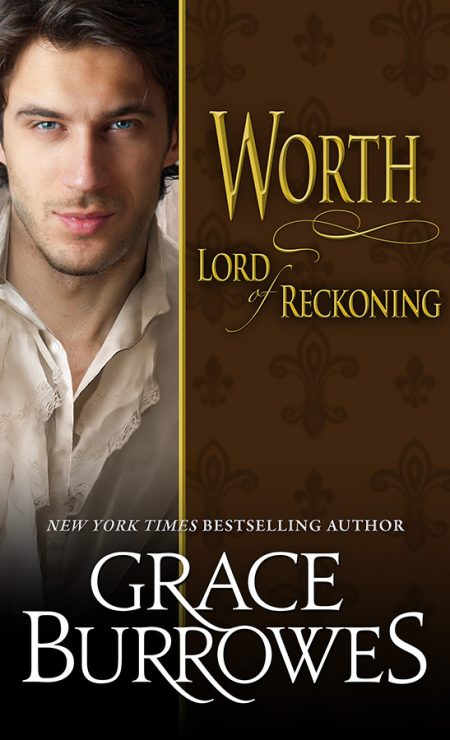

Worth

Lord of Reckoning

Book 11 in the Lonely Lords series

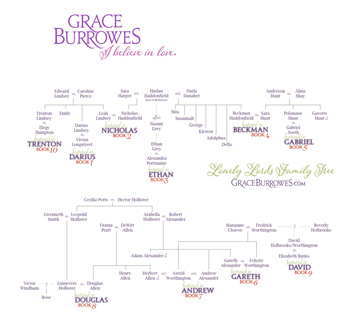

Consummate man of business and rake at large, Worth Kettering, repairs to his country estate to sort out his familial situation, trusting the ever efficient (though as yet unmet) housekeeper, Jacaranda Wyeth, will provide his family a pleasant summer retreat. To his surprise, his household is manage by a quick-witted, violet-eyed Amazon who’s his match in many regards.

As Jacaranda and Worth become enamored, the family she’s kept hidden from him, the financial clients Worth feels singularly protective of, and the ragged state of affairs between Worth and his estranged older brother Hessian all conspire to keep Worth and Jacaranda apart. Worth must choose between love and profit, and Jacaranda must decide between loyalty to her family, and the love of a man who values her above all others.

Bonus Materials →

Enjoy An Excerpt

Chapter One

“A man of business expects his home to be a haven of peace and well-ordered repose,” Worth Kettering informed his diplomatically silent butler. “And nothing aggravates this man of business like domestic upheaval, Lewis. Nothing. Not ranting clients, not crooked investment schemes, not fractious horses.”

Kettering took the proffered ribbon from Lewis.

“My housemaids are feuding, because the tweenie made sheep’s eyes at a footman fancied by the second upstairs chambermaid,” Kettering went on, lashing the ribbon around a stack of documents. “Cook has a megrim because the butcher’s boy has taken a fancy to the milkmaid. My valet is asking for yet more time off to visit his aged granny. I begin to suspect grandmamma has a penchant for the ponies, because her health only becomes tenuous during the race meets.”

Lewis supplied his finger, unasked, to hold the ribbon in place while Kettering fashioned a bow.

“And because the housemaids are running riot, my breakfast is late—and I’ve early appointments awaiting me at the office.”

“And your worship hates to be late,” Lewis muttered dolefully.

“I am not a worship, yours or otherwise.” Kettering turned his scowl on the venerable footman holding a freshly brushed top hat and pristine gloves. “Don’t dare encourage him, Means. Lewis’s immortal soul is imperiled enough without your corrupting example.”

“Duly noted, Mr. Kettering, sir.”

Lewis passed Kettering the morning post, which provoked yet more scowling.

“And now I see, as if my day had not begun on the most sour and insubordinate of notes, that my housekeeper is writing to me again. This cannot be good news, gentlemen. Wyeth always writes on the first, and that report was received a week ago.”

“Bad news it is, then,” Lewis said. “A tragedy, at least.”

Means surrendered the hat. “Perhaps a catastrophe or even a disaster, if I may be so bold. We can put the priest on alert, Mr. Kettering.”

“Laugh all you want, but you two sort out the warring parties under this roof. Our dear Mrs. Wyeth would never tolerate the mayhem that passes for management of my Town household.” Kettering stuffed his correspondence into a saddlebag. “And settle the maids down before I return tonight.”

Lewis bowed low. “Of course, your highness.”

Means followed suit. “Consider it done, Mr. Kettering, sir.”

“You’re both fired,” Kettering said, slapping his top hat on at an angle between jaunty and rakish. “That’s twice this week, and it’s only Wednesday.”

Lewis popped back up. “I’ll do better next week, your archangelness. Once a day is my goal.”

“Bother you both.”

Kettering banged out the door, grateful at least for a competent steward and tolerant butler. Lewis wasn’t more than twenty, but he had common sense to go with his excellent recall of documents and details. He’d do, if some female didn’t come along and distract him from a perfectly satisfying career in business.

Kettering swung up on his waiting gelding and considered again purchasing a coach well-sprung enough that a man might read and write as he traveled from place to place. By Kettering’s estimate, he wasted several hours a week trotting from office to house or house to office, time that could have been spent reviewing accounts or correspondence, checking figures—time spent checking figures appealed particularly—or considering investments.

Instead, he consigned himself to getting a little exercise—his commercial and domestic establishments were less than a mile apart—and doing so in the company of his horse, a generally obedient soul named Goliath.

Kettering passed his gelding into the keeping of a groom at the mews behind his office and handed the saddlebags to a junior clerk. The boy took off with his burden, and Kettering had the satisfaction of knowing his documents would be on his desk before his horse was unsaddled.

“Morning, Mr. Kettering,” Jones, his senior office clerk, chirped. Jones was off his high stool, a clutch of files in his hand as Kettering passed from the anterooms into the back of the house that served as his office. Because late nights were common enough, the bedroom upstairs was fitted out with the standard amenities. The ground floor held elegant parlors where the clients could sip tea and nibble crumpets, but most of the house was devoted to Kettering’s dearest mistress of long standing—business.

“Your first appointment, Tremaine St. Michael, sent word he’d have to reschedule,” Jones began, as they moved through the house. “He said he’ll wait until the Season’s over to try again, because mornings don’t suit.”

“When one is out swilling champagne until all hours, mornings don’t exist,” Kettering replied. “Who came after St. Michael? Darius Lindsey, I think.”

“Yes, sir. He’s usually punctual.”

“Younger sons generally are.” Kettering passed his gloves to Jones when that good fellow had stacked the files on the desk. “I’ll need some breakfast, Jones, my house being at the mercy of feuding domestics this morning. Please do not disturb me thereafter until Lindsey arrives. I didn’t get to read my personal correspondence while dining at home, and I will be in a pet until I’ve caught up. Strong China black wouldn’t go amiss. Thank you, Jones. Now, shoo.”

“I’m gone.” Jones bowed with a smile and disappeared.

Clerks were supposed to be quiet, quick, and adept at providing what was needed before it was needed. Jones had all three qualities and would soon have his journeyman’s letters as well. God be praised, he hadn’t yet been snabbled by some ambitious shopgirl looking for a settled and comfortable life, but it was only a matter of time. Shopgirls cost Kettering more articled clerks than every illness and evil known to the realm.

A tea tray with scones, jam, strawberries and butter appeared at Kettering’s elbow, brought in by a junior clerk, and silently placed on the desk.

Kettering peered at the tea and decided it could steep a bit while he read a letter or two. He pulled the one from his housekeeper off the top of the day’s stack and tried to push aside his sense of foreboding. Dear old Mrs. Wyeth had been hired sight unseen through the agencies a few years ago, and she’d been the soul of efficiency ever since. Once a month, she sent him her little reports. Once a month, Kettering told himself it was time he learned to rusticate again.

Wyeth was a sensible old thing. If she was writing on some date other than the first of the month, she’d have good reason. He slit the letter open, started reading, and promptly forgot about scones, butter, tea, appointments, and clients.

![]()

Jacaranda Wyeth had an abiding affection for her employer. She’d never even met the man, and yet, she would miss him when she turned in her notice at summer’s end.

Dear old Mr. Kettering toiled away month after month in London, and she often pictured him in his stuffy, damp quarters in the City, poring over arcane legal minutia. He’d likely become elderly before his time due to that damp—most solicitors were elderly, because it took so long to become one—and he’d squint, from having had to copy documents by the hour in bad light when he was just a boy. The poor dear no doubt suffered rheumatism in his knees, too, because the Inns at Court were notoriously difficult to heat and courts would sit even in the coldest months.

So she didn’t begrudge him his monthly report, but rather, delighted in tallying the house expenditures to the penny. Once, early in her tenure in his employ, she’d tallied her sums so they were purposely off by tuppence, and he’d discovered her error.

She’d particularly liked him for that, for his scrutiny meant he cared something for the home he never saw in Surrey. He paid attention, as Jacaranda herself paid attention, and she respected the trait on the rare occasion she found it in others.

And because she cared in some fashion for the man, she’d sent last week’s letter. Ladies and gentlemen didn’t correspond, but she wasn’t a lady. She was in service, and that meant reporting to her employer.

And when the school had contacted her, asking for his whereabouts, she’d had no reason not to tell them. The Offices of Worth Kettering were of some repute—she read the London papers and saw mention of same, always with respect. But, for some reason, the school hadn’t known he was that Worth Kettering, and she’d obliged by informing them of his direction in Town.

No doubt, they wanted a charitable donation. Any man who kept such a beautiful home without even visiting it had some means. Mrs. Wyeth also corresponded with Lewis, her counterpart in the Kettering town house, and knew Mr. Kettering was rearing a little niece. Perhaps the child was approaching school age, and the institution sought to solicit Kettering’s favor.

![]()

“I do not have a sister.” Kettering kept his voice civil only by effort, for memories of Moira were still painful. “The topic is sensitive, you see, because I had a sister. You will note the past tense.”

Mrs. Peese heaved herself to her feet. “And our condolences on your loss, but Yolanda was quite, quite clear that you are her brother. When I checked the files, the earl named you as his alternate in the event of an emergency. This constitutes an emergency.”

Was there any being on earth as difficult to enlighten as a veteran schoolmistress? “I do not have a sister living on this earth. How many times must I say it?”

Mrs. Peese reminded him of his mental picture of his housekeeper: iron-haired, well fed, full of energetic competence, and inflexible about dust, dirt, and the divine right of kings. He’d get nowhere with this woman using reason and probably less than nowhere using threats of force.

He bowed to the inevitable. “Why don’t I simply hire the young lady a coach and have her delivered to the head of our little family?” The preferred option, as far as Kettering was concerned.

“He’s left for Scotland, Mr. Kettering, as I’m sure you’re aware.”

“For God’s sake, I am not aware of the earl’s holiday schedule!”

She folded her arms across an ample bosom. By her lights, Kettering had likely committed three mortal sings in one sentence: He’d raised his voice, taken the Lord’s name in vain, and disrespected a peer of the realm. God—Gads, rather.

You are a gentleman, he reminded himself. You are always a gentleman when dealing with ladies, clients, and children. Most ladies, in any case.

“Brother?” A coltish blonde stood in the doorway to Mrs. Peese’s office. “Do you denounce me out of ignorance or out of spite?”

“Who the dev—deuce?”

“Yolanda.” Mrs. Peese’s expression became long-suffering. “Child, please return to your room. Your brother and I will negotiate the terms of your departure.”

“Not if he has anything to say to it.”

The young lady advanced into the room, and Kettering knew a moment’s unease. On some level no man of business ever ignored, she upset him. She was in the last throes of adolescence and tallish—all the Ketterings were tall—and she had blond hair and blue eyes highly reminiscent of Moira’s coloring. This Yolanda person held out her hand, thrusting a signet ring with a unicorn crest under his nose.

Kettering knew better than to stare at that ring, or touch the matching one on his own left hand.

“Mrs. Peese, if you would excuse my… sister and me briefly?”

“The door is to remain open,” Mrs. Peese said. “And, Yolanda, Miss Snyder is across the hall in the guest parlor if you need her. I will be only a few minutes.”

Mrs. Peese inhaled through her nose at Kettering, a warning of some sort. He was male and, in her world, no doubt suspect on that ground alone, and then Kettering was alone with a very young female who bore an odd resemblance to… him.

“What is your scheme, young lady?”

In response, she began to recite the Kettering succession right from the first baron, a wily young fellow who’d turned Good Queen Bess’s head, or so the story went. And the girl had it right, generation by generation.

“So you studied the Kettering line, because our looks resemble yours.” Kettering took a seat and gestured for her to do the same. “That hardly makes you my sister. I’m what? Twenty years your senior?”

“Not quite sixteen. A portrait of your mother hangs over the mantel at Grampion Hall. Our father had it painted when our brother was a toddler, but it still hangs there, unless Hess has moved it.”

“Hessian, who has conveniently decamped for points north.”

She sat forward in her chair and held his gaze with an intensity ladies her age ought not to be capable of.

“In the painting, your mother wears a blue turban, like the girl in the Vermeer, and she has only one earring. The earring hangs on her right ear, but the left one as you face the portrait.”

“Anyone could describe that painting to you.” He’d forgotten about it, though her recitation brought the image to mind. “You’ll have to do better than that.”

Over years and years of dealing with the law and those who broke it, Kettering had a good instinct for who was telling a desperate lie and who was telling a desperate truth. For all his posturing, his instincts put this girl in the latter group.

“Hess has gone north,” Yolanda said. “He’s hunt mad and must be off shooting grouse until cubbing starts in September. No one matters to him more than his hunters and his hounds, and the library will smell of dog all winter.”

Kettering rose and began to pace, because this would have been true of the old earl as well—and Kettering had also forgotten about the odor of hounds in the colder months. “So you’re my sister and we’ve never met, and now the school has sent for me. What do you want?”

“Do you believe we’re related?”

“Not for a moment,” Kettering said, not that he would admit, in any case. “But you’ve neatly boxed me into the classic corner of having to prove something in the negative. Why summon me now, when I had no clue as to your existence?”

“Because you must get me out of here.”

“Must, Miss Yolanda?”

She fisted her hands and shot a look at the door, then turned pleading eyes on him. “Please… I have nowhere to go. Hess is off to his grouse moor, and Mrs. Peese does not run a charitable institution. My continued presence here would be untenably awkward for everybody.”

She dropped her head forward, and that was when Kettering saw what the unseasonably long sleeves of her dress had kept hidden: bandages around her left wrist. Thick, fresh bandages.

“Perhaps you’d walk with me in the back gardens?” He put the question neutrally, acutely aware that some functionary or other was listening to every word from across the hall. “The day is pleasantly warm, and I have more questions for you.”

She must have sensed he wasn’t taunting anymore. Without touching him, without taking his proffered arm or meeting his eyes, she led him through the French doors to the walkway outside the headmistress’s office.

He gestured away from the building and put her hand on his sleeve. “This way. Now, who are you really?”

“I’m your sister, Yolanda Kettering.”

“Half sister?”

“Yes. But his lordship became my guardian. I was in Papa’s will, and Hess has never questioned my paternity.”

“Now you’re Hess’s responsibility?”

“I am not legitimate,” she said through gritted teeth. “But I am acknowledged, and I am your half-sister. Assuming guardianship of me was the best way for Papa to secure my future.”

“So here you are, at one of the most exclusive boarding schools in the Midlands, and you developed a sudden urge to see your long-lost brother?”

She tugged the cuff of her sleeve down. “I don’t know you, sir, but my options were limited. They’re watching me all the time.”

“They?”

“The teachers, the other girls, and if I try to escape again, they’ll peach on me, and then they’ll tell Hess, and I know what happens to people like me.”

“Dear girl, people who tell whopping lies are usually thrashed soundly and given a few days of bread, water, and Bible verses.”

“I’m not lying.”

“Prove it.” Kettering could feel himself getting sucked in, just as his late sister—his late full sister—had sucked him in, until it was too late, until he he’d been too far gone and his heart had held sway over his common sense.

“Your full name is Worth Reverence Kettering,” she said. “Your first pony was Arthur, a piebald Shetland you were given at age six. Your second was Bucephalus, whom you were given at age nine because Archie colicked, and your papa made you watch as he was put down. You told him you didn’t want another horse ever but got sick of walking everywhere by the end of that summer.”

“My third?”

“Ambergris,” she said, her head down as she walked beside him. “You rode him until you walked away from Kettering Hall at the age of seventeen, vowing never to return.”

“I didn’t vow to anybody who’d recall such folly.” He hadn’t even made that vow out loud. “You found my journals.”

She flashed him a smile, one that exposed a terrible, winsome beauty in the near offing. “You were a dramatic young fellow.”

“You’re still not my sister, but you’re in trouble here. Be honest with me now, and I might try to help you. Why do you need out of here so badly?”

“They’re kicking me out,” she said. “Some duke is thinking of putting his daughters here, and my unfortunate origins mean I’m de trop. If you can’t take me off Mrs. Peese’s hands, she might arrange for me to go to some sort of private sanitarium—the girls have been whispering about it all week.”

Whispering where they knew she could overhear, no doubt. The compassion of rich little girls hunting in a pack was a terrifying prospect, though Kettering didn’t believe for a moment the duke’s daughter was the sole explanation for the present situation.

“If a place like that gets hold of me,” Yolanda went on, “I’ll lose my reason in truth. In the alternative, if you walk out of here today, she might put me in a coach with Miss Snyder and deliver me to your doorstep tomorrow. She isn’t about to send Miss Snyder all the way to the West Riding merely to see me safely home.”

“Are your reasoning powers intact?”

“Not quite, but I’ll bear up long enough to impress your fraternal obligation upon you.”

She lifted her left hand to touch a single white rosebud, saw his eyes light on the bandages, and tucked her hand out of sight immediately.

“Pack your worldly goods,” Kettering said, “and be ready to leave this afternoon when my town coach arrives.”

![]()

“Mrs. Wyeth?” Simmons, the butler, tapped once on the open door of her private sitting room. He tottered in, wheezing and waving a piece of paper, his old-fashioned wig already askew and it not even nine of the clock. “The most extraordinary thing has happened. Most extraordinary!”

Jacaranda gestured to her little sofa. “Please have a seat, Mr. Simmons. You must not excite your heart.”

“Sound as the day I was born.” He thumped his bony chest with his fist, then more or less fell bottom first onto the sofa. This was his typical method of taking a seat, the referenced natal day being a good eighty years past. “Best ring for your hartshorn, dear lady. This might overset even you.”

A cat peeing in the servants’ hall was enough to overset Simmons, and Jacaranda had never owned a personal stock of hartshorn, not even the spring she’d made her come out.

“Have some tea, sir, and calm yourself.”

“We’re to be visited, Mrs. Wyeth.” He flourished the letter again. “Visited!”

She passed him his tea. “By whom?”

The vicar occasionally rattled out this way when he was in need of fresh air and a good game of chess. A weary traveler might stop at the kitchen door for a meal or a drink. They had visitors from time to time, of a sort.

“Himself!” Mr. Simmons waved the letter again. “Mr. K! In person! He’s coming to visit, and we’re to make ready the family rooms.”

News, indeed. Good news, in fact, for Jacaranda wanted at least one occasion of tending to her employer before she left Trysting. “We’re to ready all of the family rooms?”

“Here.” He passed her the letter, and she took it, but paused to hook a pair of reading spectacles to her ears.

“He says the family quarters.” She pursed her lips, for that was about all the missive said. Knowing the state of Simmons’s sight and the more significant of Simmons’s agendas, she read aloud.

“‘Ready the private family rooms, for I will be in residence starting the first of the week. Alert the staff and lay in appropriate stores for an extended stay.’”

“Well, my girl.” Simmons set down his teacup, having drained it in one swallow. “You’d best get busy.” He reached for one of the three tea cakes she’d set out on her own plate, revealing a second and no less familiar reason for disturbing her morning break.

“Busy, Mr. Simmons?”

“Preparing the rooms, dusting the bedrooms, cleaning the windows, turning the sheets, polishing the silver, whatever it is you do.”

“That’s all done regularly, Mr. Simmons. You know the routine here.”

He looked disgruntled, as if somebody had stolen his mug of grog.

“The andirons might need blacking,” she offered. “Though that falls to the footmen, and they are your province. I’ve no doubt you already have your fellows dusting the library and the estate office, cleaning the windows and sanding and beating those rugs?”

His bushy white brows beetled. “Of course, of course. Don’t suppose you could make me a list? In the excitement, a detail or two might slip from their lazy minds.”

She jotted him a list—in a large, printed hand—and made him finish another cup of tea before he tottered off with his list in hand.

She would miss even Simmons when she left Trysting. Simmons was a dear, and no doubt a contemporary of Kettering’s. Why else would such an otherwise modern estate sport an eighty-year-old butler?

![]()

The difficulty with having a household of elderly retainers was that one had to do many jobs without appearing to overstep the post for which one was hired. Noses got out of joint, if for example, Jacaranda pointed out to Cook that raspberries had a very short season and if not picked when ripe, the entire year’s opportunity for jam and pies was gone.

So one had to suggest the maids might enjoy a day outside and intimate that oneself might enjoy the outing as well, and then covertly keep a half-dozen giggling, romance-obsessed girls at the task of picking berries for hours on end.

Come winter, the raspberry jam would be worth the effort. At present, though, harvesting raspberries was a hot, buggy, thankless job, one that would tempt a devout Methodist out of her stays. And Jacaranda was neither devout nor Methodist, though on Sundays, she was known to be sociable in the churchyard.

“I think that’s the lot of it,” the oldest of the housemaids said. “We’re for a swim now, Mrs. Wyeth. You promised.”

“I did promise, but keep quiet. You know the fellows will try to peek.”

“So tell old Simmons to give the good-looking ones a half day.”

Millie flounced off, grinning, and Jacaranda let her go without a scold. The day was broiling, and the girls had picked a prodigious amount of fruit in a few hours. They’d done so, of course, because they’d been given an incentive for making haste.

With the maids off to splash about in the farm pond, Jacaranda hitched the pony grazing in the shade into the traces of the cart. She’d have to walk the little beast more than a mile to the manor house, a pony trot being a sure means of bruising fruit. Having been picked, the raspberries would be put up that afternoon, for even half a day in the pantry would see them mold.

So Jacaranda spent the afternoon pretending she enjoyed helping with the preserves, pretending her mother had always made a day of such things, when in truth her mother had ventured no closer to making jam than when she’d applied preserves to her perfectly toasted bread each morning.

“Mama knew a thing or two,” Jacaranda decided when the jam was made and she could finally take off her apron. Evening had fallen, the long, soft hours of gloaming when the sun had set but the earth held on to the light.

“Your back troubling ye?” Cook asked. She’d been in Surrey for decades, but the broad vowels of the north abided in her speech.

“A twinge,” Jacaranda allowed. “Putting up the fruit makes for long days.”

“Raspberries is the worst for spoiling,” Cook replied. “Good to have it done. Apples and pears is more forgiving. Even the cherries ain’t so finicky.”

“Fragile,” Jacaranda agreed. “But we’ll have preserves to put in everybody’s basket at Yule.”

“And shortbread.” The gleam in Cook’s eyes was particularly satisfied, because she’d conspired with Jacaranda to have their dairyman stagger the breeding of the heifers so they didn’t all freshen at once. Staggering the herd meant Mr. Morse didn’t get three months off with no milking, but it also meant the estate always had some fresh milk and butter without having to buy from the neighbors.

“Did I smell some shortbread baking this very morning?”

Cook’s wide face split into a smile. “That you did, in anticipation of the blessed event.”

“He isn’t supposed to arrive for another day or two,” Jacaranda said. “And the place hardly needed much attention to be ready to receive him.”

“Maybe not on your end.” Cook retrieved a plate of shortbread from the pantry. “I haven’t cooked for the Quality for going on five years. The larder needed attention, and I’ve yet to work out my menus past the first meal.”

Jacaranda accepted a piece of shortbread, only one, though Cook had cut pieces sized to appeal to hungry footmen, bless her. “I don’t suppose you’d show me what stores are on hand?”

“Put the kettle on, Mrs. Wyeth.” Cook popped a bite of shortbread into her mouth. “This might take a cup or two of tea.”

By the time Jacaranda had a week’s worth of summer menus planned with Cook, full darkness had fallen and bed beckoned. The moon was up, though, and rather than make the tired staff lug a tub and water up to her room, Jacaranda threw towels and soap into a wicker hamper, along with a dressing gown and summer-length chemise.

The pond nearest the house wasn’t merely ornamental. With a pump and an elaborate set of pipes, it served the stables, the laundry, and several other outbuildings. The pond was, however, relatively private, being ringed by tall hardwoods and fringed with rhododendrons on three sides.

On the fourth side was a grassy embankment, and there Jacaranda settled with her hamper. She’d done this before, usually on nights when she couldn’t sleep.

On nights without a moon.

On nights when dreams were something to avoid.

Tonight, tired as she was, sleep wasn’t yet close at hand. She wasn’t excited, but others at the house were excited over Mr. Kettering’s arrival. The excitement was like that of an unruly child—impossible to ignore. She’d swim off the aggravating vestiges of vicarious nerves, get clean, and enjoy a little privacy.

Her dress came off, then her shift, then sabots, leaving her standing naked in the moonlight and comfortable for the first time in a long, hot day. She dove in from the rock God had positioned for that purpose and made a long, slow circuit of the pond. It was more of a small lake and boasted enough depth at the center that the occasional lazy groom could be seen fishing from a small boat.

Lazy was not in Jacaranda Wyeth’s ken. When she’d done her laps, she put the soap to its intended use and prepared to leave the water.

Hoofbeats interrupted her consideration of the next day’s list of things to do.

Hoofbeats, coming up the driveway, at this time of night.

She was in the shallows before she realized the rider would come right past her end of the pond on his way to the stables. Probably a truant groom who’d stayed too long at the posting inn in Guildford.

She toweled off hastily and shrugged into her shift and wrapper, hoping the man’s guilty conscience and the befuddling effects of spirits might conspire to keep her from his notice.

And they might have, except the beast was apparently a town horse. To Jacaranda’s eye, the handsome gelding looked like that type whom squawking chickens, crossing sweepers, runaway drays, and rioting mobs wouldn’t deter from his appointed rounds, but a pale blanket spread on grass by moonlight had him dancing sideways.

“Everlasting Powers, horse, it won’t eat you.”

A splash, as some frog took cover underwater, might have suggested to the horse his master was flat-out lying. Either that, or the beast sensed the proximity of hay, water, and fellow horses.

“Damn and blast, Goliath, would you settle?”

Goliath settled, albeit restively.

“Around to the stables with you, beast, and at the walk if you know what’s good for you.” The beast must have known exactly that tone of voice and walked daintily on down the driveway.

Jacaranda blew out a breath of relief and folded her towel into the hamper. She knew of no riding horse in the stables named Goliath, and as large as the animal was, she would have recognized him.

Across the water, a groom banged down the stairs from the quarters over the carriage house, and a lantern sparked to life in the stable yard. Working quickly, Jacaranda began to plait her wet hair. Whoever had wakened the stables would likely quarter with the grooms at this hour, but she wasn’t about to be caught in dishabille. A gaggle of maids could safely appropriate the pond when the menfolk were occupied elsewhere, but the housekeeper swimming alone after dark would not do.

“You there,” a masculine baritone said from the shadows of the rhododendrons. “Explain what you’re doing on my land, and explain now.”

The tone of voice, imperious, vaguely threatening, definitely intimidating, arrived at Jacaranda’s brain before the content of the words did. What registered was that she was alone, barely dressed, after dark, outside, with a strange man. The shadow detached itself from the surrounding darkness and proved to be of considerable size. She opened her mouth to scream, but nothing came out.

Her legs were not as unreliable. She would have pelted barefoot for the house, except the day before had been rainy, the bank was grassy, and the maids had slicked the grass down to mud with their frolicking.

At the last instant before she toppled into the water, Jacaranda’s foot slipped. Instead of a graceful arc over the water, she tumbled and fell, pain exploding in her head as she hit the water with a great, ungainly splash.

Chapter Two

“Breathe.” Kettering pushed dark, wet ropes of hair off the woman’s forehead and spoke more sharply. “Madam, I told you to breathe.”

She didn’t breathe, but she coughed and rolled to her side, bringing up water and yet more water. Then she shivered even as she tried to roll away from him.

“None of that, or you’ll be back in the pond, and I am not rescuing you a second time.” He eased his hold, his mind insisting she was well, despite the galloping of his heart.

“Rescuing me?” She scrambled to untangle herself from him, getting as far as a sitting position, her mouth working like an indignant fish’s. “Rescuing me, when you all but caused me to slip when I tried to depart your unwelcome company? I’ve never heard the like.”

Her pique was almost humorous, given that her nightgown was sopping wet and her curves and hollows tantalizingly obvious in the moonlight.

And yet, she had dignity, too. Damp, disheveled dignity, but dignity nonetheless.

“Madam, you panicked,” Kettering said, taking off his riding jacket. His coat was dusty, but he settled it over her shoulders in aid of her modesty, which was no doubt soon to start troubling her. “If I hadn’t hauled you out of the water, you’d be feeding the fishes as we speak.”

“I am an excellent swimmer,” she retorted, drawing herself up, though her throne was a grassy moonlit bank.

“I beg to differ.” He lifted his hand slowly and settled it on the side of her head. “You’re raising a bump the size of Northumbria. Nobody’s an excellent swimmer when they take a rap on the noggin like this.”

She touched her hand to the side of her head, and he took her fingers and gently guided them to the site of her injury.

“Lord abide.”

He rose, and she gaped up at him. He wasn’t that tall. He knew of at least one man who was taller, several who were as tall, and still the gaping abraded his nerves. He extended a hand down and drew her to her feet.

And gaped.

“I must look a fright,” she said, but to him…

She was tall for a woman, wonderfully, endlessly, curvaceously tall. When dragging her from the water, only vague impressions had registered—some size, some female parts, not enough breathing. His coat had slipped from her shoulders as she rose, and he might as well have seen the woman in her considerable naked glory.

He picked up his coat and draped it over her shoulders again. “I’ll carry your effects, you keep the jacket, and we’ll find some ice for your bruise.”

“The ice stores are always low this time of year.”

“Then we’ll put the last of it to good use,” he said, gathering up her hamper. “Worth Kettering, by the way, at your service.”

She remained quiet as they moved along the garden paths toward the back of the house, and he wondered why she wouldn’t give him even one of her names.

She came up almost to his chin, a nice, kissable height, and she moved with a certain confident grace, though he kept their pace slow in deference to her injury. Best of all, she didn’t chatter. He could only hope she lived on one of the neighboring estates and enjoyed the status of merry widow.

Worth had a particular fondness for merry widows, and they for him, over the short term in any case. He was good for an interlude, a spontaneous passion of short duration—short being sometimes less than a half hour but invariably less than a week.

He’d studied on the matter and concluded women wanted more than a little rogering—that was the trouble. They wanted gestures, feelings, sentimental notes, bouquets, and passion, and he was utterly incapable of all but the passion.

He was so lost in a mental description of the follies resulting from females embroidering on passion—the notes and waltzes and flowers and whatnot—that he nearly didn’t notice when the lady at his side preceded him into the back hallway leading to the kitchens.

Sconces were still lit along the corridor, though, so he let her lead the way and used the time to marshal his sense and admire the confidence in her stride.

“You will please sit,” he instructed his companion.

Her lips thinned, but she plopped her wet self down at the long kitchen worktable, one that had been scarred and stained when Kettering had been a lad. He was pleased to note his initials had not been smoothed off the far corner in the years since his childhood.

“I suppose tea would be in order,” he decided, hands on hips. Thank a merciful God, there were coals on the hearth and a pot of water ready to swing over the heat. He quickly assembled the required accoutrements, aware of his guest watching him the whole while.

“Perhaps you’d better speak,” he suggested, “lest I get the impression a blow to the head has stolen your faculties. I’ll put some sustenance on a plate, if you don’t mind. The ride out from Town is damned long—pardon my language—and I didn’t intend to finish my journey with an impromptu rescue at sea.”

“You certainly make yourself at home in the kitchen,” the lady remarked, and her tone said clearly, she did not approve of his display of domesticity.

“I’m a bachelor.” He demonstrated his bachelor savoir faire by not leering at her as he spoke. “One learns to manage or one starves. Even the best staff is somewhat at a loss for how to cosset a man of my robust proportions.”

Her eyes drifted over him, calmly but thoroughly. He was as wet as she, and he didn’t mind the inspecting—inspecting was all part of the dance—but he did mind being ravenous.

“You’ll pardon me while I nip out to the icehouse to see if we can’t find something cold for your head.”

“That really won’t be necessary,” she said, starting to rise, only to sit right back down, her hand going to her temple.

He scowled mightily, because fainting on her part would be a damned nuisance for him. “Keep to your seat. There’s no such thing as a minor head wound, and I can’t have a guest neglected on my property.”

“I’m not a guest.”

He cut her off with a wave of his hand as he made for the back door. “Guest, trespasser, vagrant, tinker, what have you. You need ice.”

![]()

Jacaranda sat, refusing to shiver in the deserted kitchen and wondering if she could make it as far as her quarters unaided before Captain Charmless returned. This must be some arrogant young namesake of her employer, an opportunistic nephew thinking to sponge off the old gentleman for the summer’s visit. Perhaps an heir inspecting his expectations, for he kept using possessive pronouns—my, mine, and the like. She’d set him to rights when her head stopped throbbing and the room stopped expanding and contracting every time she moved.

The fellow wasn’t entirely without use, though. He came back into the kitchen bearing a bowl of chipped ice, an incongruously cheerful red-checkered towel over his shoulder.

“Plenty enough ice left for our purposes,” he said. “I’ll have to speak to Simmons about ordering some more. Hold still.”

That was all the warning he gave Jacaranda before he held a towel full of ice firmly to the side of her head. The pain of it caused her meager shortbread dinner to rebel and had her ears roaring again. When the roaring subsided, she was aware of the discomfort traveling even into her shoulder and of the way the ice against her wound made her head both freeze and burn at the same time.

“Woman, you will hold still. You’re in no condition to be delivering set-downs or lectures or whatever it is you’re planning to deliver. Soon, your head won’t hurt so badly, I promise.”

His voice was brusque, as he held the towel against her throbbing skull with one hand. With the other, he cradled her jaw, imprisoning her cheek against a washboard-firm stomach. His shirt was damp, of course, but through the dampness the heat of him warmed her jaw. She should have shot to her feet with the indignity of it.

Should have delivered a set-down wrapped in a lecture tied up with a sermon.

She leaned closer to his warmth.

“Better, hmm?” He took the towel away. “Bleeding has stopped, too, thank the Everlasting Powers. Could you hold this here?” He took her hand in his and anchored the towel to her scalp again. “I’ll fix us a spot of tea. You’re pale as a felon awaiting sentence.”

He moved off, and that was a relief. Jacaranda held the melting ice for as long as she could, but the cold penetrated her hand as effectively as it had her head, and her teeth were threatening to chatter. She distracted herself from the chill by watching Kettering bustle around the kitchen. For a big, rather wet man, he moved silently. He was in stocking feet—he must have left his footwear in the back hall for the Boots—breeches, waistcoat and shirt, and his clothing left nothing to the imagination.

This version of Worth Kettering wasn’t some retiring, scrawny functionary holed up at the Inns of Court with a flannel around his dear wattled neck. This fellow looked like he split wood, shod horses, and loaded sea-going vessels in his spare time.

His height was the first thing Jacaranda had noticed. Added to his height was his darkness: dark hair—particularly when wet, of course—and a burnished cast to his skin that suggested he frequently went without his hat—and shirt.

But beyond his appearance, he bore an energy that would have had Jacaranda scooting out of his path, if dignity would allow such a thing. Coupled with that energy was a brisk competence, which, at the moment, she appreciated.

“Drink.” He put a cup of tea before her, as if she were a recalcitrant denizen of the nursery.

“Oh, now…” He set the tea tray down and lowered his presuming self right beside her. “Settle your hackles, duchess. What self-respecting Englishwoman refuses a nice hot cup of tea?” He wrapped her hands around the cup, his own cradling hers on either side of the mug. “See? Feels good. Now, don’t be contrary when you know you’ll enjoy your tea.”

He took his hands away, having made his point, and Jacaranda’s inchoate chill was abruptly supplanted by a peculiar heat rising from her middle.

“You’re blushing,” Kettering informed her. “I’m charmed, but you’re still not drinking your tea, and until you have a sip, I can’t touch mine.”

She drank her tea, a cautious taste at first, but he was right: It was hot, strong and sweet, and the first cup of tea she’d ever had prepared by a man. The taste was disconcertingly good.

“Better, right?” He set his empty cup on the table. “I should have a housekeeper around here, and she might have something dry you could borrow. It’s dark out, thank the Deity. No one need see you in a servant’s attire if we wrap you in a dark cloak and take you home in a closed carriage.”

“I beg your pardon?” Servant’s attire?

“I’m rather fond of the old dear,” he went on, “and one doesn’t want to give offense to loyal retainers. She’s the closest thing to a decent female on the premises, unless you want me canvassing the neighbors for some clothes?”

“I will wear my own clothes, thank you very much.” She pushed her half-finished tea away and made to rise, but he’d boxed her in on the bench, and as soon as she made it to her feet, her head sounded a trumpet fanfare of pain that blared down her neck and even into her chest and arm.

“Perishing damned females, excuse the language,” he muttered while he gently tugged her back down beside him. “I don’t supposed you’re married, and that’s what all this misguided dignity is about? You will tell me now if some anxious husband must be dealt with—I insist on honesty from the women I rescue.”

She sank onto the bench, mortified to feel another flush—it was not a blush—accompanying the pounding in her skull. How busy her bodily responses were after such an insignificant bump on the head.

“Naughty girl,” he chided, his arm around her waist. He used his free hand to sweep her wet hair back over her shoulder, the better to mortify her by studying her wound.

“Now listen to me, duchess, because I am not at all accustomed to explaining myself.” He drew his hand over her hair again, as if to move it, except the entire damp curling mass of her former braid was lying back over her shoulder. Then he did it again. And again.

“My newly discovered baby sister is coming to join me here tomorrow—a schoolgirl, but at that dangerous, almost-hatched age, you know? Then, too, my niece will be coming along, and she’s a frightfully noticing little thing. I can’t put my housekeeper’s nose out of joint when I’ve all but ignored my own property for five years.”

Still that slow, beguiling caress continued over Jacaranda’s damp hair. “It’s a man’s right to ignore his possessions, but housekeepers are women, and they take on about such things. They get attached to their routines, and I’ve every intention of ignoring the place for another five years once I get these infernal girls sorted out. So we’ll not be upsetting my dear Mrs. Wyeth, hmm?”

Jacaranda lifted her head from his shoulder, having no idea how she’d assumed such a misbegotten posture.

“You are without doubt the most conceited, managing excuse for a grown man it has ever been my misfortune to share a pond with.”

His hand disappeared. “Be that as it may, you will not upset my housekeeper with airs and ingratitude, regardless of your mood, station, or dented noggin.”

“There’s no need for me to upset her,” Jacaranda shot back. “You’ve already done a thorough job of it.”

![]()

Worth’s midnight mermaid was scrambling his tired wits.

She was pretty, likely the source of the problem. He had a weakness for pretty women, though he’d learned long ago they had no weakness for him. The pretty ones fretted at the most inopportune times about whether their hair was mussed, and he, of course, liked to muss a lady’s hair. Then, too, pretty women were always looking past one’s shoulder to see who was watching and to whose more interesting, titled, or wealthy side they might flit.

Still, they were pretty, and beauty in a female could mesmerize him, despite common sense to the contrary.

The lady in his kitchen was a tad exotic, all her features and colors one detail away from perfection. Her eyes were not the fashionable blue. They were gentian, almost lavender, and so luminous as to look as though they belonged to some temple cat in human form. Her hair was not quite black, but on the curling ends looked sable to him, and it fell down her back in a cascade of curls and twists and flyaway strands that begged a man to plunge his hands into its depths.

Her hair looked in want of taming, and he liked that. She probably hated her hair, being female. He knew better.

But as he rose and mentally appreciated her too-generous mouth and somewhat Nordic nose, his solicitor’s brain also tried to assemble facts on a different level.

“You knew how much ice was on hand,” he said, treating her to a thoughtful scowl.

She scowled back. “You aren’t a little old fellow hunched over his desk at the Inns of Court.”

Whatever that meant. “You knew your way to my kitchen, without the least guidance.”

“I assumed you’d need a map. I took pity on an absentee landlord.”

“Absentee owner,” he shot back, his brain still unhappy with the logical conclusion.

“Absentee in any case.” Her humble bench might have been a throne for all the accusation in her glare.

“What is your name?” He softened his tone, in deference to another one of God’s impending nasty jokes. She might, were there a merciful God, be an acquaintance of his housekeeper’s, one used to the friendly cup of tea after services.

Which were held five miles away, if memory served.

“My name is Jacaranda Wyeth.”

“I don’t suppose your dear mama is in my employ? And what sort of name is Jacaranda?” And why was he doomed to deal with women who were unforthcoming regarding the simplest truths?

“I am in your employ, or I was as of recently.”

“You’re not quitting.” He used his best unruly-client voice. Settled ’em down instantly, though the effect on his little niece was less immediate with each application.

She tipped her chin up a mere but ominous quarter inch.

Damn and blast, she was magnificent. And troublesome.

The worst of his many weaknesses was for troublesome women.

“Drink your tea…” This earned him another quarter inch of chin raising. “Please, Mrs. Wyeth, lest it grow cold.”

But then the thought of warming her up, warming up all that magnificent Celtic temple cat beautiful exotic woman rippled across his imagination, and he had to sit down again.

Beside her unforthcoming self.

Of course.

She drank her tea, proving even a joking God wasn’t without compassion, for Worth needed the time to think of cold eel pie, privy rats, and those unruly clients. They weren’t all the same degree of distasteful, because wrangling with clients could be enjoyable, as chess could be enjoyable.

“You are my housekeeper, then?”

“And you are my employer.” She pushed her mug away, and Worth refilled it and stirred in cream and sugar. A bachelor developed such habits, or he’d start looking about for a hostess.

“How came you to be in the pond at such an hour?”

“Today was long and hot,” she said, taking a sip of her tea. “A little dip spares the maids having to lug water and the footmen having to haul the tub.”

“Suppose it does. They’re all abed?”

“Carl will be on duty by the front door. He’s reliable, and we knew you might show up in advance of your coaches.”

“How?”

“How what?”

“How did you know?”

“I am in correspondence with Lewis, who suggested you might not travel in the coach with the young ladies. Horseback is faster and likely preferable in all but wet weather.”

He did not have a weakness for managing women, no matter how tall, pretty or troublesome. Particularly not for managing, unforthcoming women—though she’d suffered a knock in head and hadn’t quite been deceitful.

“Can you call a maid to stay up with you? You might slip into a coma if we let you sleep through the night.”

“The blow to my temple didn’t render me nigh insensate, so much as the prospect of your unwanted attentions disconcerted me.”

He was silent for a moment, trying to find a different meaning for her words and failing.

“My attentions, as you call them, were in aid of preserving your life. If you seek to put period to your existence, you have my condolences. I’m still not letting you quit, though. Not until my little family sortie among the peasants is completed.”

“You have a very crude preoccupation with matters of class,” she informed him, finishing her tea. “But even you must understand I need my rest.”

He considered her, considered she was pale and wet and cold, and probably in need of a hot bath and some cosseting, else she would not be so sour-natured in the face of his consideration and concern.

But more than physical comforts, she probably wanted privacy.

“Come.” He rose and held out a hand. “I will escort you to your chambers and see you safely to bed. You can refine your insults and ingratitudes in lieu of sleep.”

She took his hand, but only after perusing it as if to examine him for scales, claws, or evidence of barnyard relatives.

She weaved a little when she gained her feet, which necessitated Worth putting an arm around her waist. That she permitted such behavior suggested she really wasn’t doing very well.

Which served her right.

The housekeeper had her own private parlor and sleeping chamber. Those hadn’t moved in the five years since Worth’s last visit, and Mrs. Wyeth let him escort her there without further comment. He decided not to be worried about her silence.

When they got to her door, he pushed it open, seeing no candle lit.

“This won’t do,” he muttered, propping her against the wall and taking down the lamp from the sconce. He lit a branch of candles in her parlor, enough that the room was minimally illuminated.

“Shall I light you a fire?”

“You shall not.” She stood by the door, his jacket closed about her in a two-handed grip.

“Then get you into bed. You’re one breeze away from the shivers.”

“You have my thanks for your efforts.” But, of course, she didn’t move.

“For God’s sake, woman, if I were going to take advantage, I’d have done so outside, in the dark, far from those who’d hear you scream, and well before you regained the use of your viper’s tongue.” He moved to the bedroom and lit a candle beside her bed.

Other solicitors referred to Worth Kettering as “a detail man.” The compliment was grudging, usually offered by somebody who wasn’t a detail man. Sloppiness was a deadly sin in a solicitor, as far as Worth was concerned, but he also understood that discipline took a man only so far toward cataloging every minute aspect of situation.

Beyond that point, an ability to perceive details was a God-given gift.

Jacaranda Wyeth’s little quarters revealed myriad details to him.

She was orderly, even in her privacy.

She liked pretty things, embroidered pillow cases, fresh flowers, a soft, quilted bedspread, lace curtains. Frilly, female things that belied the no-nonsense composure of her countenance.

He withdrew from the bedroom and found her still by the sitting room door, her teeth chattering.

“Get your wet things off. I’ll be back with some hot water for your ablutions, and a tray.”

He left her before she could insult him again, which meant he moved quickly, replacing the lamp on the sconce and heading for the kitchen. Putting together a tray of buttered bread, cheese, and raspberry jam took no time at all, neither did filling an ewer of hot water from the well on the range.

He didn’t knock on Mrs. Wyeth’s door, because his hands were full. He balanced the tray on his hip and pushed the door open to find the sitting room empty. The door to the bedroom was closed, so he put the tray on a low table—lacy runner, bouquet of violets in a crystal vase—and tapped on the bedroom door.

“Don’t you dare come in here.”

“I’ve brought you water and sustenance. I’m off to fetch a teapot. You’re quite welcome.”

He took the time to change into a dry dressing gown and pajama pants along the way, happy to find his trunks already waiting in his room. When he came back to Mrs. Wyeth’s suite with the tea tray and set it beside the food, she still hadn’t emerged.

“Either present yourself now or expect company in your bedroom, Mrs. Wyeth. I can’t have you falling and banging your head again.” He couldn’t shout, else he’d wake the house, and it wasn’t time for that maneuver in any case, because she opened the door, her wrapper having replaced his jacket.

But, still, she was cold. Her lips were blue, her teeth chattered, and her eyes had turned to chips of periwinkle ice, for her discomfort was no doubt all his fault.

“For God’s sake, come here.” He grasped her by one fine-boned wrist and pulled her into his embrace. “You will catch an ague with all this damned pride, pardon the language.” He scooped her up against his chest and settled with her on the sofa, her “d-d-don’t you d-d-dare” hissed right in his ear. He twitched an afghan down from the back of the sofa and draped it over her as she squirmed in his lap.

“Hush, woman. You’re cold, I’m warm, and a chill can be dangerous. Tolerate my proximity for five minutes, and I’ll leave you in peace.”

He ran his hand over her back, feeling the tremors of her shivering.

“Cuddle up, and hold your tongue,” he admonished. “You know you will otherwise crawl between cold sheets and fall asleep without getting warm. That misery can be avoided if you’ll simply—”

“I hate you.”

Then she subsided against him and didn’t even lecture him when he rested his chin on her damp hair.

“Of course you do, but might you care to enlighten a fellow as to why?”

She burrowed closer and remained silent, suggesting her body didn’t hate him.

“I have it.” He gathered her into a more snug embrace as another chill shuddered through her. “If I have to ask, I don’t deserve to have it explained to me.”

“Brilliant.”

“But hardly original. One wants a little originality in a lady’s vituperations.”

She made a huffy noise against his chest, but at least she’d stopped shivering.

![]()

I must have hit my head harder than I thought.

Jacaranda gave up her verbal fencing with the wonderful heat source in whose arms she was nearly drowsing. There would be hell to pay for this folly tomorrow, and likely for the remaining weeks of her tenure in his employ, but Worth Kettering was wearing silk and flannel, he smelled like a fresh breeze through a cedar forest, and in his arms Jacaranda felt, at least for these moments, safe.

He was big, brusque, officious, and far too astute, but he was offering her—pushing on her, really—a comfort more seductive than wealth or chocolate.

How long had it been since she’d been held this way? Likely since infancy. In her childhood, her parents’ energies had been taken up with the younger children, particularly with pretty little Daisy who’d had weak lungs as a child.

And then Jacaranda had endured adolescence, along with the height, the nicknames, and the odd attentions from boys much older than she.

She shoved that thought and all the bewildered, shameful memories that went with it aside and rubbed her cheek against the silk of Mr. Kettering’s dressing gown.

He would have to wear silk.

“You’re falling asleep, Wyeth, my dear.”

Before she could struggle off his lap, he rose, easily, without grunting or straining or remarking on her size, and walked with her into her bedroom. He’d closed the window, probably in deference to the candle he’d lit by her bed, but it meant the room was free of drafts.

He set her on the edge of the bed, went around to the other side, and turned down the covers.

“Don’t suppose you’d invite me in to warm up your sheets?” He started stacking throw pillows on a chair, a man at ease in a lady’s bedroom. “No witty rejoinder, Wyeth? Shall I worry about you in truth?”

“I am speechless at your crude suggestions,” she managed. “Both my bedroom and sitting rooms doors have stout locks. Must I use them or have you acquired minimal notions of gentlemanly conduct at some point in your misspent youth?”

A housekeeper did not speak so disrespectfully to her employer, but he hadn’t been serious about joining her in bed—she hoped. He’d been offering an insult as a bracing conversational slap to one whose wits were wandering.

She could only return the favor—she was leaving his employ soon in any case.

“Many would agree with the misspent part,” he murmured, lifting back her covers. “Scoot in, my dear, or you’ll start shivering again, because your hair is still quite damp.” He frowned at that realization, the candlelight making him a displeased Bacchus. “Here.” He took off his dressing gown and laid it over her pillows. “Your pillows won’t take the wet.”

“That dressing gown is silk.” She lifted her legs to get under the covers, else he’d stand there bare-chested all night waiting for her. “I’ll ruin it.”

“It’s just cloth, and I can’t have you taking a chill. I thought we’d established that.”

To her horror, he sat down at her hip and brushed her hair back from her forehead, then turned her head gently with a thumb to her chin.

“This scrape might start bleeding again. Try to sleep on your right side.”

She obligingly shifted to her side—anything to make him go away.

“Good night, Wyeth.”

“Good night, Mr. Kettering.”

He rose and moved around the room, cracking her window a hair, blowing out the candle. She heard him moving in the other room, then felt the lovely weight of the afghan spread over her blankets. The light from the sitting room disappeared as he closed the bedroom door, and still she heard him, tidying up all the trays he’d brought in.

For nothing. She hadn’t eaten, hadn’t used the warm water, hadn’t had a final cup of tea.

But she did sleep.

While he did not.

Chapter Three

“They’ll be forever in there.” Yolanda flopped back against the squabs and knew she was setting a bad example for her niece. Young ladies did not flop, and they did not gripe.

She had a niece, whom she hadn’t known about, just as her brother Worth hadn’t known about her. Having a niece was disorienting, when little Avery seemed more like a younger sister and Worth Kettering more like an uncle. A grouchy uncle.

“Wickie won’t tarry,” Avery said, in French. “She’s devoted to me and now she’ll be devoted to you too.”

“Miss Snyder has that honor,” Yolanda said, not unwilling to practice her French on a native speaker. “At least until Michaelmas term starts. I wonder how much Mr. Kettering paid her for the trouble of babysitting me for three months.”

“Uncle has pots of money.” Avery grinned as if Uncle had chocolates in his pockets. “Spending some on Miss Snyder won’t hurt him. She looks sad to me, or angry.”

“She’s nervous,” Yolanda said, switching to English. “She’s one of those mousy little women who toils away in thankless anonymity in the classroom, and thinks dithering over which new sampler to start is a significant decision.”

“Uncle thanks Mrs. Hartwick, but I don’t know that other word you used,” Avery said, peering out the window. “They’re coming now.”

“With food, thank the gods.”

“Uncle says that, thank the gods.”

Uncle this, and Uncle that. The little magpie worshipped the ground the man strutted around on. Yolanda had heard in great, dramatic detail in at least two and a half languages why Avery had reason to appreciate him. She’d been orphaned on the streets of Paris for almost a year when her mother died, but had memorized Worth’s direction and eventually been sent to her uncle.

A tale worthy of one of Mrs. Radcliffe’s novels, right down to the way Worth doted on his supposed niece.

Had he asked darling Amery for proof she was related to him?

To them?

Yolanda tucked into a savory, hot shepherd’s pie, silently admitting that her brother may not have believed her, but he’d taken her in, bribed Miss Snyder to chaperone, and now they were off to the country.

And he’d likely bribed the coaching inns along the way too, because the food was excellent, and the relief teams in harness in mere minutes.

“It’s good to see you eating, my dear.” Miss Snyder gave Yolanda a hesitant smile from the other bench. “And soon we’ll be at your brother’s estate and you can stretch your legs with little Avery here.”

She patted Yolanda’s knee and took a careful bite of her meaty pastry. Miss Snyder slowly, thoroughly chewed her bite, patted her lips with a serviette, then took another slow, small bite.

Another hour, the coachman had said. One more hour, not ten miles and they’d be free to get out of the coach.

Had it been more than that, Yolanda doubted anything in the world could have stopped her from running screaming down the road. Miss Snyder, mousy, anonymous, and whatever else could be said about her, at least chose her path in life. She could have been a governess, a laundress, a paid companion, or likely some lusty yeoman’s wife—she was by no means ugly—while Yolanda was reduced to begging a berth from a brother nigh twice her age.

An earl’s daughter with a small fortune in trust—though not a lady by title—and she’d had nowhere to go.

She chewed mechanically, lest the lump in her throat rise up and humiliate her before the brat and the mouse.

Had she anywhere else to go, anywhere else at all…

![]()

“She had nowhere else to go, you see,” Mr. Kettering. “May I top off your tea?”

“Was your upbringing so backward you believe an employer should be waiting on his staff?” Jacaranda’s tone was meant to be prim, condescending even, but what came through was the sheer puzzlement. She’d been given to understand a title hung not too distant on Mr. Kettering’s family tree, and here he was, dragooning her into breakfast tête-à-tête and pouring her tea.

“And you’ll take sugar with that, to sweeten your disposition,” he concluded, pushing the sugar bowl toward her. “My upbringing was the best that good coin and better tutors could pound into me, but my mother died when I was quite young and her civilizing influence was a sorely felt lack. Have another raspberry crepe.” He portioned one off his own plate and onto hers. “You’re too thin, Wyeth. Eat.” He sliced off a bite of the crepes remaining on his plate and gave every appearance of enjoying it.

Well. They were very good, the crepes, the omelet, the toast, all of it. The tea pot was kept piping hot under embroidered white linen, the room redolent with the scrumptious scents of a kitchen determined to make a good breakfast showing before a long absent master.

And when had anybody, anybody ever, accused Jacaranda Wyeth of being too thin?

“Better,” he said, when Jacaranda started on her crepes. “Back to Yolanda, if it won’t disturb your digestion?”

Rather then speak with her mouth full, Jacaranda made a small circle with her fork, and for some reason this had her host—her employer—smiling at her over her tea cup.

And, oh dear, that smile was sweet. He was a dark man, dark haired, dark complected, dark-voiced, but that smile was light itself, crinkling the corners of startlingly blue eyes, putting dimples on either side of his mouth, and conveying such warmth and affection for life Jacaranda had to look away.

Lewis had written that even ladies appreciated when Mr. Kettering handled their private business, and in that smile, Jacaranda saw part of the reason why. Mr. Kettering was, damn and blast him, tall, dark and handsome, and blessed with that smile as well.

Thank heavens her term of employment at Trysting would soon be up.

“Your sister seems a typical young lady to me,” Jacaranda said. “Your family hails from the north, do they not?”

“They do, what few of us there are,” Mr. Kettering replied. “My older brother has had the keeping of the girl, but he’s managed it by shuffling her from one exclusive boarding school to another and he’s lately seen to it she had a schoolmate’s house to go to on holidays and breaks.”

“I gather she will holiday with us here for the remainder of the summer?”

“Just so.” His first name was Worth, Jacaranda recalled, apropos of absolutely nothing. She’d never met a man named Worth before, much less Worth Reverence.

“What can I do to make her summer more pleasant?” Jacaranda asked. “There are a few young ladies in the area she might enjoy meeting.”

“Then you should take her to meet them.”

“Mr. Kettering, it might have escaped your shockingly egalitarian notice that I am your housekeeper, but your neighbors know my station. You will take your sister calling, not I.”

His tea cup was set down with a little “plink!” of… not surprise, but disgruntlement, perhaps.

“I hardly know my neighbors in these surrounds, dear lady. And between trying to keep up with my correspondence from Town, and seeing to my property here, I do not intend to make time.”

Jacaranda had seven brothers, and Mr. Kettering’s tone had effect of battle trumpets summoning an experienced battle mount.

“You’ve neglected the land for years, and it’s well enough managed in your absence,” Jacaranda shot back. “Your sister needs you and no one else can see to her in this regard.”

He closed his eyes and jerked back, as if he’d been painfully goosed in the chest.

“You don’t save your heavy guns, do you Wyeth?”

“I have not the least idea what you mean, sir, except for a general notion that siblings ought to know and care for each other. Family ought to. I can and will make an effort to befriend the girl, and I can take Avery to play with the neighbor’s children, provided you visit them first and send the requisite inquiring notes.”

“I have to visit before my niece can even take her damned doll calling on other children?”

“And you have to make the girls think you’ll enjoy it,” Jacaranda added just for spite. “I suggest you start with Squire Mullens immediately beyond the Miller’s tenant holding. He has six daughters.”

His eyes narrowed and Jacaranda found her crepe wasn’t merely good, it was delicious.

“I have a taken a viper to my bosom.” Mr. Kettering slathered butter on a piece of toast, then jam, then sliced it in half and put a triangle on Jacaranda’s plate. “Six daughters?”

“The Damuses have eight girls but only two are marriageable age.”

“We’ll start with the Damuses,” he decided. “You will join me for breakfast regularly. I’ll need your familiarity with the locals to plan the girls’ social calendar.” He bent to take a bite of his toast, while Jacaranda was sure he was hiding another smile.

He’d cornered her neatly, making her attendance at breakfast a show of consideration for the children, not an order.

“I will join you for breakfast.” She took another bite of crepes, so light they nearly levitated off of her fork. “And only breakfast.”

“Oh, fair enough, for the present. Now finish your crepe, Wyeth. I’ve notion to look at that bump on your head.”

“No need for that.” She took a bite of heaven and chewed carefully. Even crepes required some mastication and the effect was to pull on that region of her head still lightly throbbing.

“You’ve put every bite to the same side of your mouth, my dear. It’s paining you. Did you sleep well?”

“I did. I usually do.”

“I usually don’t,” he said, frowning at his tea cup.

“Perhaps the country air will agree with you.” She’d meant to say it maliciously, because he was so great a fool as to think correspondence from Town more important than a newly discovered sister.

“Intriguing thought. So what would a conscientious land owner do, were he facing my day?”

Papa had been nothing, if not conscientious about his acres, and Grey followed very much in Papa’s footsteps.

“A conscientious landowner would ride out. He might take his land steward, particularly after an absence, or take a few of his favorite hounds. He’d look in on his tenants, especially those with new babies or a recent loss.” Or he’d take his sons, and the house would, for a few short hours, be blessedly peaceful.

“I like babies.”

Oh, he would.

“Will my steward know of such things? Babies and departed grannies?”

“The Henderson’s lost a child this spring, a bad case of flu,” Jacaranda said pushing her plate away a few inches. “A little girl named Linda. I believe she was four and had always been sickly, but they’d got her through the winter and were hoping she’d turned a corner.”

He took a bite from the half crepe she’d left on her plate, chewed and arranged his fork and knife across the top of the plate. “And you want me to call on these people?”

“I’ll pack you a hamper. They’ve many mouths to feed.”

“I can’t ride over with a hamper on Goliath’s quarters.” He lifted his tea cup, examined the dregs, set it down. “Come with me?”

A request, not an order. “To call on a tenant, I can accompany you. Their wives will be glad of another woman to chat with.”

“You know their wives?”

“When your tenants have illness or particular needs they send to us here and we provide what aid we can. The English countryside remains a place where one’s neighbors are a source of aid, and course I know their wives.”

“So where else do I need to show the flag?”

“These calls, the first you’ve made in years, aren’t showing the flag.” She regarded him with some displeasure, for the crepes had been very good, while the company was vexing. To deal with this man, she’d need her strength. “These people labor for your enrichment. Their welfare should concern you.”

“It should,” he agreed easily enough, but Jacaranda had the sense his wheels were turning at a great rate mentally. “Let’s have a look at that knot on your head, hmm?” He rose and stood beside her chair, prepared to hold it for her, as if she were… a lady.

She did not fuss him for that, for something warned her he’d love nothing more than fussing right back while he stood over her, first thing in the day.

“Over by the window.” He drew her to her feet and tugged her by the wrist to the light pouring in the east-facing window. “Turn yourself, just…” He took her by the shoulders and positioned her to his liking. “Like that.”

When he stepped close, she got a fat whiff of delicious, clean man. He used some sort of shaving soap that made her want to lean closer and intoxicate her nose on his woodsy scent. And the scent had little spicy grace notes as well—even his scent held unplumbed depths.

“You must have a busy day of your own,” he suggested, carefully tilting her head in his big hands.

“Industry is its own reward.” But he had offered the gambit to distract Jacaranda from his fingers tunneling through her hair and that was decent of him, so she rallied her manners. “In truth, I have done as much preparation for your visit as I possibly can, but the house is always kept in readiness, so the burden of additional work is not great.”

“Then you might enjoy coming along with me on these tenant calls?” Gently, gently, Mr. Kettering moved his touch over the knot at her temple. “Hurts, doesn’t it?”

“A little.” While his touch was lovely.

“The bleeding did not resume,” he said, slipping his fingers from her hair, but not stepping back. “I’m glad you won’t mind showing me about the farms.”

He was smiling down at her again, pleased with himself, the lout.

“That’s not what I meant.” She was prepared to launch into a clarification, but he patted her arm.

“We’ll wait until after lunch, so I can fire off a few letters first, otherwise I’ll never be up to dandling babies and pinching grannies.”

“Please say you would never pinch a grandmother!”

Now he did step back, his eyes dancing.

“My dear Mrs. Wyeth, I would pinch a granny, but only because she pinched me first. I know a number of grannies who aren’t to be trusted in this regard. They’re a shameless lot, for the most part. Complete tarts. Shall we say one of the clock?”

“I’ll have luncheon moved up to noon,” she said, not taking the bait no matter how succulent, no matter how close to her nose he dangled it while looking the picture of masculine innocence. “In deference to the fact that they traveled for much of the day yesterday, I’ve planned luncheon as a picnic meal on the back lawn for your sister and your niece.”

“I’m dining on the ground with children, being pinched by grannies, and acquiring hounds, and you expect the country air to agree with me? You are a cruel woman, Jacaranda Wyeth. I’ll meet you at the coach house at one.”

![]()

“So how are you ladies settling in?” Worth put the question to his sister and his niece, who looked quite pleased to be eating outside, with bugs and breezes and not a table cloth in sight.

Avery, as was her habit, went chattering off in French, lightened by a dash of Italian, with the occasional foray into her expanding English vocabulary. The coach ride had been interminable, the horses were very grand, but not as grand as Goliath, the coach fare had been very good if difficult to tidily consume in a moving vehicle, and Miss Snyder had been as quiet as a moose.

“Mouse,” Yolanda corrected, smiling—the first time Worth had seen that expression on his sister’s face.

“What is the difference? Mouse, moose, you know I refer to a little creature for the cat to eat.”

“There is a difference,” Yolanda said. “Worth, have you pencil and paper?”

He passed over the contents of his breast pocket and Yolanda started scribbling.

“Where have you seen moose, Yolanda?” he asked, selecting a cold chicken leg to gnaw on.

“In books, unless you count Harolda Bigglesworth. Poor thing had a name like that and dimensions to match, but she was very merry.”

“Shall we invite her out to the country with us?” Worth had to admit the chicken was delicious, and with a napkin wrapped around one end, not so very messy.

“We shall not,” Yolanda said as she sketched. “She’s been engaged to some viscount since she was a child and association with the likes of me would not do.”

“Your brother is a perishing earl.” Worth waved his chicken leg for emphasis. “Why not associate with you?”

“Your moose,” Yolanda said, passing the sketch pad over to her niece. “He’s a grand fellow, nigh as big as Goliath and he lives in the Canadian woods.”

“My goodness, he looks like a cross between a cow and a deer, but what a nose he has!”

Worth peeked over Avery’s shoulder.

“You are talented,” Worth said. “Talent is worth money you know. I have a client who will make a tidy living painting portraits, a very tidy living. You should develop your art Yolanda.”

“Drawing is one thing they let you do,” she said, shrugging her shoulders.

“They let you do?” Worth set aside the chicken bone, for he’d eaten every scrap of meat on it.

“When you’re on room restriction, at school, you can have your school supplies to entertain you, but only those, so I drew a great deal. Avery, will you eat every bite of that potato salad?”

Avery made Yolanda earn her salad by teaching her a half dozen German words. Yolanda made Avery try to copy the moose, with comic results. All in all, it was a pleasurable, nutritious way to pass an hour with his…. Family, out of doors. On that thought, Worth pushed back to sit on his heels.

“My dears, I must away to impersonate a country squire. If you like I can ask the neighbors if any ponies are going begging in the surrounds.”

“Oh, Uncle!” Avery’s jubilation at the prospect of a pony knew no linguistic bounds, but Yolanda merely smiled at her niece and toyed with a bite of cheese.

“Yolanda? What say you? Shall we find you a gallant steed so you can gallivant about the countryside and turn all the lads’ heads?”

Yolanda studied her cheese. “Good heavens, no thank you. I’ve heard riding can make a girl’s figure lopsided.”

“So we’ll teach you to drive,” Worth suggested, “or fit you out with a left-side saddle, and a right-side saddle and you can alternate.”

“That’s what I shall do,” Avery interjected. “And I shall ride with Uncle every day.”

Uncle drew a finger down her nose. “No you shall not. This is England, and it rains too frequently for that. Well, think about it, Yolanda. I must call upon the neighbors, many of whom are possessed of offspring whose acquaintance you should make. We’ll be here for months and I can’t have the two of you getting lonely.”

He got to his feet and made for the coach house, but the meal, surprisingly pleasant though it was, had left him more convinced than ever that Yolanda was hiding a great deal.

![]()

“Tell me about these Damuses,” Worth said as they tooled out of the coach yard. Goliath—trained to drive as well as ride, like any proper mount of his dimensions—was in the traces, which had required loosening the harness by a few holes in all directions.