Lady Jenny’s Christmas Portrait

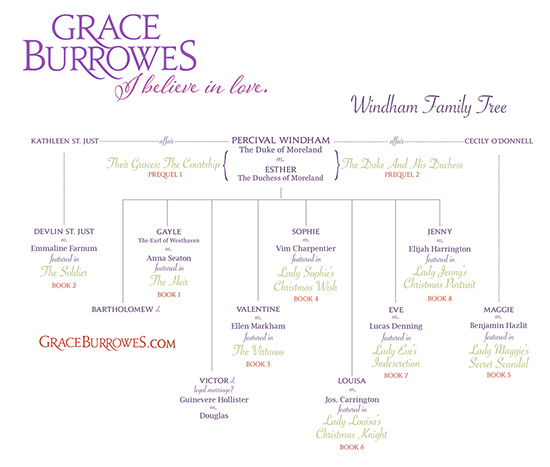

Book 8 in the Windham series

The only unmarried Windham sibling, Lady Jenny would not mind so very much taking care of her parents, if only she could study art in Paris for a few years first. Jenny longs for both an artistic challenge, and for a small taste of the passion life holds for those with the courage to seize it. Lord Elijah Harrington arrives to the Windham household to spend the Yule season painting portraits commissioned by Their Graces, and Jenny thinks she’s met not only a kindred spirit, but a man she might love. Alas, for Jenny—and Elijah—honor has obligated him elsewhere, and while ‘tis the season to be merry, for Jenny and Elijah it will take a miracle to bring them their happily ever after.

Bonus Materials →

Enjoy An Excerpt

Chapter One

Either Lady Genevieve Windham didn’t recognize Elijah Harrison with his clothes on, or she had reserves of self-possession he could only envy.

“Sir, may I be of assistance?” She hovered in the door, a blond angel on a miserable winter night, not welcoming him inside and not refusing him entry—a succinct metaphor for Elijah’s dealings with Polite Society.

“I must beg your hospitality, my lady, for my horse has gone lame, and the weather is worsening. Elijah Harrison, at your service. I left the last posting inn some miles back and have seen no other hostelries along the way.”

He shivered in the wind and sleet and tried not to let his teeth chatter. He was ready for her to refuse him or tell him to go ’round back and seek entry of the cook. The very fingers by which he made his living—and a number of other parts—were long since numb, or he would not have knocked on even this door.

The lady stepped back and gestured him inside. “Gracious heavens, Mr. Harrison, come in this instant. I hope the grooms are seeing to your horse?”

Her green eyes were lit with concern, and not—bless her—for his horse.

“My thanks.” He passed into the warmth and quiet of the Earl of Kesmore’s country house as she closed the door behind him. “When last I saw him, the beast was being led into a cozy stall, his limp improving apace at the prospect of straw bedding and a ration of oats.”

“I’m Jenny Windham,” she said, and that she would eschew her title—as he had eschewed his—caught his curiosity. “The servants are quite done in, today being Stirring Up Sunday. Let me take your coat.”

She hefted the sodden wool from his shoulders and hung it on a hook, spreading the capes and sleeves just so, the better for the garment to dry. This attention to Elijah’s outerwear gave him a moment to study her the way a portrait artist was doomed to study all others of his own species.

Her hands had a competence about them he would not have expected from a duke’s daughter. She dealt with wet fabric as any yeoman’s wife might, then held out a hand for Elijah’s scarf.

“I’ve never seen it rain ice,” she said. “An occasional sleety afternoon, yes, but not this… this”—she grimaced at his scarf—“unending mess. Nobody will be going anywhere if they have any sense. I hope you hadn’t far to go?”

Again the concern in her eyes, and for an uninvited guest who had no business inconveniencing her.

Elijah focused on peeling off damp wool and sopping gloves. “A few more miles yet, but I’m not familiar with the neighborhood, and nothing good ever comes of forcing a lame horse to soldier on.”

“Nothing good at all. You must accept our hospitality tonight, Mr. Harrison. You’ll come with me to the library.”

She did not explain to him that the earl and his countess would be down shortly to welcome him properly, though Elijah well knew this was Joseph Carrington’s house. He would not have presumed to knock otherwise.

And yet he followed Lady Genevieve down a dimly lit corridor without protest, watching the way her carrying candle and the mirrored sconces moved light and shadow across her feminine form. By the time they reached the library, Elijah’s feet were starting the diabolical itching that accompanied a thawing of limbs too long exposed to winter’s wrath.

“You can warm up in here, and we’ll have a room prepared for you,” Lady Genevieve said as she set her candle on a delicately scrolled chestnut sideboard. When his gaze fell upon an embroidery hoop left on the sofa, Elijah realized the lady herself had occupied the library earlier.

“You’re burning wood.” The sweet tang of wood smoke blended with other scents—beeswax, cinnamon, and something floral, an altogether lovely olfactory bouquet.

“Lord Kesmore prefers to burn wood, and his home wood is extensive. If you’ll give up those boots, Mr. Harrison, I’ll have somebody take them down to the kitchen for a polishing. Leave it any later, and the bootboy will have gone to bed.”

Stirring Up Sunday saw the plum pudding tucked into its brandy bath. The kitchen had no doubt been a merry place for much of the day, and the help would need to sleep off the results of their exertions.

How he loathed Christmas in its every detail.

“I’ll wrestle my boots off, but please don’t put anybody to any trouble. I would not want to impose on his lordship’s staff unnecessarily.”

He did not elaborate, leaving her another opportunity to explain that his lordship wouldn’t find it any imposition, and would be told immediately of his visitor.

“I’ll see to some sustenance for you, Mr. Harrison. Please make yourself comfortable.”

She bobbed a curtsy; he bowed. The moment she left the room, Elijah picked up the embroidery hoop to study the gossamer-fine chemise it held. The itching was climbing from his feet to his calves, and would soon overtake his thighs, but he’d seen such needlework only on his mother’s very own hoop, and the artist in him had long grown used to ignoring all manner of bodily inconveniences and urges.

![]()

Jenny returned from the kitchen to find her guest standing before the fire in his stocking feet and shirtsleeves, her embroidery hoop in his hands.

Which would not do. It would not do at all.

“Come eat, Mr. Harrison. I gather the making of the plum pudding occasions something of a celebration among the staff, and so the larder boasted impressive offerings. They’ll be decorating the house tomorrow in anticipation of the Yule season.”

His dark brows lowered and, more importantly, he set her embroidery hoop on the mantel. “I apologize for my state of undress, but my coat was damp.”

Said coat—more sopping than damp—was now draped over the back of a chair set close to the fire, steam rising from the fabric.

Which accounted for the wet-wool scent accompanying the cozier fragrances wafting through the library. Jenny set the tray on the low table before the hearth just as the eight-day clock in the hallway chimed the hour.

“Don’t stand on ceremony, Mr. Harrison. You must be famished.”

And as for his state of undress… Jenny knew firsthand that for all his height, he was lean and hard, every muscle and sinew in evidence when he was naked. Every rib, every pale blue vein, every dark, curling hair on his chest… and elsewhere.

“May I pour for you, sir?”

“Please.”

She took a place on the sofa while he remained standing, which reminded her that whatever else was true about Mr. Elijah Harrison, he had the manners of a gentleman. “You must sit, or you will get crumbs all over the countess’s carpet, and she will not be pleased.”

He came down on the sofa, making the cushions bounce and shift with his weight. “I gather mine host and his countess have already retired?”

A maiden-aunt-in-training ought to expect such questions.

“I would not know. They are from home, and I am keeping my nieces company in their absence. How do you take your tea?”

He was given to silences, which Jenny should have expected from a man who painted for a living. Some artists were so mentally busy trafficking in images that words came to them only reluctantly—a sorry, second-rate form of communication.

“Lady Genevieve, if I know we are without chaperonage, then I will mount my lame horse and find other accommodations. I account Kesmore among my few friends and would not want to give him offense.”

To go with his beautiful body and his beautiful hands, he had a beautiful, masculine voice. She could have listened to that voice recite Scripture and still pictured him without his clothes.

“My aunt is abed on the next floor up.” She paused midreach for the teapot. “You used my title.”

His mouth didn’t shift, but something in his eyes suggested humor. “I make a habit out of attending many of the London social functions. Because I must work in all available daylight hours, I spend most of my evenings dozing in the card room. Even so, I have observed you often from a polite distance.”

Something about the way he used the word observed had Jenny fussing with the tea things. She was rattled by his disclosure, so rattled she fixed her own cup of tea first, with both sugar and cream.

Did he know she’d observed him as well, for hours, when he’d worn nothing but indolence and an offhand sensuality?

“You are prescient,” he said, lifting the full cup. “You know how I like my tea.”

The humor had found its way to his voice, which made Jenny curious to see what a smile would look like on that full, solemn mouth. For all the parts of him she had seen, she had never seen him smile.

“A lucky guess,” she said. “Just as finding your way to Kesmore’s doorstep tonight must have been good luck for you.”

“And for my horse.” He saluted with his teacup, his fingers red with returning circulation.

“Eat something.” Jenny passed him an empty plate. “Chasing the chill from your room will take some time, and you have to be hungry.”

As he filled a plate with as much buttered bread, ham, and cheddar as any one of Jenny’s brothers might have consumed at a sitting, Jenny indulged in closer study of her guest. His dark hair was damp, and around his eyes, fine lines gave him a world-weary air. He was not a boy, hadn’t been a boy for years.

She’d had particular occasion to admire his nose. The nose on Elijah Harrison’s face announced that no compromises would be made easily by its owner, no goal casually cast aside for costing too much effort. Had she not seen the entire rest of him, she would have chosen that nose as his best feature.

He paused between assembling his meal and consuming it. “You’re not eating with me, Lady Genevieve?”

He’d said her name with a little glide on the initial G—“Shenevieve”—the way a Frenchman might have said it. He had studied in France. Somehow, despite the Corsican’s protracted nonsense, Elijah Harrison had managed to study in France. She envied him this to a point approaching bitterness. “I’ll nibble some cheese.”

“Like a starving mouse?”

“Like a woman who had a decent meal not that long ago.” Like a woman who knew it was time to have done with visually devouring her guest. “What brings you to our neighborhood, Mr. Harrison?”

“Work, of course. Some sentimental old fellow has taken it into his head—or perhaps his lady wife has taken it into her head—to have portraits done of his youngest progeny. If I’m to present myself to the world as a well-rounded portraitist, then I must add children to the subjects in my portfolio.”

He said this as if painting children was an occupational hazard, like napping in card rooms.

“Is it difficult to paint children?” Between one heartbeat and the next, Jenny realized Elijah Harrison knew a great deal that she wished she could learn from him. He’d travel on in the morning, but for as much as the next hour, she could interrogate him to her heart’s content.

He didn’t answer immediately. Instead, he put bread, cheese, and some apple slices on a plate and held it out to her. His gaze held a challenge.

Over a simple meal? Abruptly, Jenny wondered if he’d recognized her.

She took the plate and tossed her list of questions aside.

![]()

Genevieve Windham was not pretty, she was exquisite.

Pretty in present English parlance meant blond hair and blue eyes, regular features, and a willingness to spend significant sums at the modiste of the hour.

Unless a woman was emaciated or obese, her figure mattered little, there being corsets, padding, and other devices available to augment the Creator’s handiwork. Failing those artifices, one resorted to the good offices of the portraitist, who could at least render a lady’s likeness pretty even if the lady herself were not.

Lady Jenny left pretty sitting on its arse in the mud several leagues back. Her eyes were a luminous, emerald green, not blue. Her hair was gold, not blond. Her figure surpassed the willowy lines preferred by Polite Society and veered off into the realms of sirens, houris, and dreams a grown man didn’t admit aloud lest he imperil his dignity.

The itching over Elijah’s body faded in the face of the itch he felt to sketch her.

She had certainly sketched him, after all.

“Have some sustenance, my lady. For me to eat alone would be rude, and I intend to consume a deal of food.”

Lady Jenny took the plate, and though he was ravenous, he wanted to watch her eat more than he wanted to fill his belly. “My thanks, sir.”

So… small talk. His livelihood depended as much on his ability to make small talk as it did on his talent for slapping paint onto canvas. “How fare my lord and lady Kesmore?”

“When did you first know you wanted to paint portraits?”

They’d spoken at the same time, though he’d put his question to her, and she’d directed hers to the plate of gingerbread on the tray. Elijah added a slice to her meal and waited.

“Lord and Lady Kesmore are in good health and wonderful spirits. They look forward to the holidays, as do their children.”

Not an answer, but rather, a recitation.

He offered reciprocal superficiality. “I was born with an interest in the arts.”

She glanced over at him, her expression suggesting he was a plate of holiday treats she must not be caught snitching from. “An interest in the arts? A general interest only?”

His answer was the one he gave whenever members of the Royal Academy asked the question Lady Jenny had. The Academy boasted sculptors as well as painters, and one was elevated to membership by vote of the Royal Academicians. A general interest had struck him as the more politic reply.

Lady Jenny was not considering him for membership in the Royal Academy, and would never be in a position to do so.

“Painting has been my preoccupation for as long as I can remember,” he said. “When the other lads were clamoring for a pony or playing Robinson Crusoe or longing to explore darkest Africa, all I wanted to do was paint.”

In some regards, he would have been better off in darkest Africa. Rather than ponder that unhappy truth, he popped a bite of gingerbread in his mouth.

“And where did you study, Mr. Harrison?”

This mattered to her, or mattered more than ham, cheese, gingerbread, apples, and hot tea. “Might I prevail upon you to pour again, my lady?” Because he’d downed his tea in a one hot, indecorous gulp.

“Of course.”

“I studied here and there. I have French cousins on my mother’s side, and while Paris was no fit destination for an Englishman for quite some time, my cousins sought refuge in Italy, Denmark, and Switzerland. I made a royal progress of visiting them and their drawing masters. My mother spoke French to me from the cradle, so France was not as risky for me as it would have been for others.”

Her Exquisite Ladyship fixed his second cup of tea, while he forgot his meal and instead focused on how firelight reflected off the tea service and off her hair. Lady Jenny was not a woman of angles; she was a woman of curves—an elegant curve to her spine in particular suggesting she’d eschewed stays due to the lateness of the hour, or perhaps—being in the country—she had settled for stays without boning.

The teapot was not the tall, silver, decorative variety, but rather, a round, porcelain confection with pink roses and green vines twining about the glaze. The curve of the pottery spout mirrored the curve of Lady Jenny’s neck and shoulder. The green of the leaves was only a shade lighter than her eyes, and the gold tracing on the teacups a near match for her hair. If he were painting her, he’d find ways to echo the lines and colors, in the pattern of the curtains, the curl of a cat’s tail, the foliage of some lush, flowering houseplant or—

“Your tea, and I can find you a book to take upstairs with you tonight.”

She passed him the cup and saucer and decamped for the rows of shelves at the other end of the room.

Being a gentleman, he couldn’t very well remain on the sofa if she wanted to wander the room, despite the fact that he was damp, hungry, and exhausted. He followed her between two rows of shelves, bringing a candle with him.

“You’ll need some light, unless you have Kesmore’s library memorized?”

She didn’t take the candle, so he held it higher, the better to illuminate books, titles, and one lovely, if shy, woman. “One could not memorize the contents of Joseph and Louisa’s library. They’re always acquiring more books, lending this volume, trading that. Louisa is mad for books, and Joseph is mad for his lady.”

“Their collection is to be envied,” he said, studying the titles at eye level. Elijah’s estimation of Kesmore rose—or perhaps widened—as he regarded the spine of an illustrated translation of the Kama Sutra. Beside that was some French erotic poetry, and beside that—

Lady Jenny was not as tall as he’d first thought her. The titles he regarded would not have been visible to her.

Mentally, he shook his imagination by the scruff of its shaggy neck and wagged a finger in its panting, eager face: small talk. “I enjoy Wordsworth.” As a soporific, anyway.

“His poetry is lovely. I’m partial to—”

She fell silent as the library door clicked open, followed by the rapid patter of what sounded like small feet.

“Let’s be quick, Manda. Papa always keeps it in his desk for when we rescue him from the ledgers.”

“Hush, Fleur.” The little feet crossed the library. “If Aunt Jen finds us, she’ll be disappointed in us.”

“I hate when she’s disappointed in us.”

Lady Jenny started forward, clearly ready to rain down disappointment in torrents, but Elijah caught her with an arm around her waist.

“Wait.” Whispering in the lady’s ear meant he had to bend close, close enough to catch the light, lovely scent of jasmine.

She turned her head to whisper back. “They should have been in bed hours ago. Let me go.”

The sound of a drawer opening carried across the room. Through the stacks of books, Elijah saw two small girls, both dark haired like Kesmore, both swathed in thick flannel dressing gowns. They plundered their father’s desk, intent on some mischief.

“Aunt Jen won’t be mad when we draw the pictures. She’ll help us with them and make them ever so much prettier.” This came from the smaller of the two, Fleur. “And Papa won’t be mad when he opens our present.”

“Mama can help us make it into a book, just like her books.”

Against Elijah’s body, Lady Jenny felt as if she were quivering with a need to herd these juvenile felons back to the nursery, while Elijah quivered with something else entirely.

Her scent was marvelous; her curves were marvelous; her focus on the children and complete lack of awareness of him was not marvelous at all, though it was exactly what he deserved.

“Which is your favorite?” Amanda asked as they closed the drawer.

“I like them all. I wonder which is Papa’s favorite?”

Elijah’s favorite was the manner in which Jenny Windham’s backside fit exactly against the tops of his thighs, though the way she’d gone still and relaxed against him made a close second.

“Probably the one about the crow who fills the pitcher of water with stones. Papa likes cleverness and not giving up. Per… Per-something.”

They trundled out, discussing the moral merits of various of Aesop’s Fables, while Elijah realized he’d been trapping his hostess against his damp self for far longer than was wise.

He let her go and retrieved the candle from the shelf where he’d perched it.

“Those are your nieces?”

For a moment, Lady Jenny remained with her back to him. When he should have been plucking a book from one of the lower shelves, Elijah instead studied her perfect, downy nape.

And was still studying it when she turned. “Amanda and Fleur are Joseph’s daughters from his first marriage, though Louisa dotes on them shamelessly, and they love her dearly.”

“And Kesmore dotes on the lot of them.”

He ought not to have said that, because all this doting and loving among Kesmore’s brood put hurt in Lady Jenny’s eyes.

“He does. And the baby. They all adore that infant. We all do.”

She blinked, as if taken aback by the forlorn quality in her own voice.

Elijah slipped past her with the candle, took her hand, and led her away from the shadows and all that intriguing erotica, back to the warmth of the fireplace. “The holidays make everything worse, don’t they?”

She tugged her hand free and looked at him as if he’d recently escaped Bedlam. “I beg your pardon?”

“I beg your pardon. I am tired, and I have not yet done justice to all this scrumptious fare. I was asking if the holidays made being around family particularly difficult, but you will ignore this question. Tell me why Lord Kesmore’s offspring think you will abet their Christmas schemes?”

![]()

Elijah Harrison was like a horse. His body mass was so great, the heat of it would dry out a damp blanket from the inside. He had the sleek musculature of a horse as well, all too evident beneath his damp shirt and breeches.

Jenny stopped herself from drawing any further equine analogies, though held against his body, her back to his chest, at least one more such comparison lurked in her awareness. “Shall we resume our meal?”

“Of course.” He gestured toward the sofa, a gentleman in stocking feet and damp clothing, who posed difficult questions. “I take it you enjoy drawing?”

Very difficult questions. He settled on the sofa beside her, tucking into his food with unabashed enthusiasm, unaware of the havoc he wrought with her composure.

“I do like to draw, and you must like children.”

He paused with a bite of yellow cheese halfway to his mouth. “I don’t think one likes children or dislikes them. One rails against them or surrenders to them, surrender being the more prudent course. Aren’t you going to eat?”

She was hungry—hungry to sketch him, hungry to know what he knew.

“Of course. What did you mean about the holidays making everything worse?”

He paused with a slice of apple in his hand. “I am from a large family, though I’m the oldest, which meant I could get free the soonest. My first objection to the Yuletide holidays is that they fall just as the worst of winter’s weather is getting its grip on the land. Who would position a holiday thus? Travel is difficult; moving goods to the shops for holiday shopping is difficult. Absent gross extravagance, there are no fresh fruits or vegetables to facilitate holiday feasting. All in all, the timing is very poor.”

While he spoke, he gestured with the apple slice, not grandly, but with the languid eloquence of a thoroughly Gallic wrist. He probably shrugged like a Frenchman too.

Jenny took a sip of her tea, but it was tepid and weak compared to the man beside her. “Have you other objections?”

“I do, but I would rather hear about your drawing, Lady Genevieve. Your nieces were convinced you had some skill.”

Some skill. That was all she had—little training, and less hope of acquiring any unless she took very drastic measures indeed.

“I enjoy it.”

He munched the apple slice into oblivion far more tidily than a horse would have and reached for another. “You, my lady, are prevaricating.”

On so many levels. “How do you know?”

“Your eyes. They truly are the window to the soul, and that window closes a little when we dissemble. Most people glance down and left, others—some women—acquire a particularly vapid expression when they lie. You aren’t one of them.”

He held the second apple slice up to her. “Tell me about your sketching.”

Temptation loomed irresistibly. When Jenny had sneaked into Antoine’s classes, she’d loved the time spent immersed in creation, but she’d loved just as much the discussions that followed.

“I dabble, though I love the dabbling. I can sketch for hours, and when I’m not sketching, I want to be painting. If I can’t sketch or paint, then I can embroider. The tedium of the embroidery, the stitch-by-stitch pace of it, can be meditative, but it’s frustrating too.”

The entire time she’d spoken, he’d held the apple slice up before her and kept his gaze on her. Now he took a crunchy bite and held the half remaining before her again, his focus on her mouth.

She wanted to lean forward and take what he offered with her teeth; instead, she took it with her fingers, dodging whatever dare he’d posed.

“You’re still holding back on me,” he said, helping himself to the gingerbread. “You want nothing but to spend your days creating, studying the masters, or reading about their lives and works. You long to travel the Continent, I’m supposing, and feast your eyes on the treasures there—what treasures the Corsican didn’t acquire for himself. Am I right?”

Jenny could not tell if he disapproved of the person he described or was merely familiar with such creatures.

“You have never been so afflicted?”

“I was so afflicted.” He dispatched another crispy apple slice, followed it up with a few bites of ham, then set about buttering a slice of bread. “Inside every professional artist a passionate amateur lies entombed. Enjoy your frustration, my lady.”

The arrogance, condescension, and lurking bitterness of his pronouncement made Jenny want to spit out the apple he’d just shared with her. “Are you mocking me?”

He paused with a dollop of butter on a wooden knife poised above the bread. No, not bread. They’d baked the year’s first batch of stollen today, a holiday sweet bread made according to Jenny’s German grandmother’s recipe.

He set the stollen on her plate. “I am envying you, dear lady. I trust you enjoy butter.”

“Of course.” She did not precisely enjoy his company, though being around him made her feel more… more. “If you’re unhappy with your art, why not give it up?”

The same question she’d asked herself countless times.

“I am not unhappy with my art, and now you are trying to distract me.” His tone was gentle, coaxing, and implacable. “Tell me about your drawing. When did you become interested, and when did you become aware you were different from the other girls?”

Those who sat to him said Elijah Harrison was a comfortable fellow to spend hours with. Jenny had found the notion preposterous. Elijah Harrison was big, quiet, and self-assured. He moved through life with a knowing, confident quality that struck her as incompatible with comfortableness.

She’d come to that conclusion without ever having talked to the man, though, and here, late at night, over informal victuals, his coat gently steaming two yards away, he regarded her with such, such compassion, that she wanted to entrust him with all her silly secrets and dreams.

When she had sketched him, his eyes had been bored, lazy, and slightly mocking: Here I stand, more confident in my nudity than you lot cowering in your fashionable attire behind your sketch pads.

In hindsight, and with the passage of a few years, she had realized that in a room full of young men with varying degrees of artistic talent, he’d adopted that attitude more for their ease than his own.

“Genevieve?”

Shenevieve? She ought to remonstrate him for his presumption, but the sound of her name on his lips was too lovely.

“I’ve always been different. I’m different still. Everything you said… that’s who I want to be. I am a duke’s daughter, though, and probably more significantly, the daughter of a duchess. Were I to give vent to my eccentricities, it would break my parents’ hearts.”

A quantity of food had disappeared, and now Mr. Harrison appeared content to feast on her silly notions. “So you choose instead to break your own heart?”

She left off staring at his hands and rose to tend the fire. His question had not been challenging, but worse—far worse—gently pitying.

“One can love others, Mr. Harrison, or one can love one’s own ambitions. A woman who chooses the latter is not highly regarded in our society. A man who chooses the former is regarded as weak or possessed of a religious vocation.”

He did not pop to his feet when she knelt before the hearth and arranged an oak log on top of the stack already burning. Oak was heavy, though, and the weight of the additional log collapsed the half-burnt ones beneath it, sending a shower of sparks in all directions.

“Careful. Your skirts might catch.”

He’d seized her under the arms and hauled her away from the hearth in one smooth, brute maneuver. When she ought to have been offended or unnerved, Jenny was impressed.

“Thank you. While you finish your meal, I’ll check on your room.”

She left him there by the fire for two reasons. First, she’d offered him quite enough of her confidences for one night and had failed utterly to wring any from him—professional or personal.

The second reason Jenny fled into the cold, dark corridor was that she liked standing close to Elijah Harrison far too much.

Chapter Two

As Elijah accompanied his hostess through the chilly, dimly lit house, fatigue hit him like a runaway freight wagon. This was what came of trying to make a winter’s journey when sane people were holed up with one another, tippling brandy and making gingerbread.

No, not sane people. Sentimental people.

“Your room is here,” Lady Jenny said, opening a door. She led him into a blessedly, gloriously cozy space, into a bit of heaven for a man who’d considered he might end both the day and his life shivering in a snowy ditch.

“Lady Kesmore takes her hospitality seriously,” he said. The appointments were in a cheery blue and cream with green accents—again, not quite the green of Lady Jenny’s eyes—giving the chamber a feminine air even by candlelight. A fat, black cat kitted out as if in formal evening attire—black fur tailcoat and knee breeches; white fur cravat, boots, and gloves—rose from the bed and strolled for the door, tail held high.

When a room was truly clean, light filled it easily. A beam of sunshine or flicker of candlelight could bounce from a sparkling mirror, to a gleaming hardwood floor, to a polished lamp chimney or sconce mirror.

The room was very clean, and in the hearth, a wood fire crackled merrily.

“I have never regarded the scent of wood smoke as a fragrance,” he said, “though tonight, I certainly do.”

“You were quite cold, weren’t you?” she asked, lighting the candles by his bedside tables. “I forgot to get you a book.”

“I would not read a single paragraph before succumbing to the charms of Morpheus.” Where, if God were merciful, Elijah would dream of Lady Jenny illuminated by candlelight.

Another scent came to him as she moved around the room, a light, spicy perfume that started off with jasmine and ended with feminine mysteries.

“I’ll have one of Lord Kesmore’s dressing gowns brought to you,” she said, peering into the pitcher on the hearth. “A footman remains on duty at the end of the hall until midnight, and then we rely on the porter through the night.”

“I’m sure I won’t waken in the night, and I might have to be roused to break my fast as well.”

Small talk. She ought not to be in this room with him, though for present purposes, she was his hostess and had left the door a few inches ajar as a nod to propriety.

“I’ll bid you pleasant dreams, then.” She bobbed a curtsy and withdrew, leaving Elijah alone in his heaven.

Somebody had brought his things in from the stable and set his bag on the chest at the foot of the bed. Lest his worldly goods rot by morning, Elijah took out each damp, wrinkled article of clothing and draped it over the furniture, making sure at least a clean shirt and cravat were in proximity to the fire. As he saw to his wardrobe, he munched on one of the three pieces of gingerbread he’d filched from his supper.

The last order of business on this difficult and interesting day was to wash off before climbing into the fluffy blue-and cream-wonder that was his bed. He peeled his damp shirt and waistcoat from his body, hung them from the open doors of the wardrobe, and set about using the water left considerately near the hearth.

The water was scented with something bracing—lavender and rosemary?—and was small compensation for the lack of a steaming hot bath. Elijah had just finished with his ablutions when a knock sounded on his door.

That would be the footman with a nice, cozy dressing gown, no doubt, courtesy of the absent Lord Kesmore. “Come in.”

“I’ve brought—”

Lady Jenny closed the door behind her and stood across the room, clutching a green velvet dressing robe that would probably wrap around her three times.

“My dressing gown.”

He’d long since grown comfortable sporting about in the altogether for inspection by others, provided the surrounds were comfortably warm. Around Genevieve Windham, his state of partial undress slammed into him like two freight wagons galloping at each other from opposite directions.

The practical part of him spoke up: She’s seen you in less than this. You’re exhausted. Take the bloody dressing gown and bid her goodnight.

But that sensible, familiar voice could barely be heard for the greater din created by what he saw in her gaze.

She was visually consuming him, taking in every muscle and sinew, cataloguing joints and textures even as she clutched the dressing gown to her like a shield.

“Were I modeling,” he said as he approached her, “my exposed skin would probably be oiled, or, when needs must, coated with butter, the better to catch the light, particularly if the scene depicted is dark. I apologize for the lack of attire, my lady.”

He tugged on the dressing gown. She didn’t give it up.

“What kind of oil?”

“I prefer…” His brain became befogged with… her. Yes, he wanted to sketch her, wanted to unearth all the artistic and female confidences she’d denied him, but he also wanted her to sketch him.

Though he’d have to keep his breeches on.

Bid her good night.

“What kind of oil?” she asked again.

“Fragrant, soothing scents.” Jasmine appealed strongly. “When one must hold the same position for a length of time, the more relaxed one is, the more successful the exercise.”

She ought to tell him she hadn’t known he modeled—small talk relied heavily on polite untruths—and then he could tell her he hadn’t provided that service to anybody for years, which was not an untruth. He no longer needed the money, and he no longer had the time.

More to the point, the woman ought to be running from the room in high dudgeon or at least sporting a furious blush.

Lady Jenny handed over the dressing gown and watched him shrug into it with something like grief in her eyes.

“My lady, I bid you goodnight, and my compliments to Kesmore on the quality of his wardrobe.” The garment was lined with silk, and yet, Elijah wanted to drop it to the floor so Lady Jenny might continue to regard him so ravenously.

“Will you model for me, Mr. Harrison?”

She might have challenged him to a duel, so fiercely had she thrown down the question. He’d once had the same kind of determination, willing to travel through war zones to see an obscure Caravaggio.

“My lady, you flatter me, but my journey will take me away…” No true gentleman would have obliged her request. No true artist who understood the limitations of her station and the relentless clamoring of her artistic inclination would refuse her. Among all the dilettantes and dabblers to pass through old Antoine’s studios, Lady Jenny was one of few students to possess a germ of real talent.

“You said you had only a few more miles to go, Mr. Harrison. Give me half an hour in the morning—the nursery has excellent light, being at the top of the house.”

“I cannot be private with you when I am en dishabille.” He should not be private with her when in a coma, and they both knew it.

“I did not expect that you would be. Fleur and Amanda would find it most curious were you to appear unclothed. After breakfast, then?”

The prospect of traveling even a few more miles in miserable weather had no appeal, and she’d taken him in when he might have perished for his stubbornness. Then, too, given how fiercely she’d regarded Kesmore’s daughters, Lady Jenny wouldn’t be focusing for long on a sketch when the children were underfoot.

“A half hour then. My thanks for the dressing gown.”

She left, and this time didn’t bother with a curtsy, nor he with a bow. He ran the warmer over the sheets then hung the sumptuous dressing gown in the wardrobe, where the scent of jasmine was even stronger.

When he laid down on the lovely warm sheets, the same fragrance assailed him.

Elijah’s last waking thought was that Lady Genevieve had given up her bed for him and taken a colder, more humble chamber elsewhere in the house. This eased his last, lingering hesitance about giving her a half hour of his time in the nursery.

A half hour lounging about in the morning sun was small recompense to the lady who’d provided a virtual stranger food, clothing, shelter, and a night surrounded by her fragrance.

![]()

While tossing and turning in a strange bed, Jenny had given considerable thought to which part of Elijah Harrison she’d capture for her own on paper. His hands appealed—his big, elegant, so talented hands. With those hands, he’d done a portrait of the regent even Prinny himself was said to like. She considered those hands as Fleur and Amanda galloped around the hearth rug in the nursery.

“And where shall you pose me, my lady?” Mr. Harrison asked.

Jenny glanced at the eight-day clock in the corner of the nursery. He’d be leaving soon…

“Will you pose me too?” Amanda asked.

“And me,” Fleur chorused. The girls turned big, beseeching eyes on Jenny, eyes that promised best behavior for at least five entire—though not consecutive—minutes. The nursery maids had decamped for a spot of tea, which Jenny suspected would be chased with a headache powder or two.

“In the light,” Jenny said, taking Mr. Harrison by the arm and directing him to a rocking chair by the windows. “Amanda, can you fetch your sketch pad, and, Fleur, yours too?”

They thundered off, while Jenny regarded her subject. “I’m going to focus on your hands, Mr. Harrison. Hands can be complicated.”

He smiled as if she’d just explained to the Archbishop of Canterbury that Christmas often fell on the twenty-fifth of December.

“I like hands,” he said, taking his seat. “They can be windows to the soul too. What shall I do with these hands you intend to immortalize?”

She hadn’t thought that far ahead, it being sufficient challenge to choose a single aspect of him to sketch. Fleur and Amanda came skipping back into the room, each clutching a sketch pad.

“You will sketch the girls, and I will sketch you, while the girls sketch whomever they please.” The plan was brilliant; everybody had an assigned task.

Amanda’s little brows drew down. “I want to watch Mr. Harrison. Fleur can sketch you, Aunt Jen. You have to sit very still, though.”

“An unbroken chain of artistic indulgence,” Mr. Harrison said, accepting a sketch pad and pencil from Fleur. “Miss Fleur, please seat yourself on the hearth, though you might want a pillow to make the ordeal more comfortable.”

Amanda grabbed two burgundy brocade pillows off the settee, tossed one at Fleur, and dropped the other beside Elijah’s rocker. Jenny took the second rocking chair and flipped open her sketch pad.

Her subject sat with the morning sun slanting over his shoulder, one knee crossed over the other, the sketch pad on his lap. Amanda watched from where she knelt at his elbow, and Fleur…

Fleur crossed one knee over the other—an unladylike pose, but effective for balancing a sketch pad—and glowered at Jenny as if to will Jenny’s image onto the page by visual imperative.

“Your sister has beautiful eyebrows,” Mr. Harrison said to his audience. “They have the most graceful curve. It’s a family trait, I believe.”

Amanda crouched closer. “Does that mean I have them too?”

He glanced over at her, his expression utterly serious. “You do, though yours are a touch more dramatic. When you make your bows, gentlemen will write sonnets to the Carrington sisters’ eyebrows.”

“Papa’s horse is Sonnet. Tell me some more.”

While he spoke, his pencil moved over the page in short, light bursts of activity. “Notice the way Miss Fleur’s eyes, as beautiful as they are, aren’t pitched at exactly the same angle. Nobody’s face is perfectly symmetrical, not if you study them closely.”

“What’s symmet—that word you said?”

While Jenny sketched, and Fleur sat a little taller on her burgundy pillow, Mr. Harrison provided Amanda a concise, understandable explanation for symmetry, then went on and described the ways asymmetry made an image interesting.

“Have you ever drawn a crow?” Amanda asked. “Or a pitcher?”

“I’m sure I have. Crows are a challenge because they want you to think they’re black, but in the sun, they’re many colors.”

From across the room, Jenny saw her nieces consider crows in a whole new manner, not as rough-voiced avian nuisances, but as peacocks in disguise.

“So what do you do when you want to draw a crow?” Amanda’s nose was less than inch from Mr. Harrison’s sleeve.

His pencil did not stop moving, though Fleur was beginning to fidget now that her soon-to-be-legendary eyebrows were no longer under discussion.

“I try to draw the crow as he sees himself. They’re curious fellows, flying about as if the entire world were available as their perch. I’ve seen a crow light on the back of a cow, for example, and the cow had nothing to say to it.”

Amanda grinned, a child who might like to fly through the clouds and light on the back of a cow.

“I’m curious too,” Fleur said. “I don’t want to sit on a cow. I want to sit on a pony.”

“What would you name your pony?” Mr. Harrison asked.

Jenny listened with half an ear to the earnest and protracted discussion that ensued. Naming a pony was apparently a holy undertaking in the opinion of her nieces, but then, their father was a former cavalry officer.

As Jenny’s father was. Her pencil stopped moving, as her mind started a roll call of family members who’d served in the cavalry:

His Grace; her uncle Tony; her oldest brother, Devlin St. Just; her brothers-by-marriage, Kesmore and Deene; her late brother, Bartholomew… Thoughts of Bart brought both grief and anger.

And of course, guilt.

The clock chimed the quarter hour, prodding Jenny out of her reverie. Across the room, Elijah Harrison had made two conquests by virtue of simply talking with Fleur and Amanda. He’d glanced over at Jenny occasionally, his gaze amused and patient.

While she had only fourteen more minutes to give vent to years of artistic frustration.

And yet, when she looked down at the page twenty minutes later—Fleur would remain still no longer, not even with a book on her lap—Jenny had not sketched Mr. Harrison’s talented hands, or not just his hands.

“Shall we have a critique session?” he asked as he rose. “I’m sure the young ladies would be happy to assist us.”

His hand settled on Fleur’s dark curls, and the little girl went still beneath his touch. Even Kesmore didn’t have that effect on his daughter, while Jenny felt her insides take flight: a critique session with Elijah Harrison?

“I have used up my half hour and then some, Mr. Harrison. I would not impose further.”

“Nonsense. My model has been very patient, as has my assistant, and I’m sure they’d be fascinated to see what we’ve created.”

“I can show you my sketch,” Fleur volunteered.

“What’s a critique session?” Amanda asked.

A critique session was when you put your heart in the middle of a busy thoroughfare and hoped at least some of the passing traffic didn’t roll directly over it.

Mr. Harrison smiled down at Amanda. “A critique session is when people who share a similar passion try to help each other improve their work. Like when you read your papa’s poetry and suggest a better rhyme to him.”

“Mama does that,” Fleur said. “She makes Papa smile. I know a lot of rhymes. Do you want to see my sketch?”

He held out a hand. “Of course.”

In one gesture and two words, he’d given Fleur a gift of confidence no one would take from her. Jenny envied her niece and understood now why people enjoyed sitting to Elijah Harrison.

He was quiet; he was reserved. He was not the most cheerful individual, and he could be brusque, but he was kind. She had not appreciated this about him when he’d joined in the critique sessions at Antoine’s, though her recollection was of a man who’d offered suggestions and observations, not criticisms.

He appropriated the brocade pillows and arranged them on the hearth, then held out a hand to her. “Come, Lady Jenny. Let us assemble the jury.”

His hand was warm, and he seated her as graciously as if they were at one of the Duchess of Moreland’s entertainments. Fleur and Amanda each tucked themselves against an adult, and Jenny tried to quiet her nerves.

He would not laugh at her work in front of the children, would he?

“Miss Fleur, your work comes first, lest you burst with excitement and rain feathers all over the room.” He took Fleur’s proffered sketch pad and regarded her efforts in silence for some moments.

“You are an honest artist,” he remarked. “You have chosen to present your aunt without even a hint of a smile. That was brave of you, but also accurate, given how hard Lady Jenny concentrates on her art. Lady Jenny, what can you add?”

Jenny took the little sketch, prepared to wax enthusiastic about some lines and squiggles, only to be brought up short.

“Fleur, you have a good eye.” On the page, a lady sat hunched in a rocking chair, the composition a heap of dress, chin, and severe bun, as if crabbed with age. No particular features were evident, and proportion was a lost cause, as was perspective, and yet, the child had managed to catch something of an unhappy intensity about Jenny’s posture. “I’m very impressed.”

“Let me see,” Amanda demanded. She plucked the sketch from Jenny’s hands. “That’s Aunt Jen. She loves to draw.”

Jenny wanted to study Fleur’s childish rendering at greater length, she wanted to draw Mr. Harrison forever, and she wanted him gone from the house.

“Lady Jenny, your turn.”

She passed her sketch pad over to him, feeling a pang of sympathy for accused criminals as they stood in the dock. And yet, she’d asked for this. Gotten together all of her courage to ask for this one moment of artistic communion.

“Well,” Mr. Harrison said, “isn’t he a handsome fellow? What do you think, ladies?”

“You look like a papa,” Fleur observed. “Though our papa doesn’t sketch. He reads stories.”

“And hates his ledgers,” Amanda added. “Is my hair that long in back?”

“Yes,” Jenny said, because she’d drawn not only Elijah Harrison’s hands, but all of him, looking relaxed, elegant, and handsome, with Amanda crouched at his side, fascinated with what he created on the page.

“I look…” He regarded the sketch in silence, while Jenny heard a coach-and-four rumbling toward her vulnerable heart. “I look… a bit tired, slightly rumpled, but quite at home. You are very quick, Lady Genevieve, and quite good.”

Quite good. Like saying a baby was adorable, a young gentleman well mannered.

“The pose was simple,” Jenny said, “the lighting uncomplicated, and the subject…”

“Yes?”

He was one of those men built in perfect proportion. Antoine had spent an entire class wielding a tailor’s measure on Mr. Harrison’s body, comparing his proportions to the Apollo Belvedere, and scoffing at the “mistakes” inherent in Michelangelo’s David.

Jenny wanted to snatch her drawing from his hand. “The subject is conducive to a pleasing image.”

He passed the sketch pad back, but Jenny had the sense that in some way, some not entirely artistic way, she’d displeased him. The disappointment was survivable. Her art had been displeasing men since she’d first neglected her Bible verses to sketch her brothers.

“You next, Mr. Harrison.”

“Of course.” He passed her a charming little study of Fleur perched on the hearth, the tip of her tongue peeking from her lips as she concentrated on sketching Jenny. Something in his portrait reminded Jenny of Fleur’s sketch of her aunt.

“You made her hair tidier,” Amanda noted. “Fleur hardly ever looks that serious, though.”

“One takes a few liberties in the name of diplomacy,” Mr. Harrison said. He aimed a look at Jenny, likely intended to give the words deeper meaning.

He was tired, and he was rumpled. Where was the harm in showing those things?

“He means,” Jenny said in anticipation of Amanda’s question, “that one needn’t show every unflattering detail when trying to render a person’s essence on the page.”

“Like if the crow had some tattered feathers, you’d still try to show how shiny they were?”

“Yes, Amanda,” Mr. Harrison said, though he was looking at Jenny as he spoke.

The nursery maids returned, looking somewhat restored, and Jenny’s half hour—an hour in truth—with Polite Society’s most in-demand portraitist was over.

And in that hour, she had not earned his respect for her art. This should be a relief, should give her ammunition to aim at the part of her that wanted nothing but to disgrace herself with an artistic life, and damn the consequences.

As he escorted her down through the house, Mr. Harrison stopped on the first landing. “Why so quiet, my lady?”

The daughter of a duchess was capable of great feats of diplomacy, also great feats of courage. Jenny would never have an opportunity to work with an instructor of Elijah Harrison’s caliber again, or at least not for many years.

“You did not like my sketch.”

The servants had been busy. In the foyer below, wreaths hung in the windows, cloved oranges in the middle of the wreaths. The scents were lovely and the light cheerful, but the space, being high ceilinged and windowed, was cold.

“I liked your sketch quite well.”

“What did you like about it?” Because in five minutes, he’d be on his horse and disappearing into the winter landscape, and Jenny had to know what he’d seen in her work, even if he’d seen only trite, unprepossessing efforts.

“You are good, Lady Genevieve. Your accuracy is effortless, you’re quick, and your technique very proficient for one who has likely had little professional instruction.”

Those compliments would have distracted her, had she not been watching his eyes. His soul was not in those terse compliments, and he’d be gone in four minutes.

“But?”

He captured her hand and placed it on his arm, moving with her down the last flight of stairs. “But you rendered me tired and rumpled, when I was quite sure the fellow in that nursery was the most charming exponent of English artistry ever to aspire to membership in the Royal Academy. You also made me look…” He glanced around as they gained the empty foyer. “Lonely.”

“Amanda said you looked like a papa. I tried to convey the affection with which you—”

“I miss…” He frowned, unwound his arm from Jenny’s, and stepped back. “I have many younger siblings. It’s natural I should miss them from time to time. That you saw in me something I’d ignored in myself confirms your talent rather than denies it.”

Somewhere in that grudging admission was a true compliment, though likely one he hadn’t intended.

“Thank you.”

Which left nothing more to say. The footmen being derelict or preoccupied with decorating some other part of the house, Jenny took Mr. Harrison’s greatcoat down from the hook and held it up to him. Next she passed him his scarf, then held his hat and gloves while he buttoned up.

And then their time together was over, and Jenny heard the sound of many heavy coaches rumbling, not toward her artistic inclinations, but more in the direction of her heart. “Safe journey, Mr. Harrison.”

“My thanks for your hospitality.” He tapped his hat onto his head and pulled on his gloves. “Have you considered corresponding with old Monsieur Antoine? He’s very generous with his guidance, and not at all opposed to encouraging the talented amateur, regardless of gender.”

His suggestion cut in several ways, though it was intended as another compliment—to a talented amateur of inconvenient feminine persuasion. “Monsieur is, as you say, very generous, but his eyes are failing.”

Mr. Harrison tossed the ends of his scarf over his shoulders in a gesture more Continental than English. “I didn’t know that.”

“Few people do. He has been helpful, though now when I call at his gallery, we spend our conversations on his reminiscences. He’s very proud of you.”

Mr. Harrison glanced up, as if entreating the heavens, then grimaced. “The Yuletide season has officially started.” He pointed to the crossbeam over the antechamber, where a swag of mistletoe had been hung.

“Louisa and Joseph are quite enamored of all things—”

Whatever nonsense Jenny had intended to spout one minute before Elijah Harrison trotted out of her life, she forgot as he put a gloved hand on her shoulder. “It’s a harmless tradition,” he said. “One I’ve had occasion to appreciate.”

With that, he kissed her, and not on the cheek as a proper gentleman ought. He touched his mouth to hers softly, a lingering, gentle kiss that conveyed… something. Regret perhaps, at having to face the miserable winter day.

Before he drew back, he whispered, “You’ll want to look at the sketch book I used, and, Genevieve?”

He bore the scent of rosemary and lavender, and he was leaving.

“Mr. Harrison?”

“You draw wonderfully. Be proud of yourself.” He gave her cheek a quick buss and passed through the door.

Jenny held his compliment close to her heart—the real compliment, the one he’d whispered. She held his kisses closer.

Chapter Three

“Yon beast will not go sound.” Joseph Carrington, Earl of Kesmore, scowled at Elijah’s horse as the gelding was led from the Kesmore stables. “Listen to the footfalls, Harrison. Your hind end is off rhythm.”

And people called artists eccentric.

“Kesmore, good morning. My hind end is traveling down the lane posthaste, though you have my thanks for providing shelter for the night in absentia.”

Kesmore’s frown—the man’s dark features had an entire repertoire of frowns, scowls, glowers, and glares—turned affectionate. “You will forgive my countess for not greeting you here in the yard. She must see to our son’s safe passage up to the house.”

Lady Kesmore, accompanied by a maid, was wending her way from the coach house up a shoveled path toward the manor.

“Congratulations on the birth of an heir,” Elijah said. “I thought you had only the two daughters.”

Kesmore’s affectionate scowl became a long-suffering affectionate scowl. “According to my wife, when the child’s nappies want changing, that boy is my son. When he’s charming every female in the shire, he’s her ladyship’s son. Weren’t you to have immortalized my daughters on canvas at some point?”

He would recall that, and likely recall that Elijah had dodged the commission. Now, Elijah needed juvenile portraits in his portfolio if the Royal Academy was to look favorably upon him, else he wouldn’t be ruralizing away his holidays.

“I apologize for not being here to receive you in person,” Kesmore said as Elijah’s horse was led away. “My lady and I had business in Surrey, and last night we tarried at her sister Sophie’s household rather than push homeward in dirty weather. The womenfolk must disappear into the nursery and exchange maternal intelligence while my brother-in-law and I disappear into his study and say nothing of any consequence beyond, ‘I’ll have one more tot, thank you.’”

“I see.” Marriage had turned the taciturn Kesmore into a chatterbox. The transformation was both disconcerting and… endearing.

“You don’t, but should The Almighty bless you with children, you shall.”

“If The Almighty would see fit to let me get to my next destination without further mishap, I will be most grateful.”

As Kesmore’s wife disappeared into the house, Kesmore resumed his perusal of Elijah. “I trust Lady Jenny made you welcome?”

“Very.” Kesmore’s eyes narrowed, and like an idiot, Elijah babbled on. “She is knowledgeable about art, and her company is enjoyable.” Also a sore trial to his self-restraint, which was why departure this morning was a relief.

Mostly a relief.

The thwack of Kesmore’s riding crop against his boot punctuated the soft whistle of the winter wind. “Lady Jenny can handle the hellions gracing my nursery, which ought to recommend her to half the bachelor princes in Europe. She talks horses with me, poetry with Louisa, politics with His Grace, recipes with—”

Kesmore broke off and waved one black-gloved hand in the direction of the house—a silly wave, hand up, fingers waggling madly. Elijah followed the man’s gaze and saw a woman in a third-floor window with a child in her arms. In a gesture ubiquitous among mothers, she was waving the baby’s tiny hand in Kesmore’s direction.

“The child probably can’t even see you, Kesmore, and he has no notion why you’re fluttering your hand around.”

“Neither do I, and someday, neither will you.” This time Kesmore waved his riding crop at the mother and child, who waved right back. Beside Lady Kesmore, Lady Jenny appeared in the window, a feminine incandescence in an otherwise prosaic tableau.

Elijah did not wave. Not to the baby, not to the baby’s mother, not to his aunt.

“Here comes your noble steed,” Kesmore said. “This is Bacchus. He’s a sensible lad once he gets the fidgets worked out, and he’s not particular about the footing.”

The sensible lad was about the size of an elephant, the same color as an elephant, and possessed of a hair coat worthy of a mastodon. The beast was also making shameless eyes at Kesmore.

“He looks sturdy enough.”

“Much like you, Harrison, he’s a treasure whose subtle gifts can be appreciated only over time. If you’ll excuse me, I’m off to interrogate my sister-in-law regarding the offenses committed by my offspring in my absence. I will take on this thankless burden without my countess’s fortifying presence, while her ladyship tends to obligations in the nursery I am biologically incapable of assisting with.”

This was more married-man-papa blather about Elijah knew not what. To see what a short trip to the altar had done to a decorated veteran of the Peninsular Campaign, a bruising rider, and halfway friend was unnerving.

And yet, Kesmore was… happy. Scowlingly though radiantly happy.

“If you had to choose one of Aesop’s fables as your favorite, Kesmore, which one would it be?”

Kesmore paused midstride toward the manor and turned a puzzled frown on Elijah. “In what regard? A favorite moral, a favorite story? A favorite because the tale is brief and will get my daughters most quickly into bed?”

“Your favorite. The one you liked best when you were a boy.”

The frown disappeared, replaced by a half smile. “‘The Cock and the Jewel,’ I suppose. When a fellow is famished, all the gems in the world will not satisfy his craving for a simple crust of bread, no matter how others might value the pretty jewel.”

Elijah felt a whiff of relief. Little girls could draw roosters and gemstones, particularly with some assistance from their aunt.

“Be off with you,” Kesmore said with a flourish of his whip that had Bacchus looking nervous. “And you”—Kesmore pointed the whip at the horse—“no mischief, or Father Christmas will make you do pony rides all Christmas Day for both girls.”

The horse stood docile as a lamb at the mounting block. Once Elijah was in the saddle, Bacchus turned down the snowy drive without an instant’s hesitation, though Elijah cast one last glance back at the empty third-floor window.

![]()

“What is this?” Louisa, Countess of Kesmore, marched across the nursery and thrust a sketch pad under Jenny’s nose. “It doesn’t look like your work, Sister.”

Louisa did not glide about the house. She did not make small talk. She appropriated neither the airs and graces of a countess nor those of a recently published author whose poetry was acclaimed by the most discerning of the literati. She was simply Louisa: blunt, beautiful, and unfailingly genuine. Jenny loved her for those qualities but was not so enamored of Louisa’s unrelenting curiosity.

“It’s a sketch pad, dearest. The girls leave them all over the house.” With a brother underfoot, they’d learn, as Jenny had, to keep sketches under lock and key.

“I know it’s a sketch pad, Genevieve Windham, but what’s this?” Louisa held out the tablet, flipped open to a pencil drawing of… Jenny, sketching.

Jenny regarded the page with something between dread and fascination. Her hand closed around the sketch pad while her feet clamored to leave the room. “I suppose Mr. Harrison drew it. Some artists must draw compulsively.”

“Like you.” Louisa’s expression held only sympathy. “He’s good, though not as good as you are.”

Louisa was loyal to a fault too.

“Elijah Harrison is the most sought-after portraitist in London, unless you count Sir Thomas Lawrence, who is flooded with commissions and at the regent’s beck and call.”

“Which you ought to be. His sketch of you is quite good.” Louisa came closer to study the drawing. “He’s caught how fiercely you concentrate, like a raptor focusing on her prey.”

“Louisa, I know you are a poetess, but that image is hardly flattering to a lady.”

“Elijah Harrison has also caught you as a woman, Jenny. He drew you full of curves and energy, a female body engaged in a passion, not some drawing-room artifact showing off her modiste’s latest patterns. He sees that your beauty is not merely physical.”

Was that why he’d kissed her, or had it been merely a passing holiday gesture? “You are fanciful, Louisa.”

“I am honest.”

Both could be true, but one didn’t argue logic with Louisa and win unless one was Joseph. “Why do you say I’m better than Mr. Harrison?”

Louisa flipped back to the sketch of Fleur. “Look at this.”

“It’s very accurate, and if he had time to sketch me, as well, he drew both quickly.”

And why had he sketched Jenny, and then told her specifically to examine this sketch pad as he’d trotted out of her life?

“Portraiture is not exclusively about rendering an accurate image,” Louisa said. “Fleur is a happy little soul. She doesn’t have Amanda’s inquisitive nature or impulsivity; she likes to make others happy. Fleur is quick to sense other’s feelings, like my Joseph, but she hasn’t Joseph’s analytical bent.”

Louisa spoke with the assurance of a mother who knew her children. Fleur and Amanda were Louisa’s stepchildren, and Louisa had only known them a year; and yet, by virtue of marital alchemy, Louisa was their mother too.

Jenny did not point out that Louisa’s husband was quick to sense Louisa’s feelings, and probably only Louisa’s feelings.

“What is your point, dearest?” Louisa always had a point, sometimes arcane, sometimes irrelevant to anybody else, but she had a point. Jenny wanted to flip back to the sketch Mr. Harrison had done of her, to study it, to copy it, to see what he had seen when he’d drawn her. Maybe that sketch had a point too.

Louisa moved away, grabbing a receiving blanket from a pile folded near the hearth and shaking it out. “Mr. Harrison didn’t sketch Fleur. He sketched some little girl who looks like Fleur trying to make a drawing. He sketched what he saw, not what he felt.”

Jenny studied the drawing again, and admitted that Louisa’s conclusion was… not invalid. The image was accurate and whimsical, but not… Fleur. Her little-girl eyes, so full of life and vulnerability, didn’t stare up from the page. “He doesn’t know Fleur.”

This was true—it was also a defense of an artist who needed no defending.

“I suspect he doesn’t know children, or he doesn’t know a nature like Fleur’s. She’s purely sweet and easy to love, much like you.”

“Gracious, Lou, you’ve gone from spouting poetry to spinning fiction. I’ll leave you now and give your regards to dear Sophie.”

“And Joseph’s regards to Sindal, too please, and keep the sketches, Jenny. I think Mr. Harrison meant them for you.”

Louisa didn’t smirk as she made that observation. Her green eyes held a touch of pity, though, the same pity Jenny bore lately from her aunt and uncle, her cousins, her siblings, and—she would swear to this—her very own cat.

As she drove the pony cart over the snowy lanes to her sister Sophie’s domicile, Jenny tried not to consider that pity, and yet, it circled her awareness like a shark among shipwreck victims.

The pity rankled because Jenny was pouting over Elijah Harrison passing through her life, leaving her a sketch, and departing without a backward glance.

Pouting was for children, which she would never have. Her family was a group of perceptive, forthright people, and yet, they would not talk about a sister who wanted to pursue art instead of holy matrimony.

They would only pity her.

“For Christmas, I would like to be spared my siblings’ pity.” The pony, a shaggy little scrapper by the name of Grendel, shook his harness bells as if in reply. “I would like to be appreciated for who I am, for my art, and yet…”

As she turned the little gray up the Sidling driveway, Jenny buttoned up her untoward resentments and longings. Paris was a dream, not a just desert.

Sophie, Baroness Sindal, was waiting in the foyer of her sprawling Tudor home, little Kit clinging to her skirts, and the baby—he wasn’t really a baby anymore—perched on her hip.

“Jenny, welcome! Sindal, take the children and let me have a moment with my long-lost sister.”

Sophie’s tall, blond husband hoisted the younger child to his hip and took Kit by the hand. “Jenny, you see how it’s to be. The menfolk banished to the nursery while temptation wafts up from the kitchen. I ask you, how are we to be good little boys when faced with such an ordeal?”

Sindal stood well over six feet, and yet around Sophie he was a very good boy indeed.

“Papa, pick me up!” Young Kit held his arms up and was obliged with a perch on Sindal’s other hip. “’Lo, Aunt Jen Jen!”

Kit shouted everything. Jenny could not recall the last time she’d shouted anything, and silently applauded the boy’s boisterous approach to life.

“Hello, Master Kit. When your mama and I have finished the stollen, will you come down and sample it for us?”

She reached a hand out to tousle his blond curls but stopped short of her goal, fingers outstretched, the child grinning at her. A queerish feeling came over her. Were she not a lady, she would have called it excitement. “Whose scarf is that?”

The scarf in question hung on a hook in the foyer, draped over a gentleman’s greatcoat, the pattern an unusual plaid done mostly in dark purple. When she’d first beheld that scarf, Jenny had noticed the colors—a green stripe, a lavender stripe—because the scheme had been unusual but quite pretty.

“That would be mine.”

Elijah Harrison emerged from the drawing room down the hallway and bowed in Jenny’s direction. “Lady Genevieve, we meet again.”

He was smiling. He was smiling, and he was here, and though she knew her sister, her nephews, and even Sindal were watching her, Jenny was helpless not to smile back.

![]()

Elijah was used to working in spaces not entirely conducive to producing good art, much less great art. He was used to manufacturing sunlight where none existed, opulence of setting where none had ever existed, and personality traits—charm, dignity, sagacity, even chastity—his sitters’ own mothers would never have ascribed to them.

He was not, however, used to ignoring the scent of Christmas baking while he set up his studio. Worse yet, through some quirk of antique architecture, he could hear Lady Jenny’s voice wafting up from the kitchen through the flue, hear her laughter and the lilt and rhythm of her speech, though he couldn’t make out a single word she said.

Fortunately, the Evil Chimney of Distraction had fallen silent about a half hour ago.

Elijah moved furniture around to make window light more available. He organized stretched canvasses, pigments, linseed oil, walnut oil for the lightest colors, brushes, and the containers where he stored bladders of paint, then he moved the furniture around some more.

Where was she? Was she staying under the same roof as he?

“Mr. Harrison?”

At first he thought the chimney had spoken to him, then he realized Lady Jenny stood in the doorway to the guest room he was converting to artistic use.

He bowed. Not because she was a duke’s daughter, not even because she was a lady. He bowed because something in him finally was able to focus now that he knew where she was—and because she was carrying a small tray. “Lady Jenny.”

“I’m having tea sent up, and I brought you some stollen fresh from the kitchen. I gather this is where you are to work?” She hovered in the doorway, much as she had at Kesmore’s house the previous night.

“My temporary studio, the most recent of many. Won’t you come in?”

Won’t you please come in?

He shoved two heavy chairs nearer the hearth, then realized he hadn’t lit the fire. “I apologize for the cold. Moving furniture about warms one up.”

She came closer, peering around as if in a curiosity shop. “You have some of the heat from the kitchens too, I think.”

“Which we will lose if that door remains open.” He crossed the room to shut the door, and not because the room would get cold. “Shall I light a fire for you?”

She set the tray down on the raised hearth and sent him an unfathomable look. What had he said? What had she inferred? Why was she destined to find him in shirtsleeves, cuffs turned back, rumpled, and untidy? He cleaned up decently when he made the effort.

“The tea will be along presently. That will warm us up if needs must. You made a sketch of me.”

She wanted to talk about art, and he wanted to eat whatever was on that tray and simply behold her.

“You made one of me. Artists often perform reciprocal courtesies for one another. For years, my anatomy was available to model for Antoine’s students.” He should not have said that.

“I know.”

And she really should not have said that.

The knock on the door felt every bit as intrusive to Elijah as if they had been on the point of a kiss—another kiss—or perhaps on the point of issuing each other a challenge.

“That will be our tea.” He hustled over to the door, took the tray from the maid in the hallway, and closed the door in the servant’s face. “Shall you pour?”

“While you butter our bread.” She smiled as if this informal, impromptu picnic were a delight to her. Her smile wasn’t loud, and it wasn’t particularly merry.

That smile—he was astonished to conclude—was a trifle naughty.

He dropped into one of the heavy chairs without asking her permission and lifted the linen from the small tray. The scent of yeast and sweet bread hit his nose, and in the chilly room, fragrant steam rose from the half loaf of bread.

“Cutting it when it’s warm is tricky,” she said. “You need a good sharp bread knife and a light touch. Don’t mash it.”

She stirred cream and sugar into his tea while he feathered slices of holiday bread from the loaf. “You don’t skimp on the goodies.” The loaf was liberally full of candied fruit and nuts, to the point that Elijah’s mouth watered.

“My sister Sophie doesn’t skimp on anything related to the comfort or pleasure of her family. This is her recipe, or her version of our grandmother’s recipe.”

“Your grandmamma was German?” The tea in his cup was steaming too. To make a painting of steam was difficult—probably better suited to watercolors than oils.

“We’re German on Her Grace’s mother’s side. My father would call it the dam line, and he’d use that language in company too. About that sketch, Mr. Harrison?”

He passed her a thoroughly buttered slice of warm holiday bread. “First things first. I arrived here after luncheon was served because I detoured clear back to the posting inn to make sure my baggage had been sent on ahead.”

“And like a man, you did not want to impose on the kitchen when you got here, and you forgot to see to your victualing at the inn because you had a task before you. When you arrived here, you denied my sister the pleasure of caring for an honored guest—and you went hungry.”

She was scolding him, which made him want to miss more meals so she might scold him some more. Surely the cold was addling his wits? “You have no patience for the starving-artist mentality?”

She held up her slice of bread, regarding it as melted butter drizzled onto her plate. “Art should be joyful, so joyful it sustains its creator in ways that have nothing to do with physical nourishment.”

He took a bite of bread rather than snort at her naiveté. He’d believed the same thing, once upon a long, silly time ago. “Art should be pretty and remunerative. You say I’m an honored guest, but in reality, I’m a tradesmen reluctantly admitted into houses above my station.”

She took a dainty bite, chewed slowly, and turned an innocent pair of green eyes on him. “You are the heir to a marquess. By rights, you are the Earl of Bernward. You outrank most of your subjects, though I suspect you keep the title quiet because your patrons would be self-conscious in your presence otherwise. Commendable of you, from an artistic standpoint.”

He hadn’t seen that salvo coming, and so he reacted less carefully than he ought. “How do you know I modeled for Antoine?”

Her ladyship munched another bite of holiday bread, not a discernible care in the world. “Your tea is getting cold, Mr. Harrison. I attended those classes whenever I could. Your generosity as a model did much to improve my understanding of the male body.”

He finished his tea in two swallows. “Women were not permitted into those classes. Not ever.” And yet, he’d known she was there practically from the first.

She popped the last bite of her bread into her mouth and dusted her hands together. “I grew tired of drawing kittens and… flowers, much as you might occasionally grow tired of painting corpulent old lords, aging beauties, and strutting lordlings.”

A Renaissance master would have known what to do with her. She was heartrendingly beautiful to the eye, more beautiful the longer he studied her, and yet—she was a minx too. On the order of a saint who prayed with her eyes turned heavenward and much of her cleavage exposed. She likely didn’t appreciate this aspect of her own personality though, which created a conundrum.

“The lordlings are the worst, and I knew you were in Antoine’s classes.”

All the languor in her manner disappeared. While Elijah watched, a blush crept up her neck, turning her perfect complexion quite, quite rosy.

“I suspected you knew when you came to Joseph’s door last night. May I ask how I was found out?”

Relief swept through him, odd but welcome. She’d been bluffing. Those looks, that thoughtful chewing, the “your tea will grow cold,” nonsense had been her attempt at a sophisticated repartee foreign to her nature. He held out another piece of buttered sweet bread to her and wondered why she’d try to misrepresent herself.

“Your sketches were always the best,” he said, helping himself to more tea. “And yet, you never asked many questions, never spoke much at all. You were one of few students who had the sense to move around the room, to change your perspective on the subject from week to week. You took risks. You got down to business as soon as Antoine had described the exercise, and Antoine always had a few words to say to you when he wandered among the students.”

“From that you deduced my identity?”

“Drink your tea before it cools, my lady.”

His words provoked her minx-smile, which hadn’t been their intended effect. He buttered himself more bread rather than smile back. “I followed you home, except you didn’t go directly home. You went in the back door of a modiste’s establishment, and no matter how long I waited, the pale young man with so much dedication and talent never emerged.”

“Though Lady Jenny Windham did.”

“If it’s any consolation, I needed several attempts to figure out your scheme.”

She tore off a bite of bread but didn’t eat it. Even her fingers were beautiful—slender, graceful, elegant. “Why concern yourself at all, Mr. Harrison? You are the darling of the Royal Academy, your talent beyond question. Why would you care about one casual art student?”

A clever reply would have served them both well. They could smile false smiles at each other, finish the tea and crumpets, and perhaps dance a minuet before his nightly nap in the card room if they ended up in the same ballroom next Season.

Half a secret exchanged for half a secret.

He watched the holiday bread crumble to bits in her fingers and chose a different path. “I worried for you.”

She studied her buttery fingers while Elijah tried to find something else to occupy his imagination. “You worried for me, for my safety perhaps?”

Did nobody ever worry for her? Or did she never allow her loved ones to know what she was really about?

“You were safe as houses on the streets of Mayfair in broad daylight, even when you went sauntering down St. James Street in your masculine regalia at midafternoon.” That had been naughty of her—also brave.