What a Lady Needs for Christmas

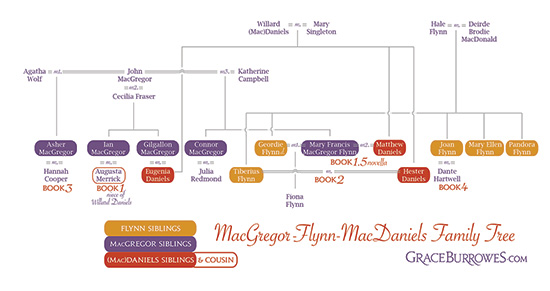

Book 4 in the MacGregor series

Lady Joan Flynn needs a husband—any husband—if she’s not to find scandal and mischief under her Christmas tree. Scottish wool magnate Dante “Hard-hearted” Hartwell needs an aristocratic wife to gain access to the financing that will keep his wool mills secure and safe. Can holiday magic weave an expedient match into true love, and spin wary differences into trust?

Bonus Materials →

Enjoy An Excerpt

Chapter One

“But, Papa, we should help the lady!”

The childish soprano carried over the hum and bustle of a crowded train station, jabbing at Lady Joan Flynn’s composure like a stray pin making itself known in her bodice as she swept into the first turn of a waltz.

Joan nonetheless beamed an unfaltering smile at the ticket master.

“Surely you can find one seat on the westbound train? I have little luggage and need passage only as far as Ballater.”

Her luggage consisted of a carpetbag clutched in her right fist. That she’d fled Edinburgh without even packing a single trunk of clothing spoke of Joan’s first experience with true desperation.

“Papa, we’re going to Ballater. We should help her.” The girl’s voice, if anything, had grown louder.

“Like I said. Nary a single seat left, ma’am. Ye’ll have to step aside now.” The old gnome made his pronouncement with the malevolent glee of a clerk exercising his petty—but absolute—power.

Joan most assuredly did not step aside.

“Christmas is coming. We’re supposed to be nice, Papa.”

The child’s intentions were good, though Joan wanted to turn around and wrap her scarf around the little dear’s face. A soft, rumbling Gaelic burr replied to the girl, while Joan let her smile wobble as she fished a handkerchief from her reticule—the white silk with the holly-and-ivy trim around the edges.

“I’ll ride with the livestock,” Joan said, touching the handkerchief to the corner of her left eye, where tears would, in fact, soon gather. “I must rejoin my family, and they’ll be so worried, and—”

White eyebrows climbed aloft on the ticket master’s pink forehead, then crashed down as inspiration struck.

“Ye canna ride with the beasts. ’Tis against regulations.” He flourished the r of regulations, then swooped on the g, an officious Scot relishing the delivery of bad tidings—rrrreg’ulations. “Ye can buy a ticket for Monday’s train.”

No, she could not. “But I have nowhere to stay until Monday. I have the fare if—”

“Her ladyship will ride with us,” said that same rumbling baritone from directly behind Joan.

“Because we’re going to Ballater,” the child added helpfully.

Joan turned without giving up her place at the counter. “Sir, that’s most kind of you, but if we have not been introduced—”

Except thank all the angels, Joan had been introduced to the man, not three weeks past.

“Lady Joan.” Mr. Dante Hartwell bowed, as much as man can bow when he has a small child perched on his hip. “You are welcome to travel with us. Charlie reminds me that we’re going as far as Ballater ourselves, and we have plenty of room.”

Charlie was of the female persuasion, though she had her father’s sable hair and a lighter version of his green eyes. He whispered something in the girl’s ear, then pressed a quick kiss to her cheek, which had Charlie grinning at Joan.

Mr. Hartwell’s expression was not nearly so genial.

In Joan’s experience, Mr. Hartwell and geniality were not well acquainted, though if Joan had spoken out of turn at Charlie’s age, her lordly father would not have whispered his scold or followed it up with a kiss.

“Your offer is generous, Mr. Hartwell, but I cannot travel with you unchaperoned.” Or could she?

“You were willing to travel with the beasts,” he shot back. “I smell a bit better than they and can offer you more than straw and a cold loose box for the duration of the journey.”

“Papa smells good,” Charlie supplied, “but not as good as Aunt Margs. She took Phillip ’round back.”

“Madam,” the ticket master interrupted. “Ye’re holding up the line, and ye either travel with the gentleman and his family or ye bide here until Monday’s train. Next!”

Joan had danced with Dante Hartwell and found him lacking many of the attributes she associated with a proper gentleman. He neither gossiped nor flattered nor took surreptitious liberties in triple meter.

In short, despite his many detractors—some called him Hard-Hearted Hartwell—she’d liked him. Little Charlie was also right: her papa smelled good, of wool and heather, unlike the fellows wearing their cloying Paris fragrances in ballrooms already redolent of manly exertion. Mr. Hartwell savored of simple tastes, fresh air, and Scotland. Then too, his hair stuck up to one side, as if Charlie had made free with her papa’s coiffure.

“Your sister is traveling with you, Mr. Hartwell?”

“Aye. Is this your only bag?” He appropriated the carpetbag from Joan’s grasp.

“Aunt Margs has lots of bags,” Charlie said. “I think our Christmas presents might be in them, but Aunt says it’s all her dresses.”

The ticket master had apparently had enough. “Madam, I really must insist that ye—”

“Stow it, MacDeever,” Mr. Hartwell said. “Lady Joan travels with us, and ye’ll no’ be spoutin’ off about yer pernicious regulations if ye want my continued custom.”

The eyebrows climbed halfway to the North Pole, but MacDeever remained silent.

“Thank you, Mr. Hartwell, and thank you, Charlie,” Joan said, for it appeared she was to share a compartment with Mr. Hartwell and his family. How she’d travel from Ballater to Balfour House, she did not know, but surely hacks, drays, and other conveyances could be had for a few coins at a busy train station.

Because a few coins was all she had.

“Aunt Margs!” Charlie bellowed, waving madly as they tromped out onto the platform. “We’re being good. Papa says Lady Joan is to travel with us because we’re going to Ballater and she only has one bag.”

The girl had shouted directly in her father’s ear, and yet, Mr. Hartwell simply stood in the freezing wind, his bare knees exposed by his kilt. As rescuers went, he was an unlikely specimen. Pine swags draped over the station’s entry luffed above him; he had Joan’s purple brocade traveling bag in his big hand, a child affixed to his hip, and a grouchy expression on his face.

A petite woman approached in a truly horrid green cloak—the hem wasn’t evenly stitched, for pity’s sake, though the wool looked to be of passable quality—leading a small dark-haired boy by the hand.

“Dante, has someone joined our party?” She spoke with the soft, broad vowels of the native Scot, and while her brother was tall, dark, and lean, Margaret Hartwell was short, fair, and comfortably rounded.

And smiling. Margaret had the sort of open, friendly smile that would put any guest at ease and warm any heart.

“Lady Joan Flynn, may I make known to you my dear sister, Margaret,” Mr. Hartwell said, his tone as close to warm as Joan had heard from him. “The rascal by her side is my boy, Phillip. Phillip, make your bow.”

“Pleased to meet you, ma’am,” the child piped, flopping over at the waist.

“Miss Hartwell, Master Phillip, the pleasure is mine.” Particularly when it was Margaret’s presence that allowed Joan to accept Mr. Hartwell’s kind—if begrudging—offer.

As for the “boy”—a gentleman of more refined breeding would have referred to the child as his son—he looked entirely too angelic. Dark hair in need of a trim framed green eyes too serious for such a small child, but then, what did Joan know of small children?

Much less than she needed to.

As Joan cast around for small talk, Mr. Hartwell strode off toward the back of the train.

“We’d best hurry,” Margaret said. “Dante likes to oversee the loading of the luggage, and he’ll forget that Charlie shouldn’t be out in this weather any longer than necessary. Normally Dante would make this journey in a single day, but with the children…”

She bustled off after her brother, though why Mr. Hartwell had to oversee the porters, Joan could not fathom. Her brother, Tiberius, would have, because Tye was the most responsible fellow ever to stand in line for a marquessate, but Mr. Hartwell’s prospects were nowhere as daunting.

Mr. Hartwell was in trade, a fact Joan had heard whispered behind fans, mentioned at card tables, and casually brought up in the course of numerous dances. The longer Mr. Hartwell had gone without stumbling on the dance floor, insulting the hostesses, or showing up for a Society ball in riding attire, the more frequently Joan had heard of his plebeian antecedents and unfortunate preoccupation with commerce.

A whistle blast signaled those milling on the platform to board their respective compartments, and at the end of the train, Mr. Hartwell, the child on his back now, oversaw no less than three porters stowing bags in the last car.

“Should we find our compartment?” Joan asked as she caught up with Margaret and Phillip.

“We’re in here,” Margaret said, gesturing vaguely toward the passenger cars. “Dante, that child should be out of this weather. You will put her down this instant.”

“I’m helping,” Charlie said, clearly enjoying her perch on her papa’s back.

The girl might have weighed less than a sparrow for all the notice her father took of her.

“The fools put the small trunks in first,” Mr. Hartwell groused, “which means the largest trunks have nowhere to go but atop the heap, and that isn’t the most stable—”

He broke off and leveled a look at Joan.

“Take Charlie.” He peeled the girl off his back in a smooth display of one-armed muscle and more or less threw her in Joan’s direction. “Charlene, mind Lady Joan while I—”

A spate of cursing in Gaelic followed as Mr. Hartwell disappeared into the baggage compartment, and three porters vacated it, rather like rats scurrying for safety upon the arrival of a particularly large, ferocious terrier.

“Dante likes things just so,” Margaret observed in what had to be a diplomatic sororal understatement. “Let’s get these children out of the weather, shall we?” She led Phillip to the steps and allowed him to scamper onto the train ahead of her.

“You can put me down,” Charlie said. “Papa only carries me when I can’t keep up. His legs are longer than mine.”

“His legs are longer than most people’s,” Joan said, taking the child by the hand, though she’d rather liked Charlene’s solid weight against her hip. “Shall we find our seats?”

Charlie peered up at her, her expression perplexed. “We don’t have seats. We have the last two cars of the train.”

![]()

“She’s hiding from you,” Dante said, wondering how much his guest’s cloak had cost. Contrasted with Lady Joan’s red hair, the velvet was so purple, it shimmered in waterfalls and waves of light that had no visible source. A dark, luminous purple that shouted—quietly, mind—of warmth, pampering, and class, even as it made a man’s palms itch to stroke it.

“Miss Hartwell is hiding?”

Miss Hartwell. Not, “m’ dear wee sister, Margs,” or whatever Dante had said when he’d introduced Margs to her ladyship. A powerful thirst came upon him, the same thirst he experienced whenever he was forced to prowl around the parlors and ballrooms of his betters.

And what a waste of time and fussy tailoring that had been.

“Aye. Margs is shy. May I offer you something to drink, Lady Joan?” Margs was scheming and determined too, which accounted for her pressing need to “see the children settled” in the other car.

“Have you any tea, Mr. Hartwell? I left Edinburgh in something of a hurry.”

Her very diction carried light and elegance, and yet bore a certain warmth, as did she. Dante owed this woman—and he always paid his debts—but he also liked her.

“Tea, we have, and we’d best drink it before it cools.” The train had yet to pull out of the station, so pouring would be little challenge—but for whom?

Lady Joan sat at the small mahogany table secured beneath the curtained window, while Dante prowled around the parlor car like a bear in a tinker’s wagon.

Did he sit across from her?

Ask permission to sit?

Serve her while standing, as if he were a bloody footman? Sit and then serve her?

Ask her to pour?

Would Father Christmas please bestow on one hardworking Scotsman some command of the manners and mannerisms necessary to move among those with titles and wealth?

“Do have a seat, Mr. Hartwell, and I’d be happy to pour out.”

Dante retrieved the tea service from the sideboard, set it down before her with a small “clank,” and wedged himself into the seat across from her.

Train cars were built to the scale of fairies, though for all her height, Lady Joan looked comfortable enough.

“So what were you about, stranded at some widening in the cow path halfway to the Highlands?”

He should probably have stashed a “my lady” or two somewhere in that question. She belonged in the ballrooms, the elegant parlors, the best shops, while he did not.

“I was all but going to pieces,” she said, her smile wry. “I cannot thank you enough, Mr. Hartwell, for your kindness and generosity. How do you take your tea?”

Dante Hartwell was known for neither kindness nor generosity.

“If that’s your idea of going to pieces, then I’m not sure what you’d call some of Charlie’s worse behaviors. The girl can be—”

Just like her father, but Dante didn’t say that. He was too absorbed watching a lady execute the gracious and baffling ballet of the tea service. Lady Joan had lace at her wrists, the white a brilliant contrast to her deep purple sleeve. The dress wasn’t as dark a hue as the cloak, but complemented the cloak and was every bit as shimmery. Against the purple velvet, the dab of lace looked like snow on violets or hyacinths or some damned posy.

“Your daughter is charming,” Lady Joan said. “Shall I add cream and sugar?”

“Nay.” He accepted the tea and downed it in a swallow. It was hot, and—

Not by word, deed, lifted eyebrow, or firming of her rather full lips did Lady Joan call Dante on his misstep. He rather wished she had.

“I bungled that,” he said, setting the silly little cup back on the tray. The service was sized for one of Charlie’s endless tea parties, not for use by thirsty adults. “I was supposed to wait for you to serve yourself.”

His entire foray to Edinburgh had been one long exercise in bungling, and he was weary to his soul of it. When he’d been on the point of retreating to Glasgow, tail between his figurative knees, Lady Joan had given him a waltz, and shown every pretense of enjoying his company. That single dance had silenced the worst of the gossips, and prompted invitations from all manner of titled hostesses.

“You were supposed to enjoy your tea,” Lady Joan said, pouring him another cup. “You should hear my brother prosing on about tea, and how the empire would fall apart if we were denied our tea for a week straight. He’s full of opinions, is Spathfoy.”

This time, Dante let the cup sit on the tray until the lady had poured for herself. “The empire’s finances would certainly falter if tea consumption stopped.”

Another bungle, referring to commerce that way. He was in fine form today.

She took her tea with cream and sugar, and in her hands, the little porcelain cup with the gilded rim looked perfect—also a tad shaky.

“My nerves would falter as well. This is very good.”

“Bit of Darjeeling in it, because Margs prefers it. You’ve avoided my question, Lady Joan. One doesn’t find daughters of English marquesses milling about wee, cold, smelly Scottish train stations every day.” Not alone, not without their luggage, not desperate for a seat on any westbound train.

She cradled her tea in her hands, giving Dante a moment to study her. The Lady Joan he’d come across socially had never had a hair out of place, never so much as a crumb on her bodice or a less-than-pleasant expression on her lovely face.

This Lady Joan’s green eyes were shadowed with fatigue, her red hair was coiled in a simple chignon any serving maid might use for Sunday services, and her fine brows were slightly pinched, as if a worry had taken up residence behind them.

“One shouldn’t find daughters of English marquesses in such condition,” Lady Joan said, trying for humor and failing.

While Dante was trying for manners and not exactly succeeding.

He pushed the plate of scones at her then nudged the butter to her side of the tray, because he wanted to give her something to ease her distress. His bare knee bumped the same portion of her velvet-clad anatomy under the table, because she was no more built to fairy proportions than he was.

“You’re trying to concoct a falsehood, my lady.” Perhaps that was what creased her brow so she resembled Charlie on the verge of a bouncer. “You needn’t bother. Have something to eat.”

While she remained perched on the edge of the seat, teacup in her hands, Dante split a scone, slapped some butter on both halves, set it on a plate, and passed it to her.

“Many have nothing to put in their bellies this winter. You aren’t among them today. Eat and be grateful.”

He’d sounded like his papa—he sounded like his papa more often the older the children grew, and this was not a happy realization.

And yet, Papa hadn’t been entirely wrong, either. The parlor car boasted a small Christmas tree on the table in the corner, complete with tiny paper snowflakes and a pinchbeck star. The cost of the tree and its trimmings would likely have bought some child a pair of boots.

“This scone is very good,” Lady Joan said, tearing off a bite, studying it, and putting it in her mouth. “Your hospitality is much appreciated, Mr. Hartwell. Your discretion would be appreciated even more.”

The silver service rattled as the train lurched forward then eased into a smooth acceleration away from the station.

While Lady Joan made deft references to Dante’s discretion.

“You’re not trying to insult me.” Dante didn’t feel insulted, exactly, more like excluded—again. Excluded from the ranks of gentlemen, whose faultless discretion would be evident somehow in their very tailoring and diction.

“I mean no insult,” Lady Joan replied, munching another bite of scone and looking…bewildered. “I’m trying to trust you.”

“Try harder. I don’t gossip, and I don’t take advantage of women who find themselves in precarious circumstances. I’ve a daughter, and a sister, and I employ—”

She peered at him, as if perhaps he might have sprouted an extra head or two in the past minute.

“The rumors in Edinburgh were that you were looking for a wife, Mr. Hartwell. Nobody mentioned that you had children, though.”

He recalled something then, about their passing interactions among the Edinburgh elite: he’d seen her dancing most often with Edward Valmonte, a mincing, smiling, nasty bugger of a baron—or possibly a viscount.

Pretty fellow, though, all blond grace and heavy scents. Lord Valmonte had done a lot to queer Dante’s chances of finding a wife among the titled and moneyed set Valmonte called his family and friends.

“Keep your secrets then,” Dante said, buttering another scone for her. “You’re safe here, Lady Joan Flynn, and while I cannot call myself a gentleman, I can be discreet.” He rose, though in the presence of a lady, some damned protocol probably applied to that too. “I’ll send Margs to you. The sofa there is a decent place to nap, and we’ll not make Aberdeen for two hours at least.”

He headed for the door that would lead him across the platform to the other car.

“My maid fell ill,” Lady Joan informed the bite of scone she’d accepted. “She had to turn back for Edinburgh, but I wanted to push on. My family is gathering in anticipation of the holidays, and I wanted—I have to be with them.”

She wasn’t lying; she also wasn’t allowing him to aid her any more than was necessary.

“To be with family for the holidays is a fine thing,” was all he could think to say. “Margs will be along directly.”

But not immediately, because as Dante well knew, sometimes, the only kindness a person in difficulties could accept was solitude in which to contemplate their troubles.

![]()

“We’re going visiting,” Charlie informed Joan, scrambling into the banquette flanking the table. “We have to be on our best manners, or Father Christmas will only give us lumps of coal.”

“Coal costs money,” Phillip added from across the parlor car. He sat on the sofa, his booted feet dangling above the floor, a storybook open in his lap.

“Papa has lots of money,” Charlie assured Joan earnestly. “Does your papa have lots of money?”

“I’m sure I wouldn’t know.” Papa and Tye were both quite well set up.

“Our papa does.” The child buttered herself a scone and inspected both Joan’s teacup and the one Mr. Hartwell had used. “Papa owns tex-tile mills. Tex-tiles are like my dress.”

“Textiles are fabrics,” Phillip added. “Everybody needs textiles.”

“Or”—Charlie’s eyes danced as the door to the platform opened—“we’d be naked!”

“Charlene Beatrice Hartwell,” Margaret said, advancing into the car. “Mind your tongue.”

Charlie scrambled down, her scone in her hand. “Well, we would be. That’s what Papa says, and you say we must mind Papa.”

Papa, who had disappeared into the next car just as Joan had been about to ask him what, exactly, he’d heard about her in all the smoking rooms and gentlemen’s retiring rooms of Edinburgh’s best houses.

Mr. Hartwell would have told her, too, honestly and without judging her for what the gossip implied. How she knew this had something to do with his magnificent nose and with the manner in which his kilt flapped about his knees. His steadfast demeanor was also evident in the way he cursed in Gaelic and tossed full-sized trunks around as if they were so many hatboxes.

Even as he handled his daughter with much gentler strength.

“Charlie, perhaps you’d like to finish that scone sitting here next to me,” Joan suggested. “If the train should lurch while you’re larking about, you could choke.”

Though he’d fled to the other car, any distress to Charlie would likely distress her papa greatly too.

When Charlie shot a curious look at Phillip and his storybook, Joan stroked the velvet cushion next to her seat.

“I thought I might pour you a spot of tea, and you too, Miss Hartwell. The tea will soon grow cold, and Mr. Hartwell said we’re a good two hours from Aberdeen.”

“I like tea!” Charlie skipped over to the table, leaving a few crumbs on the carpet. “Phillip doesn’t, not unless it has heaps and heaps of sugar.”

Phillip did not deign to reply, his little nose being quite glued to his book.

“I prefer some sugar in my tea as well,” Joan said.

Now, Phillip raised his face from his stories long enough to stick his tongue out at his sister, but only that long. Charlie returned fire, grinning, then resumed her seat across from Joan.

“You two,” Miss Hartwell muttered, sliding in next to Charlie. “They aren’t bad children, exactly. Dante says they’re high-spirited.”

“Papa says we’re right terrors,” Charlie supplied, taking another bite of scone. “I like being a terror.”

While Miss Hartwell looked as if she’d expire of mortification.

“Even a terror must know how to serve tea,” Joan said, passing the girl a plate. “And even a terror knows that somebody must clean up all the crumbs strewn about, and cleaning up isn’t much fun, is it?”

Charlie looked at her last bite of scone as if she’d no idea how the food had arrived into her hand. Her shoulders sank as she studied the carpet. “I made a mess. I should clean it up, or Papa will be disappointed in me.”

“Only a few crumbs worth of disappointment,” Joan said, because she knew well the weight a papa’s disappointment might add to a daughter’s heart, and would soon know it even better. “We’ll tidy up when you’ve had some tea.”

How to serve tea was a lesson a lady absorbed in the nursery, her nanny guiding, her dolls in attendance. Joan’s own mama had joined in those earliest tea parties and turned the entire undertaking into a game, eventually adding real tea and—Mama had a genius for raising little girls—real tea cakes.

“What’s the most important thing about serving tea?” Charlie asked, and the ring of the question suggested Papa, in addition to the other pearls of wisdom he showered upon his adoring daughter, tended to prose on about Most Important Things.

“The most important thing,” Joan said, “is to make your guests feel welcome, otherwise, they won’t enjoy their tea, or even their tea cakes.”

“It’s not to avoid spills?” Miss Hartwell asked.

Interesting question, and Miss Hartwell offered it hesitantly.

“Spills are inevitable.” Spills on the tea tray, and in life too, apparently. “That’s why we have trays and saucers and extra serviettes. If the hostess spills a drop or two, then a guest who makes a similar slip won’t feel so ill at ease.”

Joan poured out for Miss Hartwell, though to do so was presumptuous when Miss Hartwell’s brother owned the parlor car—and everything in it.

![]()

As a younger man, Dante had ended up in bed with any number of strangers. The cheaper inns were like that—a man might share a room, even a mattress, with some fellow he’d never met, share a table with a family he’d never see again. The locomotive had conferred that same quality upon the traveling compartment, where impromptu picnics, shared reading, and gossip turned the cheaper cars of each train into a series of temporary traveling neighborhoods.

Dante hadn’t expected that his private car would fall prey to such informality, but there Lady Joan lay, cast away with exhaustion on the settee bolted to the wall.

She did not fit on her makeshift bed.

Her ladyship was tall for a female. Had she been male, Dante would have called her “lanky,” but because she was not male, the applicable term was probably “willowy.” The luminous dark purple cloak swaddled her to the chin, but one half boot dangled free of her frothy lavender hems, an escapee from warmth and decorum, both.

The question that dogged his very existence of late loomed once again: What would a gentleman do? He’d probably retreat to the other car, where Charlie was busy making enough noise for three little girls, a pair of small boys, and a barking hound.

If the gentleman were very pressed for time, would he ignore his guest, sit at the fussy little tea table, and plow through Hector’s stack of figures? Would he close his eyes for a moment and snatch a badly needed nap when nobody was looking?

That way lay two wasted hours, and yet, Hector’s reports were a daunting prospect.

Lady Joan looked daunted. Her eyes were shadowed with fatigue, and on this rocking, noisy, stinking train car, she was fast asleep.

In addition to her half boot and frilly hems, a slender, pale hand now emerged from under the purple velvet. A row of small nacre buttons started at the wrist of that hand—more subtle luster—marching right up the underside of her forearm to disappear under her cloak.

The poor woman would take forever to get dressed.

Or undressed.

Trying not to make a sound, Dante sorted through the half-inch-thick packet of documents he’d taken from the top of his traveling valise when he’d fled the other car.

Five minutes later, he was studying the rise and fall of Lady’s Joan’s chest beneath her velvet swags. Her stays did not confine her much, was his guess, and maybe that accounted for the freedom she exuded in her movement and in her smiles.

“You’ve caught me,” she said, opening her eyes. She started to stretch, her boot hit the end of the settee, and she subsided beneath her cloak. “Not well done of me, falling asleep where any might chance upon me.”

“I meant only to retrieve my reports. I’ll go back to the other car,” Dante said, shuffling the reports into a stack but making no move to rise.

“No need,” her ladyship said, pushing halfway to sitting and then stopping, awkwardly, half reclining, half sitting. “Gracious. I seem to have become entangled.”

She could not lift her hand to peer at the difficulty, because her lacy cuff was caught on one of the buttons fastening the upholstery to the settee’s frame.

“Hold still.” Dante extracted his folding knife from his coat pocket. He was across the parlor car in two short strides and on his knees before the settee. “I’ll have you free in a moment.”

Dante still wore his reading glasses, so he could see that three of those tiny, fetching buttons—that would inspire a man to stare at her slender wrists by the hour—were now twisted up in the lacy cuff. He flipped open his knife, prepared to deal summarily with troublesome fashions, when Lady Joan’s free hand landed on his shoulder.

“Please, do not.”

“You’re trapped, my lady. A quick slice, and you’ll be free. You can stitch up the lace by the time we’re halfway to Aberdeen.”

Her contretemps put them in close proximity, Dante kneeling before the settee, the lady’s cloak and skirts brushing his knees. What he felt crouched beside her semi-recumbent form was not a temptation to sniff at her spicy fragrance, not a desire to unbind all that fiery hair, but rather, an itch to divest her of the velvet covering her from neck to toes.

“But that’s a knife, Mr. Hartwell.”

“Aye, and I keep my blades honed.”

“One doesn’t…velvet and lace should not be…a knife is…oh, bother. Give me a moment.”

He knelt before her, feeling helpless and stupid, while she tried to use her free hand to worry the buttons from the lace. She was doomed to fail—one hand wouldn’t serve for this task—and Dante had every intention of allowing her to struggle while he returned to the boring safety of Hector’s reports.

Except, when she bent forward to work at the trap she’d fallen into, Lady Joan shifted so her décolletage was a foot from Dante’s face. The spicy scent of her concentrated, nutmeg emerging from undertones of cedar, clove, and even black pepper.

The lace of her fichu was a cross between pink and purple—she could doubtless tell him the name for that shade in French and English both—and the cleft between her breasts was a shadowy promise between two modest, pale female curves.

“I can’t get it,” she muttered. “Drat this day. I can’t even properly sneak a nap or occupy a settee.”

She occupied a settee quite nicely, but one didn’t argue with a lady. Dante knew that much.

“Let me have a try.” He scooted two inches closer and covered her hand with his own. “You’re at the wrong angle.”

She slid her hand out from under his. “Please do. At some point I must leave this train, and dragging furniture behind me will make that a difficult undertaking.”

“You could always take the dress off,” Dante said, studying the problem. Because of the way she’d twisted things up, the trick would be to free the buttons in sequence, top, middle, bottom. He carefully spread the lace around the top button, making an opening for the button to slip through.

The quality of her ladyship’s silence distracted him from the buttons.

What had he said? Something about taking the dress—

She stared at him, her brows drawn down, her mouth a flat, considering line. Then, the corners up her lips turned up, hesitantly. “Taking off the dress would extricate me from the settee’s clutches, though it might be a bit chilly, too.”

She was not chilly. When Dante considered the picture she’d make, all lace, silk, and pale garters—probably embroidered with lavender flowers—he wasn’t chilly either.

“I’ll have you out in a moment,” he said, focusing on the two remaining buttons.

The third button was not, in fact, the charm. Number two obeyed Dante’s fingers as he created another temporary button hole for it, but the last button was tightly caught, and Dante’s efforts to rearrange the lace resulted in a small tearing sound.

“Oh, no,” Lady Joan moaned, trying to still Dante’s fingers by covering his hand with hers. Her palm was cold, her grip stronger than he would have thought.

“Ach, now, my knife—”

“No. No knives, not on my cuffs, not on my sleeves, not on my buttons.” Her tone was pleading rather than imperious, but she’d covered the junction of button and lace with her hand so Dante could not have freed her if he’d wanted to.

The moment turned awkward, with the lady trapping his hand against her wrist, as if she’d protect a bit of cloth from the infidel’s knife.

A single hot tear splashed onto the back of Dante’s hand, and the moment became more awkward still.

Chapter Two

Joan did not have a favorite fabric, a favorite color, a favorite style of dress. She loved them all—right down the smallest lacy cuff—with a dangerous, undisciplined passion.

Her passion for fabric would soon cost her everything she held dear.

“I’m sorry,” she said, trying to straighten, but even this small attempt at dignity was thwarted by the perishing sofa. “I’m fatigued, and the day has been t-trying, and no matter what I—”

“There we go,” Mr. Hartwell said, lifting Joan’s wrist from the arm of the sofa. “You’re free.” He dug in his sporran for a handkerchief, which Joan accepted. Her white silk handkerchief was for show, and these tears were all too real.

“My thanks, Mr. Hartwell, I do apologize. I’m not normally so easily—”

A large, blunt finger touched her lips. “You’re about to spew a falsehood, another falsehood. In case it has escaped your notice, we are alone in this train car, and nobody’s on hand to whom you need lie.”

Lie was a blunt word, and Mr. Hartwell’s touch was far from soft, but the kindness in his eyes was real. Rather than fall into that kindness, Joan smoothed her fingertips over the corner of the plain cotton handkerchief.

“Who embroidered this?”

“Margs.”

“She does lovely work.” The small square was monogrammed in green with exquisite precision. “She must have excellent eyesight.”

Mr. Hartwell took the place beside Joan on the sofa, draping her cloak over the arm. “She’s determined, is Margs. Why were you crying?”

A gentleman wouldn’t ask, but a friend—if Joan had had a friend—wouldn’t have let the matter drop.

“Allowing me to share your parlor car doesn’t mean I can inflict all my petty difficulties on you, Mr. Hartwell.”

Though her present difficulties would be the ruin of her, if not of her sisters too.

“I was married,” her companion said. “Sufficiently married to have two wee bairns, and that means I have a nodding acquaintance with women, if not with ladies.”

Soon, Joan wouldn’t be worthy of such a distinction. The notion prompted more tears, not because she would be a discredit to her title, but because her family would be so disappointed in her.

She was disappointed in herself, come to that.

Mr. Hartwell wrapped a heavy arm around Joan’s shoulders, and she gave in to the comfort he offered. For long moments, she simply curled into the solid bulk of him and cried, all dignity, all self-control gone while the train rumbled and swayed ever northward.

When her upset had eased to sniffles, his arm was still around her shoulders, and she could not have moved off the sofa to save what remained of her reputation.

“The wool of your coat contains a quantity of merino,” she said, rubbing her cheek against his sleeve. “The blend is lovely, if unusual. Why aren’t you horrified when I cry?”

“I’m Charlie’s da. You think a few tears will put me off?”

Joan’s father would not have sat with her like this, a quiet, tolerant presence offering handkerchiefs and a calm that had something in common with loyal hounds and plow horses.

“Tears put me off,” she said, dabbing at her cheeks and trying to sit up. “I must look a fright.”

His big hand settled on the side of her neck, his callused palm an interesting contrast to her velvet and lace.

“You look frightened, Lady Joan, and tired, and much in need of a friend. You have nowhere to run for the next two hours. The children have gone down for naps, Margs is reading some improving tract, and you have no one else to talk to. I am not—”

Joan waited while Mr. Hartwell chose his words, because she liked the sound of his voice, and she had a soft spot for merino blends.

“I’m not refined,” he went on, “not of your set, but I have a few resources. I’ll help if I can.”

He was rumored to be wallowing in filthy lucre.

“You are helping. You are helping me flee Edinburgh, where I am sure scandal is about to erupt all over my good name. I was foolish.”

“Edinburgh must breed foolishness, then, because I certainly did not acquit myself well there either.” His admission was grudging, self-mocking, and endearing.

His thumb rested right below her ear, and abruptly, Joan was assailed by a memory of Edward’s nose mashed against her neck. He’d been on top of her, breathing absinthe all over her and wrinkling her gown terribly. If she could forget a man nearly crushing her, what else had she forgotten about last night?

“I cannot imagine you being foolish, Mr. Hartwell. You strike me as the soul of probity.” He was certainly the soul of sober colors, at least when he took to the ballrooms. No extravagant jewels, stickpins, or even formal Highland dress, which was common enough in Scotland.

Joan knew with a certainty that Mr. Hartwell wouldn’t slobber on a woman’s neck while he yanked at her bodice.

“I am the soul of low birth,” he said. “I should know better than to impose myself on my betters, but Margs needs a husband, and someday, Charlie and Phillip will need prospects their papa’s money cannot buy. I sought to start securing those prospects, and found the task utterly beyond me.”

Joan set aside her troubles for a moment—they weren’t going anywhere, heaven knew.

“You’re giving up on Polite Society after a few weeks of waltzing and swilling punch? This isn’t even the social Season, Mr. Hartwell. The prettiest debutante knows she must campaign for more than a few weeks.”

“And I am not the prettiest debutante, am I?”

He was in trade. Even if he had been the prettiest and best dowered debutante, or the handsomest, most charming bachelor, being in trade would follow him everywhere.

“You sought a wellborn wife, I take it? One who could open doors for your daughter and your sister?”

He tugged off his glasses and slipped them into a breast pocket. “I certainly haven’t any need to polish my waltzing skills.”

“You waltz beautifully. You don’t haul a woman about, as if it’s her privilege to smile and simper at your every word while you step on her toes and leer at her attributes.”

She should not have been that honest. She should have asked him which clan plaid was draped over his knees. The pattern was mostly blue and black, with thin intersecting stripes of red and yellow. A hunting tartan, possibly.

“Was one of these leering, stomping idiots involved in your foolishness, Lady Joan?”

The train whistle sounded, and beyond the velvet curtains caught back at the parlor car’s windows, snow had started. The landscape was bleak, and Joan’s mood more bleak yet.

She said nothing.

“I’ll tell you a story, then. Charlie vows I’ve a gift for telling a tale,” Mr. Hartwell said, easing back a fraction against the cushions, as if getting comfortable. “Once upon a time there was a lovely, graceful young woman whose papa was a marquess—an English marquess, the very best sort of marquess to be. She was friendly and kind, also every inch a lady—and there were many inches, for she was tall. Along came a young man, probably handsome, full of charm. He’d be blond, for the handsomest young men usually are—also English somewhere not too far back in his pedigree. Does the tale sound familiar?”

Had he already heard the gossip? Not twenty-four hours after the debacle, and even Mr. Hartwell, who could not belong the best clubs or have the ear of the worst gossips, seemed to know the particulars.

“Go on.”

“The handsome young swain exerted his charm, he made promises—he served the young lady strong drink and stronger compliments, and he made more promises. He took liberties, and the young lady was perhaps flattered, to think she’d inspired a handsome, charming man’s passions to that extent.”

Joan’s head came up. “I wasn’t flattered. I was muddled.” Also horrified.

“You have made a wreck of my handkerchief,” Mr. Hartwell observed, gently prying the balled-up silk from her grasp.

“I’ve made a wreck of my life.”

![]()

Nothing good came from a fellow involving himself with damsels in distress. Dante knew this, the way a lad raised up in the mills knows to keep his head down and his hands to himself, lest some piece of clattering machinery part him from same.

Rowena had been a damsel in distress, and look how that had turned out.

And yet, Charlie hadn’t allowed him to ignore Lady Joan, and some vestige of chivalry known to even clerks, porters, and wherry men hadn’t allowed it either. Now that he’d rescued his damp handkerchief from her grasp, she traced the lines of the Brodie hunting plaid draped across his thigh.

Joan Flynn was a toucher, a fine quality in a woman, regardless of her station. Charlie was a toucher. She had to get her hands on things to understand them, the same way Dante had to take things apart to see how they fit together.

“You have not made a wreck of your life, my lady. The worthless bounder who stole a few kisses will keep his mouth shut about it, and not because he’s a gentleman.”

Gentlemen tattled on themselves at length over their whiskey and port, and called it bragging. Worse than the waltzing and bowing, listening to their manly drivel had affronted Dante’s sensibilities.

“Why should he keep his mouth shut?”

“Because it reflects badly on him that he’d take those liberties. Your papa could ruin the man socially, to say nothing of what your mama might do. Pretty English boys who take advantage of innocent women need their social consequence if they’re to pursue their games.”

Her brows drew down in thought, which was an improvement over tears, and her fingers stroked closer to his knee.

“You are certain of your logic, Mr. Hartwell.”

“I am certain of young, charming Englishmen.” He was also certain that Lady Joan ought not to be cuddled up with him this way, now that her tears had ceased.

And yet, he stayed right where he was.

She wrinkled her splendid nose. “He’s engaged, that Englishman.”

“Which he neglected to tell you as he was leering at your bodice.” Her attributes. She’d used the more delicate word. The woman beside him wasn’t overendowed. Even in her feminine attributes, Lady Joan had a tidy, elegant quality. “That little omission on his part had to hurt.”

She left off patting his knee—a relief, that—and worried a nail. “The announcement was in this morning’s papers. I was an idiot and I panicked.”

Whoever the English Lothario was, he’d upset a good woman, and done it dishonorably. Many a man had stolen a kiss, but not when promised to another, and not by using cold calculation to muddle the lady.

“You were an innocent, and I suspect you still are. Nobody can tell, you know.”

His blunt speech had her sitting up.

“I beg your pardon?” Her tone was curious rather than indignant, and Dante was glad he didn’t know which mincing fop had taken liberties with her.

“Nobody can tell which favors you’ve bestowed on whom. Maybe you kissed him witless; maybe he put his hands where only your husband’s hands ought to go. Maybe he saw treasures no other fellow has seen. If it was only you and he on that darkened balcony or in that unheated parlor, then it’s your word against his regarding what transpired. If he threatens gossip, you threaten some of your own.”

She fingered her lacy cuff, which wasn’t torn exactly, but the drape of the lace was disturbed by the mishap with the snagged buttons. “A lady doesn’t gossip.”

He was in the presence not only of goodness, but innocence. May his daughter grow up to be just like Lady Joan.

“Many ladies seem to do little else but gossip,” he said, “and the gentlemen can be just as bad, because they apply spirits to their wagging tongues.”

He retrieved his arm from around her shoulders, though that did nothing to take her delicate, feminine scent from his nose, or the warmth of her along his side from his awareness.

“What sort of gossip would a lady bent on revenge start?”

He liked that for all her soft, velvety elegance, she’d ask such a thing, and he liked more that she’d ask him.

“His charming young lordship can’t kiss worth a damn. He gambles indiscriminately. He’s hands are clammy, his breath stinks.” Because the damned fool fellow had it coming, Dante added, “He makes odd noises.”

Auburn brows flew up. “How ever did you guess? He makes whiny little moans, and it’s distracting, and not very manly, the same sounds his lapdog makes when in urgent need of the garden. I’d forgotten his moaning.”

Oh, Dante liked this woman. He liked her very well.

“If he has a lapdog, you’re well rid of him.” The blighter probably had a tiny pizzle, too. If Dante told the lady to bruit that about, she’d likely leap from the train.

Though Dante would catch her.

“Perhaps I am well rid of him.” The first hint of a glimmer of a smile tugged at the corners of her mouth. Not a pleasant, social smile, such as she’d bestow on shop clerks and churchyard acquaintances, but a true, warm, merry smile, such as she’d share with a friend. “Perhaps I am well rid of him at that.”

Dante loved that he’d made her smile, loved that she wasn’t as upset as she’d been, and all because he’d spent a few minutes talking with her—and letting her pet his knee.

So he smiled right back.

![]()

Mr. Hartwell was honest, friendly, and kind, which to Joan was a significant improvement over handsome and charming. He also smelled good—of heather and cedar—and he wore the most marvelous merino blends.

Over thighs that put Joan in mind of the mahogany table under the window. Smooth, warm, hard.

Gracious heavens.

“What has you traveling into the mountains at this time of year, Mr. Hartwell?”

His smiled faded but didn’t leave his eyes, suggesting he was permitting Joan to change the subject.

“The same thing that has me getting up most mornings and ruining my eyes with a lot of reports most nights: business.”

“You’re in textiles.” The polite version of the ballroom on dits.

“I’m in trade,” he said, rising. “I’m not ashamed of working for my bread, Lady Joan. I’m responsible for three mills, and they turn out fine products. They do, however, require both management and capital on a regular basis. Capital being money.”

Tiberius was always going on about capital.

“My mother has ensured that I have a thorough grasp of economics, Mr. Hartwell. Your mills also require land and labor, among other things.” Without his bulk beside her, the train car was not quite so cozy, though it was a good deal more proper.

Mr. Hartwell wedged himself into the bench at the small table, looking momentarily puzzled. “Your mama educated you thus?”

Mama was notorious for her financial skills, at least in Polite Society. Mr. Hartwell couldn’t know that.

“She educated all five of her children regarding money, and Papa thoroughly—if quietly—approved.”

To the extent Papa approved of anything.

Mr. Hartwell retrieved his spectacles from his pocket and picked up a sheaf of papers from a stack on the table.

“Do you mind if I read, Lady Joan? When I reach my destination, I will have little time to acquaint myself with these reports, and a successful negotiation always starts with a thorough grasp of the pertinent facts.”

“You’re not traveling for pleasure, then.”

She had withheld specific permission to read, and Mr. Hartwell must have grasped that subtlety. That’s how desperate Joan was to avoid what memories she had of the previous night.

He put the papers down and stared into the middle distance. “Had I any other choice, I’d not make this journey. I’m invited to spend the holidays with acquaintances too wellborn to dirty their hands in trade where anybody might notice, and because they cannot abide the notion I might raise such a topic where polite ears could overhear, I’m enduring the fiction that I’m a guest at a house party.”

House parties could be delightful—though they were usually tedious in the extreme and at least a week longer than necessary to make that point.

“If you’re not a guest, then what are you in truth?”

Bleak humor crossed his features. He took out a plain handkerchief and rubbed at the lenses of his glasses.

“I’m an opportunity.”

A shaft of cold tricked into Joan’s belly. Edward had said something similar about Joan, though the exact words refused to show themselves from the undergrowth of her memories.

“That doesn’t sound very pleasant.”

“It’s business.” He held his spectacles up to the window, as if inspecting for smudges. “I understand that, and they are an opportunity for me. The land can no longer support the aristocracy in the manner they prefer, and trade is a means of diversifying revenue—of making money in more ways than one. I don’t suppose a lady enjoys talk of the shop, though.”

Gracious heavens, Mama would have Mr. Hartwell’s suppositions for dessert. “Diversification requires a greater management effort, though it ideally spreads risk.”

Drat and a half, she ought not to have said that. Pronouncements along those lines—which Joan had heard at the family dinner table since she’d put up her hair—made gentlemen smile as if their baby sister had just recited a piece of the royal succession—without a single error!

Or the fellows would wince and see somebody else they had to speak with on the other side of the ballroom.

Immediately.

Mr. Hartwell unwedged himself from the banquette and knelt before the parlor stove. “Diversification ideally spreads risk. Explain yourself.”

“Risk has to do with the probabilities and eventualities,” Joan said. “With how likely it is that matters could go awry, or succeed wildly. If you have invested in one solid venture, then your profits are likely to be more reliable than if you invest in two risky ventures. Over time, however, one of the risky ventures might do quite well.”

Risky ventures could also, however, see a lady precipitously ruined.

He added coal to the fire, closed the stove door, and dusted his hands, but remained kneeling, as if he could watch the flames dance through the cast iron.

“I do not believe I have ever heard another female use the word probability regarding anything other than a marriage proposal.”

The greatest risk of all. Joan tucked her feet up under her and came to two conclusions.

Mr. Hartwell had noticed that she might be cold, and rather than ring for the porter to tend to the stove, he’d seen to it himself. Trains were messy and smelly, even as far from the engines as this car was, and yet, Mr. Hartwell had dirtied his hands without a second thought. This suggested he was heedless of strict decorum, but not of the consideration due a guest.

The second conclusion was that Joan’s lapse into territory through which Mama gamboled with heedless abandon had not put Mr. Hartwell off, but rather, had interested him.

“You have the right of it,” he said, rising lithely and bracing himself on the narrow mantel over the stove. Somebody had draped pine swags from the mantel in another nod to the approaching holidays—or possibly in an effort to cut the stench of coal smoke permeating any locomotive. “Diversification can mean greater management effort, so when my betters seek to diversify, they expect me to provide the management, while they reap the profits.”

As if he were a shop clerk, and not owner of the very mill. “You would manage anything in your keeping responsibly.”

He rolled up the pine rope, unhooked it from whatever held it up, and pitched the entire fragrant bundle out the door at the far end of the parlor car.

“How can you assess the management ability of a man you met only weeks ago, Lady Joan? I was born in a dirt-floor croft. I married for money, and I’m known to pinch a penny until it screams for mercy, hence the frequent references to me as Hard-Hearted Hartwell.”

Mr. Hartwell propounded these notions as if they were facts, while Joan suspected they were mostly myths—though a dirt floor was hard to argue with.

“I have witnessed you with your children, Mr. Hartwell. I’ve watched you stack your sister’s trunks. I’ve seen you eyeing those reports as if they were sirens calling you ever closer when I know you need a nap.”

She had also danced with him. Any matter put into his care had his undivided attention.

“I’ll not argue about the nap, but soon the children will be underfoot again, and they tend to frown on Hector’s reports.”

Joan wasn’t too fond of Hector’s reports, and she’d never met this Hector fellow. “Have your nap,” she said, rising. “I had mine, and if you’re headed for a house party, you will need your rest.”

When she might have put her hand on the doorknob, he stopped her by reaching it first. “While you do what?”

He really had no notion of polite discourse. Joan’s chin came up, rather than admit she might have liked a peek at those reports.

“I will explain diversification to your children.”

“How?”

Yes, how? “The holidays are approaching, Mr. Hartwell. I can put it in terms of holiday gifts. Would they rather have one large gift or four smaller ones, any one of which might hold their heart’s desire?”

“Charlie’s heart’s desire is a pet.”

“And Phillip’s?”

Mr. Hartwell studied Joan, which was a lovely opportunity to study him. He was a man in his prime, not a boy. The architecture of his jaw put her in mind of Arthur’s Seat, a geological formation overlooking Edinburgh. The cast of his face wasn’t stubborn so much as ageless. Enduring. His looks wouldn’t change appreciably for decades, and already, his children bore the stamp of his features.

“Phillip wants a baby brother to boss around. The boy is a born manager.”

“A baby—?” He was teasing her, the wretch. Joan patted his cheek, which was rather like patting the surface of the stove—warm and unyielding. “There’s always next Christmas, Mr. Hartwell, particularly for those who are well behaved.”

As Joan had not been.

Somebody ought to have been blushing and stammering—Joan suspected it was she—but instead, two people were smiling. Two adults.

Joan slipped through the door, her smile fading as the cold, smoky air assailed her on the noisy platform.

She had no business teasing Mr. Hartwell like that, no business touching him, no business even sharing a private car with him. For while she might, indeed, discuss diversification with his darling children, most of Joan’s mental efforts should be bent toward trying to recall what, exactly, had transpired in Edward’s parlor the previous evening.

![]()

Dante rooted through the stack of papers until he came up with the report Margs had put together for him. The document read like a book of the Old Testament, one begat after another, followed by was-brother-to, and wed-the-daughter-of.

Aristocrats tended to inbreed, and even line breed, particularly on the Continent. Prince Albert’s father on the occasion of his second marriage, had chosen his niece for his bride, a common undertaking among the pumpernickel princes, for it kept land and wealth in the family.

The English weren’t quite that medieval, but memorizing the intermarriages of the aristocracy was sufficiently narcotic that by the time Dante’s daughter came barreling into the parlor car, his chin was on his chest, and his eyes were closed in…thought.

Marriage was a sort of diversification, or it could be. The titled and wealthy families understood that, as had the clan chiefs of old. The parallel hadn’t occurred to Dante previously, and he didn’t like it.

“Papa!”

“No need to yell, Charlene.” And no need to be fully awake to catch the child up in his arms as she scrambled onto his lap.

“Lady Joan is showing Aunt some fancy stitches. It’s boring.”

Sewing on board a swaying train could not be easy. “Is she stitching up her cuff, then?” The cuff Dante had torn.

“She did that first.” Charlie made herself comfortable on her father’s lap, a conquest simplified by the fact that Dante had folded the table down and propped his feet on the opposite bench. “Why did you take the decorations down, Papa? Christmas is coming!”

Christmas had been coming (!) since Michaelmas, according to Charlie. Shortly after the Yuletide holidays had passed, Easter would approach (!), and May Day, too (!).

“I took them down because anybody who would drape pine swags directly over a burning parlor stove is an idiot.”

“The decorations could catch fire?”

The girl was tempted to suck her thumb, Dante could feel it in her, though she’d never sucked her thumb until her mother had died.

“Almost anything can catch fire.” He took her right hand in his and kissed little knuckles that tasted a touch sticky. “If you could choose between four small Christmas presents and one big one, which one would you choose?”

He asked, because a discussion of fire was not conducive to a small child’s peaceful dreams, and because he enjoyed the way his children’s minds were unburdened by adult preconceptions.

“How small?”

“Smaller than a kitten, larger than a ring.” Charlie cared nothing for rings, yet.

“How big is the big one?”

“You’re gathering your facts, which is smart. The big one is smaller than a pony.”

“Not smaller than a dog?”

Neatly done. “Not smaller than a dog, no.”

“I’d want both. I’ve been very good, though not as good as Phillip. He and Lady Joan were talking about bad things happening or good things happening.”

“They were talking about risk.” Why had Dante never thought to broach such a topic with his small son? The boy would take to the subject with relish—to the extent Phillip did anything with relish.

Dante rose, Charlene affixed to him like a particularly large neckcloth. “Let’s join their discussion, shall we?”

“Aunt said I was to fetch you.”

Well, of course. Because Lady Joan was pretty and single, and Margs was determined to see Dante remarried—Margs was also oblivious to the ironclad rules of Polite Society.

“Then you’ve completed your assignment,” Dante said, making his way from one car to another. The countryside was blanketed in white now, the pines on either side of the tracks bowing branch by branch with a burden of snow. “Pretty out here.”

“Pretty, but cold, Papa.”

A good description of most of the women Dante had met in those fancy ballrooms, though not of Lady Joan. He left the bracing air of the platform for the other parlor car, coming upon a scene of such domestic tranquility, it might have been some cozy sitting room in Edinburgh.

“Ladies.” Dante put Charlie down and bowed slightly, which folly made Margs’s eyes dance. “Charlene said I’d been summoned.”

“Charlene misheard,” Margs replied, all innocence as she bent over her embroidery hoop. “I said it was a shame you had to bury yourself in your reports when we see so little of you.”

Charlie had excellent hearing, also a soft heart.

“Reading on the train is difficult in the best circumstances.” Dante took a place beside his sister on a silly undersized blue sofa bolted to the wall. Clearly, train cars had gender, and the paneled, dark, decantered car he’d left was for the fellows, while this space was for the ladies.

For the back of the sofa curved exactly in the shape of a heart, or of a woman’s breasts at the top of her décolletage.

Phillip, as ever, watched the exchange from across the room without saying a word. The boy had made gathering facts into a life’s work.

“Would you like a chocolate, Mr. Hartwell?” Lady Joan held out a box of sweets, more silliness, but Dante suspected the polite thing to do was to take one.

“Thank you.” Except the blasted confections were nestled among colored paper, so Dante had to dig to extract one—any one at random—and he nearly ended up causing Lady Joan to drop the lot.

“Perhaps I might suggest one?” Lady Joan asked.

Was that how polite people went about such an undertaking? In none of the etiquette books Dante had trudged through had he seen a discourse on the proper method of selecting a chocolate.

He did not want a damned chocolate. He wanted to stand out on the platform until his temper and his cheeks cooled, and then stand out there until his awareness of Lady Joan cooled as well.

Which could well see him frozen before they reached Aberdeen.

“Any one will do.” Because he did not favor sweets, and had said so to more than one titled hostess. He did not say so to Lady Joan.

“No, not just any treat,” she said, peering into the box. “For you, this one, I think.”

In her hand was a treat for which the French probably had a name. Dante took it from her fingers and popped it into his mouth, aware that every other occupant of the car was watching him for a reaction.

“Quite good…quite…” He’d had chocolate before, which came in varying blends of bitter and sweet, much like life. He didn’t care for it, but this was ambrosial. “What is it?”

The flavor was interesting, substantial, appealing, and neither too sweet nor too bitter, and the pungent chocolate balanced whatever the filling was.

“Marzipan,” Lady Joan said. “Mostly ground almonds, some sugar, eggs, a dash of vanilla, that sort of thing. I’m partial to it myself, particularly as the holidays approach. This box was a gift from a family friend.”

She’d treated him to her favorite sweet. Any thought of returning to his reports evaporated, as did a pressing need to make a solitary visit to the frigid platform.

“Shall you join our discussion of risk, Mr. Hartwell? Phillip raised an interesting point, about risk varying with the person taking it.”

“Did he now?” Phillip was a man of a few words, and fewer smiles, and yet, as Lady Joan spoke, the boy beamed at her.

Beamed. When was the last time wee Phillip had beamed?

And why hadn’t his father noticed?

“I have a few opinions on risk,” Dante said as the last of the marzipan melted from his palate.

“We thought you might,” Margs murmured. “About avoiding risk whenever possible.”

His sister was twenty-five years old. She had never, as far as Dante knew, been kissed, and she was lecturing him about avoiding risk.

“I’ll take a prudent risk,” Dante said. “Witness our holiday destination, Sister.”

She might have stuck her tongue out at him, but for Lady Joan’s presence.

“Phillip and I were discussing the risks inherent in a business that depends on women’s fashions,” Joan said, searching with an index finger through the box of chocolates. “Purely as an example of a difficult undertaking.”

“Because women are fickle,” Phillip volunteered, his expression wary.

“Fashion is fickle,” Dante said, though the boy was quoting his own papa. “The textile market is fickle, and competition is fierce. Ladies’ fashions are not a business I’d advise anybody with any sense to go into.”

Lady Joan put the lid back on the box of chocolates and scooted closer to Margs. “Perhaps you’re right, Mr. Hartwell.”

Her tone—and her unwillingness to offer him another treat—said clearly, “And perhaps you’re dead wrong.”

He wished she’d argue with him, and he wished she’d offer him another one of those almond treats—or get her cuff caught, or something.

Stupid wishes. He should have brought his reports along with him from the other car. Instead of studying the slight furrow between Lady Joan’s eyebrows, he might instead have tried—again—to get straight all the interlocking dynastic connections of the prigs and buffoons with whom he’d be spending his holidays.

Chapter Three

Tiberius Flynn, Earl of Spathfoy, loved his countess and his family, though both could try the patience of a damned saint.

“You have that ‘I wish I could use foul language’ look on your face,” his countess said, bussing his cheek.

They were on a train headed for Ballater, and thus Tye’s store of retaliatory kisses was limited.

“How is the boy to learn manly discourse if I never let loose around him?” Tye groused. “Some things a fellow needs to learn by example.”

“Perhaps I should refuse your overtures on occasion, then, hmm?” Lady Spathfoy tucked the blankets up around the baby more snugly, though the child seemed to take to train travel easily enough. “Then you might have had an example for how to refuse Balfour’s invitation to this house party?”

“I could not refuse him. Give me that baby.” Tye plucked the child from his mother’s grasp. “He’s growing too heavy for you to be carting about all the while, and it isn’t as if we’re lacking for nursemaids.”

Both of which had been given leave to stretch their legs, because the train was an hour from Ballater at least.

The other men in the family had warned Spathfoy: once the child started toddling, a papa’s role was sorely limited. The ladies closed ranks about the youngster, as if realizing that once a lad was breeched, the menfolk would have the raising of him forevermore.

Spathfoy’s firstborn son and heir smacked his papa on the chin. “He’ll have a bruising right cross and fierce uppercut.”

Lady Spathfoy—Hester, by name—treated her husband to the gentlest of you-are-ridiculous looks. “I wouldn’t dream of arguing with you, Tiberius. Do you suppose we’ll be the first to arrive?”

She was small, blond, and argued with him brilliantly and often. Her uppercuts were delivered by virtue of embroidered peignoirs, and her bruising right cross was a function of kisses, caresses, and soft asides that rendered a man witless.

Though happily witless.

“I hope we are not the first on the scene. Ian and Augusta promised they’d meet us there, and I cannot imagine my parents lingering in Northumbria when mama might be matchmaking for my sisters.”

May God help them. Joan was racketing about between Paris, London, and Edinburgh, intent on designing fashionable dresses for the women of the aristocracy. The eccentricity of this objective bothered Tye, not because his sister lacked the talent to succeed at such an endeavor, but because Society dealt poorly with eccentricities in an unmarried female. For a man, any hobby, interest, or peculiar start was considered a charming sign of intellect and passion.

While all a lady needed were pretty manners and a fat dowry.

“Balfour House will be damned cold.” Bloody, goddamned cold, though Tye restrained his vocabulary in light of present company.

Her ladyship peered at the baby meaningfully. “Cold sometimes inspires you to great feats of cuddling, Tiberius. Is that baby wet?”

“Very likely.” Train travel inspired infant digestion—another salient fact to which the men of the family had drawn Spathfoy’s attention. “I’ll change him.”

Her ladyship dug more purposefully into the traveling bag, likely to hide her merriment. Tiberius was determined that he should be able to look after the boy in every needful fashion, which even his Scottish relations regarded as a queer start, indeed.

Determination, however, was a familial trait the Flynn’s prided themselves on, and thus—while the results were often lumpy, off-center, or droopy—Tiberius honed this aspect of his nursery maid’s skills on the rare opportunities to do so that came his way.

He laid the child on the bench of their first-class compartment, while his wife studied the frigid scenery of Deeside as it swayed past outside the window.

“Do you know who will join us for this holiday house party, Tiberius?”

Tye let the question wait—a wiggling child, a wet nappy, and a dry replacement required concentration. “Family, mostly.”

“You’re getting better at that,” his wife observed.

“Quicker.” Though the results exhibited a damnable lack of symmetry. Tye tucked the child’s dress down and folded the plush, cream-colored blanket about him. The hem was a riot of leaping, rolling, bounding rabbits—Joan’s work, no doubt—while the blanket itself was the softest wool Tye could recall touching.

“Dora and Mary Ellen will come with your parents, won’t they?”

Tye picked the child up and held him at arm’s length, blankets and all. “Kicking and screaming, but even my sisters wouldn’t abandon Joan to the heathen Scots in the dead of winter.” Much less to Mama’s tender machinations.

Next he hoisted the baby over his head, which provoked the boy to smiling hugely and waving his fists.

“Gahg!”

Both parents stared for a moment at the prodigy who’d uttered this pronouncement.

“Gahg-gaa!”

So of course, the next five minutes were spent waving the child about the train car, until Tye’s arms honestly grew a bit tired. “He’ll sleep now.”

“He’ll remain wide awake,” Lady Spathfoy countered. “Do you ever worry about Joan, Tiberius?”

And thus, they came to the real reason her ladyship had shooed the nursemaids off to the parlor car.

“Incessantly. I had envisioned her finding a genteel companion and establishing herself as a fashionable adornment to Paris society, but that hasn’t happened.”

“Gahg-gaa-gaa!”

The viscount—for the baby was the grandson of a marquess, and in the direct line to inherit the title—struck out at his father’s nose this time.

“Enough,” Tye said. “If God meant for little men to fly about train compartments, he would have given papas greater arm strength.”

Her ladyship waited patiently because it suited her, though she could be marvelously impatient under certain circumstances when private with her husband.

“Joan is my sensible sister. I hadn’t foreseen that she’d cause anxiety,” Tye said, putting the baby to his shoulder and rubbing the child’s small back. “She is doomed to fail with her little fashion venture, and it distracts her from finding a husband, another venture at which she does not seem destined for success.”

“Joan’s dresses are striking,” Hester countered loyally. “You’re putting the child to sleep.”

Tiberius slowed his caresses to the boy’s back. “Joan’s dresses are striking on her. That’s not entirely a good thing when men seek agreeable, biddable, retiring qualities in their spouses.”

“They seek broad hips and empty heads,” Hester sniffed. “Most titled men are dense beyond belief when it comes to seeking a marriage partner. Joan is not in the common mode and deserves a man who can appreciate it. Perhaps she’ll find a prospect at this house party.”

No, she would not; not if Tye had anything to say to it.

“Balfour has invited mostly family, but also a few Scots with interests in trade. He’s of a mind to mix business with pleasure, and shift some of the earldom’s investments from shipping to local ventures.”

The child let out a sigh so great as to shake his entire body.

“That’s it, then,” Hester said. “He’s down for the nonce. The maids won’t thank you.”

Tye would not admit it, even to his wife, but the pleasure of holding the sleeping child was worth all the dark looks and longsuffering mutterings of the nursery crew.

“Joan should have found somebody by now in London, Paris, or Edinburgh,” Tye said, leaning back so he could wrap an arm around his petite countess. “If she can’t snag some prancing dukeling or German prince, then I’ll not have her yoked to a cit with more money than manners.”

Hester nestled against her husband in a most agreeable fashion. “I am the mere daughter of a baron, Tiberius. I would caution you against such rigid expressions of fraternal concern.”

“I do not want to see my sister hurt,” Tye said against his wife’s hair. She was blond, a surprising contrast to her big dark husband, and she always felt just right in his arms. “If one of Balfour’s upstart business prospects thinks to entice Joan to the altar in a weak moment, I’ll soon have him thinking otherwise.”

The countess rubbed her cheek against her husband’s shoulder and closed her eyes.

![]()

A foul, foul stench pervaded Edward Valmonte’s awareness, more foul than usual the morning after his lordship had overindulged.

“Go away,” Edward muttered at the source of the odor.

Campbell yipped, which happy sound ricocheted around in Edward’s head like so many stray bullets. Waking up to hot, smelly terrier breath ought to number among the biblical plagues.

“I said”—Edward rolled over to bury his face in clean linen—“get the hell away from me.”

Another yip, which bore a warning quality.

“I don’t care how deep the snow is. If you tee-tee on Mama’s carpets again, she will have you made into a fricassee.”

After she’d done worse to her firstborn son. The woman had no sense of her proper place in the scheme of things. Campbell was mostly a very good fellow, much like Edward.

“Yip! Yip!” The dratted pestilence followed up with enthusiastic licking about Edward’s ear, which made Edward smile and rather put him in mind of Lady Joan’s breathy—

“Shite.” The worst curse Edward could manage under his mother’s roof, and still inadequate for the combination of woe and queasiness that welled up from within. “Shite and dog breath and tee-tee in the front hall.” He sat up, cradling the dog to his chest. “I am in such trouble. Fricassee will be too good for me.”

The outer door to the adjacent sitting room banged open loudly enough to make Edward wince. One instant too late, Edward understood that Campbell had been trying to alert him to Mama’s approach.

“One hopes you are awake, though Kyle says he has not attended you.” The Viscountess Gilroy’s heels drilled into Edward’s meager store of composure as they clattered against parquet floors. “And”—her ladyship barreled right into Edward’s bedroom—“you had best be up and about, for we’re expected to take tea with Lady Dorcas and her family in light of the day’s developments.”

Mama was no respecter of Edward’s privacy, as if he were still a boy in dresses.

“I’m not decent, your ladyship. You will please allow a fellow a few moments with his valet of a morning.” Against Edward’s chest, Campbell was a warm, reassuring little ball of canine loyalty. He gave a short bark, doubtless agreeing with his master.

“It’s past noon, young man.” Mama’s scolds were all the more effective for being delivered with a hint of a French accent. “And I am sorry to inform you, your lady wife will not take kindly to allowing animals of any description into her bed.”

She clapped her hands, the ultimate insult to Edward’s throbbing head and roiling belly. “Kyle! His lordship has need of you!”

What Edward needed was to apologize to Lady Joan Flynn before the woman’s brother sent his seconds to call.

“Mama, please leave. I must have peace and quiet, a pot or two of black tea, and somebody to take Campbell for a stroll in the mews.”

“I’m here, your ladyship.” Kyle bowed to the viscountess, Edward’s shaving kit in the man’s pudgy hand, a towel over his arm as if he were some damned waiter. “We can be ready in less than an hour.”

We? As if Kyle were Edward’s nanny, getting him ready for an outing to the park.

“Excellent. When you are finished with Edward, you can see to the dog. Lady Dorcas deserves her day to preen and gloat, and of course, his lordship must show himself as her devoted swain.”

Lady Dorcas Bellingham—Lady Dorcas-Rhymes-with-Orcas, according to a zoological wit at Edward’s club—was not a bad sort, though she was prodigiously fond of sweets, and rather an armload to wrestle about on the dance floor. She had an agreeable dimness to her mental faculties, and a nice smile.

“I am not her devoted swain.” Edward fumbled about beneath his pillows for his nightshirt. “Kyle, procure a fellow a pot of tea, if you don’t mind.”

Edward set Campbell down, got a nightshirt more or less on, and mentally prepared himself for the ordeal of standing upright. The bed was elevated two steps for warmth, though what good did warm covers do a man when he broke his neck tumbling from bed in the morning?

“You look positively bilious, Eddie. Were you up late sketching? I must say, those drawings in the sitting rooms are quite the cleverest efforts I’ve seen from you to date.” Mama seemed to look at him for the first time, while Campbell bounded off the bed and turned an encouraging pair of bright black eyes on Edward.

“I was up quite late.” Joan had been sketching—at first—beautiful, flowing, ingenious sketches that provoked Edward to equal parts envy and admiration. And curiously enough, the sketches were apparently still here. “Mama, you really ought not to be in my bedroom.”

“Nonsense. You’ve nothing to display I haven’t seen before. We’ll be stopping by the salon on our way to Lady Dorcas’s, and I cannot afford to indulge your penchant for dawdling. Lady Dorcas could cry off, despite the announcements.”

Edward was focused on navigating the steps, but it didn’t do to ignore Mama’s nattering entirely. “What announcements?”

“Coyness doesn’t become you, Eddie. The announcements of your engagement to Lady Dorcas. Brilliant match, if I do say so myself.”

Edward’s ears began to roar, and his stomach rebelled against his mother’s words, even as his headache escalated to a point past agony.

“I never proposed to Lady Dorcas Bellingham. She and I cannot be engaged.” Though a dim recollection of Mama chattering about productive discussions, and Uncle nodding approvingly suggested Edward’s objection was too little and too late.

Mama regarded him with her head cocked to the side, making her look like a small, puzzled French bird—a bird of prey.

“Don’t be tedious. Bended knee and dramatic declarations are hardly necessary among the better families. The girl has pots of money, and she has the look of an easy breeder. Get dressed, lest we be late for a call on your intended. The announcements went out this very morning, and if we’re quick about it, we can have you married before the New Year.”

Oh, God.

Oh, Joan.

“I’m going to be sick.”

As his mother fled the room in another tattoo of heels, Edward was indeed sick, barely missing her ladyship’s prized Axminster carpets, while Campbell looked on with sympathetic eyes.

![]()