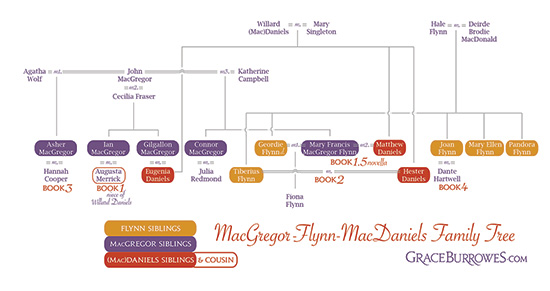

The Bridegroom Wore Plaid

Book 1 in the MacGregor series

In an effort to preserve the family estate, Ian MacGregor, the Earl of Balfour, must marry for money. When a promising match emerges in the form of Genie Daniels, a rich English heiress, Ian begins devising a strategy to woo her. When he meets Genie’s poor cousin Augusta, he discovers a new avenue to Genie’s heart. But after spending time with Augusta and falling for her charms, Ian begins to question whether or not he’s willing to forfeit his heart to save the family name…

Bonus Materials →

Enjoy An Excerpt

CHAPTER ONE

“It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single, reasonably good-looking earl not in possession of a fortune must be in want of a wealthy wife.”

Ian MacGregor repeated Aunt Eulalie’s reasoning under his breath. The words had the ring of old-fashioned commonsense, and yet they somehow made a mockery of such an earl as well.

Possibly of the wife too. As Ian surveyed the duo of tittering, simpering, blond females debarking from the train on the arm of their scowling escort, he sent up a silent prayer that his countess would be neither reluctant nor managing, but other than that, he could not afford—in the most literal sense—to be particular.

His wife could be homely, or she could be fair. She could be a recent graduate from the schoolroom, or a lady past the first blush of youth. She could be shy or boisterous, gorgeous or plain. It mattered not which, provided she was unequivocally, absolutely, and most assuredly rich.

And if Ian MacGregor’s bride was to be well and truly rich, she was also going to be—God help him and all those who depended on him—English.

For the good of his family, his clan, and the lands they held, he’d consider marrying a well-dowered Englishwoman. If that meant his own preferences in a wife—pragmatism, loyalty, kindness, and a sense of humor—went begging, well such was the laird’s lot.

In the privacy of his personal regrets, Ian admitted a lusty nature in a wife and a fondness for a tall, black-haired, green-eyed Scotsman as a husband wouldn’t have gone amiss either. As he waited for his brothers Gilgallon and Connor to maneuver through the throng in the Ballater station yard, Ian tucked that regret away in the vast mental storeroom reserved for such dolorous thoughts.

“I’ll take the tall blond,” Gil muttered with the air of man choosing which lame horse to ride into battle.

“I’m for the little blond, then,” Connor growled, sounding equally resigned.

Ian understood the strategy. His brothers would offer escort to Miss Eugenia Daniels and her younger sister, Hester Daniels, while Ian was to show himself to be the perfect gentleman. His task thus became to offer his arms to the two chaperones who stood quietly off to the side. One was dressed in subdued if fashionable mauve, the other in wrinkled gray with two shawls, one of beige with a black fringe, the other of gray.

Ian moved away from his brothers, pasting a fatuous smile on his face.

“My lord, my ladies, fáilte! Welcome to Aberdeenshire!”

An older man detached himself from the blond females. The fellow sported thick muttonchop whiskers, a prosperous paunch, and the latest fashion in daytime attire. “Willard Daniels, Baron of Altsax and Gribbony.”

The baron bowed slightly, acknowledging Ian’s superior if somewhat tentative rank.

“Balfour, at your service.” Ian shook hands with as much hearty bonhomie as he could muster. “Welcome to you and your family, Baron. If you’ll introduce me to your womenfolk and your son, I’ll make my brothers known to them, and we can be on our way.”

The civilities were observed, while Ian tacitly appraised his prospective countess. The taller blond—Eugenia Daniels—was his marital quarry, and she blushed and stammered her greetings with empty-headed good manners. She did not appear reluctant, which meant he could well end up married to her, provided he could dredge up sufficient charm to woo her.

And he could. Not ten years after the worst famine known to the British Isles, a strong back and a store of charm were about all that was left to him, so by God, he would use both ruthlessly to his family’s advantage.

Connor and Gil comported themselves with similarly counterfeit cheer, though on Con the exercise was not as convincing. Con was happy to go all day without speaking, much less smiling, though Ian knew he, too, understood the desperate nature of their charade.

Daniels made a vague gesture in the direction of the chaperones. “My sister-in-law, Mrs. Julia Redmond. My niece, Augusta Merrick.” He turned away as he said the last, his gaze on the men unloading a mountain of trunks from the train.

Thank God Ian had thought to bring the wagon in addition to the coach. The English did set store by their finery. The baron’s son, Colonel Matthew Daniels, late of Her Majesty’s cavalry, excused himself from the introductions to oversee the transfer of baggage to the wagon.

“Ladies.” Ian winged an arm at each of the older women. “I’ll have you on your way in no time.”

“This is so kind of you,” the shorter woman said, taking his arm. Mrs. Redmond was a pretty thing, petite, with perfect skin, big brown eyes, and rich chestnut curls peeking out from under the brim of a lavender silk cottage bonnet. Ian placed her somewhere just a shade south of thirty. A lovely age on a woman. Con would call it a dally-able age.

Only as Ian offered his other arm to the second woman did he realize she was holding a closed hatbox in one hand and a reticule in the other.

Mrs. Redmond, held out a gloved hand for the hatbox. “Oh, Gus, do give me Ulysses.”

The hatbox emitted a disgruntled yowl.

Ian felt an abrupt yearning for a not-so-wee dram, for now he’d sunk to hosting not just the wealthy English, but their dyspeptic felines as well.

“I will carry my own pet,” the taller lady said—Miss Merrick. A man who was a host for hire had to be good with names. She hunched a little more tightly over her hatbox, as if she feared her cat might be torn from her clutches by force.

“Perhaps you’d allow me to carry your bag, so I might escort you to the coach?” Ian cocked his arm at her again, a slight gesture he’d meant to be gracious.

The lady twisted her head on her neck, not straightening entirely, and peered up at him out of a pair of violet-gentian eyes. That color was completely at variance with her bent posture, her pinched mouth, the unrelieved black of her hair, the wilted gray silk of her old-fashioned coal scuttle bonnet, and even with the expression of impatience in the eyes themselves.

The Almighty had tossed even this cranky besom a bone, but these beautiful eyes in the context of this woman were as much burden as benefit. They insulted the rest of her somehow, mocked her and threw her numerous shortcomings into higher relief.

The two shawls—worn in public, no less—half slipping off her shoulders.

The hem of her gown two inches farther away from the planks of the platform than was fashionable.

The cat yowling its discontent in the hatbox.

The finger poking surreptitiously from the tip of her right glove.

Gazing at those startling eyes, Ian realized that despite her bearing and her attire, Miss Merrick was probably younger than he was, at least chronologically.

“Come, Gussie,” Mrs. Redmond said, reaching around Ian for the reticule. “We’ll hold up the coach, which will make Willard difficult, and I am most anxious to see Lord Balfour’s home.”

“And I am anxious to show it off to you.” Ian offered an encouraging smile, noting out of the corner of his eye that Gil and Con were bundling their charges into the waiting coach. The sky was full of bright, puffy little clouds scudding against an azure canvas, but this was Scotland in high summer, and the weather was bound to change at any minute out of sheer contrariness.

Miss Merrick put her gloved hand on his sleeve—the glove with the frayed finger—and lifted her chin toward the coach.

A true lady then, one who could issue commands without a word. Ian began the stately progress toward the coach necessitated by the lady’s dignified gait, all the while sympathizing with the cat, whose displeasure with his circumstances was made known to the entire surrounds.

Fortunately, Mrs. Redmond was of a sunnier nature.

“It was so good of you to fetch us from the train yourself, my lord,” Mrs. Redmond said. “Eulalie told us you offer the best hospitality in the shire.”

“Aunt Eulalie can be given to overstatement, but I hope not in this case. You are our guests, and Highland custom would allow us to treat you as nothing less than family.”

“Are we in the Highlands?” Miss Merrick asked. “It’s quite chilly.”

Ian resisted glancing at the hills all around them.

“There is no strict legal boundary defining the Highlands, Miss Merrick. I was born and brought up in the mountains to the west, though, so my manners are those of a Highlander. And by custom, Ballater is indeed considered Highland territory. We can get at least a dusting of snow any month of the year.”

Those incongruous, beautiful eyes flicked over him, up, up, and down—to his shoulders, no lower. He tried to label what he saw in her gaze: Contempt, possibly, a little curiosity, some veiled boldness.

Shrewdness, he decided with inward sigh, though he kept his smile in place. She had the sort of noticing, analyzing shrewdness common to the poor relation managing on family charity—Ian recognized it from long acquaintance.

“How did you come to live in Aberdeenshire?” Mrs. Redmond asked as they approached the coach.

An innocent question bringing to mind images of starvation and despair.

“It’s the seat of our earldom. I came of age, and it was time I saw something of the world.” Besides failed potato fields, overgrazed glens, and shabby funerals. He handed the ladies in, which meant for a moment he held the hatbox. His respect for the cat grew, since from the weight of the hatbox, the beast would barely have room to turn around in its pretty little cage.

Ian knew exactly how that felt.

He handed the cat up to the coachman, closed the coach door, and swung up on Hannibal, because his brothers were already in their respective saddles. Up on the box, Donal waited for the riders to go ahead, lest the mounted contingent have to eat an unnecessary helping of summer dust.

And then they were leaving the crowded surrounds of the Ballater train station, leaving the sound of steam belched from the train, the hubbub of greeting and parting in the station yard, the stomping and tail swishing of coach horses impatient—as Ian was impatient—to be away from the noise.

“What can you tell me?” Ian asked his brothers as they slowed their horses to a walk. The coach had fallen hundreds of yards behind, the aging team needing a modest pace on the many inclines on the road to Balfour House.

“The younger daughter, Hester, is harmless, but not stupid,” Connor said. “My guess is she knows she has to wait until the older one is wed before she herself goes on the block. She won’t be a problem.”

“See that she isn’t.”

Connor nodded, no doubt resigned to having to dance and flirt—as best he could—with yet another English miss.

“Gil, what about my prospective bride?”

Gil fiddled with his reins, adjusting the balance of curb and snaffle. “Pretty, which should make married life a little easier, at least during daylight hours.”

“What does that mean?”

Gil’s lips flattened. “She’s… nervous. Anxious, but many women are not pleased to be making long trips by train. I can’t say in five minutes of her company I came to any significant conclusions about Miss Daniels.”

Gil had gotten a generous helping of the family charm along with his blond good looks. If there was more intelligence to gain regarding Miss Daniels, he was the best man to gather it.

Con glowered at nothing in particular. “It was MacDaniels until a few generations ago.”

“It’s Daniels now,” Ian said. “Well, keep your eyes and ears open. The shorter chaperone strikes me as pleasant enough, though those types are easy to underestimate. The taller one is decidedly lacking in cheer.”

Con’s mouth quirked up. “Serves you right.”

“She could be an ally,” Ian said. “If she’s willing to see her cousin matched to a Scottish earldom, then a fat English dowry is that much closer to our dirty, grasping hands.”

Con’s smile disappeared as he glared at his horse’s mane. “There has to be another way.”

“There isn’t.” Gil’s tone was weary. “Thank God that Her Majesty has made all things Scottish fashionable, particularly strutting about the Highlands in summer. The paying guests get us from year to year, from crop to crop and shearing to shearing. We’d be on the boat to Nova Scotia without them. They will not keep Balfour in any sort of repair, though, and they leave us precious little to send along to the others.”

“We’re doing all right,” Ian said. But just all right. Another blight on the crops, a sickness in the flocks, a new tax from London, and all right would not be good enough. As much coin as they sent to their myriad relations in the New World, there was always a need for more.

“We’re waltzing and flirting our lives away,” Con said. “It’s enough to make that boat to Canada look very, very good.”

He’d let his diction lapse: verra, verra guid. As the youngest, Con had come down from the mountains most recently, but it was more than that. This charade took a toll on them all, but on Con worse than Ian or Gil. Con was their horsemaster, a man more comfortable out-of-doors among the beasts than swilling tea in his dress kilt.

“Race you!” Gil drove his heels into his horse’s sides, shooting out from between his brothers like a blond streak. Con thundered after, while Ian held Hannibal back through a series of impatient crow hops and props.

“Settle, you. A fellow of your dignified years has no business disporting like a cocktail lad of three.”

At the sound of Ian’s voice, the gelding ceased his antics. They were both getting too old to caper around for the sheer hell of it, but as Ian watched the coach come lumbering up the hill behind him, he wheeled his horse and shot off after his brothers.

“My goodness, the men here are certainly tall!” Hester offered this observation to the coach at large.

“And… substantial,” Julia concurred, wiggling her eyebrows in an unwidow-like manner. “Verra, verra substantial.”

“Naughty, Aunt, mimicking the locals.” Eugenia was smiling. Not the bored, arch expression Augusta saw on her so often, but a genuine, affectionate smile.

“Sometimes being a saint grows tiresome,” Julia said. “Gus, the Scottish air has put roses in your cheeks. Surely this bodes well for our stay in Aberdeenshire.”

“One need not travel this far from the good air of Oxford to acquire roses in one’s cheeks,” Augusta replied. “I will be surprised if that wretched trip didn’t leave the lot of us with permanent aches in unmentionable locations.”

This remark occasioned much drollery, which Julia abetted shamelessly while Augusta watched the passing countryside. In its craggy majesty and bleakness—the mountains here sported no trees above a certain altitude—the landscape bore a resemblance to the strapping specimens of Scottish manhood who’d met their train.

This trip had not been Augusta’s idea—she’d been dead set against it, in fact—but there was pleasure in spending time with her female cousins. Willard and Matthew, thank the angels, had seen fit to spend this leg of the journey up on the box with the coachman, meaning Augusta could relax just a bit.

Mentally, anyway. The stays biting into her hips and sides made physical relaxation impossible.

“Pretty country,” Genie remarked from her place beside Augusta. “One can see why Her Majesty chose it for her private residence.”

Austere, perhaps. Not pretty. “Attractive in its way, but so is Kent.”

Something passed through Genie’s blue eyes, something that marred the classic English beauty of her features. If Augusta had been forced to name it, she might have called it despair.

And what would such a lovely young lady, the world at her feet after three very successful Seasons, have to despair over?

“You aren’t the one being paraded before every title with pockets to let, Cousin.” Genie turned her head to look out the other window. “I appreciate that you’ve abandoned your rose gardens to chaperone Hester and me, but is the duty really so onerous when all you’ll be doing is walking in Lord Balfour’s woods and dancing with his brothers?”

“Not… onerous, though you know I do not dance.”

“You did.” That from Julia, the traitor. “When you came out you danced quite often, Gussie.”

“Nearly a decade ago, when there was no choice but to dance.”

A little silence fell, while Augusta felt a despair of her own. This was her lot in life now, to kill confidences from her younger cousins, to leave little clouds of awkwardness and disapproval in her conversational wake. But really, for Julia to bring up Augusta’s come-out…

“Did you fancy Lord Balfour, Genie?” Hester put the question quietly. Because Augusta was sitting beside Genie, she saw the girl’s mouth tighten.

“Cousin Augusta doesn’t dance,” Genie said. “I do not seek marriage to a stranger sporting a title. I’m sure Lord Balfour is a very amiable gentleman, but I’m not here to become his countess.”

Her tone consigned all amiable gentlemen to the jungles of darkest Peru.

“Papa mightn’t agree with you.” Hester’s tone bore no malice. “We’re both for titles, Genie. You’ve heard him lecturing Mama about it incessantly.”

“Then you marry the Scottish earl.”

Hester, with characteristic good cheer, appeared to consider the notion. “He’s handsome, if tall.”

“And substantial,” Julia added. “Don’t forget that. I like his eyes.”

“Maybe you should marry him, Aunt,” Hester suggested, lips curving. “I hadn’t noticed his eyes.”

“They’re kind,” Julia said. “I find that very attractive on a man.”

Oh, for pity’s sake. The man’s eyes were green. A startling, emerald green, probably made more striking by his somewhat dark complexion and the thick fringe of dark lashes around them. They were also tired, those eyes. They had a weariness that contrasted subtly with his flashing white teeth, easy grin, and comfortable manners.

“The one with brown hair struck me as serious,” Julia said, egging on her charges. “Maybe he’d be a better match for you, Genie. If he’s the spare, he’ll at least have a courtesy title.”

“Connor has the brown hair,” Hester supplied. “He has the best nose. Gilgallon looks like he laughs more, and I like his blond hair, but his mouth is stubborn. I’d put my money on him as the spare.”

Lord Balfour’s mouth wasn’t stubborn. Augusta frowned, picturing him grinning as he’d swung up on his horse and patted the beast soundly on the neck. His mouth was wide, the lips a trifle full, and on the left side, he had a dimple that flashed when he smiled. With thick, dark hair ruffled by the breeze, he made an attractive picture.

Julia untied her bonnet and set it in her lap. “What constitutes a good nose, Hester?”

“Proud,” Hester said. “Connor has a proud nose, a conqueror’s nose. Not a narrow little whining thing like Richard Comstock-Simms has.”

“My sister has taken up reading noses,” Genie said, her smile back in place now that impending marriage was no longer the subject. “You can make pots of money predicting men’s futures by assessing their noses.”

“We already have pots of money,” Hester retorted. “Which is why Lord Balfour will offer for you. I wouldn’t mind having a Scottish brother-in-law, Genie.”

“Why not a Scottish husband?” Julia asked, deflecting the temper flaring in Genie’s eyes.

“Because Mama will not allow me to marry until Genie is at least engaged. Besides, Genie has had three Seasons, and I’ve had only one.”

Augusta let their combination of banter and bickering wash over her, while she considered Ian MacGregor’s nose.

There was nothing subtle about his nose. Proud applied, but also, perhaps, aristocratic. His nose occupied the middle of his face as a nose ought, but was a little more grand than the standard nose, having the slightest tendency to hook toward the bottom. She knew this because she’d studied the man in profile when he’d offered his arm the second time.

He’d smiled down at her, offering a polite, even friendly smile to a woman whom he could safely dismiss as a nonentity, which was exactly how Augusta intended he view her. Why his willingness to do so should leave her disgruntled, she did not know, nor was she going to waste time pondering it.

The coach rattled along roads likely improved in honor of Her Majesty’s decision to make her private residence at nearby Balmoral. Lord Balfour’s proximity to the royal household had figured prominently in the Daniels’s campaign to have the girls spend much of their summer here in Aberdeenshire.

As if Queen Victoria would pop out from behind a tree and declare herself thrilled to be making the acquaintance of Hester and Eugenia Daniels.

Julia put her bonnet back on twenty minutes later and tied the ribbons beneath her chin. “At long last, our destination. What a lovely, lovely facade.”

Pale gray stone caught bright summer sun, ivy blanketed the northern face, and topiary dragons frolicked along the wings spreading from either side of the main entrance. The house looked comfortable in its setting, secure, affluent, and pretty without being pretentious.

Julia was first to leave the coach, owing to her senior status, but then Augusta motioned for her cousins to leave next. Those oversized, smiling Scotsmen were out there, offering their arms, exuding charm, and generally creating the sort of impression intended to make the ladies forget they were paying a great deal for the privilege of being Lord Balfour’s “guests.”

“Madam?”

She had expected her uncle or perhaps her cousin Matthew to be the last available escort, but Lord Balfour himself loomed in the coach doorway, his hand extended to offer her assistance.

His bare hand. He’d taken off his riding gloves, leaving Augusta to notice that even the backs of his hands were of a darker complexion than an Englishman would feel comfortable exposing socially.

She placed her gloved fingertips on his palm and suffered him to assist her from the coach. All went well as she stepped down, but as luck would have it, her foot landed on a pebble that rolled beneath her weight as she descended.

Leaving her careening into Lord Balfour.

“Steady there.”

She’d pitched ignominiously against his chest, finding him as immovable as a slab of rock.

He smelled better than a rock, though. Leaning against him, Augusta took one half breath to find her balance, enough for her nose to gather the scents of soap, lavender, and something fresh and spicy—heather?—underlain with a hint of horse.

Good smells, clean and bracing. She straightened lest he think her daft. “My thanks, your lordship.”

“Surely Balfour will do? It’s summertime, and we’re far, far from London, Miss Merrick.”

She nodded noncommittally. Calling the man by his title little more than an hour after meeting him was not something Miss Augusta Merrick should be comfortable doing, regardless of the season. She had to like him for offering, though. It suggested some of the warmth in those smiles he tossed around so carelessly might be real.

He put her hand on his arm and patted her knuckles. “I’ll have my sister, Mary Frances, show you to your rooms. We keep a country schedule unless our guests request otherwise. It leaves hours of the gloaming to relax and enjoy ourselves.”

Gloaming. A soft, northern word. He caressed it a little with the burr in his voice.

“I shall retire early and take a tray in my room,” Augusta said. “Train travel does not agree with me.” Let his lordship turn that charm on Genie, where all and sundry knew it was intended to focus.

“We’ll miss your company at table.” He bowed as they gained the front terrace. “And here is Mary Fran, who will be wroth with you if you do not allow her to see to your every comfort.”

Mary Fran, more properly Lady Mary Frances—she was an earl’s daughter, for pity’s sake—was an imposing redhead with the same facile smile as her oldest brother. She collected the ladies with an air of brisk friendliness, and soon had them bustled into their rooms, maids clucking and fussing with an informality that would not have passed muster at all back in the South.

Augusta’s room was done in the current Highland vogue—curtains, bed hangings, carpet, and even wallpaper sported either a green, black, and white plaid, or echoed the hues of the plaid. As a whole, the room was a little dizzying.

“Is all the staff so… familiar?” Augusta asked her maid.

“Familiar, mum?”

“Friendly?”

The girl’s freckled face split into a wide grin. “We’re to treat you like family, laird’s rules. Is there anything else I can do for ye?”

Augusta shook her head and waited while the girl bobbed a curtsy then stopped by the door to check the level of the water in a bouquet of red roses.

And then Augusta was blessedly, finally, at long last, and completely alone.

Wherever Ian looked for Mary Fran—the kitchen, the formal dining room, the pantries, the larder—the servants reported she’d just gone off to some other location, they knew not exactly where.

And though Ian paid them some of the best wages in the shire, he did not fool himself: If the staff was intent on abetting Mary Fran, then she’d elude capture easily, despite her laird, earl, and brother’s pressing need to speak with her.

A flash of red braids and quick, light tread on the footmen’s stairs suggested possible hope. Ian lit up the stairs, two at a time.

“Fiona!” A door banged on the next flight up. “Fiona Ursula MacGregor!”

Silence, meaning the child—who generally knew exactly where her mother had gotten off to—was intent on disregard for authority as well. Ian could expect as much—she was Scottish, a MacGregor, and Mary Fran’s own daughter.

He burst through the door on the upper lands, lungs heaving, ready to bellow the rafters down in search of the child, only to stop short.

“Your lordship.”

His brain was caught unawares, and where the friendly good manners of a charming host ought to be, what his mind came up with was: The one with the pretty, anxious eyes.

“Miss Merrick.” Though not the Miss Merrick he’d met at the train station, or even the Miss Merrick he’d escorted from the coach. This Miss Merrick was clothed in a robe the exact shade between red and purple, a regal, substantial hue that flattered her black hair and perfect skin. She looked curiously luscious, with her hair piled on her head in a soft topknot, and her spectacles perched on her nose.

“I confess, my lord, to having lost my way.” Her smile was more self-conscious than worried. “I was looking for the bathing chamber.”

And while another woman might have been mortified to be caught wandering the hall in a robe, Ian suspected Miss Merrick was more troubled by the loss of her bearings.

He offered her his arm—she was clothed from neck to ankles, for God’s sake, and the house was swarming with people. “It’s easy to get turned about in this house. When I was a boy visiting my grandfather, I delighted in discovering new rooms and hidden stairways.”

And now he was hard put not to resent the entire property.

“Did you also delight in your first experience with train travel? Boys do, I’m told.”

Boys were likely a species of noisy, dirty savage to her. “I take it train travel does not appeal to you?”

When he expected her to rap out some sniffy answer, she looked thoughtful. “I enjoy the sense of mobility, of being able to flee my surrounds for a bit of coin. Having come hundreds of miles though, I find I want nothing so much as the solitude, stillness, and fragrance of a hot bath.”

Interesting, that she did not profess a desire for her home. “You’re in luck then, because we’ve a monstrous roof cistern, and the old chimneys, stairwells, and priest holes were such that installing some water closets wasn’t too much work.”

Though it had been expensive. Holy God, had it been expensive. Only Mary Fran’s threat to lead a mutiny—from laundry, to kitchens, to gardens—had seen the renovations done.

“Who is this? He looks like a younger version of you.”

She’d paused before another extravagance, though this one, Ian was dearly glad for. “That fellow is my older brother, Asher, just before he took ship for Canada.”

“A solemn young man, though quite comely.”

Solemn? They’d been reeling from the effects of the potato blight, reeling from Mary Fran’s scandal with the wretched Captain His Bloody English Lordship Flynn, and reeling from Grandfather’s inchoate decline.

“He had much to be solemn about.” And the New World had given him only more to be solemn about. “The bathing chamber is this way.”

She did not immediately move away from the painting, but stood for another moment, studying a portrait of a young man in Highland attire—not the full regalia; Asher had balked at that notion. Asher had been gaunt, serious to a fault, and proud. Ian hoped the pride at least remained to his brother.

“You have much to be solemn about too,” she remarked when she at last deigned to continue their progress.

Ian mustered a smile. “I have much to take pleasure in as well. I’ve acquired neighbors most fortuitously, we own one of the prettiest patches of ground in God’s creation, and my family enjoys good health.”

“You own it.”

Shrewd and noticing—not an endearing combination in a female.

“I am Scottish, Miss Merrick. Everything I do, I do in the name of my family.” Even finding lost spinsters and guiding them on their way. “Your bathing chamber.”

Ian peeked in and saw that soap, towels, and all the other expensive items Mary Fran claimed were necessary for a lady’s bath had been laid out.

“Has anyone shown you how to work the taps?”

“No.”

And from the look on her face, Miss Augusta Merrick would perish of excessive train travel before she’d ask.

“It’s not complicated.” Ian moved into the marble temple to cleanliness and refined English sensibilities and felt Miss Merrick mincing along behind him. “The one on the right is the cold, the one of the left, hot. You start with cold because the boiler can be cranky, and…”

He trailed off, turning both taps only to find someone hadn’t opened the upper valves. In the small confines of the water closet, he had to reach over Miss Merrick’s head—her hair bore the scent of lemon verbena and coal smoke—to open the feeder taps.

The next few moments happened in a series of impressions.

First came the sensation of the door thwacking into Ian from behind. A stout blow more unexpected than painful, but enough to make him stumble forward.

Then, Fiona’s voice, muttering the Gaelic equivalent of “Beg pardon!” followed by a patter of retreating footsteps.

And then, in Ian’s male brain, the woman with the pretty, anxious eyes became the woman who was soft, lush, and still beneath Ian’s much greater weight.

She didn’t push him away. She didn’t even touch him. The sole indication that his weight was any imposition as he flattened her to the wall, that the impropriety of the moment was any imposition, was her closed eyes.

The final impression threatened to part Ian from his reason: her breasts, heaving against his chest. In preparation for her bath, she’d left off her stays, and the feminine abundance pressed against Ian ambushed his wits.

Shrewd, noticing, and astoundingly well endowed.

When he wanted to press closer, Ian pushed himself away with one hand on the wall and made sure both feeder taps were open. “I do beg your pardon, Miss Merrick.”

“A mishap only. I stumbled upon leaving the coach.”

She would recall that, while Ian had thought nothing of it. His damned male parts were thinking at a great rate now, and all because…

He wasn’t sure why, though lengthy deprivation might have something to do with his reaction—and pretty eyes.

“The valves are open, but mind the hot water.”

She nodded, and Ian got the hell out of there before he said something even more stupid.

CHAPTER TWO

Willard Daniels watched his firstborn son and heir put an empty glass back on the tray where the decanter—now considerably less full than it had been an hour ago—sat winking in the early evening sunshine.

The boy had graceful hands, which was no compliment. Soldiering was supposed to knock the fancy out of a man, but five years in the light cavalry hadn’t quite gotten rid of a certain elegance—fussiness, more like—in the next Baron of Altsax… and Gribbony.

Which was why the summer’s real objective was something Willard would keep to himself. Matthew had an inconveniently generous dollop of scruples rattling around with all the logic and military strategy in his handsome head. It ruined him, like the red highlights in his blond hair, the slight air of diffidence in his mannerisms, the tendency to silence and distance when a peer of the realm sought and was entitled to hearty assurances from his own son.

Disappointment, Altsax had long ago learned to live with, but failure was out of the question. Before Genie or Hester married that buffoon of an earl, before they married anybody, the problem of their aging and awkward cousin was going to be resolved—permanently—lest the Daniels’s family finances and social standing continue to be threatened by Augusta Merrick’s very existence. She’d turned down the only other possible solution—marriage to Matthew, offered half in jest—though seeing how the pair of them had matured, Altsax had to be grateful. Even his brooding disappointment of a son deserved better than that wretched woman, cousin or not.

Such musings were enough to inspire a man to drain the remaining whisky from the decanter.

To be drunk at dinner would be the height of bad form the first night under the earl’s roof, but then, dinner wasn’t going to be for at least an hour. Willard reached for the decanter and offered a private though quite sincere toast to the success of his own schemes.

One of the blessings of entertaining wealthy English aristocracy for weeks on end was that Ian could feed his own household well. For a few months of summer and early fall, there were frequent servings of good Aberdeen Angus beef, the occasional lamb, roasted cuts of pork, chicken too young to be anything but tender, and—reason enough to thank God—not a hint of mutton.

Though there had been many times in Ian’s life when even a thin mutton stew would have been a fair trade for his soul.

Perhaps it had been a fair trade, which was why he was rubbing elbows in evening finery—the kilted version, and bedamned to English fashion—with the half-drunk baron, his tight-lipped son, and his determinedly cheerful womenfolk.

Save the spinster. She at least had the sense to keep to her rooms, where she no doubt was feeding portions of beef to her cat.

The baron rose to his feet a little unsteadily and directed a questioning glance to Ian. “The ladies having departed for their tea and gossip, shall we to the decanter?”

“Of course.” But Ian saw Connor eyeing the food uneaten on the Baron’s plate. More for the kirk in town, though if they knew it was food served to an Englishman, likely even the wretched poor of Aberdeenshire would turn their noses up at it.

“This is first-rate drink,” Matthew Daniels said when all five men were lounging around the library. “Have you ever considered exporting it?”

“Now that’s an interesting proposition,” Connor replied, sparing Ian the trouble. “There is a market for decent whisky, but there’s also a heavy tax imposed, usually at both ends…”

Daniels the Younger launched into a surprisingly intelligent debate with Con and Gil about the risks and rewards of exporting whisky, while the Baron—drink in hand—sidled over to where Ian stood by the window.

“That boy.” The baron expelled a heavily fumed breath. “Talking trade after dinner with the locals. I wash my hands of him.” He turned a long-suffering gaze on his drink, drained the contents, then set the empty glass on the windowsill with a little bang.

“Shall I refresh your drink, Baron?”

“Yes, b’gad. Traveling leaves a man parched, particularly with all them damned, plaguey females. Speaking of which?”

Ian glanced at his guest while he poured a half tumbler of whisky for the baron. He’d chosen the decanter kept farther back along the sideboard, the one reserved for sots who would not be offended by a younger brew. The container itself was fancy and kept just as meticulously dusted as its confreres, but Ian would not have served the contents to Mary Fran’s prize sows.

“This is a special batch,” Ian said, which was true. “Not for everyday consumption. I’d go slowly.”

“Must say”—the baron took a hefty swallow—“for a Scot, you know how to treat your custom.”

“My guests,” Ian corrected gently.

The baron lifted his glass for another sip then turned to face the window. “As I was saying, about the ladies.”

Was business to be broached this soon? A part of Ian was relieved to think the Misses Daniels’s father was so determined to see them settled; another part of him was appalled at the man’s lack of couth. Not under Ian’s roof twelve hours, and already, before it was even apparent Ian would suit his daughter, Altsax was opening negotiations.

“About the ladies?” Ian drawled, joining the baron at the window. Behind them, the younger men had escalated the discussion of whisky exportation into a round of “You damned English/You bloody Scots,” which was great good fun, provided nobody started pounding on anybody indoors.

Mary Fran frowned mightily on broken furniture.

Ian watched as, out on the terrace, Mary Fran started laughing at something Mrs. Redmond had said.

The baron leaned closer, his breath enough to knock a grown man on his arse.

“Just how widowed is your sister, Balfour? She’s a toothsome wench, if a man isn’t put off by all that red hair. And widows tend to be grateful and enthusiastic, y’know what I mean?”

And by greatest bad luck, the baron had spoken in the over-loud confidences of a drunk, his comment falling into one of those peculiar lulls in the other conversation that ensured even the footman at the library door had heard him.

Ian glanced over at his brothers, seeing Con’s lips thinning and Gil’s hand already on Con’s arm.

The insult to Mary Fran had been plain enough that Matthew Daniels’s expression had gone from almost genial to the blank, offended mask at which the English excelled, and everybody in the room was looking at Ian.

The baron wiggled his eyebrows and elbowed Ian in the ribs. “Well?”

Morning came blessedly, beautifully early during a Scottish summer, just as sunset came only gradually and late.

This allowed a man playing host to a group of silly English to get in a few hours of meaningful work before appearing in his finery at breakfast. It also allowed him to stay up late tending to correspondence, and to grab what sleep he needed during the brief darkness.

And it permitted him a solitary ride just as the sun was cresting the horizon, a little time to enjoy the natural beauty of dawn in one of the prettiest places on earth, when he’d otherwise brood about the need to ignore slights to his sister from half-inebriated guests.

Ian had scrabbled for some patience and signaled Daniels to get his dear papa up to bed, though the thought of the Baron as a father-in-law was nauseating.

Each year it felt a little more like this was what Ian’s life would be: scrabbling for patience, scrabbling to keep up appearances, scrabbling to make ends meet, scrabbling to keep what was left of his branch of the clan together, scrabbling to come up with yet another scheme to wrest coin from some new source for the upkeep of the hall and its inhabitants, scrabbling to hold onto hope that Asher would come home.

He should be introduced as the Earl of Scrabbling.

Soon, in support of these burdens, he’d acquire a countess. Even as the Balfour spare, Ian had accepted he’d eventually marry, and marriage to a practical Scotswoman willing to shoulder some of Ian’s burden would have been lovely. Women like Mary Fran understood hard work, sacrifice, and by God, they understood loyalty.

Even that comfort was to be denied him. Eugenia Daniels was pretty enough, but only in a pale, blond, English way. A night in Ian’s bed would likely break her in two and leave her crying for her mother—assuming he could muster any enthusiasm for her intimate company.

Ian’s morose thoughts were interrupted by a lone figure emerging from the shadows at the back of the house. A woman…

He watched the figure striding confidently along the path into the gardens. She was tall, with a long, glossy black braid hanging down the middle of her back. The end of the plait danced in counterpoint to her walk, swinging up rhythmically with each footfall.

Bloody damn. He recognized the beige shawl with the black fringe and nudged Hannibal into a trot.

“Good morning, Miss Merrick.”

She stopped abruptly, her back to him, while Ian dismounted and stuffed his riding gloves into his pockets. He tied up his reins and gave Hannibal a gentle slap on the quarters.

“He won’t wander off?” She’d turned, the shawl clutched around her shoulders.

“He’s Scottish bred. He’ll wander directly to the nearest ration of oats.” Ian offered a smile because the lady looked flustered. “Come, Miss Merrick, and we’ll walk. The gardens show to advantage in morning light.”

Her eyes flicked to the back of house, and Ian felt a sinking sensation in his chest, which by now he should be adept at ignoring. It was one thing to stumble across him in a back corridor, but she didn’t want to be seen walking with him so early in the day, perhaps not at any point in the day.

He took pity on her—she was a lady and not responsible for the prejudices of her sheltered upbringing. “If we take this path to the left, we will not be seen.”

Her chin came up, those disconcerting gentian eyes meeting his gaze. “It isn’t what you think, my lord.”

It never was with proper English ladies.

“What do I think?” He took her hand—devoid of gloves—and placed it on his arm, feeling a spark of—something, something that wasn’t entirely gentlemanly—in doing so.

“You think I am reluctant to be seen in company with a single gentleman at an improper hour out-of-doors.”

Only the English could make a gorgeous, rural dawn improper. “Early morning is the best part of the day,” he said. “It’s the only part of the day we haven’t already mucked up with our fretting and strutting and carrying on.”

“Yes.” She stopped and peered up at him, an odd moment. She looked so long and so thoroughly, it took Ian a moment to realize, without her spectacles, she might have difficulty seeing. “That’s why I was out, because it’s too pretty to stay shut up in that room with Ulysses. But what you think…”

It was his turn to peer at her, until manners saved him and he turned her by the arm to begin their walk. He got her behind the tall privet hedge, where they’d have some privacy, and felt her relax marginally beside him.

“I have a certain place in the family,” she said, slipping her arm free of his to take a seat on a wooden bench. “Won’t you sit for a minute?”

Now that they were private, she wanted to sit with him?

But she clearly did. Her expression was so earnest, her violet eyes solemnly entreating him to spend a little time with her, probably to assuage her lady’s conscience.

Ian sat a proper distance away from her, despite the devilish temptation to rattle her by sitting too close.

“Thank you.” She let the shawl drape down to her elbows. “I am mindful, Lord Balfour, that you are considering a match with my cousin.”

“I am expected to marry,” he said carefully, because the mind of woman was a labyrinthine mystery, and this woman could queer his only shot at the Daniels’s dowry.

She nodded once. “Of course you must take a wife, but Eugenia is hesitant to marry anybody. She’s had three Seasons and any number of offers, but her mama is determined she should have a title.”

Ian knew this much, so he kept his silence.

“Genie is young and has odd, modern notions that marriage ought not to serve material purposes. Either that, or her parents’ example has disheartened her regard for marriage generally.” Miss Merrick’s cheeks colored slightly at these admissions.

“May I be blunt?” Because he did not have all morning to exchange civilities with this woman, even if it did appear the Lord had given her a wealth of shining dark hair to go with her pretty, solemn eyes.

“Please. Most people are blunt with me, and I’m not as easy to shock as you might think.”

Oh, right. Of course not.

“Is it marriage your cousin objects to, or the intimacies expected of a wife?”

Her eyebrows rose, but only that. Ian waited on her answer, because a marriage in name only would be a relief of a sort—also a bitter curse.

“Now that you raise the possibility,” the lady said slowly, “I suspect there is aversion to the… intimacies, though both Julia and I have tried to reassure Genie that her fears are groundless.”

“I gather, then, that you do not oppose the match?” And what would a spinster know of those intimacies?

“I cannot oppose a good match for my cousin. You see, your lordship, I am living the alternative to a congenial marriage. I have given Genie my word I will not maneuver her into a situation where her choices are taken from her, but if you and she were respectfully disposed toward each other, in my heart I would have to support the match. You would be kind to her?”

Kindness? What place had kindness in a discussion of money and security for his family and their kin? But looking into a pair of earnest violet eyes, Ian realized he had something in common with this woman.

She was lonely and alone even among her family. She was more alone with family around her, in fact. He reached over and lifted her shawl around her shoulders.

“You’ll take cold in the morning damp.”

Still, she watched him, waiting on his answer.

“I know little of kindness, Miss Merrick, but I understand honor, and I understand that a smile and an encouraging word can foster good relations when silence and criticism do not. Women are deserving of every consideration. I would show my wife nothing less than perfect courtesy.”

She shuddered, likely not at the brisk morning air. “Courtesy can be the unkindest cut, you know. My uncle excels at such courtesy, my aunt as well.”

So he had this in common with her too—a distaste for Willard Daniels.

“Marriage would spare you their dubious courtesy, so why aren’t you married, then?” Without her hair scraped into a bun or that pinchy expression to her mouth, without her glasses, she wasn’t at all bad looking, nor was she as old as Ian had first thought. And those eyes…

“I had a Season.” She said this the way an old soldier might talk about besting a worthy enemy on a faraway battlefield, her eyes going soft and distant. “I had my come-out, I had a Season like every girl dreams of, but then my parents died, Papa then Mama, and the mourning took two years. By the time I was ready to resume my place in Society, my situation had changed.”

He let a silence stretch—not uncomfortable, with her sitting beside him—and moved puzzle pieces around in his mind.

Her situation had changed because when her mourning was over, her cousin Genie had been preparing to emerge from the schoolroom, and it was Genie’s papa, not Miss Merrick’s grandfather, who would control the purse strings, and both English and Scottish baronial titles.

“Your uncle refused to dower you.”

She looked down at her hands where they rested in her lap, her shawl again slipping to her elbows. “Perhaps.”

Ian followed the line of her gaze, noting that from beneath the damp hem of her nondescript walking dress, he could see the first two naked toes of her right foot.

A lady of hidden daring, then. He stifled a smile and brought his attention back to the conversation. “Miss Merrick. I have a sister, I have a young niece, and more cousins than you can count. I understand that family can be a trial.”

She nodded, eyes still downcast. “Uncle explained he would have the support of me for all my years, and then he did the math. Several Seasons plus a dowry would be a much greater burden on the barony than were I to accept the alternative, and he did give me the option of marriage to my cousin Matthew.”

Interesting tactic on the baron’s part. Ian stored that insight away for further consideration.

“You were not inclined, Miss Merrick? Her Majesty married a cousin, and the union appears to be prospering.”

“She married a cousin she’d never met until courting was in the air. Matthew was like a brother to me growing up, and I could not do that to him, not even for the promise of children and the eventual title of baroness. So I am a poor relation, and larking about half clad in the morning dew does not comport with my role.”

A minor puzzle formed in Ian’s mind: Children and a title were probably the greatest inducements that could have been dangled before her, a gently bred English lady—and she’d turned them down.

“I understand costumes and roles.” He reached over to pull her shawl up around her shoulders yet again, as she seemed determined to let the thing fall where it may. “I’m disguised as an earl, for example, one who’s pleased to open his home to guests each summer when Her Majesty is in residence next door.”

It was an admission. Not one he’d planned to make, but her smile told him she was pleased to accept it.

“You should not judge yourself for taking Uncle’s coin. He’s a trial on a good day, and he’ll dine out on his summer with the Queen for years.”

“And I’m not really an earl, not yet.” He glanced over to make sure she was paying attention, because this truth was one he did not want hidden. “My half brother, Asher, holds the title, but he’s been missing for almost seven years. We’ve started the proceedings for having him declared legally dead, though at the last moment, I expect him to come strolling off a boat, thanking me for my impersonation of him.”

“Uncle knows this. He’s been spying on you for a bit.”

A confidence for a confidence. Miss Merrick rose a notch in Ian’s estimation.

“Has he now? I suppose that’s to be expected.” And Miss Merrick no doubt feared such an uncle would also spy on his niece. “Come with me, and I’ll show you where you can pick up a trail in the woods that will allow you all the solitude you want, most of it within shouting distance of the house and stables.”

“Another time perhaps.” She rose, her expression genuinely rueful. “If I’m seen gadding about with my hair in disarray and my hems getting soaked, there will be questions at breakfast. You won’t tattle?”

This was important to her, her eyes suggesting it was tantamount to a matter of safety and peace of mind.

He got to his feet. “A gentleman would never reveal a lady’s confidences, Miss Merrick. Never.”

She looked relieved, and then indecisive, as if she might say more or take his hand to solemnize the exchange. But she turned, pulled the ugly shawl up, skittered away, then darted back to his side.

Ian had no warning. She rested a hand on his chest then went up on her toes and grazed her lips against his cheek. He got a fleeting impression of warmth and softness and a little whiff of spring flowers before he had the presence of mind to steady her by the elbows. For a procession of instants, she remained next to him, a woman who likely permitted herself no allies and no affection. Ian’s hands slid from her elbows to her waist, sharing an embrace that was as comforting as it was unexpected.

She was not prim, fussy, and prejudiced. She was shy, lonely, and uncertain.

Also brave.

It was a sweet moment, and just as Ian might have stepped back and bowed over her hand, she whirled away.

In a flurry of tan shawl and bare feet, she scampered off, reminding Ian of a doe startled at her quiet grazing, then fleeing into the safety of the surrounding shadows.

The Earl of Balfour was a more complicated man than Augusta had wanted to credit. She pondered this realization while she exchanged her old walking dress for a day dress of almost the same sorry vintage.

Her first impression of him was that he had decent manners, a genial disposition, and—like many of his peers—did not suffer from excesses of introspection. And she’d thought him… big. Physically, big. Tall, broad through the shoulders, solid in the chest, and whether he wore riding attire or the kilts he seemed so fond of, she could see his legs had as much muscle as the rest of him.

Big, fit, and handsome in a tall, black-haired, green-eyed Scottish way.

And then he’d caught her in all her ridiculous glory this morning, giving in to the impulse to feel the wet grass on her feet, to sniff a fat, bloodred rose sporting morning dew, to allow the morning sun to kiss her bare cheeks.

Things she could do in exile in Oxfordshire but had missed terribly during these weeks when she’d again been in the company of her family.

The earl hadn’t remarked her behavior. He’d been courteous but honest, gruffly honest. She’d liked the honesty and had tried to convey her approval by returning his candor in full measure. The more serious earl, the man who bluntly broached topics like marriage and Genie’s hesitance to become his countess, was a more appealing fellow than the easygoing host.

Too appealing, if her impulsive little buss to his cheek was any indication. What had she been thinking, to presume on his person that way? And in what tidy little compartment of proper thought and behavior was she going to stash the memory of their embrace?

He’d been oddly gracious. The first time he’d tucked her shawl up, Augusta hadn’t known quite what he was about and had nearly flinched away. The second time, she’d found it… intriguing.

Not quite endearing. Endearing was the grave look in his emerald green eyes when he informed her he was not yet officially the earl. Augusta had heard her aunt and uncle discussing this at tiresome length, with Uncle pointing out the man was at the very least an earl’s heir, complete with courtesy title, and likely to be the earl in the next year.

So Aunt had pleaded for a yearlong engagement, and Uncle had started ranting.

Augusta gave her hair a repinning after she’d changed into morning attire. She hadn’t intended to go to breakfast, but the day had had a promising start. The more she got to know Lord Balfour, the more Augusta was convinced he could make Genie a very decent husband after all.

The man apparently intended to begin his campaign with the morning meal. Augusta watched from her place opposite the laden sideboard as he managed to arrive at the breakfast parlor at the exact same moment as Genie.

“Good morning, Miss Daniels and Miss Hester,” he said from the doorway “You both have the radiant appearance of women who’ve enjoyed a fine night’s rest.”

“I was asleep before my head hit the pillow,” Hester said, sailing into the room. “My goodness, this is breakfast in Scotland? I was expecting bannocks with my tea. Genie, do come along lest I eat everything I see.”

“Miss Daniels?” The earl waited politely for Genie to pass before him into the room. “May I fix you a plate?”

“Thank you, but I don’t typically enjoy much of an appetite first thing in the day.” Genie cast Augusta a look probably intended to convey a plea for help—which would not be forthcoming. For the earl to see to a lady guest’s plate was perfectly proper and even considerate.

“The scones are very good,” he said, quirking an eyebrow. “I’m thinking you’d best have a couple lest Miss Hester remove them as an option.”

“Smart man.” Hester plucked a pastry from the tray as she cruised along the buffet. “And you’ll want to watch the butter, because Augusta slathers it on like she’s trying to keep every bossy cow in the shire secure in its employment.”

“We have a lot of cows here in Aberdeen. Good morning, Miss Merrick. I hope you slept well?”

And there was not a hint of innuendo, humor, or anything in his inflection or his expression. Such an accomplished actor would likely lie convincingly as well, which was a disconcerting realization.

“I did sleep soundly. I kept the terrace door open to humor my cat. I think the fresh air agreed with us both.”

“Imagine that—a feline being pleased with something. I don’t know as I’ve seen the like.” He turned back to Genie, who was hovering by the array of food. “Some bacon, ma’am? A bit of ham?”

“Just the scone for now, thank you, my lord.”

“None of that. You’re my guest. Balfour will do, and I shall call you Miss Genie, hmm?” He set her plate on the table and waited to hold her chair, while Genie shot Augusta an even more panicked look.

“Of course you shall call her Miss Genie,” Augusta said, reaching for the teapot. “Formalities at breakfast do not aid digestion.”

She could not endorse lingering behind a privet hedge with a handsome earl as an aid to digestion either.

“Hear, hear.” Hester waved her fork in a little circle to emphasize her agreement. “I could do with a spot of that tea, Cousin. I’ve an entire tray of scones to wash down.”

“Save some for me,” the earl said. “If my brothers descend… speak of the devils.”

The earl started filling his plate while Connor and Gilgallon came into the breakfast parlor, boots thumping on the polished wood floor.

“Morning, all,” Gilgallon said, his blond good looks showing to advantage in riding attire. “Ladies, you each look to be blooming. This tells us Ian hasn’t attempted any polite conversation yet.”

“Don’t let him spoil your appetite,” the earl stage-whispered to Genie as he took the place at her elbow. “Scots are nothing if not tenacious, and I’m determined to beat some manners into him.”

“I’d help,” Connor said, “but I think beating manners into a fellow something of a contradiction. Ian, I am going to tattle to Mary Fran that you’ve left us only a half-dozen scones, and you, Miss Hester, will be my corroborating witness.”

Augusta watched as the earl occasionally dropped his voice to whisper something to Genie, who gradually relaxed under the onslaught of his charm. He topped up her teacup, passed her the cream and sugar, sliced a ripe peach—Her Majesty was said to adore a peach at the conclusion of her evening meal—and put most of it on her plate.

It was breakfast with a side helping of subtle, well-disguised overtures from a man interested in gaining a lady’s notice. By the third cup of tea, Genie reached for a bite of peach from the earl’s plate then froze with her hand in midair.

“I beg your pardon, my lord.” Her hand returned to her lap, while color rose in her cheeks. “I should not presume upon your very breakfast.”

Gilgallon reached across the table and plucked the slice of fruit from his brother’s plate. “Why not? If you don’t, I will, and then there’s Con, and Mary Fran, and…”

“What about Mary Fran?” The earl’s sister posed her question from the door then headed directly for the buffet. “And the truth, Gilgallon Concannon MacGregor, or I’ll skelp yer bum but good.”

Julia spoke up for the first time. “You’ll do what?”

“She’ll spank him,” Connor supplied, for Gilgallon was munching his peach, or the earl’s peach. “Again. Motherhood has made Mary Fran a dab hand with a spanking.”

“Quit braggin’ on me, ye daft, glaikit mon,” Mary Frances said, bringing a full plate to the table.

A few more minutes into the general banter, Augusta noticed the earl leaning over to offer Genie another one of his teasing asides, but Genie kept her gaze on her teacup, apparently wise to the man’s tricks. Balfour left off his wooing, for that’s what it was, when Matthew joined the assemblage.

Matthew, who might have been Augusta’s… husband.

She regarded her cousin with as much dispassion as she could muster over hot, buttery scones and strong breakfast tea.

He was handsome, tall, lithe, and where she had gotten some ancestor’s Celtic black hair, Matthew had been spared such a fate and sported blond hair going reddish at the temples. He’d been spared the peculiar eyes too, his being a perfectly circumspect shade of blue.

She tried to consider him objectively—they were both presently unwed—but the idea of bearing his children left her… disturbed. Cousins could marry legally, and royal cousins frequently did.

Matthew had been the one to teach her how to tie her boots, the older boy who’d shown her how to make a fist—thumb outside—and instructed her about where exactly a female might knee a bothersome fellow to allow her time to flee to safety. These were not memories conducive to marital inclinations. Not years ago and not now.

And Matthew had grown so serious. The change had started before he’d joined the cavalry, and Augusta regretted it—for his sake and for hers.

“Good morning, Cousin.” Matthew took a seat beside her as he spoke. “The teapot, if it wouldn’t be too much trouble?”

She obliged, pouring for him in silence. Several seats up the table, Gilgallon was now appropriating his sister’s bacon and getting his tanned wrist slapped for it.

“Such violence in an earl’s daughter,” Connor chided, taking a sip of Gil’s tea. “And I’ve diagnosed Gil’s problem. He fails to sweeten his tea, which cannot be good for his disposition.”

“My disposition would benefit from a ride directly after breakfast,” Gil said, ignoring his brother’s larceny. “And I would sweeten my tea, but you lot have plundered the sugar bowl.”

“Perhaps the ladies would like to join you on your ride,” the earl suggested. He lounged at his end of the table, lord of all he surveyed, a smile lighting his eyes.

How different this breakfast was among Scottish strangers from all the breakfasts Augusta had shared with her relations—and the breakfasts she’d shared with nobody save her cat.

“I would enjoy a tour of the estate,” Genie said, pinning a nigh-desperate gaze on Gil. “A tame mount would be best, though.”

“We’ll make it a foursome if the younger Mr. MacGregor will come along,” Hester chimed in, smiling at Connor. “Aunt, perhaps you’d like to join us as well?”

Julia appeared to consider this offer as she peered at her tea. “It has been ages since I’ve ridden. Augusta, will you join us so I won’t be the only one left to amble along on an aged pony?”

Augusta was tempted. Oh, how she was tempted. But Uncle chose that moment to join them, and for her to be riding about with the young ladies when Julia was on hand to so do might be getting above her station.

“I’ll leave the girls to your watchful eye,” Augusta said. “Perhaps I’ll ride some other day.”

Three seats up, the Baron folded down his newspaper and frowned at the sugar bowl. “We’re to tour the estate? Can’t say as I approve of riding after a full meal. You girls mind your aunt, and when you’re done, be sure to send along notes to your mama, else she’ll be pestering me to death for word of your doings. Pass the teapot, Gussie.”

Augusta did as bid. She always did as her uncle bid her, but she also noticed the earl was not making noises to join the riding expedition.

Prudent of him, to only advance his cause so far then leave Genie some time to regain her balance. It wasn’t as if his own brothers were going to undermine his prospects with Genie, were they?

CHAPTER THREE

Ian counted breakfast a limited success, in part because Gil had been canny enough to suggest an outing for the ladies that Ian could easily decline.

Always leave your opponent a graceful out. Grandfather’s words echoed in Ian’s mind, though Ian wondered how a battle-hardened soldier had applied those words in a life-or-death struggle. They had merit in a wooing, or whatever Ian was engaged in with Miss Daniels.

Miss Genie. Who’d looked only relieved when Miss Merrick had requested Ian’s company on a tour of the library.

“Have you many novels in your library?”

Miss Merrick voiced her question tentatively, as if novels were some kind of pornography. Perhaps in her lexicon they were.

“Mary Fran claims we’re to stock them for guests. Connor says any Scots household worth its salt has to have a full complement of old Sir Walter. Gil’s excuse is that we keep them on hand for Mary Fran, while I admit to reading occasionally purely for recreation.”

As she walked beside him along the rows of shelves, her eyes grew wide. “You admit such a thing?”

“There are advantages to being head of the household.” He refrained from giving her a conspiratorial wink lest the poor thing expire from an excess of innuendo, but there was pleasure in showing her what remained of the family library. She ran a single, tentative finger down the spine of each volume he pointed out, her touch slow and reverent, a kind of literary caress.

“Books were my salvation,” she said as they paused by the old atlas spread on a gate-legged table. “When Papa died and then Mother died so soon after, I was quite alone. Proper mourning leaves one nothing to do but mourn, and I’ve concluded this isn’t a good thing. Grief crowds in closely enough without the rest of life being shoved aside to make way for it. Am I scandalizing you?”

She peeked over at him, and Ian smiled at her. The library door was wide open, a footman posted directly outside. They were discussing novels, or possibly mourning, and she was concerned she might be shocking him.

Ian bent a bit closer and kept his voice down, as if they were exchanging confidences. “I found a great deal more solace in taking care of my father’s legacy and brawling with my brothers than I did sitting behind draped windows and reading scripture.”

Or getting drunk. He shook off that thought.

“Have you read this one?” He reached over her shoulder and pulled down a book. “It’s credited with sparking the revival of Scottish national pride, indirectly.”

“Waverley? This is by your Sir Walter.”

“It was so popular it gained him a dinner with George IV, and put Sir Walter in the position of managing the King’s visit here in ’22. I’m told I was brought to Edinburgh as an infant to see George sporting about in royal Stuart finery, but I have no recollection of it.”

She frowned at the book in her hand. “George’s advisors wanted him away from the Continent at that time, as I recall. He gained a great following here, though, didn’t he?”

“Temporarily, at least. In my grandfather’s time, we were still forbidden to wear the tartan and play our pipes. That George’s visit celebrated the very things long denied us was likely the source of that popularity.” But what sort of bluestocking was she, that she’d have a grasp of political history thirty years distant?

He was going to ask her, but she’d opened the book. Her frown became an expression of concentration as she stood right there and began to read. The only sound was the library clock ticking quietly on the wall, and still she remained absorbed in the book.

Ian realized how closely they were standing when he caught a whiff of lilacs from her person, a soft, pleasing scent that went with her retiring demeanor much better than the tart lemon had. She’d caught her hair back in a neat chignon, which left him with a curious desire to see her glossy black braid swinging over her hips again.

Maybe even a desire to have another of those chaste, maidenly little pecks to his cheek?

“I meant to thank you,” he said, the words surprising him. Step back, you idiot.

She glanced up at him, her expression questioning.

“At breakfast,” he clarified. “I presumed to use informal address with your cousin. You aided me in this regard.”

She blinked and closed the book with a snap. “I aided the cause of our digestion. I was not raised to stand particularly on ceremony, your lordship. My grandfather was merely a baron, or a… what is the Scottish equivalent?”

“A lord of parliament, or lord baron. I hope you enjoy the novel, Miss Merrick.”

He turned to go. There was work to be done, and she was regarding him with a peculiar light in her strange eyes.

“My lord?”

He stopped in midstride and turned to face her from a small distance. “Madam?”

From this angle, he could see that a curl had managed to escape from the black netting gathered over her nape. It was provoking, that curl. Laying against her neck, it disturbed the picture of order and calm she presented otherwise.

“I had thought…” She dropped her gaze from him to the book in her hands. “I don’t mean to presume, but if you were so inclined…”

Ian liked women. He enjoyed their company in bed and out, and he treasured the grace and sweetness they added to an otherwise difficult and burdensome existence. Still, something warned him to resist any queer starts on the part of this shy spinster who wandered barefoot in the dew and dispensed kisses at dawn.

He took one step closer. “You are a guest under my roof. You have only to ask, and any aid I can offer, any courtesy, is yours, Miss Merrick.” She was also his only ally in his efforts to wed the Daniels fortune, which fact excused his tarrying with her between the bookshelves.

She mumbled something, so he took one more step closer, and now he could see her cheeks were flaming.

“I beg your pardon, Miss Merrick?”

“Augusta.” She raised her gaze to his, her eyes lit with determination. “It might make your informality with Genie less difficult for her if you adopt the same address with Hester and myself. Just don’t…”

This was costing her, this declaration. For it was a declaration of some sort—maybe of support for his goal, or maybe of something else entirely.

“Just don’t?” he prodded. He put his hands behind his back lest he tuck that curl up into its rightful place.

“Don’t call me Miss Gussie, or Gus, or Miss Auggie, or—”

She could not have blushed any more brightly red, and abruptly, he did not want to look on her distress. Did not want to cause it.

“I’m Ian.” He interrupted her to say this. “I didn’t think your cousin would remain at table if I suggested we use first names only, though you may call me Ian if you like, and I shall call you Miss Augusta. My brothers will not refer to me by the title unless they are wroth with me, and it grows… awkward, to be Ian to this person, Balfour to that, my lord to the other.”

Her blush was fading, though this left a nice color in her usually pale cheeks.

“My grandfather said the same thing, said titles were confusing at best, and a damned lot of nonsense generally.” He thought she’d cause herself to blush again, but instead she gave him another of those shy, mischievous smiles. “A lady oughtn’t to use such language.”

She glanced around, as if someone might censor her for using “such language.”

“A guest in my home, particularly in my library, can use any damned language necessary to express herself. I hope you enjoy the book, Miss Augusta.”

And then he did something impulsive—something a little brave, a little selfish, and more than a little stupid. He gave her a peck on the lips.

A bit more than peck, really. Enough of a kiss to learn that she had soft, sweet lips and she hadn’t been kissed worth a damn in recent memory. Her hand brushed down his chest, a fleeting caress to him, no doubt a simple bid for balance to her.

When he straightened, her hand stayed on the wool of his morning coat for one moment, while both of them stood there, staring at her elegant, bare fingers smoothing down his lapel.

Temptation barreled out of the depths of Ian’s male imagination, ambushing commonsense with ideas Ian had no business thinking.

He would love to teach her to kiss.

He would love to take down all that black, shining hair and bury his face in it.

He would love to walk barefoot with her in the morning dew and lay her down in the cool summer grass…

While the sheer, beaming innocence of her smile said Augusta Merrick had no clue what he was thinking, no clue about any of it.

“I bid you a good morning, Miss Augusta.” She looked so pleased at the simple use of her name Ian would have turned from the sight even if there were not hours of work awaiting him elsewhere, and even if he had not flirted with lunacy by kissing her.

Not that anybody would mind if he dallied with her—she was a poor relation, and marriage was a calculating, unromantic business among the titled English… and lately the titled Scots, apparently.

He would mind if he dallied with her, and what a damned inconvenience that was.

As he made his way to the stables, Ian acknowledged he and Miss Merrick—Miss Augusta—had something else unexpected in common.

When he and his family had made the decision earlier in the year to file to have Asher declared dead, Mary Fran had insisted it was time for Ian to start using the title. He’d had a courtesy title—Viscount Deesely—but he’d never used it much. With the stroke of a pen on some arcane court pleadings, he’d become not Ian, but—presumptively and presumptuously—my lord, Balfour, Lord Balfour. The earl, but for the remaining legalities.

He could go entire weeks without hearing his own name, unless he was in company with his siblings. Inside, inside his very sense of himself, he felt the impending loss of some part of his identity with each use of more formal address. He couldn’t reverse this sense of loss; he relied on his family to do it for him by frequent use of his given name.

And now he knew he was not alone in his sense of isolation. Even proper little spinsters from the backwaters of Oxfordshire could suffer the same gnawing fear that if nobody ever called them by name, a part of them would eventually cease to be.

“They ride well for a trio of proper ladies.” Gil made the observation grudgingly, because women who rode well were women who’d had the luxury of spare time to learn, indulgent male relations to teach them, and good horses to learn on.

“Mary Fran could have come along if she’d wanted to,” Connor replied. “She’d rather terrorize the staff and concoct spells and incantations to shrivel the baron’s pizzle.”

“Hush, you.” Gil nudged his horse forward to keep in step with Connor’s younger mount. “Mary Fran hates that sort of talk.”

“Then she shouldn’t go dancing naked under the Beltane moon, should she?”

Gil did not ask whether Con was speaking figuratively or if he’d really seen their sister comporting herself without clothing by moonlight. God knew, Mary Fran was entitled to a little eccentricity, but Ian would be beside himself if she’d gone that far.

“The widow…” Con hesitated, his gaze on Mrs. Redmond, Miss Genie, and Miss Hester riding up ahead. They made a pretty picture even on the less-than-elegant mounts available from the Balfour stables.

“She seems the friendly sort,” Gil said, hoping to inspire Con to speak whatever piece he’d intended to speak. Miss Genie was petting her horse, stroking a gloved hand over the mare’s crest with a slow, easy rhythm that had the muscles over Gil’s shoulder blades relaxing.

“She’s the wealthy sort,” Con said. “Or was when she married into the Daniels family.”

“I’ve never held wealth against a woman.”

Con shook his head, so Gil resigned himself to patience. Con and Mary Fran were close, just as Ian and Asher had been close. Between those pairs of siblings, there had always been unspoken communication, while Gil struggled along parsing meaning as best he could and resorting to blunt inquiry more often than not.

“She said she does not want her niece to be married just for her wealth.” Con stretched up in his stirrups then settled back into the saddle. “Said that befell her, and she wouldn’t wish it on anybody. I told her I was sorry she’d been treated that way, which is hypocritical when my own brother intends the same thing toward her niece.”

Connor would loathe feeling hypocritical even more than he loathed running a glorified guesthouse for wealthy English pains in the arse. And of course he would apologize for a marriage Julia Redmond probably hadn’t even found truly bothersome.

“She wasn’t scolding you, Connor. She was making a chaperone’s version of small talk.”

Con indulged in one of his infernal silences, which might presage a silent exit, a grunted curse, or a startling profundity.

“She was confiding in me, or something.”

Gil knew himself to be handsome, knew Ian was handsomer, and knew Connor was… Connor was the braw fellow who ought to be watched and never was. His gruff ways, his indifference to refined dress and manners, and his rare, bold smile earned him all manner of female attention.

But confidences?

Gil ordered himself back to the topic at hand: “Ian isn’t an unfeeling brute. He’ll make Miss Daniels a passable husband.”

But as he spoke, Gil recalled the pathetic relief in Genie Daniels’s eyes that morning at breakfast when this outing—sans Ian—had been suggested. She’d had the trapped-prey air Gil felt every time he donned evening attire or stood up with a proper young lady at the local assemblies.

A look of such hopelessness, Gil had to wonder at it. “Let’s catch up to them.” He nudged his mount stoutly with his heels. “You can smooth the pretty widow’s feathers, while I flirt with the sisters.”

Connor said nothing, urging his horse to a canter and then falling in beside Mrs. Redmond, whose mare was winded enough that walking the rest of the way to the barn would be a kindness to the horse, if not exactly a kindness to her escort.

“Come, ladies, I can show you a path that will let us canter through the woods.” Gil offered them the smile useful for getting him his ale before any other patron, but only Hester returned it.

“I’m not in shape for any canters through the woods,” she said. “Particularly not after sitting on that train for an eternity. You and Genie go, and I’ll keep Aunt company.”

“Miss Genie? It cuts through the woods, where Her Majesty sometimes likes to walk and His Highness has been known to ride.”