Trenton

Lord of Loss

Book 10 in the Lonely Lords series

After a short, troubled marriage Trenton Lindsey, heir to the Wilton earldom, finds himself a widower with three small children. His year of mourning leaves him adrift, until his brother Darius forces him to take a repairing lease in Surrey. Social conventions require Trent to call on his recently widowed neighbor, Elegy Hampton, Lady Rammel, and as friendship develops, consolation of an intimate sort tempts them both. Just as Trent acknowledges the joy and pleasure to be shared with Ellie, an unseen enemy threatens him and Ellie, too. Can he reach for the love Ellie offers, when some one else is trying to take his life?

Bonus Materials →

Enjoy An Excerpt

Chapter One

“How long before the baby moves?” As Elegy Hampton, Viscountess Rammel, put that question into words, her world became more a wonderful place—also more frightening.

She poured her guest another cold glass of lemonade but left her own drink untouched. Something as prosaic as a glass of lemonade did not belong in the same moment with Ellie’s question.

“A few weeks yet at least, closer to a few months probably,” Mrs. Holmes replied. “You’re not that far along, my dear, and every case is different.”

I am with child. The drowsiness, the delicate appetite—even the lemonade tasting a bit off—the sense of Ellie’s body being out of balance was not grief, but, rather, the very opposite of grief.

“Nine months seems like forever,” Ellie said. “I suppose it could be worse.” Horses took eleven months, poor things.

“Nine and a half months for most.” Mrs. Holmes’s expression was beatific, a serene complement to snow-white hair and periwinkle-blue eyes. “That last half-month can seem as long as the first nine. Perhaps it’s the Lord’s way of ensuring mothers start off schooled to patience.”

Oh, please, let’s not bring Him into the discussion. Ellie and the Lord had not enjoyed cordial relations of late. Though having a baby…

She wanted to cry and laugh. Oh, Dane. Thank you, damn you. Thank you.

“Patience has never been one of my strong suits,” Ellie allowed. Since her husband’s death, the very air had acquired an unhappy weight, making movement, breath, thought, everything a greater effort and solitude a particular torment.

Yet now, Ellie was impatient to have the sunny, serene morning room to herself.

“You’ll manage,” Mrs. Holmes assured her. “But Miss Ellie? You’ll forgive my bluntness if I suggest you occupy yourself with cheerful endeavors. Mourning must be given its due, but excessive fretting isn’t good for the baby.”

“Fretting?” Ellie had done nothing but fret since Dane’s death.

“I will help you bring this baby into the world, and a certain directness of speech should characterize our dealings,” Mrs. Holmes went on, though Dottie Holmes had never needed excuses for direct speech. “His lordship was a fine young man, and he should be mourned by his family, but you’re young, you were a good wife, and you’ve much of your life ahead of you.”

“I do mourn him,” Ellie said, hoping it was true, though the words had the same off flavor as the too-sweet, too-tart lemonade.

“Of course you do.” Mrs. Holmes patted Ellie’s hand with fingers made cool by the chilled glass. “Nobody doubts you were devoted to him, and now you must devote yourself to the child. His lordship has been gone nearly two months, and when you are here at home, you might consider putting off your blacks, going for the occasional easy hack around the property, and enjoying the condolence calls when they start up in earnest.”

How was she supposed to enjoy condolence calls, when the pleasure of even a glass of lemonade was in jeopardy? Ellie hadn’t been able to venture to the stables for nearly a month after Dane’s death, and she loved the very scent of the horse barn.

“You want me to ride when I’m carrying?”

“As long as your habits fit. Don’t take stupid risks, Miss Ellie, and stay active. You’ll carry better if you get fresh air, keep moving, and indulge yourself a bit.”

Dane had excelled at getting fresh air, staying in constant motion, and indulging himself—more than a bit.

“I hate black,” Ellie murmured, running her thumb down the side of her glass.

A lady ought not to hate anything, and the conduct of widows was supposed to put them only slightly lower than the angels.

Sad, angry angels.

“Black doesn’t flatter much of anybody,” Mrs. Holmes agreed, helping herself to a slice of lemon cake that, to Ellie, also had no appeal whatsoever. “Clearly, black for mourning was devised by men, who are much more at home in dark and forbidding colors. Have something to eat, dear, so I won’t be self-conscious about seconds myself.”

Thirds, at least.

“Of course.” Ellie put a slice of cake on her plate. I am having a baby. I am having a baby. I am having a…baby. Women died in childbirth all the time. “I’m to take exercise and sneak into half-mourning, and what else?”

“Your digestion may act up from time to time.” Mrs. Holmes nibbled her sweet complacently. “Your breasts might be sore. You’ve no doubt noticed a tendency to nap and heed nature’s call more frequently. That’s all normal. You’ll be losing your waist soon, if you haven’t noticed your dresses fitting more snugly already—your boots and slippers, too. Some lightheadedness isn’t unusual, but it passes.”

“I’ll go barefoot,” Ellie said, her hand going to her middle. Dane would have been horrified to hear her. In his way, he’d been a proper old thing—with her. “I went barefoot a great deal in summer as a child.”

“And you’ll have a child to love.” Mrs. Holmes beamed confidently. “A reminder of his lordship and the happiness of your marriage.”

Ellie already had a child to love, and what happiness she’d found in her marriage was of the tempered variety. Still, she hadn’t been entirely miserable, and Dane should not have fallen from his horse at the age of twenty-eight. He was—had been—a bruising rider.

When sober. He’d claimed he rode even better when drunk—and he’d been wrong. Ellie regretted his death, but even before his passing, she’d reconciled herself to missing him and missing what their marriage might have been.

She was having a baby, and above all else, Ellie wanted solitude to savor this realization. “Another glass of lemonade, Mrs. Holmes?”

“Not for me, my dear, but drink as much as you please, particularly in this heat.”

“I like summer.” Ellie especially enjoyed feeling wet grass between her toes first thing in the morning and leaving her windows open to let in the bird song. “I like the lighter clothing, the long days, and the soft breezes. I like the sturdy young beasts finding their confidence in the mild weather. The nights are rife with the scent of the flowers and fields, and the mornings are lovely.”

“You’re an expectant mother,” Mrs. Holmes replied around a mouthful of cake. “You should be in love with life.”

When had Ellie ever been in love with anything, or anybody? She rose, in part to get away from that question, but also to suggest—politely, of course—that the call should come to an end. “I’m a widow, too. Like you.”

“Some sixteen years now.” Mrs. Holmes touched her throat, where a lock of sandy hair had been cross-woven in an onyx mourning brooch. “Widowhood gets easier with time, Miss Ellie.”

“Does it?” Marriage certainly hadn’t become any easier with time. Ellie went to a window overlooking a back terrace in riot with potted pansies. Mourning was difficult for several reasons, unrelenting loneliness only part of it. A steady flame of anger illuminated Ellie’s days and nights, as did a rising tide of bewilderment. “Do the nights get easier?”

“Ah. This is difficult, because you are with child and young.”

“A pair of blessings, supposedly,” Ellie muttered, crossing her arms. One was supposed to keep such comments to oneself.

“The preachers would have us believe childbearing is a blessing, but the loneliness known to widows isn’t often under discussion in the pulpits on Sunday morning.”

Such loneliness was never under discussion on Sunday mornings. Ellie’s pastor had, of course, called upon her following the funeral. He’d dropped back to monthly calls now, the same schedule he’d been on before Dane’s death.

Ellie wasn’t about to discuss her nights with old Vicar Hughes.

“How do you cope?” Ellie asked, dropping her forehead to the window glass. Why hadn’t anybody opened the window when outside the day was so pleasant? “How do you reconcile yourself to years and decades of being alone? Dane and I weren’t especially close, but he was a husband. He was there, however infrequently.”

Though when he’d been home, Ellie had always felt some awkwardness, some sense that she wasn’t passionate enough, desirable enough, or maybe not feminine enough to meet his expectations.

They hadn’t talked about it. They’d talked about little, in fact.

The marriage bed had been mostly duty, but Dane had also dispensed a kind of casual, bluff affection when he’d been at Deerhaven, and Ellie missed his touch more than she could sometimes bear.

“You stay busy,” Mrs. Holmes said, “and you use discretion.”

Ellie whirled at that suggestion, but Mrs. Holmes was still placidly sipping her lemonade and nibbling her cake, the picture of grandmotherly complacency.

“You are scandalized,” Mrs. Holmes said, “which does you credit, but, my dear, would his lordship have been celibate while he grieved your passing?”

That didn’t deserve an answer, for nothing had come between Dane Eustace Hampton, Viscount Rammel, and his pleasures. Ellie paid the household bills and knew good and well that few of the fine snuff boxes, quizzing glasses, and rings Dane had purchased in five years of marriage were in her possession—or his.

Then too, Dane’s nickname hadn’t been Ram for nothing.

“How Dane would have consoled himself is of no moment. Gentlemen and ladies are held to different standards,” Ellie said.

“Widows are a different breed of lady. We are considered safe by the menfolk, because we’re experienced, discreet, grateful, and financially independent. You’ll find the mature bachelors in the neighborhood singularly attentive to your grief.”

Ellie was carrying a baby, and this conversation was not relevant to…anything. Though those attentive, mature bachelors might explain why Dottie Holmes enjoyed such unfailing good cheer.

“I’m breeding, Mrs. Holmes. What man would find that attractive?”

Mrs. Holmes gave an ungrandmotherly snort as she buttered a cinnamon-dusted scone. “Most of them. They can’t get you with child, can they?”

Cinnamon held inordinate appeal of a sudden, though the idea of bachelors leering at Ellie’s bodice…damn you, Dane. “But my condition isn’t common knowledge. I wasn’t sure myself until you told me just now.”

And if Ellie hadn’t missed her courses—she never missed her courses—the notion still would not have occurred to her.

Mrs. Holmes added an extra dab of butter to her scone. “You attributed odd symptoms to grieving, which does take a toll, of course, but you are most definitely in anticipation of a blessed event. I’m merely suggesting these early days are an excellent time to find solace in the arms of a discreet gentleman or two.”

Merciful Halifax. “Or two?”

“You need only be discreet.” Mrs. Holmes popped a bite of scone into her mouth while Ellie digested this very odd advice.

“Think of it this way, Miss Ellie: By leaving you with a baby to love and care for, his lordship also left you with a way to find some comfort without suffering consequences. Decent of him, one could say.”

“Shame on you, Dottie Holmes.” But Ellie hadn’t the knack of starchy propriety, and Mrs. Holmes was smiling as Ellie escorted her down the front terrace steps a few minutes later. “I do thank you for coming.”

“I’ll be back next month.” Mrs. Holmes pulled on her driving gloves as briskly as any four-in-hand coachy. “You must send for me if you have any distressing symptoms.”

“You’ll keep this to yourself?”

A blue-eyed gaze flicked over Ellie’s middle meaningfully. “Of course, though soon enough, the situation will be evident, my dear.” She climbed into her pony cart, clucked to the shaggy beast in the traces, and tooled off down the drive.

Leaving Ellie’s world forever changed.

“Is that the baby lady?” Eight-year-old Coriander came skipping down the steps, her eyes bright with interest—and her pinafore still clean, thank heavens.

Ellie held out a hand to her step-daughter. “She’s the midwife. She’s known me since I was your age. Were you eavesdropping?”

“Hiding,” Andy replied, taking Ellie’s hand and leading her back into the house. What did it say that the child must lead the adult indoors? For Ellie would have remained staring down that drive until nightfall.

As if she were expecting Dane to come cantering home, so she could tell him this happy news?

“You would have made me sit with my ankles crossed, back straight, and only one scone to console me,” Andy accused—accurately.

The child had her father’s blond good looks and his charm, which was fortunate. “I’d inflict such a dire fate on you and starch your pinafore until it crackled when you moved.”

Andy sniffed at a bowl of roses wilting on the sideboard, though even from a distance, Ellie could tell the scent would no longer be pleasant.

“You’re supposed to teach me manners, Mama.”

“You’re clearly in command of them, but, like me, you prefer theory to practice.” Also going without her shoes. “Speaking of practicing, what are you doing out of the schoolroom, young lady? Luncheon hasn’t even been served yet.”

“Mrs. Drawbaugh sent me down to ask if we might picnic for supper. She says the weather is fine and time out of doors makes me behave better.”

“She didn’t say that.” Minty and Andy had quietly decided time out of doors would do Ellie some good. The conspiracy of the schoolroom had grown only closer in recent weeks.

Andy grinned like the little girl she was. “I said it, and it’s as true for me as it is for you, so please say yes. Mrs. Drawbaugh likes to be outside, too.”

“Don’t bat those eyes at me, Coriander Eustace Brown,” Ellie remonstrated with mock severity. “The answer is yes, provided your schoolwork is done. If you dawdle on your exercises, Minty and I will enjoy nature without your company, while you have porridge in the nursery.”

“Not porridge!” Andy lapsed into melodramatic gagging. “Never say it! Poisoned by porridge!”

Ellie cut her off with a gentle swat on the backside and a hug. “Upstairs, and get your work done. I’ll expect a favorable report at supper.”

“Yes, Mama.” Andy paused just out of swatting and hugging range. “Why was the baby lady here?”

“She was paying a condolence call. People will start to do that, particularly when your papa has been gone three months.”

“I’m not as sad now. Why offer condolences three months later and not when Papa died?”

Because no matter when they were offered, the condolences did nothing to make the departed any less dead. Waiting three months gave a widow some time to adjust to that reality.

“Blessed if I know, but you’re stalling. Be off with you.”

Andy scampered up the steps two at a time, leaving Ellie to wonder why she’d lied to the girl about the baby, when honesty was something Ellie and Andy both valued very much.

* * *

“Rest, eat regularly, mind the drinking, and don’t forget to write.”

Darius Lindsey sounded more like a stern papa than a younger brother as he delivered his parting admonitions. He hugged Trent once, then swung up on a piebald gelding and cantered off into the building heat of the summer morning.

Trenton Lindsey—more properly, Viscount Amherst—stood outside the Crossbridge stables, already missing his brother and mentally searching for ways to put off, of all things, a damned condolence call.

“If I wait until later in the day, it will be even hotter, and I’ll be forced to swill tepid tea, while some puffy-eyed matron clutches her hanky and tries bravely to make small talk.”

Arthur’s gaze suggested commiseration, for he’d be denied his grassy paddock or breezy stall for the duration of that call.

Two weeks ago, Trent had been drifting from day to day in Town, a widower whom others would have said wasn’t coping well more than a year after his wife’s death. He’d spent his days and nights clutching the male version of the handkerchief, more commonly referred to as a brandy glass, though his difficulty hadn’t been grief per se.

Darius had, to put it gently, intervened in his older brother’s life.

“Darius is not a mile from our driveway, and I miss him already.”

Arthur, ever a sympathetic fellow, swished his tail.

Trent needed the damned mounting block to climb into the saddle, which was a sad commentary on his condition.

“Though how much sadder is it that I’ve written to the children only once?” The guilt of that mixed with a sense of abandonment at Darius’s parting to make the morning oppressive rather than pleasantly warm.

Arthur sniffed at Trent’s boot, which fit a damned sight more loosely than it should.

Trent passed the beast a lump of sugar. “Do not wipe your nose on my boot, sir. Even guilt can be viewed as progress when a man has stopped feeling anything.”

He arranged the curb and snaffle reins, pleased to note that his hands, after two weeks of regular meals and infrequent spirits, hardly shook at all.

In the interests of dawdling in the shade, Trent pointed the gelding toward the home wood, a great sprawling mess of trees, underbrush, bridle paths, and meandering streams. Small boys could spend entire summers in such a wood and never miss their beds. Of course, Trent was not a small boy.

Arthur’s ears pricked forward in the sun-dappled depths of the wood, drawing Trent’s thoughts away from shady hammocks and long, peaceful naps. He followed Arthur’s gaze and heard splashing from the largest pond on his property. Trent urged the gelding a few feet off the path and swung down from the saddle.

How he’d clamber aboard an eighteen-hand mount without a step was a puzzle for another time.

The horse obligingly cocked a hip and settled in to doze in the shade while Trent passed noiselessly through the brush. Another splash, then a female voice singing a folk tune—something about “green grow the rushes”—carried across the summer air.

The woman had a sturdy contralto, suited to a sturdy tune, and she was sturdy as well. Trent was taken aback to find her standing in the shallows of the pond happy-as-she-pleased, wearing only a summer-length shift—and a very damp summer-length shift at that. Her long, dark hair rippled down her back as she trailed a line-and-pole fishing rod across the water and sang—to the fish?

A dairymaid playing truant on a pretty summer day, or a laundress or other menial. She had the defined arm muscles of a dairymaid and the earthy ease with her body that Trent associated with females unburdened by the designation “lady.” While he stood mesmerized, she set the pole on the bank and, still standing in the water, began to plait her hair.

God above, she was a lovely sight. Trent resisted the urge—even urges had deserted him until recently—to tug off his boots, shed his clothes, and wade out to her side, there to do nothing in particular but be naked in the sunshine with her.

Sobriety could make a man daft, but not that daft. Rather than yield to his impulses, he stood among the trees and looked and gawked and looked some more, as if his eyes had been thirsty for this very image.

For anything that might make him wake up.

The lady was comfortable in the water, occasionally reaching down to splash herself. The shift became an erotic enhancement to bare flesh, outlining her figure, peaking her nipples, and creating a damp shadow at the juncture of her thighs. Her shape was thoroughly feminine—she had real breasts, real hips, not some caricature created by whalebone, buckram and clever stitching. When she lifted her arms to pin her braid on her head, the wet material shifted so one pink, tightly furled nipple slipped momentarily into view.

The image was purely, bracingly lovely. Trent mentally thanked the Widow Lady Rammel for causing him to be in that spot at that moment. He resolved to come fishing himself in the same pond and to vicariously join the dairymaid in her pleasures. The thought wasn’t even sexual—he hadn’t had those impulses for some time—but it was a sensual, happy thought.

And precious as a result.

He silently withdrew and walked Arthur some distance before using a handy stump to mount. Reluctant to leave the wood, he let the horse wander up one path and down the next until the hour approached noon.

“Come along,” he said, turning Arthur to the east. “We have a widow to condole. No more of your prevarications.”

All too soon, Trent was ushered into a pleasant family parlor done up all in cabbage roses; pale, gleaming oak; and sunshine. He steeled himself to endure not only the thoroughly feminine décor, but also fifteen minutes of social hell, tepid tea, and useless platitudes. When he turned to greet his hostess, however, the only thought in his head didn’t bear verbalizing:

She’s not a dairymaid.

Chapter Two

Ellie’s first thought was that Trenton Lindsey, Lord Amherst, had been to war. They’d been introduced at a local assembly several years before, and then he’d been an impressive specimen. Tall, fit, and possessed of dark, sparkling eyes to go with his dark, thick hair. He’d had an animal magnetism that Dane, for all his blond good looks, had lacked.

Now, Amherst was gaunt, his eyes shadowed, his clothing beautifully tailored but too loose and several seasons out of fashion.

“Lord Amherst.” Ellie curtsied and held out her hand. “A great pleasure. It’s too hot for tea, and the veranda will allow us some shade. May I offer you lemonade, hock, or sangaree?”

“Anything cold would be a pleasure.”

Ellie attributed his surprised expression to her sortie out of first mourning attire. She was in lilac, one of her favorite colors and one abundantly represented in her summer wardrobe. Dane would not have been pleased with her departure from strict decorum.

Which was just too perishing bad.

“We are neighbors, are we not?” Ellie inquired as he offered his arm and escorted her to the back terrace. The gesture reminded her that Amherst had married several years back. Thus, he sported the kind of understated good manners husbands usually acquired—some husbands.

“Your land marches with mine this side of the trees,” Amherst replied. “I don’t recall your gardens being this extensive.”

Had Dane even noticed the gardens?

“They used to be smaller, but I am not prone to idleness, and when the weather is fine, I like to be out of doors. Gardening provides the subterfuge of productivity and the pleasure of the flowers.” Then too, even new widows were permitted to dig in their own gardens.

He tarried at the door to the shaded veranda to sniff at a potted pink rose. “Which is your favorite flower?”

Amherst snapped off the rose and offered it to her, the gesture so effortlessly congenial it took Ellie a moment to comprehend that the rose was for her.

“Forgive me,” he said, his smile faltering the longer Ellie stared at the rose. “I do not socialize a great deal, and my small talk is rusty.”

Ellie accepted the bloom, careful of the thorns. “Please allow your small talk to crumble into oblivion. I am heartily sick of sitting through every recipe in the shire for restorative tisanes, and everybody’s favorite Bible passage for difficult times. At least a discussion of flowers is novel.”

Her escort was quiet. Had she disconcerted him or even shocked him? Maybe mourning went on so terribly long because months were needed to get the knack of being a proper widow.

A proper, discreet widow?

“You’ll not be planting lilies again,” Amherst said.

Because they were standing in the doorway, Ellie caught his scent.

He smelled wonderful—masculine but sweet, spicy, alluring, clean, intriguing. She could have stood there all morning, trying to sort and classify the pleasures of his scent.

Carrying a child did this—made the faculties more acute, more delicate.

She picked up the thread of the conversation. “I won’t be planting lilies, no. I’ve already put off blacks at home. Scandalous of me.”

“Sensible of you. The departed are gone. They don’t care what we wear.”

“You don’t think my late husband is peering down at me from some cloud? Commenting to St. Peter that I never was a very biddable wife?” That would be the least of Dane’s complaints.

“You didn’t force him onto that horse, Lady Rammel.” Amherst’s voice was so calm, so quiet, Ellie almost missed the keen insight of his observation.

She stayed right where she was, next to him in the shady doorway, while birds sang to each other in the nearby wood, and flowers turned their faces up to the welcoming sun.

“Say that again, my lord.”

“Your husband’s death was not your fault,” Amherst said slowly, clearly. “By reputation in the clubs, Dane Hampton loved to ride to hounds, loved the drunken steeplechase, loved to cut a dash on his bloodstock. He died doing what he loved, and he was lucky. You are lucky, in fact, that he died while frolicking with his hounds. His demise wasn’t your fault, and it wasn’t a bad death.”

Ellie wanted to make him say those same words all over again, but instead searched for a rejoinder.

And found none.

“Thank you.” She’d focused so intently on his words that it came as something of a surprise to see her hand still tucked in the crook of his elbow. Life was brimful of surprises recently. “These calls ought to come with a manual of deportment, and what you’ve just said should be the first required words.”

A smile threatened at the corners of his mouth. “I have no favorite Bible passage, and I’m fresh out of recipes for tisanes.”

“I like the verse about the lilies of the field, about neither toiling nor spinning, but still meriting the Almighty’s notice,” Ellie said, making herself step back. She liked Lord Amherst, liked that he wasn’t too self-conscious to stand near her, and that he didn’t spout platitudes. “Because that passage mentions lilies of the field, the scent of which now makes me ill, I’ll have to search out a new one.”

“You haven’t told me your favorite flower.” Amherst followed her onto the veranda, and Ellie silently conceded the point: Flowers were alive, Bible verses were not. Two different sources of comfort, one dear to her, one expected by her neighbors.

All of her neighbors, save one.

“Lily of the valley,” she decided. “For its scent. Roses, for sheer delicacy of appearance. Lilacs, for the confirmation they bring of spring, though they lack the stamina for bouquets. We’’re given so many worthy flowers, it’s hard to choose. Shall we be seated?”

He handed her into a chair at a wrought iron grouping at one end of the veranda, then took a seat beside her. Not across from her, but beside. How was it she’d had such a pleasant sort of neighbor all these years and had never become acquainted with him?

“Would you be willing to look over my gardens?” he asked, the chair scraping back as he arranged long legs before him. “I’ve allowed Crossbridge to suffer some neglect in recent months. I’m focused on the crops, the buildings, that sort of thing, but the estate once had lovely grounds.”

“Surely you have a head gardener, my lord?” But she wanted to do this. She wanted to make something pretty grow for her quiet, insightful neighbor and maybe make the acquaintance of his wife, if her ladyship were out from Town.

Friends being in shorter supply than she’d realized. When had she become so isolated—and why?

She also wanted to get off her own property and could slip over to Amherst’s gardens without anybody knowing she’d been truant from her grieving post.

Anybody but Dane. Ellie wanted to aim her face at the sky and stick her tongue out.

“Crossbridge has staff,” Lord Amherst said. “They have much to do simply holding back the march of time. The home wood encroaches on the pastures, for example, and my gardeners are busy clearing the fence rows, cleaning up several years of frost heave, and trimming the hedges. My flowers have been orphaned.”

On the third finger of Ellie’s left hand, a fat, shiny diamond caught a beam of summer sun. She took her rings off when she gardened.

“Dane left a daughter.” Heat flooded up Ellie’s neck, and she wondered if pregnancy also unhinged the jaw and the common sense. Amherst was a neighbor, true, and he’d likely know about Andy if he bothered to attend services, but he was a stranger.

A handkerchief appeared in her peripheral vision, snow white, monogrammed in purple, and edged with gold—also laden with his lovely scent. Ellie would not have suspected her slightly rumpled, out-of-fashion, overly lean neighbor of hidden regal tendencies, but his instincts were excellent.

“Perishing Halifax.” She snatched the handkerchief and brought it to her eyes, though she hadn’t cried for days. “Forgive me.”

“You are not the one who left a daughter,” Amherst replied evenly. “Perhaps the forgiveness is needed elsewhere.” He didn’t pat her hand, didn’t move any closer, didn’t murmur nonsense about time healing and God’s infernal will. He lounged at his ease two feet away and let her have her tears.

“Andy is eight.” Ellie blotted her eyes again. “Coriander. She’s young enough to miss her papa sorely. Dane was decent to her.”

Amherst still said nothing as Ellie defended Dane’s memory. Dane had been decent to Andy, once Ellie had staged the first and only row of their married life and insisted the child be raised at Deerhaven.

“People will tell you the grief eases, Lady Rammel, and in some ways, it does. Life tugs you forward, and you add good memories to the store of losses. The losses don’t cease hurting, though, not altogether.”

Ellie stopped dabbing at her eyes. “Perhaps you’d better keep a Bible verse or two in your pocket, my lord. Your honesty is particularly bracing.”

Also curiously welcome.

He inclined his head, not smiling. “My apologies. Grief is an old shoe that fits each foot differently, and I shouldn’t prognosticate for others. Keep the handkerchief.”

“My thanks.” Ellie took a surreptitious sniff of his heavenly scent and signaled the footman tactfully waiting a distance away with the tray. “What shall you have, Lord Amherst? Cold tea, hot tea, sangaree, hock, or lemonade. Alas, no tisanes.”

“Good company can be a tisane. I’ll enjoy some lemonade.” He didn’t smile with his mouth so much as he did with dark eyes that crinkled at the corners. Dane would have liked Amherst, which was something of a comfort.

Ellie garnished his glass of lemonade with mint and lavender, which seemed to make it ever so much more palatable. When she’d poured for herself—now, lemonade appealed—she held up her glass in a toast.

“To consolation.”

He politely raised his glass a few inches and sipped, his expression considering.

“You’ve a rebel in your kitchen. I’ve come across the mint with lemonade before, but not the lavender.”

Ellie sampled her drink, finding it exactly to her taste, rather like Lord Amherst’s brand of condolence call. “My own recipe. Not everybody likes it. Andy says I’m daft.”

“An outspoken young lady. One wonders where she might have acquired such a trait.”

“Are you teasing me?”

“On page forty-two of the manual, you will find that teasing is required.” Amherst’s tone was grave. “Right after ladylike sniffles and before a recitation of platitudes.”

“Useless platitudes.” Ellie couldn’t help but smile, because teasing was indeed a consolation. “Were you sincere in requesting my help with your gardens, or was that a recommendation from the manual as well?”

He held the wet sprig of mint under his lordly nose, and Ellie realized he might tease her, but he wasn’t a man given to simple banter. Dane had bantered easily and merrily. She’d found it charming—at first.

“The request was sincere. I’m short of staff, and the gardens are, of necessity, a low priority. I would not want to intrude on a time of grief, but I can use the help. Beyond a certain point, even the most well-designed garden can’t be rescued, and my plots are approaching chaos.”

The best-planned marriages could reach the same state of untenable disrepair all too easily. Ellie liked that his lordship would admit he needed help, though it threw into high relief that Dane had not needed her, except to produce an heir. In his lifetime, that priority had been untended to.

“Chaos sounds intriguing,” Ellie said. “Weather permitting, expect me on hand tomorrow. What time suits?”

“It’s cooler in the morning.” Amherst removed the lavender sprig from his drink and placed it on the tray, when Dane would have either pitched it into the pansies or consumed his drink, garnish and all. “We’ll tour the grounds, and you can give me your first impression. I’m usually off on my rounds by eight.”

“That will suit.”

Nothing in his tone suggested he was merely being polite by making this request, but Ellie still had a sense her neighbor was somehow dodging. She signaled the footman again. This time, he brought over a tray bearing a cold collation of meat, cheese, condiments, and sliced bread. “I thought you might enjoy some sustenance, my lord. May I fix you a sandwich?”

Amherst set his drink down and picked up the lavender. “I’ll pass, but you should eat, my lady.”

“You truly don’t mind?” She did momentary battle with a craving for a bite of cheese—a sharp cheddar with dill would be splendid. “I’m famished, if you must know, but then, I lack the petite dimensions of a proper English beauty and probably always will.” Swimming and fishing always put a sharpish edge on her appetite, even as they soothed her nerves.

An odd smile crossed Amherst’s features. Even gaunt and dispensing sympathy, he was attractive, particularly when he smiled. Then too, there was his scent, his subtle humor, his gentlemanly manners. If all that weren’t enough to endear him as a neighbor, he was also…kind.

Amherst twiddled the lavender, the scent rising on the breeze, while Ellie prattled on about flowers and consumed a real sandwich—not some stingy gesture with watercress and a pinchpenny dab of butter. All the while, as he made appropriate replies and sipped his drink. Ellie sensed that he drew pleasure simply from watching her eat.

Dane might have winked at her and joked about getting her a larger mount.

Eating for two was less guilt-inducing than eating for one. When Ellie rose to see her guest out, though, she stood too quickly and had to seize his arm while the sounds of the summer day faded behind an ominous roaring.

“Steady on, my lady.”

He was stronger than he looked, bracing her against his body until the dizziness faded and Ellie’s head was filled once again with the lovely scent of his person.

“Take your time,” he murmured, making no move to step back. “Shall I call for a maid?”

“I’m fine.” She’d been far from fine for at least two months, and possibly for much longer than that. “Though perhaps when you’ve gone, I might have a lie down.”

He peered at her, and Ellie became aware—more aware—that he was quite tall, taller even than Dane, who’d been proud to top six feet. And wasn’t that like a man, to be proud of something he’d had nothing to do with, no control over whatsoever?

“Let me see you into the house. Those naps can be a trap.”

“I beg your pardon?” Ellie let him slowly promenade her down the veranda, his arm snugly around her waist, her hand in his. They were barehanded, because they’d been eating. His firm grip on her hand and waist reassured her more than she’d like to admit.

“The sleeping,” Amherst went on. “Drifting from day to day is easy, and then you don’t sleep at night, and the waking nightmares are as bad as the ones you’d have were you slumbering. Then you’re so useless the next day, you’re taking another nap and up all night yet again.”

Ellie digested that and continued their measured progress toward the house.

“You’ve lost someone dear,” she concluded, detecting a slight hesitation in his gait.

He withdrew the sprig of lavender from his pocket, but at some point, he’d fashioned it into a circle the diameter of a lady’s finger. He presented the little garnish to her with a courtly flourish.

“Haven’t we all lost somebody dear?”

* * *

“Trenton is doing better.”

Darius Lindsey’s hostess was one woman he didn’t dare lie to. The dowager Lady Warne was a connection formed when Leah Lindsey—Darius and Trent’s sister—had married Nicholas Haddonfield, Earl of Bellefonte. When Nick had joined the family, he’d brought his eight siblings and his grandmother along. With few exceptions they boasted commanding height, lightning intelligence, and a zest for living that made them individually and collectively overwhelming on first impression.

Lady Warne held out a plate of ginger biscuits, and Darius took two. She kept the plate before him, and he took two more.

“Define ‘doing better,’ my boy.”

“He sleeps for more than an hour at a time, really sleeps,” Darius began, searching for compromises between truth and fraternal loyalty. “He’s stopped drinking, except for a glass or two of wine with dinner. He rides again. He’s writing to family and not shut up at Crossbridge the way he was in Town.”

Lady Warne ran an elegant finger around the rim of her glass. “For some of us, the best medicine is the land, the beasts, the out of doors. Not very aristocratic, but there it is, and quite English. Can you stay with him?”

No, Darius could not stay with his brother, and not only because Darius had promised to spend the summer in Oxfordshire helping Valentine Windham reclaim an estate from ruin.

“Hovering won’t serve. Trent might have needed somebody to haul up short on his reins, but he’s on his own now. Many a man has vowed to swear off gin, or gambling, or carousing, and two weeks later he’s at it worse than ever. Trenton has a long way to go, physically, if nothing else.”

Lady Warne’s finger paused. “Amherst’s health is poor?”

“He’s a ghost.” Darius could think of no more accurate word. “Five years ago, I would have put Trent up against any dragoon in the king’s army. He could ride, shoot, handle a sword, or quote Shakespeare with the best of them. By comparison, he’s feeble now. If the Crossbridge steward hadn’t run off with the housekeeper, Trent might still be drifting around the town house, skinny as a wraith and twice as pale.”

Run off, and taken a good sum of household money with them, so lax had Trent’s supervision become.

“Five years ago, your brother hadn’t capitulated to your father’s choice regarding the succession.”

Lady Warne had the elderly ability to ignore tender sentiments, and she was right: Paula—or her fat settlements—had been the Earl of Wilton’s choice, and Trent, ever dutiful, had graciously recited the appropriate vows.

“Trent has been through a rough patch, but he’s stubborn, when he has a reason to be.”

“Unlike others.” Lady Warne’s smile was devilish. “Others are stubborn for the sheer fun of it.”

“Is Emily proving stubborn?” Darius set his empty plate down, as if his little sister might be lurking behind the curtains, watching him eat a ridiculous number of fresh, warm ginger biscuits.

“She is sweet but sensible,” Lady Warne said. “Particularly now that she’s out from under your father’s boot heel. If she doesn’t present herself shortly, though, I will wonder if she hasn’t perfected the art of the feminine dawdle.”

“Wasted on a brother who wants only to take her for a ride in the park.” And to make sure she was behaving herself.

“Let me fetch her.” Lady Warne rose gracefully, leaving Darius to sip cold cider and wander the room. He’d been reasonably honest with Lady Warne, for she was old, and as sharp as the rest of her clan. Trent was sleeping, some. He was eating, a little. He was riding short distances, but only because a man without a land steward could either tramp all over his acres or ride a horse, and Trent wasn’t up to the tramping.

Those glasses of wine at dinner—three or four of them—were consumed with desperate relish, too. Darius had longed to hover, longed to order the servants to empty every bottle of spirits, to put Trent on a schedule of riding and walking and a diet of good summer fare.

But barging into another man’s life, destroying his dignity, and deciding his fate was the province of the Earl of Wilton, not his grown children. Darius had done what he could for Trent, then withdrawn to tend to other responsibilities.

He owed Trent the kind of faith Trent had shown him. Trent claimed Darius had saved his life by hauling him bodily down to Crossbridge, but in Darius’s mind, that was simply the return of a favor owed.

***

Arthur, being six feet tall at the withers and gelded, stood biologically and physically above much of what made life trying. This made him an adequate conversationalist for Trent’s return through the woods.

“And there I was,” Trent muttered, “trying to make small talk with a widow, for the love of flowers.” A papa of small children developed strange epithets. “A woman not three months past the loss of her spouse, and what do I do? Damned near put her in a faint, poor thing. She ought to burn my handkerchief and bury the ashes at a crossroads, mark me on this.”

Arthur took a nibble of a passing branch.

“She’s pretty,” Trent went on, ducking to avoid the same branch. “Prettier the longer you look at her, and believe me, horse, I looked. Sat up and took notice.” That had been the strangest sensation, like dreaming he was waking up. The longer Trent had listened to Elegy Hampton’s voice and watched her hands and face, the more alert he’d become, but slowly, like shaking off a drug or a hard knock to the noggin.

He hadn’t had the same peculiar sense when he’d seen her in her shift singing to the fishes. That had been a different pleasure altogether, though equally unexpected.

“And God help me, she’ll be on the property tomorrow morning expecting me to converse civilly and offer hospitality.”

A simple call between neighbors shouldn’t overtax him. He knew the civilities, knew them in his bones, because excellent manners were the first arena in which he’d taken on besting his father. The first of many.

In the early afternoon heat, the lure of a nap pulled at him strongly, but in keeping with his determination not to scare his brother—Trent’s label for what had been happening in his life before this forced remove to the countryside—Trent handed his gelding to a groom and ambled off on a slow walk instead.

Because, damn it all to hell and back, one quiet hack of a morning and a slow walk were about all he could manage.

His footsteps took him through the once-impressive gardens behind his manor house. The sun should have felt oppressive, but when he stopped to rest—to think—on a bench, the soft heat on his face bore the benevolence of an old friend’s voice heard after long absence.

The gardens were in bad condition, neglected and overgrown past open rebellion. Some beds had succumbed to weeds. Others had been taken over by one of the hardier flowering species, and the whole business gave off an air of a cheerful botanical riot.

“Even my flowers…” Trent muttered, then caught himself. Talking to a horse was one thing, talking to oneself quite another.

“Thought you were dozing off,” came a voice from behind a twelve-foot-high lilac bush.

“Show yourself, Catullus.” Trent gave up the pleasure of the sun on his closed eyelids. “I do not pay you to skulk.”

Cato emerged from the thicket of greenery, a sprig of mint dangling from the left corner of his mouth.

“Hiding from Cook, are you?” He seated himself beside his employer uninvited and leaned back to enjoy the sun right along with him.

“She tortured me with menus before breakfast and hinted mightily that a single gentleman ought to entertain when he’s in the country of a summer.”

“I entertain plenty,” Cato replied, twirling the mint between his teeth. The oral gymnastics and the comment combined in a manner somehow lewd.

“You entertain the tavern maids.” Trent’s stable master was big, good-looking in a dark-haired Irish way, well muscled, and a thorough scamp with the women—and the ladies. His speech held a hint of a brogue when his emotions ran high or he was foaling out a mare, but his diction and word choice were otherwise refined.

Not quite Eton, but public school at least and maybe even university. The contradiction of a gentleman’s education with a horse master’s vocation hadn’t struck Trent before.

Not much had struck Trent…before.

“Why aren’t you laboring away in my stables?” Trent asked, settling lower on the bench.

“Work’s done for now. You need to make a decision about your mares.”

“What decision?”

“It’s nigh June, your lordship.” Cato’s voice held a hint of irritation. “You wait any longer to breed them, and they’ll be foaling in the worst of the heat and flies next year, with the best of the grass over and done. You can let ’em yeld this year, but a stable master likes to know these things, so he can put a few of the ladies in work. Then too, Greymoor’s stud has a dance card to manage.”

“Work a mare?” Trent snatched the sprig of mint from between Cato’s lips and tossed it aside. He was irritated with himself more than Cato, because even following a conversation took effort when a man kept picturing a certain damply clad widow on a fishing expedition.

“A mare,” Cato said with exaggerated patience. “A lady’s mount, by any other name, perhaps even a mount for a sister, or sister-in-law, or daughter. You’ve seen the like, once or twice?”

“I have.” Trent hunched forward and forced himself to apply his sluggish mind to the question on the floor: What would Lord Amherst like to do with the mares at his country estate, if anything?

Turn them loose in the home wood and spend the summer wandering after them.

“You weren’t this stupid two years ago,” Cato remarked when the silence lengthened.

Or perhaps the mares could trample the stable master.

“You are big enough and fast enough to make outrageous comments like that, Cato,” Trent replied placidly, because Cato was goading him for some purpose known only to himself. “Don’t think getting a rise out of me will provide a result you’ll enjoy.”

Cato shrugged broad shoulders and grinned a charming, robust fellow’s grin. “Here in the wilds of Surrey, one finds one’s entertainment where one can, your lordship.” He rose with the easy grace of the strong and fit, though his observation went far beyond impertinent. “Let me know what you decide.”

As Cato strode off, Trent’s foot, independent of any decision by its owner, shot out and neatly tripped the stable master, who was laughing outright when he regained his balance.

Cato saluted with two callused fingers. “Better. Not your best effort, but a start.”

Arthur would probably agree with that assessment.

Trent did, too.

Chapter Three

The weather was glorious, his neighbor punctual, and Trent in a toweringly bad mood as a result. What—what?—had possessed him to invite this Lady Rammel onto his property, much less offer her a gardening project that could stretch for weeks? Even as he knew his anger was irrational—and he knew staying busy was a means of survival early in a bereavement—he resented the way she sat her horse, as if born on its back. He’d ridden like that, once upon time. Darius still rode like that. Cato road as if statues should be erected on his model alone.

And did Lady Rammel have to fill out her habit so…robustly? He used to take pride in the cut of his clothes and the elegance of his turn-out.

Did she have to damned smile at his useless stable master when Cato appeared from nowhere to help her off her horse?

“You’re acquainted with my stable master?” Trent managed as Lady Rammel’s mare was led away.

“He and Dane were thick as thieves in hunt season.” She beamed as if this was famous good news. “They could natter on about cubbing and tail braiding and line breeding and heaven only knows what else for hours. I expect Mr. Spencer will miss Dane when the hunting starts up in the fall.”

Mr. Spencer, being Catullus Sandringham Spencer, or Cato, to his many adoring familiars. Trent hated riding to hounds on general principles.

Also because his father thrived on blood sport.

“What have you done with Dane’s horses?” Trent heard himself ask.

Could he have fashioned a more gauche question to put to a huntsman’s bereaved widow?

Lady Rammel’s smile dimmed. “Odd you should inquire. Dane’s cousin is coming up at the end of the week to take them in hand. The stable lads are going through another round of mourning as we speak.”

“His cousin?” Trent offered her his arm and searched the viscous morass of his memory for who that might be. Hampton had been titled, and somebody was no doubt dancing a jig on his grave in consequence.

“Drew,” she said, with no inflection whatsoever. “Dane called him Dutiful Drew, and not only behind the poor man’s back. Drew is the heir and takes his duties seriously.”

“Is he putting your dower property to rights?”

“My dower…” Hers brows knit, then her smile reappeared. “I suppose, but I’m happy at Deerhaven. Papa owned Deerhaven outright and set it aside for me in the settlements, so here I’ll stay.”

“Lucky for me,”—the sentiment was genuine, though sentiments had also, until recently, gone into eclipse along with Trent’s urges—“and for my flowers.”

What tripe.

As the lady chattered on and they made several slow circuits of his gardens—he kept up with Lady Rammel easily—Trent began to enjoy his bad mood. Tripe? Tripe? How long had it been since he’d indulged in such a word, even in the privacy of his thoughts?

He cast his mental hounds, and other words came to mind, bold, articulate terms like asinine, fatuous, and puerile, words a man could toss out with some heat and substance behind them. He started to put all three in a sentence and searched for an appropriately colorful verb to hitch up to them when he realized his companion had fallen silent.

Some time ago.

Shite. “I beg your pardon, my lady.”

“For?”

Trent kept his eyes forward. “My conversation has deserted me, which would be no great loss, except I’ve put yours to flight as well.”

“I’m listening to the exchange between your wanton flowers.”

Wanton was a fine old word. “What are they saying?”

“The irises are complaining their slippers are too tight,” Lady Rammel informed him. “While the roses need a good hair combing but are planning to parade some splendid finery in a few weeks, nonetheless. The Holland bulbs are tired of dancing and ready for a supper break. The daffodils wish everybody else would hush so one could get some rest.”

“Are all my flowers female?”

“Lilacs have woody stems, and they grow quite vigorously, so I think of them as masculine.”

Woody…old words, vulgar ones, tripped through Trent’s head, and it now became imperative that he keep his eyes front.

“May we sit a moment here?” Lady Rammel dropped his arm and settled on a shaded bench, the same one Trent had occupied with his stable master. “This had to have been your scent garden, and it’s worth lingering over.”

Trent settled in beside her, happy to note he hadn’t needed the respite—not quite yet.

His companion was quiet, apparently content to inhale the effects of a scent garden growing riot on a summer morning. Beside her, Trent’s bad mood had eloped with his conversation, leaving him acutely sensitive to the pleasure of simply sitting beside a pretty woman in the morning air. She wore lavender well for a lady of her coloring, and she hadn’t minced along beside him as if her full corset were torturing her bones.

He endured the most peculiar impulse to take her hand.

Lady Rammel closed her eyes and tipped her head back. “Andy wanted to come with me this morning. Her situation can be difficult.”

“Difficult?” Trent sorted through the implications, while noting that Lady Rammel had long eyelashes. “She’s an only child?”

“She’s an illegitimate child,” Lady Rammel replied, her tone mild, even weary. “One wants to protect her from unnecessary distress, but not overprotect.”

The urge to take the woman’s hand persisted. She had freckles over her knuckles, suggesting she didn’t always wear gloves when she gardened. “You are wondering if I would censure you or the child, should you presume to allow her to accompany us through my gardens.”

“Something like that.” She opened her eyes and studied a tuft of silvery green lavender flourishing before some tall plants Trent didn’t know the name of. “Would you censure me for bringing her?”

Of course not, but what was Lady Rammel really asking? A man who hadn’t spent a long year clutching the brandy decanter would have puzzled out the subtleties easily.

“You wonder about the girl’s welcome, because her father is no longer around to insist she be treated civilly?”

“Yes, though her father is no longer around to gainsay my decisions, either,” Lady Rammel countered, the first hint of steel threading her tone.

Trent regarded the pretty lady beside him and permitted himself a flash of ire at idiot spouses who left children half-orphaned, particularly for something as foolish as a drunken steeplechase.

Though he’d left his own children more than half-orphaned for the dubious company of the brandy decanter, hadn’t he?

“Miss Coriander is welcome at Crossbridge.” Trent rose and offered Lady Rammel his hand. “I’ve a pony she might put to use, come to that. The poor beast hasn’t been exercised to speak of in years.”

“Miss Coriander will take up residence here if you let her know you’ve a pony going begging.”

“God in heaven.” Trent shot her a stricken look and stopped in midstride, his hand still wrapped around hers. “If you don’t want her to ride, I will understand. My uncle took a bad fall, and my aunt—”

She stopped him with a shake of her head.

“Dane overfaced his horse, overindulged his thirst, and overestimated his skill in bad footing. Andy is a more prudent sort, for all she’s only eight. I’m sure she’ll take to your pony. In fact, even Dane would agree—would have agreed—it’s time she met a few ponies.”

“Then I must introduce you to Zephyr.” Trent turned them toward the stables. “I adore her. She’s the one female who isn’t impressed with Cato’s charms, unless it’s feed time.” He strolled with Lady Rammel along the walk, and when he realized he was still holding her hand, he decided to continue in that fashion rather than create awkwardness calling attention to his blunder.

Lady Rammel was friendly with the pony, who flirted back shamelessly, suggesting the little beast was partial to women, as some equines were. That necessitated introducing Lady Rammel to the pony’s neighbors and confreres, including Arthur, who also flirted without any dignity whatsoever.

Lady Rammel scratched Arthur’s big red nose. “He has such a kind eye. A gentleman, this one, and well named for royalty.”

“He was named for a cloth doll my sister had when we were quite young.”

The only toy Trent could recall Leah owning, in fact.

Lady Rammel dropped her hand. “If you value your free time and your ears, you will not ask Andy about animals. She has a menagerie of zoological rag dolls, and they all go to high tea, picnics, story hour, and so forth.”

The recitation sent a spike of homesickness through Trent, for his children, especially for little Lanie.

“An imaginative young lady,” Trent said, as he strolled Lady Rammel right up to the house, though—had he been capable of rudeness—he might have called for her horse when they were in the stables. “May I offer you some sustenance now that you’ve spent half the morning tramping all over my domain?”

“You may.” She beamed at him again, that smile he was starting to watch for. Had Dane Hampton, as he lay gasping his last in the mud beneath a gate, longed for one more glimpse of that smile?

For the first time since arriving at Crossbridge, Trent was smitten with spontaneous gratitude, rather than the manufactured variety. His stable master, cook and butler hadn’t gone a-maying like his steward and his housekeeper, and he had sufficient staff that he could entertain a neighbor on an informal call.

He was alive; he could move about under his own power; and he had three lovely children. Any one of those was a substantial blessing, and he’d nearly allowed them all to slip from his grasp.

So he could clutch a brandy decanter?

“We’ll have a reprise of breakfast,” Trent said, taking a place beside Lady Rammel at a wicker grouping under a spreading oak. “Or for some of us, the first verse.”

She eyed him up and down in a thoroughly uxorial fashion, sending a wash of heat over Trent’s cheeks. “You haven’t eaten yet?”

“One becomes involved in the day, and I’m adjusting to country hours and country fare.” To eating regularly, in any case.

“What’s your favorite source of sustenance?” She settled in as if getting comfortable before interrogating him, though it wouldn’t do at all for Trent to give his honest answer.

“I’m partial to sweets.” Brandy was sweet. Sweetish.

She wrinkled her nose. “Not a thick, bloody beefsteak?”

Trent glanced around, making sure the footmen were not in evidence. “Just because you were married toRammel doesn’t mean you had to adore his every choice and preference. Or any of his choices and preferences, for that matter.”

Her ladyship found it necessary to rearrange the drape of her skirts. “Have you been reading the manual again, my lord?”

They’d start breakfast with a serving of honesty, because Rammel had not appreciated his wife, of that much Trent was certain.

“I loved my mother,” Trent said. “She doted on us, preserved us from the worst of my father’s temper, and wasn’t above pitching a cricket ball to her sons when Papa was away. But she was stubborn, had a selfish streak, and could be close-minded. Even as I understood that she needed determination to survive her marriage, I could still acknowledge those traits weren’t always healthy.”

“How long has she been gone?”

“Years. She was ill for some time first.”

“I wonder about that.” Lady Rammel resumed smoothing her skirts. Had she been the one to sew all those rag dolls for Miss Coriander? “I wonder about whether a little time or a lot of time is better than death coming for you in an instant.”

“And then,”—Trent reached over and stilled her hand—“you wonder better for whom.”

“I don’t miss the things I thought I would,” she said, her gaze on Trent’s bare hand. “I do miss things I thought of as…obligations.”

Sex. She’d been a dutiful wife; Rammel had been a healthy young husband, and she missed the sex. How Trent wished he’d lost a wife with whom he missed something so basic.

“You miss standing up with him in church?” Trent suggested as the footmen appeared with several trays.

She snorted. “Dane in church? He was a hatches and matches Christian, not overly fond of regular services. He did his part for the local living, and he tarried long enough in church to be shackled to me.”

“He told you he felt shackled?” Rammel deserved to be trampled in the mud all over again if he’d taken that low shot.

To a man who’d been married for five years—not shackled, not even to poor Paula—Lady Rammel’s smile looked forced. “Of course he didn’t use those words. Shall I serve?”

“Please.”

She was at home with the duties of a hostess, of a wife, and she had the knack of turning the conversation back to innocuous topics—his flowers, Miss Coriander’s clever governess—while she fixed him a plate of scones and fresh strawberries to go with his gunpowder. For his part, Trent let himself enjoy the lilt of her contralto wending through his senses as her hands dealt with the tea service.

Unbidden, the sound of her singing, half-naked in the woods, stirred in his memory.

He wasn’t particularly hungry, even with all their walking, but he ate to be polite. His guest, however daintily, ate to enjoy her food.

“Is there anything more pleasurable on the palate than perfectly ripe fruit?” She chewed a bite of strawberry, her eyes closed, then smiled as she swallowed. “I’m being tiresome to bring it up, but I can’t help but feel as if I’m supposed to fade away, oppressed by grief, unable to eat.”

“Some people grieve that way,” Trent said, eyeing his buttered scone. Other people drank and drifted while they neglected themselves and their children.

“I am disappointed in Dane for dying,” she replied, munching another strawberry. “I am quite sorry for him, but the great black cloud of overwhelming loss has yet to engulf me for more than a few days or a few hours at a time.”

Trent put his plate down because he knew exactly what his guest was asking and had asked it himself until the question had made him sick.

“Lady Rammel, if that great black cloud comes calling, I hereby admonish you to have a good cry, then run like hell, gorge yourself on strawberries and flowers and chocolates, wear bright colors, dance on the lawn, and sing at the top of your lungs.”

Or fish in my pond, which he could also see her doing.

“I don’t think Vicar would support your prescription,” she said, her smile fading.

“Vicar wasn’t married to the man,” Trent said in exasperation. “How did Dane remark your first anniversary?”

“He was off shooting in Scotland.” She picked up a large, perfectly ripe, red berry, but didn’t eat it. “He wasn’t about to miss the opening of grouse season two years in a row.”

“What did he give you for Christmas last year?”

“He…something. Exactly what escapes my memory.”

“What did he give Miss Andy?”

“A cloth horse doll,” she said slowly. “That I made for her.”

“Do you take my point?”

She put the strawberry down. “I don’t like your point. If you’re telling me I’m grieving in proportion to how I loved my husband, perhaps I should be offended.”

“My apologies.” Trent should have stuffed a scone in his maw, or remarked something inane about the weather, but instead he served up more honesty. “Though I risk giving offense, I’m suggesting you’re grieving in proportion to how you were loved.”

The emotions on her face were painful to see, anger and disbelief at his rudeness, then shock, more disbelief, and a dawning hurt.

Trent had hurt a woman, who’d done not one thing to deserve it—before breakfast was even off the table. “Forgive me. I should not have spoken thus.”

“You know more about this grieving business than you should,” she replied, her features composing themselves.

“Maybe more than anybody should. May I have another scone?”

He held out his plate, hoping desperately to distract her even if it meant he’d have to choke down the damned scone. When she left, he would find a brandy decanter. Yes, it was morning, and yes, he’d done better lately. But this…

She fixed him another scone, sliced it cleanly in half and slathered butter on both halves. “Jam, my lord?”

“No, thank you.”

She passed him the plate, then turned her face away. By the funny little hitch of her shoulders, Trent knew, for the thousandth time, he’d inspired a woman to tears.

***

Until his cousin Dane’s untimely death, the ladies had found Drew Hampton charming and occasionally worth a tumble or a waltz, though he was merely an heir presumptive, not an heir apparent. In the great whirling circus of titled society, he was barely worth a mention, particularly when Dane—handsome, robust, witty, and generous—had been unlikely to die for at least another two score years and had married a robust young lady well suited to childbearing.

Drew eyed the canopy of his vast bed and considered having winged pigs embroidered thereon.

“What has you smiling?”

His romping partner of the morning, Lady Somebody or Other, tiptoed her fingers across his naked chest, then headed south.

“The thought of a hearty meal following our exertions,” he replied, trapping her wandering hand. “Shall I have a bath sent up for you?”

The buxom brunette—when relieved of her clothing, she answered cheerfully enough to Crumpet, Angel, or Darling—ceased her southerly peregrinations. “You’re serious.”

“I’m hungry. I’ve appeased your other appetites and mine, so now food is in order.”

Women, apparently, didn’t grasp that sequence of events as readily as men did.

“I should be grateful you didn’t roll over and go to sleep.” The brunette sat up and swung her feet off the bed, accepting the dressing gown Drew handed her. “You really need to work on your charm, sir.”

“You found me charming enough twenty minutes ago.” Drew set about dressing himself and glanced at the clock on the mantel—fifteen minutes ago, to be precise.

“You’re honest. That has a certain backhanded charm,” the brunette allowed, her smile reluctant. “You’re wishing I’d take myself off, aren’t you?”

“I appreciate directness in a lady, particularly in the bedroom.” Drew offered a hint of a smile to soften the sentiment, though he truly was in want of sustenance.

She rose and started organizing the clothing she’d tossed over a chair earlier.

“As subtle as you are, one wonders how I was lucky enough to merit your attention.” Her actions were abrupt, a minor display of pique Drew tolerated rather than provoke her further. He did need to work on his charm, or he would have needed to work on his charm, if he’d had any to start with.

She’d been a willing romp, so Drew let her get dressed in peace, obligingly doing up her stays and hooks. She was wise enough not to complain, and he’d send her flowers tomorrow, but their encounter was exactly as he’d intended it to be.

And likely far less than she’d hoped it could be.

All the more reason to observe the civilities and see the lady to her waiting town coach. He politely bowed over her hand and thanked her for her company, then took himself back to the comfortable confines of the Rammel town residence. He passed through the kitchen, letting the scullery maid know he’d take a tray in the library. In the hallway, he caught sight of himself in a mirror hung over a cherry-wood sideboard.

The fellow in the mirror was tired, not quite tidy, and going a bit hard around the eyes and mouth.

Less than three months after Dane’s death, and he was behaving more like Dane, looking more like Dane—more arrogant, more self-absorbed, though Dane’s blond, muscular appearance had been at variance with Drew’s taller frame and dark coloring. Dane hadn’t been a bad man, but neither had he been a good man. He’d been a viscount, a title, and no better than he had to be, as with most of the breed.

If dear Ellie were not carrying, Drew would soon become the next Viscount Rammel, and the thought brought no joy.

Dane, in typical viscount fashion, hadn’t spared the coin when it came to his pleasures, leaving a stable of fine hunters to be dealt with. The thought gave Drew a pang, because it meant he’d be traveling down to Deerhaven the following day to see about the horses.

And that meant facing Ellie, who was his responsibility as well. Too bad there weren’t broodmare sales for slightly used viscountesses.

He turned his back on the mirror, for that thought was callous even for him, even when not one living soul stood between him and his recently deceased cousin’s title.

***

Men were so much easier to understand than women. If a man was upset with his fellows, he put up his fives, delivered a blistering set-down, called out his detractor, or ignored the whole business with cool, manly disdain.

Trent dug for his spare handkerchief, for women, unfathomable creatures, cried. For the entire five years of his marriage, Trent had been bewildered, resentful, and then downright despairing at his wife’s tears. Nothing stemmed the flow of Paula’s upset, not time, not solitude, and most assuredly not reason.

Reason, he’d learned early, was the surest way to provoke her further.

Lady Rammel blotted her eyes with the handkerchief he’d given her earlier in this burdensome morning, but when he reached out to pass over the reinforcements, she took his hand instead and used it to haul herself right over next to him on the wicker settee.

She bundled into his side, weeping against him in quiet torrents, the sound tearing at his composure as visions of brandy decanters danced in his head. His arms went around her even as he bent his head to try to decipher what she was saying.

“I’m s-sorry,” she whispered.

“Don’t be inane.” Proximity to her was the price he paid for having been so ungallant with her grief, and the lady wasn’t about to turn loose of him.

“Do you ever hate her?”

He’d bitterly resented Paula, for the middle two years of their marriage. “Who?”

“Your mother. The one who lingered and was stubborn.”

That mother. “Nearly.” He would worry about his unfilial admission later. “She inveigled promises from my brother and me, promises with lasting and hurtful consequences, and at certain times, if I didn’t hate her, I came very close.”

“And she was your mother.” Lady Rammel nodded, apparently satisfied with his answer, and the gesture waved her silky dark hair against Trent’s cheek. He resisted the urge to bury his nose in that feminine treasure, but allowed himself an inhalation of her fragrance.

“You’ve a different scent today from yesterday.”

“I have my moods. Some of them inconvenient.” She shifted as if to gather herself away from him, but Trent stopped her.

“Stay.”

She heaved off another Sigh of Sighs and relented, turning her face into his shoulder. “Earlier, when I said I missed the obligations?”

Trent’s fingers traced over the knuckles of the hand she rested against his chest. “I recall the comment.”

“I miss paying his bills. I miss scolding him for getting mud all over my carpets and wearing his boots to table. I miss him coming in from the hunt field, bellowing for a toddy and his slippers. He wasn’t company, exactly, but he was there.”

The litany was pathetic in some ways, but at least she had a list, prosaic as it was. “That you miss him is good, a blessing.”

She snorted, a ladylike explostulation of self-derision. “I missed him when he was alive. I didn’t always like him, but I missed him.”

For her, this was Progress. Trent laced his fingers with hers and offered her hand a consoling squeeze rather a platitude, Bible verse or tisane.

“I did not matter to my husband half so much as his favorite hunter,” she said, with a tired sort of asperity, “but I comforted myself with the fiction that I did, that I might matter to him someday.”

When she’d become the mother of Rammel’s heir?

“You matter to Andy,” Trent said, and that must have been the right thing to say, because along his side, her body gave up a remnant of defensive, resentful rigidity.

“I do. You’re right about that, and it’s important.” She smiled at his much-abused handkerchief, and a tightness in Trent’s chest eased.

That smile held something secret, female and sweet, a little maternal, but not without mischief. Trent’s hand, the one that had been linked with hers, lifted as if to touch her smile, but common sense caught up with him, and he settled for returning his rambunctious appendage to his thigh.

Breakfast should not have concluded with his guest in tears, making awkward confessions as she wrinkled his handkerchief, but he made no move to shift away, and neither did she. In fact, as they lingered on the settee—lingered cuddling on the settee—Lady Rammel grew heavier and more relaxed against his side. Her eyes soon closed, and her breathing fell into a slow, steady rhythm.

The deuced woman had fallen asleep against him.

He tucked her more closely to his side, stole a whiff of her hair, and glanced at the clock—though he had no appointments, pressing or otherwise, on his calendar. Seven fragrant and peaceful minutes later, his companion stirred, but she didn’t bolt upright, expressing ladylike horror at her behavior.

She…nuzzled at him. Nuzzled. Then gave a soft, sleepy sigh and drifted into stillness.

Arthur nuzzled Trent’s pocket for treats. The house cat occasionally nuzzled Trent’s chin to interrupt his reading or demand to be let out. A nuzzling female was novel and dangerous and stirred urges both protective and unruly.

Lady Rammel sat up slowly two minutes later, chagrin on her pretty features. “Perishing Halifax. I have lapsed mightily, haven’t I? What must you think of me?”

“You have napped, a little.” Trent tucked back a lock of her hair that had tried to snag itself on his lapel as he’d retrieved his arm. “Would a glass of lemonade appeal?”

“Yes, I believe it would, along with a nice big hole in the ground to conveniently swallow me up and rescue me from further apologies. A vow of secrecy would be appreciated as well.”

“My daughter is a firm believer that after every bout of tears must come a restorative nap.” Also a cuddle. Trent rather missed Lanie’s cuddles. “Napping, in my daughter’s case, is a constructive habit. Her way of leaving the scene of the drama.”

“You’ve a daughter?”

“Just the one. I’ve sent my dependents to visit my sister, but my daughter can put the whole household into an uproar when she’s peckish, or tired, or happy, or cranky.” Trent shifted to a seat at a right angle to his guest, intending the distance to support her bid for composure.

Also his bid for composure.

The lady yawned with a sleepy sweetness. “Andy hates her given name. Her mother was a cook, and Andy thinks the name an insult. When the child is determined on her pique, we all hear about it at length.”

She fell silent, smoothing the hanky slowly against her thighs for a moment before raising her head and peering over at Trent. “Having disgraced myself in your presence, my lord, may I make a further imposition?”

“Of course.” He was a gentleman, after all, and she was a lady in distress.

“Nobody uses my name,” she said, folding his handkerchief tidily in half over her knees. “Old retainers will call me Miss Ellie, but they’re few and far between, and it isn’t the same. We’re neighbors. I would be pleased if you and yours would not stand on formality with me.”

Trent had been happy to become Viscount Amherst upon his majority, because it was a step up from what his father typically called him. Now, he dreaded the day he’d be Wilton.

“I will happily use your name under appropriate circumstances,” he replied slowly. “Except, my memory fails me. Your given name is Eleanor?”

She shook her head, stroking his hopelessly wrinkled handkerchief yet more. “Most people think it is, but my mother had a whimsical streak. My given name is Elegy, hence, Ellie.”

“Shall I call you Elegy? The name seems a short removed from ‘eulogy,’ and I can’t think that would be helpful.”

“Ellie.” She beamed at him, expectation in her gaze.

“Trenton,” he replied, with a sense of yielding to fate—or doom. “Trent to my family and friends.” Though not to his wife. To Paula, he’d been unfailingly Amherst.

“I will call you Trent under appropriate circumstances and take my leave of you before I conjure more mortification, in addition to bawling like an orphaned calf and falling asleep like a tipsy dowager.”

Trent drew her to her feet. “I’ve spent my share of time with the bovines and the dowagers, and I can’t recall enjoying the experiences half so much as I’ve enjoyed this time with you.”

“You are kind.” She slipped her arm through his and let him escort her back to the stables. When they arrived, Trent was relieved to see Arthur had been saddled up, Lady Rammel’s groom having been sent the short distance home rather than linger waiting for her at Crossbridge.

He rode along to Deerhaven with her, assisted her to dismount in her own stable yard, and about fainted dead away when she went up on her toes and kissed his cheek in parting. When she pulled away, she smiled up at him, a woman not given to vapors who had only needed a little comfort.

A neighborly kiss then, a widow’s kiss. Nothing more.

He bowed and took his leave, letting Arthur amble back through the wood on a loose rein as Trent tried to put his finger on what had pleased him about the morning’s exchange—because amid all the awkwardness and poor conversational gambits, they’d shared something gratifying, too. Lady Rammel—Ellie—was a toothsome woman with a lovely smile and a quick wit, true, but there was something more.

She’d trusted him. A woman did not cry, much less cat-nap, in the presence of a man she didn’t trust. She’d let Trent in, to her emotions, her motivations, her thoughts. She should trust him, of course, because he was a gentleman, and yet, Trent found it flattering that she did.

Also disturbing as hell.

End of Excerpt

Trenton is available in the following formats:

Grace Burrowes Publishing

April 1, 2014

- Grace’s BookstoreThis is Grace’s

independent

ebook store.

Your purchase can be added to any device. - Barnes & Noble Nook

- Kobo

- Apple Books

- Amazon Kindle

eBook:

Other eBook Purchase Options:

Print:

- Kobo UK

- Booktopia AUS

- Amazon UK

- Amazon Kindle UK

United Kingdom:

Connected Books

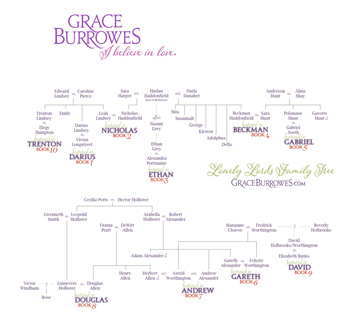

Trenton is Book 10 in the Lonely Lords series. The full series reading order is as follows:

- Book 1: Darius

- Book 2: Nicholas

- Book 3: Ethan

- Book 4: Beckman

- Book 5: Gabriel

- Book 6: Gareth

- Book 7: Andrew

- Book 8: Douglas

- Book 9: David

- Book 10: Trenton

- Book 11: Worth

- Book 12: Hadrian

- Book 13: Ashton

- Book 14: The Duke’s Disaster

- Bundle: The Loneliest Lords

Bonus Material

-

The Lonely Lords Family Tree →

-

Deleted Scene from Trenton →