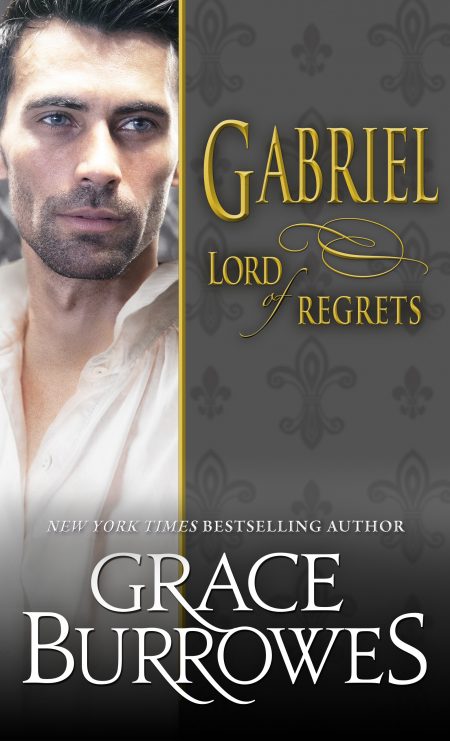

Gabriel

Lord of Regrets

Book 5 in the Lonely Lords series

Gabriel North has spent two years allowing his family to believe him dead, while he assumes the identity of a hardworking steward on the neglected Three Springs estate. When Gabriel falls in love with Polonaise Hunt, cook at Three Springs, he realizes he must solve the mystery of who tried repeatedly to kill him, before he can ask any woman to share his life.

Gabriel resumes his proper identity as Marquis of Hesketh only to find that Polonaise has also resumed her calling, that of talented portrait artist, and she’s been commission to paint Gabriel’s heir. While Gabriel tries to untangle the mystery of his attempted murder, he finds Polonaise has been keeping secrets of her own. She can capture Gabriel’s likeness on canvas, but can he capture her heart?

Bonus Materials →

Enjoy An Excerpt

Chapter One

“It’s time I rose from the dead.”

The Dowager Marchioness of Warne eyed her guest placidly over her teacup, despite the impact of his words.

Oh, to be thirty years younger—even twenty. “Is that wise, Gabriel? You never did get to the bottom of all that mischief in Spain.”

Gabriel Wendover rose to his considerable height and paced to the window overlooking the back gardens. “Here’s my dilemma: My younger brother is one of few who can convincingly identify me. If I don’t emerge from my convalescence now, Aaron could well drink himself into oblivion, or engage in one too many duels, and then I’m an opportunistic poseur, trying to do battle with Prinny’s legal weasels.”

“Surely your former fiancée could identify you.” Lady Warne enjoyed the view of her guest from the back almost as much as she did from the front. He was all lean, elegant muscle now, though two years ago he’d been at death’s door.

“I’m not sure I’d trust Marjorie that far.” Gabriel turned away from his study of the flowers. “As Aaron’s wife, and the Marchioness of Hesketh, she now commands significant wealth and respect. If she’s simply the wife of a younger son, she gets a great deal less.”

“But an adequate portion to survive on?”

“Of course.” His features shuttered, and an idea popped into her ladyship’s mind.

“Does this sudden urge to come out of the shadows have to do with a woman, Gabriel?”

Not by the flicker of a dark eyelash did he betray any reaction to the question, and in his stillness, Lady Warne found a hint of confirmation that she’d guessed correctly.

“Why would you suggest that?”

She went to stand beside him, close enough that the afternoon sun revealed fatigue around his eyes and mouth. “Two years ago, you were done searching for justice, done trying to figure out who wished you dead. You took over stewarding Three Springs for me, and despite all odds to the contrary, you made it prosper. I thought you were content there and would finish out your days as plain Gabriel North, humble, if taciturn, land steward.”

“Taciturn?”

“Reserved.” And because he was less than half her age, she allowed herself a smidgen of fun at his expense. “Brooding.”

“I was recovering from a mortal wound. This does not incline a man to a sanguine demeanor.” He fell silent. He was too dear a man, and she was too old not to wait him out. “My decision doesn’t have to do with a woman, but rather, with the absence of a woman.”

He was lonely, and he’d been lonely when they’d met two years ago, though it appeared he was now becoming aware of this sorry state of affairs. And when Gabriel Wendover saw a problem, he must needs address it.

“Surely, with your looks, you don’t lack for female company?”

“And all my wit and charm?” He raised an eyebrow, and Lady Warne was put in mind of those ancient, rousing days when a man took by conquest and held by main strength. Gabriel would have prospered then, too—handily—and likely had his version of fun, bashing heads and bellowing war cries.

“You’re as charming as you need to be,” she observed, “though you don’t prevaricate any better than my grandsons do.”

His brilliant green eyes showed some emotion, humor perhaps, but so briefly that Lady Warne couldn’t be sure of what she’d seen.

“As long as I turn my back on my birthright,” he said, “I am unable to marry, unable to even dally, really, because I’m living a lie.”

Clearly, Gabriel had never moved about much in society. “Dallying men are supposed to lie. It’s part of the consideration due the ladies.”

“Then I’ve lost the knack of dallying, if I ever had it.” He crossed his arms over his chest, a gesture that to her ladyship looked more defensive than stubborn. “I can’t risk that a woman close to me could become a victim of the same kind of violence that befell me, or see her used somehow as leverage against me.”

“You’ve been brooding on this.”

“Considering,” he allowed. “I cannot resign myself to watching Aaron fritter away the family fortune, much less fritter away his life, so Prinny can snatch up the rewards when escheat befalls the title. If I’m going to be dead, I’d rather die battling my enemies than of mortification at my younger brother’s moral collapse.”

“He is young,” Lady Warne pointed out. Everybody was young to her these days. “Maybe he’ll come right if you give him a few more years.”

“The longer I wait, the less credible any story of protracted delirium or lost memory becomes.”

Gabriel was not merely lonely; he had fallen in love. The notion was startling and gratifying, and the only possible explanation for a radical departure from his well-laid, ridiculous plans of two years ago. “Maybe you were captured by gypsies and held as a prisoner until the gypsy princess fell in love with you and set you free.”

His answering scowl was ferocious.

“What have I said?”

“Sara Hunt was known as the Gypsy Princess when she toured the Continent.”

“She’s Lady Reston now.” May God and a handsome grandson be thanked. “Married to my dear Beckman, and no longer a traveling musician playing for coin, or the lowly housekeeper raising her daughter at Three Springs. Beckman is arse over teakettle for his lady wife.”

Gabriel flashed her a rare, precious smile. “My virgin ears. Such language.”

“Your ears are no more virgin than your… the rest of you. What can I do to help?” Because she would help, will he, nil he.

“Ask your spies what they know about the goings on at Hesketh,” Gabriel said. “I know of three duels Aaron’s been involved in over the past twelve months. I hear of particularly wicked house parties with his army cronies when his wife is up to Town, and Marjorie’s bills would finance a cavalry unit and their mounts. This makes no sense to me. Aaron was fun loving, not reckless, and he was raised as the spare. He should know how to go on better than this now that he’s Hesketh.”

“Your papa’s death was unexpected, as was your so-called demise,” Lady Warne reminded him. “Men can misbehave badly when a title befalls them on short notice.”

“So one hears.”

“I’ll listen to the gossip, but you’re going to need allies if you intend to march off smartly to Hesketh and declare yourself alive and well.”

“I can’t ask others to put their lives in jeopardy merely because I’m feeling possessive of my title.”

“Not possessive, protective.”

“Both. I have one other favor to ask of you.”

“Anything.”

He looked momentarily nonplussed by the immediacy of her answer, and that gave her satisfaction. The man had been alone too long, probably since before his injury in Spain.

“I need a place to stay, somewhere nobody will think to look for me over the next week or so.” He was gazing out over the asters and chrysanthemums again, his expression distant. “I must dress the part if I’m to make a grand reentrance at Hesketh, and I want to do some loitering in low places before I go home.”

“You want to make the rounds.” She looked him over, seeing the dusty boots, the threadbare morning coat, the cravat that sported not a hint of lace. “Gather intelligence. You are more than welcome to stay here, young man, but you’ll tell me what news you come across, and I’ll do likewise.”

“My thanks, and my lady?”

“Hmm?”

“Be careful. Beckman, Nicholas, and the rest of your tribe of grandchildren would flay me where I stood did I bring harm to you.”

“Having a little project is more likely to keep a woman of my age out of trouble, I’ll have you know. Now, if you want to restore your wardrobe, you will take my advice, for the tailors gossip as freely as the modistes.”

“I’m listening.”

Having made his request of her, he visibly relaxed, lounging back against the windowsill as they plotted and planned.

Oh, to be thirty years younger. Even twenty.

![]()

“You’ve eight commissions.”

“Eight!?”

How it gratified Tremaine to see the incredulity on Polonaise Hunt’s lovely face. “I accepted only eight, but I could have come away with twice that number.”

The smile trying to break across Polly’s face dimmed. “Do they know the artist is female?”

“They don’t care.” Which was the God’s honest truth, not that Tremaine would attempt to dissemble. “They don’t care that you may take three years to execute their various portraits; they don’t care that you’re going to bankrupt them for the privilege of waiting for you. All they care about is being able to crow that P. Hunt is under contract to them.”

“Eight commissions.” Polly sank down on a red velvet settee and wrapped her arms around her trim middle. “Heavens.”

“And, my dear”—though she wasn’t his dear; she was his late brother Reynard’s sister-by-marriage, nothing more—”your show sold out.” He appropriated the spot beside her on the sofa, contenting himself with physical proximity.

“Sold…” Polly stared hard at the carpet, as if a pattern woven in red, gold, and cream wool required study. “People bought my paintings, just like that?”

“They tried to bid on them. Next time, we’re having an auction.”

“Next time.” Polly hunched forward, the look on her face suggesting she’d forgotten Tremaine and her eight commissions, and was instead seeing paintings and arranging her subjects.

He touched her hand. “Does this call for a drink?”

“Just a tot. Years in service at Three Springs leaves a woman with little head for spirits.”

“I had a letter from Beckman today.” Tremaine brought her a balloon with the merest slosh of amber liquid in the bowl. Polly Hunt said what she meant and meant what she said. If she’d wanted a larger portion, she would have told him.

“How fares my sister’s present spouse?” Polly took the drink and brought the glass to her nose, a facial feature that might be said to have character. Tremaine liked that nose, and liked her, more’s the pity. He’d liked her the first time he’d encountered her nearly six years ago, wearing a paint-spattered smock and an impatient expression.

Dear Reynard had stashed both his wife and her younger sister in a rented flat in Vienna. The air had been frigid, the scent of boiled cabbage gaggingly thick, but all Tremaine had noticed was the dab of blue paint on Polly’s nose and the ferocious concentration she’d turned on her canvas within two minutes of meeting him.

He resumed his place beside her. “Your sister is thriving in Beck’s care, the harvest was excellent, that peculiar wheat of Beck’s is coming along, and they’ve a crop of fall lambs from the Dorset rams.”

“Lambs? Sara married a country squire it seems.”

“Who will tell anyone he meets that his wife’s sister is the renowned—and wealthy—portrait artist Polonaise Hunt.”

“Wealthy.” Polly smiled softly, and Tremaine took a fortifying swallow of his drink. “How wealthy, Tremaine?”

He named a figure that had Polly’s jaw dropping, then snapping shut.

“I’ll need a solicitor,” she said, “and I want to set up a trust, for Allie.”

He had not anticipated this, but he should have. “Sara and Beck provide for her very well, and the first person you should be looking after is yourself.”

“I am Allie’s only aunt, the person with whom she shares artistic talent. The wealthy, famous, and all-that-other-nonsense-you-said P. Hunt can dote on her niece.” Polly wasn’t a tall woman, but when she rose, she had an imposing presence. Whereas her sister, Sara, was tall with flame-red hair and lithe curves, Polly was a smaller package, her hair a dark auburn and her curves—like her nose—more pronounced.

“Allie is part of the reason I’ve scheduled your first commission down by Portsmouth,” Tremaine said, dodging the issue. Polly was Allemande’s aunt, and Tremaine was her uncle—he knew well the urge to spoil the girl.

Polly leveled a stare at him that did not bode well for prevaricating males of any species. “A solicitor, Tremaine. The most shrewd, accomplished, expensive one you can find me.”

He poured himself more brandy. Since he’d undertaken to act as agent for Polly’s art, Tremaine’s consumption of spirits had risen while his quotient of restful sleep had diminished. “Worth Kettering is your man, if he’ll have you.”

She ceased her pacing near a small framed portrait of a dark-haired, dark-eyed young mother with a laughing infant on her lap. “Why wouldn’t he have me?”

“He’s selective about his clients, and his firm is much in demand. I use him, but I have for years, and it suited him at the time to have an errant French comte wandering his offices.”

“Half-French, half-Scottish,” Polly muttered. “This truly is a delightful painting, Tremaine. The brushwork is lovingly rendered, and the light wonderfully delicate. Will Mr. Kettering not take me on because I’m female, or because I’m an artist? Or will it be because I lack a title?”

“I’ll write him. I think he will take you on.”

She adjusted the angle of the frame minutely. “Why?”

“Because you need him.” And Kettering had not a chivalrous streak, but a chivalrous quirk, such that Polly’s circumstances would appeal to him.

“Because I’m wealthy,” she concluded, stepping away from the portrait. “I need him because I’m wealthy. Tell me about my first commission.”

Safer ground, and he hadn’t even had to maneuver her onto it. “It’s at Hesketh, which is only about a day’s ride from Three Springs, and thus close to Allie.”

Polly turned velvety brown eyes on him, and Tremaine couldn’t help reaching out to tuck a lock of hair behind her ear. “For letting me start out near Allie, Sara, and Beck, thank you.”

“I put Hesketh at the front of the line for another reason.” Besides the need to put some distance between himself and his talented client. “Aaron Wendover is a damned good-looking devil. You won’t have to flatter or artistically interpret his features to create something of significant aesthetic appeal.”

Polly resumed studying the picture of mother and child. “And his lady?”

“Also lovely, to the eye.”

She shot him a peevish look. “Tell me the rest. An artist must capture more than a pretty face and a pretty gown.”

Tremaine wished, not for the first time, that he had artistic talent himself, though it wasn’t some titled ninnyhammer he’d try to render on canvas.

“You’re a scandalmonger, Polly Hunt. As bad as Beck’s grandmother, who sent all her wealthy friends to your showing, by the way.”

“Then we must call on her when you take me up to Town to meet that solicitor,” Polly said. “I’ll write her a note as soon as I’ve choked down the miserable fare your cook inflicts on you. I swear, Tremaine, how you keep meat on those enormous bones of yours defies science.”

“I am sated on the beauty of my female relations.”

Polly smiled at that twaddle, clearly not at all impressed with supercilious flattery, and no doubt telling herself Tremaine was, after all, half-French.

![]()

“It’s as if God took Reynard St. Michael,” Polly mused to her sister, “and formed his brother, Tremaine, into his opposite.”

“Half brother.” Sara went about the Three Springs kitchen, collecting the detritus of one of Polly Hunt’s baking sprees. “And being Reynard’s opposite isn’t entirely a bad thing. I know Reynard was Allie’s papa, and we must always be grateful for her, but what, exactly, were my late husband’s good qualities?”

Polly paused while stirring a bowl of chocolate icing. “He was canny as hell,” she decided, “and Tremaine does share that feature.”

“Which makes him a good manager for your painting, provided he’s honest.”

“He’s honest, and too quick by half.”

“Too quick?”

“He proposed to me, Sara.” Polly recommenced whipping the daylights out of her frosting. “We had just come from the solicitor’s office. Tremaine put it in the most polite, bored, business terms—to allow me to sport a ring, to fend off the wandering hands of clients and their younger sons, to quiet talk about our business association—but he allowed me to understand, should it suit me at some point, we might discuss actually marrying.”

“You were tempted.” Sara paused, her hands full of dirty crockery. “Oh, Polly.”

Polly went at the frosting with a vengeance. “Yes, oh, Polly. He can see I’m pining for a man, and he’s thinking to take advantage.”

“Maybe he can see you’re pretty, talented, lonely, and in need of some roots,” Sara said. “I wish you’d stay here, Polly. You can paint anywhere. You don’t need to become a gypsy for your art.”

“One gypsy princess in the family was plenty?”

“Shame on you,” Sara chided, but without heat. “Allie misses you.”

“And I miss her, which is a good thing, Sara. If we hadn’t struck out on separate paths, I might never have realized I do miss her.”

“How could you not?”

“I miss North almost as much,” Polly said, her frosting fork going still again.

“Beck thought maybe that’s why you needed a change of scene.” Sara set the dirty dishes in the sink. “You have a lot of memories of Gabriel here at Three Springs.”

“Right.” Polly used a butter knife to dab frosting on a pale yellow cake. “Memories of Gabriel getting up while I mixed the bread dough, Gabriel heading out without a proper breakfast unless I forced it on him, and Gabriel coming in exhausted right as dinner was put on the table. Memories of Gabriel avoiding me.”

“I thought you two had reached some sort of accord before he left here.” Sara turned her attention to wiping down the counters, which were spotless. “For the last few months, that is, but then, I was preoccupied with Lady Warne’s handsome grandson and Tremaine’s looming presence.”

“We reached…” Polly dabbed the pattern of a flower into the frosting: a rose. “We reached an agreement to disagree. I think he left in part because he couldn’t stand to see my disappointment.”

“Or because,” Sara said gently, “he couldn’t trust himself not to take advantage. Gabriel is a gentleman.”

“Titled.” Polly surveyed her work, then smoothed the flower away. “He told me that much, but he also told me his family, or somebody, did not want him to survive to perpetuate the line, and Gabriel could not endanger a lady closely associated with him. Not for anything.”

“He wouldn’t let Hildegard suffer a sniffle on his behalf, could he avoid it. Allie considers him honorary godparent to all of Hildy’s piglets.” Sara scrubbed the counter with particular force. “So he’s gone.”

“To parts unknown.” Polly glowered at her cake. “Dratted man.”

Sara glanced at the door as if expecting menfolk to appear now that the cleaning up was done. “Beck had a note from Gabriel today, and it seems he’s a guest of Lady Warne for the present, but he made no mention of his next destination.”

“He said he wouldn’t.” Polly drew the confectionary rose into the frosting again and addeda few thorns. “And no mention of me, either, did he?”

Sara crossed the few steps to hug her sister. “You’re not going to accept Tremaine’s silly proposal, are you? He means well, but guilt and a broken heart are no way to start a marriage.”

![]()

“You said you’d be decent to our guest,” Marjorie accused. “You’re not even going to be here to greet her.”

“I’ll see her at dinner,” Aaron replied, his patience fraying the longer he stood in the foyer and argued with his wife before the servants. “George says we’ve a problem with one of the hay barns, and it won’t keep. Unless you want all your pretty carriage horses to live on good intentions this winter, you’ll make my excuses to this artist.”

“Miss Polonaise Hunt,” Marjorie said tightly. “Go then, but if George can’t solve the problems with the estate farms, then why are you paying him to serve as steward?”

“Good day, Marjorie.” Aaron gave her a curt bow. “I’ll see you at dinner, along with Miss Hunt.”

He stalked down the front steps, glad for any excuse to leave the house, but he had to concede that Marjorie, as usual, had a valid point. George Wendover had been the steward for years, for pity’s sake, and with his fat salary and cozy house came the job of running the tens of thousands of acres held both through the Hesketh title and privately by the Wendover family.

But everything, everything, seemed to require Aaron’s personal attention, because dear Cousin George never wanted to overstep or make a controversial decision. He was loyal, was George, but something of a ditherer in Aaron’s opinion. George was also a distant cousin, though, and Aaron’s father had trusted the man, as had Gabriel, so Aaron gave him his due.

“It’s the last of the hay put up,” George explained. He stood in the hay barn, an enormous structure set into the side of a hill, with room for beasts below, and three high mows in the upper part of the building. “Mold got to it, but we’re only finding it now, as we’re beginning to feed some of the fodder on the colder nights.”

“Mold?” The hay barn was well ventilated, of that Aaron was certain. “We had good haying weather this year. I know we did. None of that hay should have been put up wet.”

George was intent on studying the barn’s roof beams, though they’d likely occupied their present positions for more than a century. “Must have been wetter than we thought, or it got wet, but the roof is tight, so that makes no sense.”

“How much is ruined?”

George nodded at the nearest third of the barn. “That mow seems to have got the worst of it, but you’re right. Haying was good this year, so there should be hay to purchase.”

“Buy what we need, and sell some of the straw. This lot can be used as bedding hay, at least the parts not completely rotted.”

“Bedding hay.”

George had a way of repeating what had been said that made Aaron want to throttle him. “Lousy hay, not fit for eating, isn’t that what you call it?”

“Mostly, we call it kindling.”

“If it’s not moldy, it has some value,” Aaron argued, “so use it as bedding. If there’s decent fodder to be had, the animals won’t eat the sorrier alternative.”

“If you say so.” George’s features remained impassive as he resumed his study of the beams, and curses learned in the cavalry flitted through Aaron’s head. George never disagreed with Aaron but he never quite agreed with him either.

“George,” Aaron kept his tone patient, “what would my father have done?”

“He’d not have put up wet hay.”

Do not curse at a man who’s trying his best, and is a relation as well.

“Not on purpose, but say a tree fell on the barn roof and a rainstorm got to some of his hay, what would he have done with it?”

“He wouldn’t have allowed trees of such a size near his barn.”

Aaron gave up on parables. “Sell some of the barley and oat straw, and get us more hay. Was there anything else you wanted to discuss?”

He knew better, knew better, than to leave George such an opening, because there was always, always, something else. This cow had a bad foot, that mare hadn’t caught, and the chickens weren’t laying as well as they had last fall.

None of which, in Aaron’s opinion, merited the attention of the Marquess of Hesketh. Such trivialities took all afternoon, meaning correspondence would have to be dealt with far into the night, and damn and blast if he hadn’t promised Marjorie he’d appear in proper attire at dinner.

Damn Marjorie for her insistence on having portraits done.

Damn the hay for turning moldy.

And most of all, damn Gabriel for dying.

![]()

Gabriel had spent months envisioning this day, months plotting exactly what dramatic, pithy, unforgettable line he would recite when his brother beheld him risen from his supposed grave. In hindsight, he saw his months of rehearsal were merely the mental posturing of one victimized by violence, seeking reassurance from his imagination when it wasn’t available elsewhere.

So he handed his horse off to a groom he didn’t recognize and took himself into the stables to use the mirror hanging in the saddle room, a vanity their grandfather had insisted on fifty years ago.

As Gabriel was inspecting his tired, dusty, and frankly unappealing reflection, Aaron came into the saddle room, muttering about it being impossible to find a damned jumping bat when a man needed one and owned at least ten, and where in the hell—

In the mirror, Gabriel saw the moment his brother spied him, the moment recognition tried to force its way past disbelief.

“Gabriel?” Incredulity, but also hope, relief, and genuine, unmistakable joy colored that one word. Gabriel turned, the same emotions crowding into his throat and chest as his brother hurtled into his arms.

“Damn you, damn you,” Aaron whispered fervently. “Just damn you to hell, damn you to goddamned, bloody, benighted, stinking, perishing hell. You’re alive.” He fell silent, hugging Gabriel in a crushing embrace, until he stepped back, balled up a fist, and flashed a lightning quick right to his older brother’s chin.

Then wrapped him in another suffocating hug.

Gabriel had anticipated the blow, but it still stung, leaving a reassurance as the pain dulled to a throb, but reassurance of what, Gabriel didn’t know. That he was loved, maybe? That his brother wouldn’t have connived at the title to the point of having Gabriel murdered—maybe?

Aaron held him at arm’s length, looking Gabriel over with a scowl reminiscent of their late father.

“I am happier to see you than you can possible know, but, Brother, you are in a bloody lot of trouble.”

“One suspected this would be the case. You look like hell yourself.”

“Married life does not agree with me,” Aaron shot back. “Nor does wearing your idiot title, nor does sitting on my arse in the library hour after hour and bickering in writing with doddering lords trying to cadge my vote on every worthless bit of self-enrichment they can legislate.”

Aaron had always had a temper, a quick tongue, and an equally generous and forgiving heart. In the two years since Gabriel had last seen him, though, Aaron had laid claim to the essential darkness of demeanor previously reserved for every other male member of the Wendover clan.

In short, Aaron had grown up, and this left Gabriel feeling both sad and guilty. They were five years apart in age, though sometimes, it had felt closer to fifteen.

No more.

“Let’s get you up to the house,” Aaron said. “Will you have luggage coming along soon?”

“I have only what my horse could carry, though there will be more coming down from London eventually.”

“Is that where you’ve been hiding?” Aaron’s tone held a hint of that hard blow to the chin.

“Walk with me.” Gabriel took charge of their progress toward the house, and led his brother around to the side gardens, where plane maples provided shade, beauty, and more importantly, privacy.

Aaron had also apparently learned some patience, or some strategy, because he kept his peace until Gabriel found them a bench under the trees, out of sight of the house or stables.

“We never did get to the bottom of my mishap in Spain.” Gabriel sat slowly, the damned English roads having wreaked havoc with his back for the last ten miles. Aaron tossed himself onto the bench with casual grace.

“Mishap?” He snorted. “You were set upon by brigands, as often happens to men traveling alone in war zones after dark.”

“It wasn’t a war zone, Aaron. We were well behind the lines, and I was traveling between the church and the infirmary where you were recuperating. I traversed the middle of the village under a full moon.”

“I was dying,” Aaron said tiredly. He crossed his legs at the ankles and leaned back to turn his face up to the sun. “You were set upon while I lay helpless, and if you’d stayed in England, you’d still be… well, you are, alive… Christ.”

“You weren’t dying.” Though in the bright sunlight, Aaron now looked to be at least exhausted. “You’d given up, and because the army knows nothing of medicine save cutting, burning, stitching, and praying, you needed better care. You were too stubborn to trade on the family name, so you weren’t getting that care, hence the necessity of my travel.”

And hence, indirectly, two years of backbreaking labor and heart-wrenching uncertainty as well, for them both—and for Marjorie?

Aaron swung at a bed of yellow pansies with his riding crop, missing—fortunately. “What’s your point?”

“I had no money on me,” Gabriel said. “I was on a humble borrowed army mount, and yet, I am larger and meaner and fitter than most—or I was. I do not think brigands set upon me.”

“The men and I asked around everywhere, Gabriel,” Aaron countered. “Nobody had heard the least rumor that you were ambushed as anything other than a casual crime.”

“You asked around in English. Even if I allow that the first attack was pure bad luck, what about the second and the third?”

Aaron hunched forward, resting his forearms on his thighs and sending Gabriel a puzzled glance over his shoulder. “The second being whoever tried holding a pillow to your ugly face when I was finally recovered enough to leave you to the sisters. I know nothing of a third.”

“The fire,” Gabriel said. “The one that supposedly took my life. I was given laudanum for the pain in my back, but I’d mostly weaned myself rather than let it become a dependency. I wasn’t fast asleep as intended when somebody torched the infirmary—I wasn’t even in my bed.”

“You were off trysting?”

Had Aaron developed a penchant for trysting despite being married to Marjorie? Was that what all her shopping and his dueling were about?

“I was taking a damned piss,” Gabriel shot back. “And there but for the grace of God, I’d be sporting that halo.”

“So you went into hiding,” Aaron surmised.

“I am willing to be convinced that my death was not planned, but who among the Spanish, English, Portuguese, or French would torch a convent’s infirmary? Too many wounded and ill depended on the kindness of the sisters, and they took in their patients regardless of nationality.”

Aaron swatted at nothing with his crop, while Gabriel felt his brother putting together puzzle pieces. “By the time you were well enough to come home, I’d had you declared dead, and you suspected I was behind all the attempts.”

Gabriel rose carefully—now was no time for his damned back to seize up—and paced off a few feet. They were surrounded by pansies and chrysanthemums, though a few precocious maples were parting with their leaves. The garden in all its autumn glory was easier to look upon than Aaron’s face.

“I didn’t want to think you guilty, Aaron. You were the only one with anything to gain, and then too, I lay in that damned bed for months, thinking myself into a stew, and your guilt was the logical conclusion.”

“Is it still?”

And there, in a nutshell, was why Gabriel loved, and despaired of, his brother. Aaron was brave, unflinchingly courageous. He’d toss out a question like that, knowing it opened an unbearably painful wound for them both. And he’d do it without batting an eye. Such a man might easily believe himself to be—and might be—the better choice to hold the title.

“No, it is not the logical conclusion,” Gabriel said, turning in time to see his brother’s shoulders drop, the only sign Aaron had given a damn about the answer, one way or another. “It’s no longer the only possible conclusion.”

“Oh, famous.” This time, Aaron decapitated a few pansies with his crop, and the steward in Gabriel winced. “A Scottish verdict? Insufficient evidence?”

“No evidence,” Gabriel said, eyeing the pansy parts scattered on the ground. “My own fevered reasoning, but no evidence and plenty of reasonable doubts.”

“Such as?”

“You didn’t know I was coming to fetch you home.” Gabriel resumed his seat beside Aaron, though the hard bench was murder on an aching back. “It’s easy enough to have a man killed if you’ve coin and cunning. If you’d wanted me dead, it would have made more sense for you to see the thing done while you were in Spain and I was in England.”

Aaron left the bench, reminding Gabriel that his brother had never enjoyed inactivity. “If I’d wanted you dead, I would have managed it myself on a field of honor, regardless of country.”

“May I assume that isn’t a challenge?”

Aaron scrubbed a hand over his face. “Don’t be ridiculous, but if I were you, I wouldn’t turn my back on Marjorie anytime soon.” The smile accompanying this advice was complicated: humorous, rueful, self-mocking. Boys did not smile like that, though married men did.

“I assume Marjorie is well?” Gabriel shifted on the infernal bench and missed the padding Polly had kept on his chair at the Three Springs kitchen table.

Missed Polly too, though that was hardly news.

“Marjorie’s not breeding, if that’s what you’re asking. She’s utterly miserable married to me, and lest there be any doubt, long lost brother, I am miserable married to her. It’s the English way. She’s hired a portrait artist to memorialize our misery.”

Perhaps Aaron wanted to call him out after all? “You didn’t have to marry her.”

“Yes, Gabriel, I did. Her dear mama was crying breach of promise and damages if I hadn’t, and your Mr. Kettering was very reluctant to hand over the details of the agreement to a mere wastrel younger brother when you were yet alive.”

Damn Worth Kettering and his lawyerly scruples. “You had me declared dead just to get a look at the contract?”

“No.” Aaron slapped his crop against his boot, and a leaf went twirling by, as if the crop were a magic wand that might bring the heavens crashing down with the right incantation. “I had you declared dead so that, having no other plan in hand, I could try getting on with your life.”

![]()

Gabriel wandered every wing and corridor of his former home—his home—saving the portrait gallery for last, because to him it was the heart of the Wendover family seat. Of the barons, three in number, there were no paintings, not even sketches, but when a grateful crown had created the Earldom of Northbridge, that good fellow’s countess had taken matters in hand and set the Wendovers on the tradition of portraiture.

Gabriel studied the portrait of him and Aaron for a long time, seeing the hubris of a wealthy heir in his younger self. God in heaven, he’d had a lot to learn.

Something made him turn, to watch the afternoon light cascading through the spotless windows. Polly had loved the fall light, calling it frisky.

He put that thought aside. A man was not entitled to dwell on a woman he’d loved and lost, much less one he’d disappointed in the process, and this gave the ache of missing her a particular resonance. He thought to bide a few minutes among the ancestors and guiltily savor his memories of his few intimate moments with Polly Hunt when movement caught his eye.

His gaze fell on a maid, catnapping, but when he crossed the room to rouse the slacker, he stopped cold, the hairs on the back of his neck and his arms prickling with anticipation.

Her lashes fluttered up just as he knelt to assure himself his eyes were not deceiving him, and then the lady did the most extraordinary thing. She rested a hand on his shoulder, leaned up on her elbow, and gently kissed his cheek.

“Polonaise Hunt, what in God’s name are you doing here?”

He hadn’t meant the question to sound so… panicked, so angry, but she couldn’t be here, could not.

“Hullo to you too, Mr. North,” Polly muttered, her smile fading to a frown. “I fell asleep. Did Beck tell you I was here?”

Gabriel rose lest she kiss him again and scatter his wits from Land’s End to Nova Scotia. “He most assuredly did not, and if he knew this was your destination, I’m going to make him regret his reticence. You must leave.”

“The room?”

“The property.”

She tucked a lock of auburn hair behind her ear, the gesture conveying a significant lack of concern. “I’m hungry.”

“Then take something from the kitchen when you go.”

She treated him to a mulish glance, and Gabriel swiveled to sit beside her before his knees gave out.

“I’m not going.” She rolled her shoulders and yawned delicately. “I have portraits to paint.”

“Go paint them somewhere else.” He was not going to tell her his own house wasn’t a safe place, especially for her, the first woman he could honestly say he’d cared for. More than cared for.

Polly eyed him curiously. “Hesketh has contracted for my services. Who are you to be countermanding a peer of the realm?”

Her hair was tousled, and she had a crease across her cheek from the pillow seam. He crossed his arms to thwart the compulsion to touch her. “I’m Hesketh’s older brother.”

The words were out, blunt, unpretty, and honest, and the effect on Polly was devastating. She didn’t move, she didn’t speak, but she silently withdrew to a faraway, untouchable place, where men could lie to the women they kissed and the women were too smart and tough to let it matter.

“Are you a bastard?” A trickle of hope escaped into her careful tone, and he winced to hear it, because this possibility would explain much and let her forgive nearly as much.

“Not in the manner you mean.”

“I see.”

Silence grew, and Gabriel had the sense Polly was drifting away on an unstoppable tide of hurt feelings and female ire. He wanted to explain, to excuse, to argue on his own behalf in mitigation, but more words would only give her more reasons not to go.

“You really do have to leave, Polonaise.” He said it as gently as he could. “I’m not asking.”

She studied him as she might peruse an anatomical drawing exercise. “Because you are the Marquess of Hesketh, and I am a lowly hired artisan. Your word here is law, and I am banished.”

She rose, not waiting for his reply, and when Gabriel came to his feet, he was reminded how wonderfully her body measured against his. If he took her in his arms, her crown would fit right under his chin. Her expression said he’d never again have that privilege, and though it cut deeply, that was for the best.

“As Marquess of Hesketh, you are bound by the contract that brought me here,” she said, stepping back and gazing across the room at a portrait of two handsome, dark-haired, green-eyed youths. “It is my first commission on English soil, my lord, and it will set the tone for the rest of my career. Aaron and Marjorie Wendover were chosen with care, for their pulchritude and for their social prominence. I will not step back from this assignment, not for any amount of damages, and certainly not because you’ve waved a lordly hand and willed it so. I’ll see you at dinner.”

She turned to go but stopped when he shot out a hand out to encircle her wrist.

“At dinner,” he said, “we will be strangers.”

“Will we?”

“It has to be, Polonaise. For the well-being of all involved, we cannot have met prior to today.”

“Your family might not appreciate your larking away a couple of years in their backyard before assuming the title? Or did you already hold the title when you presented yourself to us at Three Springs as a poor land steward?”

“It’s… complicated, and delicate,” he said, not wanting to give her even that much.

“And you can explain these complications?” Her tone was imperious, but he saw the veiled plea in her brown eyes.

“I cannot. Not now.”

She glanced down at where he still held her wrist. “You can let me go, Gabriel. I’ll not betray your secrets over the fish course. Nor will I leave.”

He did let her go, appreciating the view of her retreat, even as he knew he’d just been poleaxed, blackmailed, and kicked into a ditch in the space of five minutes. This was what he deserved, in the peculiar coincidence of circumstances he found himself.

But then a rare smile lit his features, for he recalled that in those same five minutes he’d also, however fleetingly, been kissed.

Chapter Two

Polly stalked away from His Lordship Gabriel North Wendover Hesketh Whoever He Was, and then rounded on him and marched right back. Afternoon light gilded him from above, as if he were a saintly apparition and not a damnably dear and dark man. She went up on her toes and kissed his mouth this time, a deliberate, angry laying of her lips on his, a battle kiss, without tenderness or artifice.

“That,” she informed him, “is a kiss of parting, as in I’m parting from you, not from your household.”

She whirled off again, feeling better for allowing herself a small display of temper, but by the time she’d gotten to her room, the anger had burned off, leaving hurt and bewilderment.

And shame.

Shame because, of course the Marquess of Hesketh would not have a romantic interest in an itinerant artist, or in the former cook from Three Springs. In his way, Gabriel had been honorable, for he’d refused to enjoy the full measure of the liberties Polly had offered him.

Flung at him, more like.

Just as she’d flung herself at her sister’s husband all those years ago, a stupid girl, flattered by Reynard’s Gallic flirtation and a mature man’s manipulative interest. Dear God, would she never learn discernment when it came to men?

She’d been dreaming of Egyptian treasures on display in the Louvre one moment, opened her eyes in the next, and told herself she was still dreaming. Right before her knelt Gabriel North, whom she hadn’t seen or heard from for weeks, looking concerned and dear, but rested for once. She had kissed him without thinking, without doing anything but giving in to the welling joy of seeing him again, apparition or flesh-and-blood man, and that kiss had been so sweet.

And it hadn’t been a dream, but rather, a nightmare.

For God help her, what of Allie? Polly cringed to think what North—no, Hesketh—would think of a woman who could bear a bastard child, then allow family to step in and raise the child for her. He wouldn’t understand, and he’d be particularly judgmental, because the child was dear to him.

A more reasonable voice told her a man who’d pose for two years as a lowly steward might understand some subterfuge and misdirection, but that voice was drowned out by indignation that Gabriel had never really trusted her, and worry that he could make good on his insistence she abandon her first commission.

Which she would not do.

She’d plead a headache at dinner, write to her sister, Sara, and pray for inspiration to strike. It wasn’t much of a plan, but it would do for now—because it was all she had.

![]()

“Margie!” Aaron called to his wife over the tattoo of her gelding’s hooves, while he took a moment to admire the picture she made. The woman could sit a horse, any horse, and the beasts seemed to wait for her cues and commands. Unwittingly, his mind took off in a spree of lusty associations involving him, naked on his back under her. When he called her name again, it was with greater impatience.

“My lord?” She brought her mount down to the walk, looking elegant, composed, and a trifle flushed. Aaron shifted his gelding alongside hers, and peered at her more closely.

“If I forbid you to visit that miserable old besom who claims to have whelped you,” he asked, “would you cry less?”

“I haven’t been crying.” She drew herself up in her sidesaddle as she emotionally somehow drew herself away. “And you should not refer to your mama-in-law in such terms. For shame.”

“What did she say this time, Margie?”

“She is concerned for her daughter.” Marjorie tossed a glance over her shoulder at her groom.

“Will you walk with me?” Aaron posed the question quietly, because the groom had ears, and Marjorie must have caught the urgency in his tone, because she nodded and waited for Aaron to get down and help her dismount. He handed the reins to the groom and considered how one broached the topic at hand.

First, one waited for the groom to lead the horses away. “We’re married, right?”

“For two years now.” Marjorie regarded him with patient curiosity, while something flickered in her eyes. Something a proper husband would have been able to interpret.

“Is that what her mama-ship was beating you with? There’s no heir on the way, and this must be your fault? If she doesn’t leave you in peace, I swear I’m going to have to do something.”

“She means well.”

“Right, good intentions make every cruelty forgivable.” Aaron silently vowed to have a talk with dear Mama-In-Law. “I’ve some astoundingly good news, Margie.”

She fell in step beside him, and Aaron wanted to take her hand, which was silly really, when Marjorie Wendover would never be so indecorous as to physically flee his presence without being excused.

“Nobody calls me Margie except you.”

Aaron’s lips quirked. “I’m sure if we were honest, there are names only you have applied to my own person.”

She looked puzzled, then caught the humor in his eye. She was young. Not stupid, merely… inexperienced.

“What is your good news, my lord, because you don’t look like a man with good news.” She turned from him as they walked along, pretending to study the undergrowth dying back with winter’s approach.

“Let’s find somewhere to sit, but first tell me, was your mother harping on the need for an heir?”

Marjorie walked along beside him past some purple chrysanthemums. “She was. Again.”

“Do we need to have that argument again as well?”

“No.” She said it quietly, resignedly. “I understand you grieve for your brother, and haranguing you on this topic is not productive. Your decision still hurts me.”

“I know,” he said, wishing this quiet, steady honesty had remained beyond her. “But what I have to tell you should come as a relief in this regard, Margie. It really is good news, at least for us.”

“Us?” She imbued that one syllable with such a wistful longing Aaron felt it in his gut. “Let’s take the bench.” He nodded to a low-backed wooden bench sitting among pots of asters. “We need privacy for this.”

She held her peace, but when she’d arranged the skirts of her habit, Aaron took the place immediately beside her, wishing there was some way to spare her this. He had the strangest urge to tuck her against him, to put his arms around her when she learned she wasn’t the Marchioness of Hesketh, and all her effort over the past two years had been for nothing.

What he ought to feel, what he was entitled to feel, was resentment.

He took her hand. “Gabriel did not die in Spain as we thought. He’s alive and well, and probably at his bath up at the manor.”

Her eyebrows—she had the most perfect eyebrows God ever gave a woman—knitted, as if he’d merely told her rain was likely later in the day. “Your brother, Gabriel, is alive?”

“Very much so. Upright, walking, breathing, and making grouchy remarks to all and sundry. He’s alive, Margie.”

“This is… good news.” She nodded, as if she’d reached for the words blindly and was relieved to have seized the right ones. “This is very good news. I’m happy for you, my lord, and for your… for his lordship.”

“You’re taking this well.” Too well?

“I can hardly fathom it.” Marjorie made to rise, but Aaron kept hold of her hand. “Has he some explanation for allowing us to believe him dead?”

Aaron laced his fingers through hers. “As usual, you ask a good question, Wife.”

“You think I ask good questions?”

“Yes, I do. You use your head, except with your damned idiot mother.”

“Language, my lord.”

They fell silent on that little normalizing exchange, until Marjorie looked down at their joined hands.

“Yes.” Aaron divined the direction of her thoughts. “You might be free of me. Is that what you want?”

“What are you talking about?”

“Margie, you have to realize that with Gabriel reappearing, you have leverage to put this farce of a marriage behind you and snag the prize you’ve waited your entire life to marry.”

She shook her hand free of his grasp. “Your brother is not my idea of a prize, unless he’s much changed.”

“Then what does that make me?”

“You are my husband.” She said this with rare heat, and Aaron had to admit to some relief. She wouldn’t toss him over without a show of loyalty, though he hardly deserved even that much.

“I may not be,” he countered nonetheless, “because you were betrothed to Northbridge, and that was Gabriel, not my humble self.”

“We are married.” Her voice broke on the word, and Aaron did put his arms around her. “Aaron, we are. To the world, we are the Marchioness and Marquess of Hesketh. It’s who we’re expected to be.” She bundled into him, her emotions obviously provoking an uncharacteristic display of… something. Husband and wife didn’t often touch, except for the barest civilities and in public, so Aaron let himself enjoy her fragrant, female curves in his embrace.

God knew, it might be the last time.

“What do you want, Margie?” He propped his chin on her temple and rubbed a slow hand over her back. It was a beautiful back, slender, strong, and graceful, and he’d never really appreciated that before.

“I want to hear what Gabriel has to say for himself,” she said, her words muffled against Aaron’s cravat. “I want some time to put our situation in some kind of order, I want…”

“Yes?” He let her sit up and passed her his handkerchief. “What do you want?”

“This is confusing.” Marjorie blotted her eyes. “Who is the marquess now, when your brother is legally dead? Who votes the seat in the Lords; who has title to the properties? Whose portrait is Miss Hunt to paint?”

Aaron tucked a lock of silky blond hair back over her ear. “That is the least of our worries. I’m more concerned with what we tell your mother.”

“Mama.” The word was a despairing oath. “Oh, God, Mama.”

“Mama and the entire world. You are my wife, for all legal purposes, Marjorie. I’ll not leave you to the vultures, but if Gabriel wants to put things right and have you for his marchioness, you’re going to have to tell me what you want—tell me honestly.”

“You’re saying you’d fight for me?” She smiled, and Aaron wondered why he’d so seldom seen her smile.

But then, he knew why.

“I’m saying, I’m your husband,” he reiterated, “and I will act in that capacity until you tell me you’d rather I didn’t.”

Marjorie sat a little straighter, and damn him, because he missed the feel of her in his arms. “We don’t know what Gabriel intends, your lordship. This whole discussion might be moot. He could have married some Spanish beauty and be waiting to shock us with that surprise as well. Where was he for two years while we were getting married and mourning and trying to get Hesketh set to rights?”

“I honestly haven’t asked him that, though in truth, Margie, I don’t think Gabriel will be your most challenging issue.”

She folded his handkerchief in her lap so the lace edges matched exactly. “If Gabriel intends to have me for some kind of wife, his wishes will carry great weight in the courts, won’t they? He’s used to getting what and whom he wants.”

Aaron drew her to her feet. “Maybe he was, but he seems different. Every bit as irascible, but not as arrogant.”

“That should be the subject of a notice in the Times,” Marjorie said, tucking her arm around Aaron’s. “Not that he’s miraculously restored to us, for Lazarus at least set a precedent in that regard, but that he might have learned some humility.”

“Now, now.” Aaron jostled her affectionately. “People will be saying you’re your mother’s daughter.”

“And your wife. At least for the present.”

![]()

“So there you are.” George rose, his hand extended toward Gabriel as he welcomed him into the cozy manor house that served as the steward’s quarters. “In the flesh, just as your note said.”

His handshake was solid, welcoming, and in two years, George had barely changed. He was aging well, typical of the Wendover men. He wasn’t quite as tall as Gabriel or Aaron, but he was quietly handsome, with brown eyes instead of green, and a patient humor with the things that set younger men to cursing and stomping around.

“It’s good to be home, George,” Gabriel mouthed the platitude as they took their seats in the library, though it was the truth, too. “How fare you?”

George lapsed into the predictable soothing patter of a man stewarding a huge agricultural enterprise. The estate held dozens of tenant farms, spread over tens of thousands of acres, and after twenty years in his position, George knew every acre of the property. Gabriel let his cousin roll on, about this pond silting up, that field needing to fallow, and the other tenant having yet another strapping daughter.

“You might try barley straw in the pond,” Gabriel suggested, “if the problem is scum as well as silt.”

George’s eyebrows rose. “Barley straw, you say? Is that something you picked up in Spain?”

“I did.” Gabriel lied easily, though this was one of Beck Haddonfield’s tricks. As much as Beck had traveled, he might have picked up the notion in Spain. Or the Americas, or the Antipodes.

“Were you so long ill, then, that you couldn’t come back to us for two years?”

“It’s a long story, George, best told over a long winter night with a decent bottle or two at hand. Why are you emptying one of the hay mows?”

“Mold.” George spat the word, as only a farmer facing winter would. “Damned rain or some such. Hay goes bad, but this was a damned pretty crop. We’re fortunate not much was damaged.”

“Is the roof leaking?”

“Mayhap. We’ve had some bad storms this fall, and rain can get in under the eaves when the wind blows just right. I tried to suggest to his lordship, your brother, we might be caulking the eaves, but he says the hay needs to breathe. Has a lot of answers, that one.”

“You educated me when I thought I had all the answers.”

“That I did.” George produced an unlit pipe from his pocket. “Or tried to. So who has the title now, Gabriel? And which title?”

What did that matter when hay was getting wet? “One of us is Hesketh, the other is a courtesy lord. I care not which is which, but the solicitors, judges, and the College of Arms will likely have an opinion. In either case, the land needs tending, and you’re the man to do it.”

“You might want to see if your brother agrees. He’s full of notions and has us marching off in this direction, only to charge off another day in that direction.”

“Which sounds just like him.” Gabriel watched as George went through a familiar ritual of cleaning, filling, and lighting his pipe. “I trust you to interpret his orders accordingly, but until we sort out the legalities, you will continue to honor his directives.”

“While the hay molds,” George muttered. “I’ll do as you say. Harvest is in, and the sheep are getting fat and woolly. The stock is in good shape for winter, and most of the cottages are in good repair. There shouldn’t be all that much to do, in truth, not until spring.”

“When there’s too much to do. Will you join us for dinner some night this week?”

“Of course.” George winked. “You need all the reinforcements you can get, and I’ve got your back.”

“I’m grateful for that.” Gabriel rose and offered his hand. “All the time I was gone, George, I worried a little less because I knew you were here, and you’d prevent the worst disasters and clean up after the ones that couldn’t be avoided.”

“A steward’s job in a nutshell.” George grinned, then became more sober. “You’re going to have to let the world know what you were about, though, Gabriel, gone for two years without so much as a letter.”

“Had I been able to communicate, I would have, and likely with you. My man of business in Town knew what was afoot at all times, but things grew complicated.”

George shot a look in the direction of the manor house. “With you lot, they usually do. Me, I tend the sheep, and life is not complicated at all. You work, and then you work some more, and then you work yet still more, with eating and sleeping tucked in somewhere between sheep, goats, cows, horses, crops, and cottages.”

“It’s not a bad life, though, is it, George?”

“For some it’s not. For others, well… Let’s just say I’m not sure you or your brother would find being a steward entirely agreeable.”

Gabriel took his leave on that note, but wondered what George would think did he know that for two years, Gabriel had been the one to tend the sheep, the cows, the crops, and so forth.

And he’d never been happier.

![]()

Gabriel’s reunion with his former fiancée had been an awkward, uncomfortable moment when they’d gathered in the family parlor before the evening meal. She’d curtsied, he’d bowed, and then he’d taken a step toward her, only to see her cringe and back closer to Aaron. Gabriel had followed through nonetheless, and offered her a careful, fraternal hug, even as he wondered how this tall, slender girl—no, woman—was managing the burden of being the Hesketh marchioness.

And she was a woman, a pretty, though very young woman upon whom Gabriel had made duty calls between terms at school. He’d ridden out with her in pleasant weather on holidays—properly chaperoned, of course—and danced her first waltz with her. She’d been a quiet, inevitable presence in the back of his mind, and as she’d reached adulthood, her calm blue eyes had asked if he were going to set a date.

He hadn’t, being far too enamored with the pleasures of being an heir, then gradually, as his father had aged, with the burdens thereof. And through all this, when they might have become friends, they’d remained strangers—awkward, proper strangers.

How had he let that happen?

“Welcome home.” Marjorie’s smile seemed genuine, if shy, and Gabriel tried a smile in response.

“It’s more wonderful to be home than you can imagine, my lady. I must compliment you on the house, for I’ve never seen it looking better.”

“Are your rooms comfortable?”

The polite question of a conscientious hostess caused her to blush, and Gabriel saw endless evenings like this, conversation stilted, more unsaid than said.

And that was his fault too.

“They are exactly as I’d wish,” he replied, and the response caused Aaron’s eyebrows to twitch with what looked like consternation. “My surrounds have been humble the past two years, and I’ve developed a taste for simpler living. The day starts more easily when one doesn’t have to await a valet to dress, a maid to dine, and a groom to fetch one’s horse.”

“And you’ll enlighten us about those two years?” Aaron posed the question, taking his wife’s arm—protectively?—as he did.

Marjorie spoke up. “My lord, can I not enjoy your brother’s company for a single meal before you men must talk of serious things? I noted his lordship is riding a splendid fellow of mature years with a story emblazoned on his quarters.”

Aaron slid his arm around Marjorie’s waist, his expression bemused. “The girl is horse mad. One of her many fine qualities.”

Another blush, but softer, and directed at Aaron by his own wife. Gabriel was reassured by the exchange, because surely a woman didn’t blush at a husband she resented?

“Soldier was at the knacker’s when I found him,” Gabriel said, “stoically awaiting his fate with a great gash on his backside from one too many skirmishes with the French or the local bandits or heaven knows whom. He was all I could afford, but he has excellent conformation, and all the sense and bottom of a seasoned campaigner, provided I make allowances for his injury.”

“He looks like he’d be a keen jumper,” Marjorie said, and the topic of horses and the current population in the Hesketh stables served to get them through dinner. Marjorie excused herself thereafter, leaving the gentlemen to their drinks.

“Shall we remove to the library, so the kitchen can clean up?” Aaron suggested.

“We shall.” Gabriel rose and moved across the hall with his brother. “And so these old bones can rest by a roaring fire, because the night is getting damned chilly.”

“Your back bothers you when it’s cold?” The question was posed casually, because even a brother trod lightly in certain areas, and Aaron was careful to be busy poking up the fire as he spoke.

“My back bothers me constantly,” Gabriel admitted. “I’m like my horse. I manage well enough, but if I overdo, I pay dearly. And sometimes, when I don’t overdo, I pay just as dearly.”

“Laudanum?”

“Not on a bet.”

“This might help.” Aaron passed him a glass of brandy. “These past two years, you were close by?”

“For most of it.”

“You came by, didn’t you?” Aaron poured his own drink and studied the decanter upon which, Gabriel knew, he would see the Hesketh wheat sheaves etched—the heraldic symbol for hopes realized. “At times, I felt as if you were watching, but I’d turn around, and no Gabriel. Gabriel was dead. I was almost sure of it.”

Gabriel said nothing, because admitting he’d spied on his brother wasn’t going to help their situation.

“I know what you’re about, Gabriel.” Aaron set the decanter aside. “You’ve been trying to make up your mind whether I tried to have you killed. And you couldn’t come to a conclusion from a safe distance, so you’re bearding the lion, so to speak.”

Gabriel lowered himself into a well-padded chair—though the seat still wasn’t as comfortable as his chair in Polly Hunt’s kitchen. “If I ask the question directly, you’ll have to call me out.”

“Suppose I will.” Aaron took the other chair while Gabriel envied him his ease of movement. “You’re suffering more than a twinge in your back now, aren’t you?”

“Not really. It knocks me on my arse from time to time, but mostly it’s stiff without being painful. I meant it when I said the place is prospering. You’ve done well, Aaron.”

“I’m not sure if I should resent that comment, or appreciate it, coming from you. I’ve made some changes, but it’s all right there in the estate log.”

“What’s the estate log?” Gabriel didn’t make the effort to rise. The day had been long, the ride down from Town grueling, and the estate book wasn’t going anywhere.

“I’ve found dear George doesn’t have perfect recall,” Aaron said. “He isn’t one for noting exactly which herd dropped the first lambs, or which farm the scours started on, and so forth, so I started keeping a log. It’s useful.”

“Useful?” The heat from the fire was the most useful thing Gabriel had encountered since finding Polonaise Hunt lurking in his portrait gallery.

Aaron’s portrait gallery.

“George was going to let three hundred acres fallow three years in a row,” Aaron said. “We damned near came to blows about it. He was sure it had been planted the year before. I showed him the harvest entries, but even then, he tried to tell me I’d forgotten to enter three hundred acres of yield, rather than admit he’d forgotten the land had sat idle. The tenant didn’t want to get into the middle of the argument, but eventually his was the deciding vote.”

“Stewarding is a much more difficult and interesting job than I’d thought. Exhausting, too.”

“Is that what you were doing? Serving as somebody’s land steward?”

“Yes.” When he wasn’t falling in love.

“I’ll bet that was an adjustment.”

The comment was neutral, not angry, not resentful, not even jeering, but Gabriel wasn’t sure what to say in response.

Aaron rose and set his glass on the mantel. “I know you’re still trying to make up your mind. Am I your brother or your enemy or both? You’ve been through an ordeal, and though I ought to treat you to some of the home brewed for thinking as you have about me, you’ve had your reasons. Still, your reappearance has cast a great deal into confusion, and for Marjorie’s sake more than my own, we need to know what you’re about.”

“What I’m about?”

“She was your fiancée, not mine. I married her for reasons you may discuss with her, but I’m wondering if the marriage is valid, given that it was effected under false pretenses.”

In all his wildest imaginings—and some of them had been wild indeed—Gabriel had not envisaged that Aaron’s marriage would become a bone of contention. “You’re accusing me of fraud, when I lay on my stomach for months—?”

Aaron held up a hand. “Part of the reason I find myself with your wife, so to speak, is because Lady Hartle started rallying her solicitors for a breach of promise suit. Her daughter was to be the Marchioness of Hesketh. Your arrival means some other lady will hold that title.”

“Unless I never marry.” He’d been almost resigned to such a fate, in fact.

“I won’t ask that of you, because it would put the burden of the succession on my humble shoulders, exactly where it is now. Moreover, it won’t spike Lady Hartle’s guns if you remain a bachelor. The simply fact that you’re alive takes the title from Marjorie and me.”

“Blessed Infant Jesus.”

“Marjorie asked me, when I told her you lived, who votes your seat when you’re legally dead. Who directs the solicitors? To whom do the Hesketh holdings belong? Whose portrait is Miss Hunt going to paint?”

“Your artist.” The artist who’d dodged dinner in a show of either pique or great good sense. “That one is easy. Send the lady packing, given the confusion you allude to.”

Aaron picked up his glass from where he’d set it on the mantel, and appeared to study the contents. “And thereby notify the entire polite world you kept your existence secret from your own brother for two years, that you made a joke of the Lords, or you’ve gone half lunatic on us, seeing plots where they don’t exist?”

“I take your point.” Gabriel felt weariness pressing down on him. Getting Polly the devil away from Hesketh had become his most immediate concern among many immediate concerns. “She can start with a portrait of Marjorie. That should be safe enough if we keep the footmen close at hand and insist on an indoor sitting. Your wife is very pretty, by the way.”

“Ah, but is she my wife?”

“Do you want her to be?”

“It matters naught what I want. The resolution of Marjorie’s status will lie with what she wants, and let me be clear on this, Brother. As far as I’m concerned, it matters not what you want, either, not one bit, not to me.”

“That’s as it should be.” Gabriel tossed back brandy that should have been sipped and set his empty glass aside. “But I’m loathe to suggest I could be marrying her.”

“Why?” Aaron regarded him steadily. “If she’s used goods, it’s not her fault.”

“Used… Aaron, don’t be vulgar. I’d hardly hold it against Marjorie that she did her duty by her lawful husband as she knew him to be, though it would be decidedly awkward. I get the impression she’s fond of you.”

Aaron’s fingers tightened on his glass. “She’s too decent to give any other impression, but we’re not close. That would hardly be fashionable.”

“Hang fashion. My hesitance stems not only from reluctance to displease the lady, but also from a desire not to see her dragged into whatever ill will has been directed to me.”

The last swallow of Aaron’s drink disappeared. “You are absolutely convinced somebody tried to kill you?”

“Repeatedly,” Gabriel said. “Even as I prepared to take ship from Spain, I was set upon on the docks, twice. Both times, my attackers knew my back was weak. Were it not for the Spanish sailor’s inherent championing of the underdog, I’d be gone in truth.”

“And you were supposedly dead by then,” Aaron murmured. “A tragic victim of the convent fire.”

Gabriel stared at the crackling blaze his brother had obligingly built up for him. At this rate the reading balcony immediately above would be a cozy place to hide, except stairs lay between it and Gabriel’s present location. “All of which means I am still a target.”

“Unless your detractor was content to have you out of Spain, but who in that country could wish you ill?”

“And who even knew I was there, except my family?”

“Complicated,” Aaron agreed. “The sooner you make your intentions known in terms of the legalities and practicalities, the sooner Marjorie can get on with her life, or her mother with a scandalous lawsuit.”

“There will be no lawsuit.”

“You’ll marry Marjorie then, if Lady Hartle insists?”

“I can’t promise that. Make sure Marjorie knows I can’t promise to wed her.”

“You make sure she knows,” Aaron said as he headed for the door. “It should be an interesting conversation, and I’m sure one of you will let me know how it goes.”

“Good night, then.” Gabriel was too tired to heed the requirement of manners and rise. “You won’t mind if I have a look at that estate book?”

Aaron waved a hand. “Do your worst, and please God, don’t neglect the ledgers. For my part, I really am glad you’re back, Gabriel. The less time I have to spend with the paperwork, the correspondence, and the damned bills, the better. You argue with George, and meet with Kettering, and dance the damned pretty at all the mandatory social events.”

“While you do what?”

“Admire my brother.” Aaron bowed, and came up smiling not quite innocently. “One other thing, Gabriel?”

“Hmm?”

“The girl, Melinda? She’s thriving.”

“I know.” Two words, but even keeping that much steady had been effort. “Kettering told you?”

“Your will has that codicil, and he had to show it to me because I’m your executor, nominally, and then too, I think Kettering has a care for children.”

“He does. My thanks. I’ve kept an eye on her as best I could, but that hardly served.”

“Thought you’d want to know.”

Gabriel let him go, knowing Aaron hadn’t owed him that last exchange and hadn’t owed the child anything. And this was the brother Gabriel had been convinced was intent on fratricide. Increasingly, that notion seemed ludicrous.

Chapter Three

Taking dinner on a tray was not an act of cowardice. Polly assured herself of this as she studied yet another botched sketch of a certain breeding sow who had been dear to the land steward at Three Springs—the former steward. To allow the Wendover family to dine in privacy the first time they sat down together since North’s return was courtesy.

Not North. He was Hesketh, the marquess himself. Had been, the whole time he’d been feeding slops to Hildegard and wrestling sheep from the pond muck at Three Springs.

Polly tore off the sketch of Hildy—the pig’s expression had been uncharacteristically downcast—and instead drew a careful, aquiline curve near the middle of the page. The curve grew into Gabriel’s nose, then his mouth, and his beautiful, serious eyes.

Not Gabriel, not North. Hesketh. Lord Hesketh.

The entire time he’d been permitting Polly the occasional liberty—a kiss, an embrace, a cuddle—he’d been Hesketh.

With a huff of self-disgust, Polly set her sketchbook aside. The Wendover family Bible would be in the library. Knowing Gabriel’s antecedents would appease the curiosity she had about him—had always had about him.

From the first time he’d showed up at her kitchen door—tall, gaunt, and bearing a letter from Lady Warne—Polly had been interested in Gabriel North.

Gabriel Wendover, she corrected herself, finding a flannel wrapper and belting it tightly. The corridors were lit by only the occasional sconce, but it was enough, because the moon was full and Polly knew her way.

Someday I am going to have my own house. Nothing so grand as this, but something as light and elegant and comfortable. I’ll have a library and a studio, and my family will be welcome.

My daughter will be welcome.

She opened the library door, a comforting warmth enveloping her as she stepped into the room.

And stopped.

Somebody had pushed the long sofa right up close to the hearth, using it as a sort of fire screen, though the spark catcher was still in place as well. Moving silently, Polly stepped closer, peering over the back of the sofa.

Gabriel was stretched out on his stomach, a fat ledger open for his perusal.

“Brandy is on the sideboard, if that’s what you’re looking for.”

He didn’t glance up, but Polly knew he could identify her scent—he’d confessed as much once on a dark, lovely night.

“Would you like some?”

“I’ve already indulged, but help yourself.” He stirred, setting the book aside and shifting to sit.

“Your back is hurting?”

“Of course. You’re having trouble sleeping?”

“Of course.”

“Come sit, then, Polonaise, and you can tell me how our dear Allemande fares.”

He would ask that, damn him.

She helped herself to brandy and poured him a glass despite his demurral. By the time she’d brought both to the sofa, he’d pushed the furniture back to a more usual distance from the fire.

“Should you be shoving furniture around if your back hurts?”

“Should you be offering brandy to me when you’re in such fetching dishabille?”

“Don’t be churlish.” She handed him his drink and sat a small distance from him. He rose and tossed a log on the fire, while Polly watched his movements. She’d seen him move much more slowly, and manage in surrounds far less commodious than this.

“Allie is well enough,” Polly said. “She’s angry at me for leaving Three Springs, but Beck and Sara are patient with her, and her Uncle Tremaine is a nice distraction.”

“The Sheep Count. His nom de guerre among the merchants. Every girl can use a wealthy uncle.”

“He doesn’t use the title.” They fell silent, but when he resumed his seat, Gabriel settled right beside her, hip to hip, as he often had at Three Springs. When he’d first developed the habit, she thought he’d done it as a simple, animal way to garner some human warmth for himself, but when he’d taken no more advantage than that over weeks and weeks of opportunity, she’d realized he was doing it for her, to alleviate her loneliness in the small ways that wouldn’t cause talk or stir feelings.

And she’d been grateful.

She was still grateful, which would not do.

“So tell me why you did it, Polonaise.” His voice was the same rasping baritone she’d heard many times before, but here before the fire, it carried a kind of fatigue she’d not sensed previously.

He wanted to send her away, and they might not cross paths again. The thought inspired honesty, of a sort, and sadness.

“Why I did what?”

“Why did you leave your family at Three Springs to make wealthy, spoiled people look pretty for all eternity?”

“Why did you leave?” Polly had never been intimidated by him, not by his size, his intellect, his brooding silences, or his irascible demeanor. “You told Allie your family was in trouble, but this”—she waved a hand—“looks as untroubled as can be.”

“I lied.”

“You don’t lie.” She took a sip of very smooth spirits, such as a true lady would not admit she drank. “Well, perhaps you do.”

“Not willingly or often,” he countered. “I don’t care for it.”

She glanced at the saturnine planes of his face as the firelight cast them in flickering shadows. He did not care for himself when he dissembled.

“Which was the truth, then? That you desired me, or you were only humoring my… attraction to you?”

He helped himself to a sip of her drink though she’d brought him one of his own. “Polonaise, will you never learn a little indirection? The day has been long and fraught, and either answer leaves me looking like a bounder.”

“So which bounder will you be?” She sipped her drink from the exact same place on the glass he had, and let the brandy burn down to her center before going on. “Will you be the man who didn’t want to tell me my importuning was pathetic to one of his stature, or the man who took small liberties for the sheer hell of it, without thought to the consequences?”

“Not pathetic,” he ground out. “You’ve gotten your nightcap. Hadn’t you best be off to bed?”

She tidied her skirts as if to rise, but rather than heed him, she scooted her feet up under herself on the sofa.

“I’d like an answer,” she said. “Any answer, Gabriel, because you owe me that much. I don’t have to like it, but if it’s the truth, I’ll live with it. You mean to send me away, after all, so grant me this boon: What were you doing with me, Gabriel? Why mess about with the lowly cook when you could have entertained yourself in any style you chose in Town?”

“You’re not asking what I was doing at Three Springs in the general case, I note.”

“That is your business. I’m not going up those stairs until you tell me what you were doing with me, in the specific case.” She had no way of enforcing her threat. Sore back or not, he could easily toss her over his shoulder and eject her from the room bodily.

And she would like to see him try, because it would give her an excuse to be in some form of his embrace.

“I’m not sending you off immediately,” he replied, and they both knew he was dodging her question yet again. “Aaron wants Marjorie’s portrait done now, and I will respect his wishes, but there are rules.”

Polly took another sip. “With you as the Marquess of Hesketh, one expects rules regarding a great deal.”

“You will pose her indoors, and there will be footmen in attendance,” Gabriel said. “You will keep me or Aaron informed of your whereabouts at all times, and when Marjorie’s portrait is done, you depart without a word of the goings on here.”

She gave him a peevish look for the insult implied at that last condition.

“Whatever is going on here, the news has already reached every estate within a five-mile radius, Gabriel.”

“You don’t need to add fuel to the flames of gossip. For your own safety, you do not.”

“Is that a threat?”

“Jesus save me.” He hunched forward and scrubbed a hand over his face. “You’d call me out were it intended as such.”

“And my weapon of choice would be the muffin pan,” Polly replied. This provoked a tired smile from the man beside her, and she let herself smile back. “Gabriel, I really would like to hear that you weren’t trifling with me. A woman feels foolish when the first man she’s taken an interest in for years turns out to be so far above her touch.”