye on the street beyond the windows and saw, bobbing among the crowd, a bare-headed man of middle years and middle height saunter past, his attire a plain brown.

Mr. Fenwick came to the table and took the seat facing the street, while Matilda faced across the dining area. He set a plate bearing three scones in the middle of the table.

“You bought scones? Cinnamon scones? Fresh cinnamon scones?”

“I’m from the north. We appreciate a fresh scone at any hour.”

Men bearing cinnamon scones were worth tolerating, at least temporarily. Matilda set her hat on the bench beside her and removed her gloves. The waiter brought over butter and jam, and before Matilda had properly buttered her scone, the chocolate arrived.

“If you’re trying to bribe your way into my good graces, it won’t work,” she said. “The attempt is delightful, nonetheless.”

“I’m trying to prevent somebody from following you home,” Mr. Fenwick said, holding his cup of chocolate beneath his nose.

That nose was in proportion to the rest of him and had been broken at least once.

“You needn’t trouble yourself further, Mr. Fenwick. I saw your medium-height, brown-garbed man go by when you placed our order. That was Aloysius Aberfeldy. He’s a man in love, and he frequently follows me.”

Mr. Fenwick set his chocolate down untasted. “Do you enjoy his attentions?”

“Aloysius isn’t in love with me. He’s in love with my house. These scones are marvelous.” Fresh, warm, light as a wish, and dusted with sugar. Matilda promised herself she’d bake a batch on the next rainy day.

“I am quite fond of my horse,” Mr. Fenwick said, sipping his chocolate, “but in love? Surely you indulge in hyperbole.”

Mr. Fenwick’s manners weren’t so much dainty as Continental. He savored his food, tore off one bite of scone at a time, and enjoyed it.

He’d probably be a good kisser, which signified exactly nothing.

“I am indulging in euphemism,” Matilda said, dipping a corner of her scone into her chocolate. “Mr. Aberfeldy covets my house. If he married me, my house would become his house, absent convoluted trusts and vigilant trustees. Even with those in place, my dear husband could have me committed at his whim to one of those very quiet estates with very high walls tucked very far in the country. Then he could do with the house as he saw fit.”

Mr. Fenwick eschewed butter on his scone, for which Helen would have castigated him at length.

“You have a flare for the dramatic, Mrs. Bryce.”

Matilda paused in the middle of what constituted a small orgy, for Mr. Fenwick was humoring her, and that transgression required immediate correction.

“Doesn’t it strike you as odd, sir, that the Almighty, in His perfect wisdom, has given us no commandment against coveting our neighbor’s husband?”

Mr. Fenwick sat straighter. “There’s the one about adultery.”

“Irrelevant,” Matilda replied. “Adultery contemplates a man’s bad behavior again, with a wife not his own, as if the Deity wanted to emphasize a point through repetition of the obvious, perhaps. None of the commandments address the possibility of a woman straying onto some other lady’s preserves. Why do you suppose that is?”

“I’m sure you will enlighten me.”

“I will offer you my theory. Your chocolate is getting cold.”

“While you are warming to your topic. You should have chocolate more often.”

“Perhaps I should. In any case, I think the Creator knew that after a woman has had a glimpse of the wonders of holy matrimony, she will have no inclination to cavort with anybody else’s husband.”

Mr. Fenwick chewed his scone contemplatively. “People remarry.”

“Men remarry so their children have a mother, or their household has an unpaid drudge who’s also required by the church and the law to grant her husband other favors. Women remarry lest they starve or worse.”

Matilda was being honest, but she was also presenting herself as a female about whom no sane male would develop wayward notions. She’d been dewy-eyed and sweet once upon a time.

Fat lot of good that had done her.

Mr. Fenwick’s gaze remained on the foot traffic beyond the windows. He’d eaten one scone, finished off his chocolate, and was apparently waiting for Matilda to finish hers.

She’d love to fault his manners, except she couldn’t. “Say something, Mr. Fenwick.”

“We have something in common,” he said. “The status of wife is much desired in certain circles. Among young ladies, to marry well is considered the accomplishment of a lifetime, though marrying well and marrying happily are not synonymous. You attained the status of wife, though apparently at the cost of your regard for the institution of marriage. So too, with my situation. I have means and influence many long for, and I don’t want them. There he is again.”

Matilda wanted to ask Mr. Fenwick what the devil he meant by those Delphic observations, but she instead focused on the passersby. A bareheaded man in a brown suit strolled past, though he studied the surroundings as if inspecting the marvels of Pompeii rather than a typical London street.

“You’re sure that’s the fellow who was following me?”

“I’m sure. You stopped, he stopped. You moved on, he moved on. He’s passed by here twice while we’ve been eating, as if he can’t figure out where you got off to.”

The luscious scone, the rich chocolate, the pleasure of airing opinions all turned to so much bile in Matilda’s belly.

“That’s not Mr. Aberfeldy. I’ve never seen that man before in my life.”

![]()

Mrs. Bryce of the misanthropic theological theories had become a subdued creature who followed Ashton out the back of the coffee shop and accompanied him through gloomy alleys and side streets into a tiny back garden.

“We have a problem,” she said, surveying her own back door. “This door locks from the inside rather than with a key. Pippa has likely sought her bed, and my key fits only the front door.”

Ashton could go around to the front and let himself in, but whoever was following Mrs. Bryce had seen her accept his escort. The sun had set, a single cricket was trying to ignore the spring chill, and Ashton was not about to leave a woman alone in the gathering darkness if he could help it.

“We’ll improvise.” He extracted his folding knife from his boot and examined the ground-floor windows. The house was old, glazing cost money, and he was determined.

“That is a nasty bit of weaponry, Mr. Fenwick.”

“Success in life is largely a matter of having the right tools.” If you were a bastard. If you were not, then coin and social connections would suffice.

The first window had been tightly latched, but the second, which opened into a sitting room, proved accommodating. Ashton used the slim blade to lift the latch from the outside and soon had the window open.

“Don’t let Helen see you do that,” Mrs. Bryce said. “She’ll get ideas.”

“She needs an entire team of instructors and tutors,” Ashton said, tossing the package into the sitting room and hoisting himself through the window. “For that child, a single governess wouldn’t stand a chance.” He leaned out the window, scooped up the lady, and hauled her in after him. Mrs. Bryce was a curvaceous armful of female, agreeably scented with lemon verbena, and he’d caught her by surprise.

A pleasure that.

She yelped, and the instant her feet touched the carpet, she jerked away from him. “You might have simply unlocked the door for me, Mr. Fenwick.”

He picked up her package and passed it to her. “You’re welcome. Why was that man following you? Does he covet your house as well?”

If Mrs. Bryce thought the lovestruck Mr. Aberfeldy was solely interested in her real estate, she was daft.

“I’d never seen him before. I told you that.”

The parlor was all but dark. Lighting candles or starting a fire in the hearth would mean a trip to the kitchen. If Ashton left the room, though, he suspected Mrs. Bryce would disappear to her own quarters.

Possibly for the next two weeks.

“You should replace the latch on this window.” He closed the shutters, then the window itself, and secured the latch.

Shutters kept out wind and sun, true, but their first purpose was to prevent an intruder from bashing through the glass and gaining access to the house. Shutters couldn’t serve that purpose unless they were closed and latched from the inside.

“Thank you for that very obvious reminder, Mr. Fenwick. You neglected to mention that I should chide my maid for not securing the shutters before retiring. That job, however, is mine, and I was detained by no less person than yourself.”

The parlor was chilly, Mrs. Bryce’s tone was arctic.

“He frightened you.”

Mrs. Bryce’s fear reassured Ashton, because a woman living with only a young maid on the premises and limited security was easily preyed upon. Weapons might increase her danger, because they could be turned upon her.

“You frightened me,” she shot back, rubbing her arms. “He merely trailed behind me on the walkway, along with a substantial portion of the neighborhood’s working population. You’re the one who claims that man’s attentions were cause for alarm.”

She was very frightened, indeed. Ashton took off his coat and draped it around her shoulders.

“Have you another hypothesis to explain his casual patrol of the street where he last saw you?”

Mrs. Bryce clutched Ashton’s coat close when he’d expected her to toss it back at him. “Maybe he was looking for you, and he saw you escorting me from the Goose earlier in the day. It’s been years since I’ve been pursued by any save Mr. Aberfeldy and his ilk. Then you show up, and I supposedly become quarry of a different sort.”

She’d been pursued by somebody at some time. Ashton saved that admission for exploration when he had enough light to assess her demeanor.

“I’ll need a candle for my rooms,” he said. “Shall we take this discussion to the kitchen?”

Mrs. Bryce led the way through a house grown dark, her steps sure, even on the stairs leading down to the lower floor.

“Is there a cellar below the kitchen?”

“Yes,” she said as they reached a large, cozy kitchen. “For storage and coal deliveries.”

“You’ll want to make sure your coal chute is securely locked.”

In most households, the fire in the kitchen hearth never went out. It could burn down to ashes and coals, which would be carefully banked for the night. The coals in Mrs. Bryce’s kitchen cast some illumination, enough for Ashton to see that his landlady was pale and angry.

“I know you mean well, Mr. Fenwick, and it’s possible you have spared me a problem with your escort tonight, but I have owned this house for more than five years without being inconvenienced by criminals. My lodgers, by contrast, are a good deal of bother. Please stop presuming I’m stupid.”

“I’m trying to be helpful.”

“And failing. I am very mindful of my safety, and Pippa’s. The coal chute is locked.”

He retreated into silence while she scooped fresh coal onto the hearth and worked a bellows that mostly sent ashes up the flue.

This woman did not give up, nor did she let up. Ashton admired her tenacity as much as he disliked her bitterness.

“I’m sorry,” she said, putting the bellows aside and dropping onto the raised hearth. “I ought by rights to dwell in a one-room cottage in the West Riding, where my shrewish temperament need be endured by only my cat. The income from renting out the rooms upstairs exceeds what I could make in the cent per cents. Then too, this house is worth more now than when I bought it, and I expect that trend to continue as long as I’m here to maintain the premises.”

She spouted economics, an improvement over her scolding. Ashton decided to meet her halfway, though he was tempted to snatch a candle and leave her to her ire.

“I’m more comfortable in the country myself.”

“What brings you to London?” she asked as the fire caught. “Besides the usual platitudes.”

“Duty. I became responsible for properties and the people on them a few years ago. I am obligated to perform certain functions here in London as a result. I don’t anticipate being in Town past the end of June.”

“You cannot perform these functions through third parties?”

“I tried that. No luck.” Alyssa had set him up with all manner of blushing young maidens, each more tongue-tied and well dowered than the last.

“You can sit, Mr. Fenwick. I’m not some duchess that all must stand on their manners before me.”

Even her graciousness had a bite. Ashton took the other side of the hearth, so the fire crackled between them. Shadows danced on the kitchen walls, and an old house settled in for another night.

“I’m tired,” Mrs. Bryce said. “I thought being a widow would be the great prize for which I endured years of marriage. I know that makes me sound like a monster. My husband was unkind, and those who arranged the match knew it. Now I live the smallest possible life, bothering the fewest number of people. Why would anybody want to follow me?” she asked more softly. “I’ve devoted the last five years of my life to being nobody.”

Ashton understood her lament, for he’d enjoyed very much being the next thing to a nobody.

“I might have overreacted to what I saw,” Ashton conceded. “If you’re fatigued, I should leave you in peace.”

He knew Mrs. Bryce hadn’t referred to a simple lack of sleep, though. She was weary of contending with a world that refused to accommodate her terms. Most people gave up that struggle for the lesser effort of merely coping.

She rose and took a twisted taper from a jar on the mantel and used it to light a carrying candle. The light revealed both her beauty and a bewilderment Ashton suspected she’d die rather than knowingly let him see.

“Good night,” he said, taking the candle from her. “Thank you for sharing your accommodations with me.”