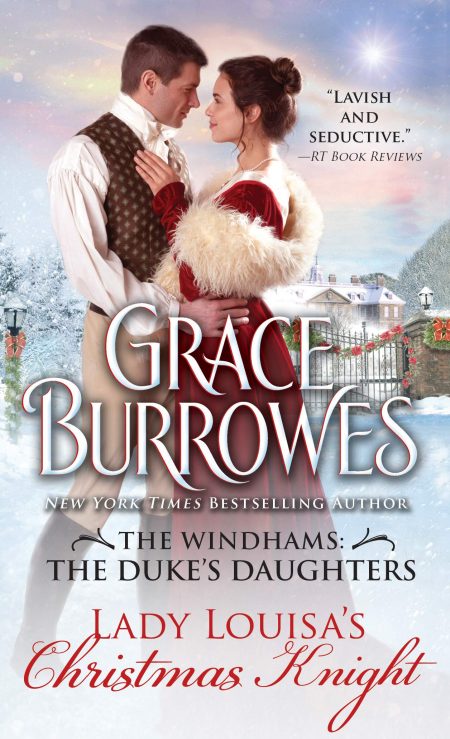

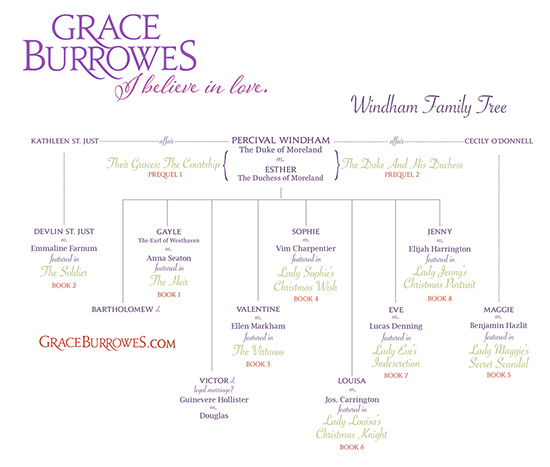

Lady Louisa’s Christmas Knight

Book 6 in the Windham series

Louisa Windham’s fondest wish is to retire from the marital field so her sisters can find decent matches. When Sir Joseph Carrington steps forward to defend Louisa’s honor, she instead find herself married to a man perceptive enough to discern the poet’s heart she keeps hidden beneath her scholarly reserve. Though they are married, Louisa and Joseph still have to learn to trust their love for each other to defeat those who wish them ill, and to ensure their union results in the happily ever after they both deserve.

Bonus Materials →

Enjoy An Excerpt

Chapter One

Sir Joseph Carrington acquired two boon companions after doing his part to rout the Corsican. Carrington was accounted by no one to be a stupid man, and he understood the comfort of the flask—his first source of consolation—to be a dubious variety of friendship.

His second, more sanguine source of comfort, was the Lady Ophelia, whose acquaintance Carrington had made shortly after mustering out. She, of the kind eyes and patient silences, had provided him much wise counsel and companionship, and that she consistently had litters of at least ten piglets both spring and autumn could only endear her to him further.

“I don’t see why you should be the one moping.” Sir Joseph scratched the place behind Lady Opie’s left ear that made her go calm and quiet beneath his hand. “You may remain here in the country, leading poor Roland on the mating dance while I must away to London.”

Where Sir Joseph would be the one led on that same blighted dance. Thank God for the enthusiasm of the local hunt. Riding to hounds preserved a man from at least a few weeks of the collective lunacy that was Polite Society as the Yuletide holidays approached.

“I’ll be back by Christmas, and perhaps this year Father Christmas will leave me a wife to take my own little dears in hand.”

He took a nip of his flask—a small nip. Unless he spent hours in the saddle, or hours tramping the woods with his fowling piece, or a snowstorm was approaching, or a cold snap, his leg did not pain him too awfully much—usually.

“I honestly do not know how you manage it, my dear. Ten piglets, twice a year, for at least as long as I’ve had the pleasure of your acquaintance.”

She apparently hadn’t caught yet this season, though, and winter had arrived. This was worrisome on a level a man not yet drunk didn’t examine too closely. Ophelia’s fecundity provided reassurance of a fundamental rightness about life—reassurance far more substantial than that held by Sir Joseph’s flask.

“Get me some piglets, your ladyship.” He switched ears, and his friend tilted her heavy head into his hand. “Get me the kind of babies I can sell at market and grow rich on. Richer. For Christmas, a litter of twelve would do nicely.”

Her record was eleven, and every one of them had lived. That had been two years past, when Sir Joseph had been desperately in need of some kind of positive omen.

A groom whistling the aria “He Shall Feed His Flock” in the manner of a holiday jig let Sir Joseph know that his mount was ready. The lad would not intrude on a private audience between Sir Joseph and Lady Ophelia, not when the groom could abuse poor Handel without mercy instead.

“I’m off. Say a prayer for Reynard.”

With a final pat and a scratch, Sir Joseph left his porcine friend to join his neighbors.

Hunt meets reminded Sir Joseph of the army on parade: All the finery was visually impressive and the great good cheer and bonhomie on both occasions fueled in part by nerves and liquor. The agenda of the day in both cases was ostensibly virtuous, and yet, if all went according to plan, somebody not of the assemblage would die a bloody death.

That the somebody was a fox—mere vermin—and outnumbered by the hounds often thirty-couple to one never seemed to bother anyone but Sir Joseph. Even amid the great good cheer of a December hunt meet, he knew better than to share his sympathies for the animal with another human soul.

![]()

“The Little Season is a great pain in my backside.”

Lady Genevieve Windham hadn’t bothered to speak quietly, which her sister Louisa found surprising. True, grumbling to one’s sister ought always to be a safe thing to do—Louisa had no use for the Little Season either—but riding in at the back of the third flight, they could come within earshot of their neighbors.

“We’ve missed all but the last two weeks of it,” Louisa pointed out. “Thank God for Papa and his hunt madness.”

“It’s like hunting grouse,” Jenny said, letting her mare drop back farther from the other riders ambling toward the hunt breakfast. “Lent ends, and the husband hunting begins, the mamas beating their charges forward into the waiting guns. I don’t know how many more years of this I can take, Louisa.”

“One grows used to much of it.” This was not quite a lie, though Jenny’s rare moment of low spirits required the kindess of… prevarication, at least.

“You’ve been at it a little longer than Evie or I, and I should not be complaining to you. I do apologize, Lou.”

Jenny’s tone was genuinely contrite for she was truly good, truly considerate, things Louisa had long since stopped aspiring to. Jenny had angelic blond good looks to go with her generally cheerful disposition, in contrast to Louisa’s dark hair. In a despairing moment, Her-Grace-their-mama had called Louisa’s features bold.

Alas, that was no lie at all.

In the meadow below, other riders were straggling in from the morning’s hunt. A group of bobbing feathers caught Louisa’s eye: Two pheasants, a peacock, and an ostrich plume dyed—may the sainted bird never learn of it—pink.

And clearly, those hounds were following a scent. Louisa scanned the meadow, her pleasure in the morning’s hunt evaporating when she saw their intended prey.

“Jenny, I feel a charitable impulse about to overtake me.” For of all men, Sir Joseph Carrington did not deserve to have the pack descend upon him.

Jenny stopped fiddling with the single tuft of mane unbraided over her mare’s withers. “You haven’t yielded to an impulse in at least five years, Louisa. Logic is your sole guiding… oh, dear.”

“The hounds are running riot,” Louisa muttered. “The poor man can’t even see them coming.”

A single rider mounted on a black gelding walked his horse across the meadow on a loose rein, while above and behind him, the four ladies trotted their mounts in pursuit.

Louisa had been stifling impulses successfully for eight years, did Jenny but know it. She wasn’t going to stifle this one. “Blame my recklessness on the approaching season. Sir Joseph doesn’t stand a chance against all four of them at once.”

The prospect of a decorated veteran, a knight of the realm no less—also a widower and a papa—being swarmed by Isobel and her band of marriage-mad minions wasn’t to be borne.

Louisa nudged her mare into a canter, cutting over a stream, two logs and a stile, with Jenny bringing up the rear. Sir Joseph Carrington had served with her brothers Bart and Devlin on the Peninsula which further assured his place in that class of men whom Louisa respected without question.

He also had no sisters, cousins, or aunties who would rescue him from the fate trotting up behind him. None of the fellows riding in would dare lend assistance either, of course, lest they be drawn into the affray and find themselves dancing with every unmarried lady in the shire at the evening’s ball.

Louisa knew what it was to contend with one’s fate in isolation, knew the loneliness and exhaustion of it. She suspected Sir Joseph might too, and if she could spare him this small ambush, she would.

“Sir Joseph,” Louisa called as her mare cut in front of the other four riders by two dozen yards. “Good morning! Excellent final run, wasn’t it?”

Sir Joseph glanced back toward Louisa, which allowed her to see the moment when he realized his peril. “Lady Louisa, Lady Genevieve. Good morning.”

He didn’t quail at the pack closing in on him. He tipped his hat in casual greeting then faced forward again. Devlin had said Sir Joseph was a demon on dispatch—brave and unflinching. His battle instincts were apparently still in working order.

From the corner of Louisa’s eye, she saw Isobel Horton of the pink plume glowering a sentiment not at all in keeping with the approaching Yule season.

Happy Christmas to you, too, Isobel. “Jenny, weren’t you looking for some help with setting up the hunt breakfast?”

Jenny’s smile as she came up on Sir Joseph’s off side could have graced a saint. “So, I was. Sir Joseph, if you’ll excuse me?” She turned her mare. “Oh, Ladies! Isobel, Elspeth, I am ever so glad to see you. And Isobel that is the most cunning hat….”

Sir Joseph watched this maneuver, a hint of a smile hovering on his dark features. “Neatly done, Lady Louisa, and please thank Lady Genevieve when next you see her.”

Louisa inclined her head, lest he catch her smiling.

Carrington’s voice did not lie easily in the ear. His bass-baritone growl lacked the plummy vowels and aristocratic musicality of either public school or university. Louisa liked this about him, liked that he wasn’t all pretty manners and mincing vocabulary. She liked even more that he knew exactly what had just transpired and didn’t pretend otherwise.

“Care for a nip?” Sir Joseph held out a silver flask engraved with an unfurled rose bud. The thing looked incongruously small and elegant in his black-gloved hand. “And in case you’re wondering, there’s a combination of rum and hazelnut liqueur in here. It warms the bones.”

She accepted his flask, appreciating the gesture, though he likely would have made the same offer to Isobel or Jenny. In the hunt field, there were frequent stops to “check one’s tack” or let the horses blow while the hounds were cast. When the weather was brisk, these pauses invariably involved a tot of whatever was in one’s flask. Even the ladies were permitted a discreet nip—Louisa had drained her flask before the second run.

“That is… good.” Bracing, even. The brew itself was warmed by Sir Joseph’s body heat, giving the spirits a mellow fire when imbibed. Louisa took a second sip and passed the flask back.

A very agreeable combination, indeed.

Sir Joseph helped himself to a swallow, and the flask disappeared into an inner pocket of his hunt coat. “I admit to some puzzlement, my lady: You are a bruising rider, well able to keep up with the hounds, even to leading the first flight, and yet you lurk at the back with the inebriates and the timid. You have piqued my curiosity.”

Piquing a man’s curiosity was not a good thing in Louisa’s experience, though the part about being a bruising rider was lovely coming from a former cavalry officer.

“I keep my sister company.”

“Ah.”

Men had the ability to mock with a single syllable. Certain men. Louisa’s five brothers had been born with this ability, and yet, she didn’t think Sir Joseph meant to make fun of her.

“Lady Genevieve rides quite well,” Louisa admitted. A good lie was based as much as possible on truth. Her brothers had taught her that too. “She is softhearted though, and does not like to risk being in at the kill.”

“I see.” The smile was back, very subtly. Louisa wanted to stare at the man to see if that smile ever broke forth into the genuine article.

Staring would not do, however. Louisa gained a moment’s pause to think up another conversational gambit when Sir Joseph’s horse began to passage. The animal was far from dainty, and yet, when it collected itself like that, quarters lowering, trot steps becoming elevated and cadenced, man and beast each looked elegant and elementally… attractive.

“Enough of this nonsense. Settle, you.”

When Carrington spoke to his horse, his voice was different—purring and affectionate, not growling. The horse relaxed back into a walk while the rider stroked a hand over its mane.

“He is quite an athlete, Sir Joseph, and yet I noticed you also avoid the first flight.”

“Sonnet is anxious for home now. He and I are alike in that regard—most comfortable among familiar surroundings. To reply to your observation, Lady Louisa, all I can say is that war has changed the way I view blood sport, to the point where I find the term an oxymoron. Will you be going up to Town before Christmas?”

Louisa knew what oxymoron meant, along with onomatopoeia, synecdoche, and anthropomorphism—for starters. Perfect gentleman was an oxymoron. Perfect lady was too.

“For the next two weeks, my sisters and I will remove to Mayfair with Their Graces.”

“Do I surmise that this is not a cause for rejoicing?”

Louisa turned her head to regard him and found his gaze was serious—too serious? “Are you teasing me, Sir Joseph?” Her brothers—brave men each—used to tease her, before her schoolgirl arrogance had taken one of their dares to a disastrous conclusion. She did not miss their nonsense whatsoever.

Sir Joseph leaned a little closer in his saddle and glanced around, as if imparting a great confidence. “I am commiserating, I think.”

He straightened, swiveled his eyes front, and kept speaking. “I go up to Town in spring and autumn and each time wonder if I’m not becoming more like my great-uncle Sixtus. For the last forty years of his life, he never once set foot in London, and each decade, he professed to be happier than the one previous.”

“This would be the fellow from whom you inherited your property?”

“My farm.”

His farm was thousands of acres. According to His Grace, they were very good acres, and Sir Joseph took excellent care of them. Lucky man, to be able to rusticate where one could see stars at night and go for a pounding gallop come morning.

Ahead of them now, Jenny and her companions were chattering back and forth, no doubt weaving a conversation about watercress sandwiches or something equally riveting.

“London isn’t so bad,” Louisa said. London was tedious, crowded, and full of people with a bewildering ability to talk much, say little, and apparently enjoy themselves in the process. “Christmas will see us back out to Morelands in a very short while.”

“Two weeks can be an eternity.”

He said this with something like resignation. Louisa saw him put his reins in one hand and fish inside his hunt coat for his flask, though he neither withdrew it nor imbibed any more of his personal brew—more’s the pity. She could have used another tot. Two weeks was, after all, one million two hundred nine thousand six hundred seconds.

Perhaps he could have used a tot too. His expression was bleak, but then, Sir Joseph’s expression was usually bleak. He was not a classically handsome man—his features were saturnine, his brows a trifle heavy, his nose not quite straight, though bold and a bit hooked. He yet managed to be attractive to Louisa for she had seen him smile.

Just the once, he’d smiled at his small daughters one day in the church yard, but Louisa had never forgotten the sight. His smile, full of warmth, humor and affection, made him very attractive indeed.

“Will you be attending the hunt ball, Sir Joseph?”

“One does.”

Yes, one did. Louisa suspected this was more of his unflinching bravery at work. “Shall I save you a dance?”

She regretted the impulse as soon as the words were out of her mouth, though not for herself. Dancing was one social activity she enjoyed, provided her partner was halfway competent. She regretted her question for him. Sir Joseph limped, and Louisa wasn’t sure the fellow was even capable of dancing.

He petted his horse again, a soft stroke of black leather down a sleek, muscular crest. “I can manage the promenade. A sarabande or old-fashioned polonaise is usually within my abilities early in the evening. I haven’t attempted waltzing in public in recent years and hope to die in that state of grace.”

“The promenade, then.”

As they approached the hunt breakfast, Louisa tried not to think of Sir Joseph growing old without ever again knowing the pleasure of sweeping a lady around the ballroom to the lilting strains of a waltz. If Louisa dwelled on such thoughts, she’d be at risk for pitying Sir Joseph. A man possessed of unflinching bravery, an excellent seat, and a half full flask would have had no use for her pity whatsoever.

Louisa Windham had preserved Joseph from enduring the company of Miss Fairchild and her giggling familiar, Miss Horton for the duration of the hunt breakfast, and possibly at the hunt ball as well. They’d been looking for him all morning, like a couple of hounds on the scent of the fox. Eyes bright, yipping inane compliments to each other, their gazes searching the first flight for their prey, then the second…

While Joseph had the company of a pretty woman with no designs on his person, his purse, or his pork.

He assisted Lady Louisa from her horse, which allowed him the realization that she was not as substantial as her height might have suggested. When she slid to the ground, he collected one other little fact about her: Despite the morning’s activity, the scent of citrus and cloves clung to her.

Expensive, and in the brisk air of a bright winter morning… Christmasy. He liked it.

He liked her, in fact, though he would never burden the lady with such a confession. In the two years since he’d been turned loose on the local Kentish gentry, he’d spent considerable time on the edges of drawing rooms and dancing parlors, visiting in the churchyard, and tending to the neighborly civilities.

From what he’d observed, Lady Louisa went her own way, as much as such a thing was possible for a duke’s unmarried daughter. She spoke her mind and had a saucy mouth.

Also a saucy bottom. He particularly liked her saucy bottom. He enjoyed the way her riding habit revealed a bit more flare at the hips than was fashionable, and the way she made no effort to hide the Creator’s generosity with her fundament.

She was a woman a man could get his hands on…

“Sir Joseph?”

He stepped back from her while grooms led their horses away. “May I fetch you a plate, Lady Louisa? Something to drink?”

How long had he been standing there, contemplating her backside in the midst of their neighbors, the hounds, milling horses, and bustling servants?

“I could use some sustenance.”

That she did not demur and swan off in search of her sister surprised him and pleased him. “As could I. Shall we?” He winged his arm at her, more willing to remain at her side than a gentleman would admit.

Though if he again thanked Louisa Windham for using her superior social standing to rescue him from certain capture, she’d likely give him a puzzled look, change the subject, and forget she’d promised him the opening dance.

Which he was looking forward to, oddly enough.

From several places ahead of them in the buffet line, Timothy Grattingly and some other young fellow started arguing about the ideal breeding for a morning horse.

“They would not appreciate Sonnet,” Joseph murmured as the lady added apple slices to the plates he held. “He’s good English draft on the sire’s side, and pure Spanish on the dam. A woods colt who saved my life more than once.”

Louisa Windham aimed an impatient glance at the young men and their escalating disagreement. “Sonnet has a good set of quarters on him, good bone, and he’s sane. I don’t see that much else matters. Where shall we sit?”

Where the hounds would not find him, where he could enjoy more of Louisa Windham’s tart common sense and sweet fragrance. “A little quiet wouldn’t go amiss, in the sun and out of the breeze.” The weather being nippy, even in the sheltered environs of their host’s stables.

She shot him a tolerant smile, suggesting the lady had divined his strategy. “There,” she said. “That bench.”

Louisa had chosen a wooden bench flanking a dry fountain and a bed of dead asters. While Joseph remained standing with their plates, Louisa set their drinks on either end of the bench, unpinned her hat, rearranged her skirts, and otherwise caused the kind of fuss and delay natural to women.

He ought to have resented it, as hungry as he was, as much as his leg was starting to throb. Instead, he noticed that when Louisa pulled loose her hat, a lock of her dark hair abandoned its intended location to coil along the column of her neck.

She did not seem to notice or care, while he could not stop noticing.

Perhaps a trip to Town—to the fleshpots of Egypt, as it were—was not entirely a bad idea. A gentleman farmer who’d behaved himself the livelong year could do with some recreation at Christmas, after all.

“I’ll take those.” She reached up and plucked both plates from Joseph’s grasp, gesturing with her chin for him to sit.

His preoccupation with the flawless, pale, and possibly clove-scented skin of her neck, or the exact feel of that fat, dark curl of hair against his fingers vanished as he realized he was going to have to get his arse on the bench beside her. A graceless moment awaited him. After he’d ridden for several hours, the joints of his right leg were not strictly reliable in their functioning.

He managed. It was a matter of moving stiffly, stiffly, then for the last few inches, nigh collapsing onto the bench, like an old man too stubborn to make proper use of his canes.

“Does riding bother your injury?” Lady Louisa started munching on a slice of apple after delivering her inquiry.

“There’s a balance. If I ask too much, it worsens; if I ask too little, it worsens.”

“And nobody asks you about it, do they? Care for a bite of apple?”

He enjoyed apples. He wasn’t sure he enjoyed talking about his injury—now that somebody had inquired.

“War wounds are old news.” He accepted a slice of apple from her hand. They’d removed their gloves to eat, of course, which meant he noticed the contrast: His hands were callused and bore a scar, a white slash that made a hairless track across the backs of all four fingers of his right hand. Her hands might have belonged to a Renaissance tapestry virgin stroking some fool unicorn’s neck.

She frowned at his hand as a three-legged hound went loping past, sleigh bells jingling merrily on its collar. “Another injury?”

“An attempt by a French soldier to relieve me of the reins. He was not successful.”

Thank God. Joseph slammed a mental door on the memory—something he’d become adept at—and accepted another bite of apple from the lady beside him. “Are you ever bored, Lady Louisa?”

She paused in a rather purposeful effort to clean her plate, glancing up at him with a puzzled frown. “What brought that on?”

No tittering reply, no simpering or casting lures, and the lady had both a kind heart and a lovely appearance. Better still, Joseph would open the evenings’s dancing with her for a partner.

Joseph waved his scarred hand. “Talk of injuries puts me in mind of boredom, perhaps. The recovery was a greater challenge than the initial harm. One does wonder what a duke’s daughters find to amuse them.”

“I have wondered the same thing. We make calls, we have charitable endeavors, we correspond with our sisters, sisters-by-marriage, and cousins. We attend social functions, and when in Town, ride or drive in the park. It’s all quite…”

She fell silent, leaving Joseph with the sense he’d just glimpsed a hurt that wasn’t healing all that well. He patted her knuckles. “I read.”

Another look, much more guarded. “One assumed you were literate.”

He read to his pigs, more often than not. “I read more than just the journals and classics, Lady Louisa. I am left to my own company a great deal, and winter nights are long and cold.”

She perused the contents of her plate, which spared him any more inquisitions from dark green eyes. “They are. Jenny spends them sewing or painting—she must create. Sophie was our chief baker until she married Sindal, Eve is Mama’s boon companion for the social calls, and Maggie frolics with her account books when she’s not making calf eyes at Hazelton.”

“I correspond with your-sister-the-countess regarding business matters.” He also noted that Louisa’s little recitation included no activity of choice for herself.

“With Maggie?” Another pause in her eating. “She would be so bold as to correspond with a single gentleman and no one the wiser. Droit du spinster, she’d call it. I used to think Mags had a pound sign where her heart was supposed to be. Little I knew.”

She tore off a bite of Christmas stollen with particular focus, suggesting there was Family Business lurking at the edges of the conversation. Joseph took a sip of his punch then set the glass aside.

“Drink with caution, my lady. There’s some turned cider somewhere in the recipe.”

She studied her bite of holiday bread. “It’s always like this, isn’t it? At the hunt meets we bundle up in our finest, slap on our company smiles, fill our plates, and yet, there’s always something… sour punch, a horse that has to be put down, a neighbor retching in the bushes while his half-grown son tries not to look hopeless.” She put her mostly empty plate aside. “I’m sorry. I should perhaps find my sister.”

Joseph had never considered himself more than passingly bright, but his powers of observation had been sharpened by the inactivity occasioned by his injury. Pretty, kind, titled and well dowered Lady Louisa was dreading her next trip to Town, maybe all her trips to Town. She had no hobbies or pastimes she’d mention in public, and both of her older sisters were married.

And yet, she’d ridden to the rescue of a man she barely knew, perhaps because she heard the hounds in full cry all too often herself.

Joseph got out his flask. “Life can be like that, tarnished around the edges.”

Mostly to divert her, he reached over and tucked the errant curl behind her ear, finding her hair every bit as silky and pleasing to the touch as he’d imagined. He could write a sonnet to that single lock of hair.

Perhaps he would.

“It’s true as well, my lady, that we’re both in good health, we have friends and neighbors who will miss us when we’re gone, we have food to eat and warm beds to sleep in, and Christmas will soon be here.” He did not mention that they’d be sharing the promenade.

She hadn’t flinched at his touch. She studied him from serious green eyes. “You learned this while at war too, didn’t you? You learned to be grateful.”

“Perhaps I did.” He’d learned something—how to content himself with agriculture, solitude, and good literature, perhaps. Almost.

“His Grace says you are also leaving for Town tomorrow, Sir Joseph, though one wonders why.”

Her query was too insightful and made him abruptly reassess her with her serious pretty green eyes, lovely scent and silky hair. “The same reason we all go up to Town. I must socialize occasionally if I’m ever to find a spouse. Would you care for another nip?”

“Yes.” She accepted his flask and held it to her lips. While Joseph again admired the graceful turn of her neck, she tilted the flask up, as if she were intent on draining it of every last drop.

![]()

“Why would Sir Joseph Carrington be in need of a wife?” While she spoke, Louisa accepted a mug of mulled wine from one of the footmen circulating around the ballroom. There were little bits of cinnamon floating on top, a display of holiday extravagance on the part of the family hosting the hunt ball. Mistletoe hung in the door arches, and wreathes festooned the doors. The fragrances of evergreen and beeswax lurked under the scent of too many bodies that hadn’t bathed since the morning’s ride.

Eve waved the footman away without taking any wine for herself, though Jenny was too polite to decline.

“Maybe Sir Joseph seeks a wife because he has children,” Jenny volunteered. “Little girls need a mother.”

“Maybe because he’s lonely,” Eve suggested. “He’s a comely man. He can’t be much more than thirty, and Maggie says raising swine is quite profitable. He doesn’t seem inclined to the usual male vices, so why not have a wife?”

Louisa sipped her wine, recalling Sir Joseph at Sunday services with the two little minxes who called him Papa. “You think he’s comely?”

Eve Windham, the youngest of the ducal siblings, rarely ventured an opinion about any member of the male gender. She collected hopefuls and followers and even proposals with blithe good cheer, but never gave a hint her heart was engaged by any of them.

Eve’s gaze traveled across the ballroom, to where Sir Joseph was in conversation with the plump, pale Lady Horton. The woman’s two eldest daughters flanked him—penned him in like a pair of curious heifers would corner a new bull calf.

“I like a man who isn’t silly,” Eve said. “I like a man who will be able to provide for me and mine; I like that he’s a papa—though he’ll want sons to pass along all that wealth to—and a pair of broad shoulders on a fellow doesn’t exactly offend, either.”

Jenny’s blond brows rose. “From you, Eve, that’s a ringing endorsement. Were he not a mere knight, I’d be passing your notice along to Mama.”

“It doesn’t matter that he’s a mere knight,” Eve said, though her rebuke was mild. “Is the libation any good?”

Louisa wrinkled her nose. “Too sweet. Some people must use the holidays to inform all and sundry of their wealth.”

“You’re cross tonight,” Jenny said. “I know something to cheer you up.”

Eve’s lips quirked, and the look that passed between Louisa’s sisters was conspiratorial and mischievous. Eve and Jenny shared more than blond beauty, though Jenny was willowy and Eve was a smaller, curvier package. Louisa’s remaining unmarried sisters both had a sort of gentleness to them, a warmth of spirit toward all in their ambit that Louisa lacked.

And envied, truth be known.

“I can use cheering up,” Louisa said, picking up the thread of the conversion. “My evening starts out promenading with Sir Joseph, and my dance card is empty thereafter. Sindal will no doubt take pity on me, but he fairly heaves one off the dance floor in an effort to return to dear Sophie’s side.”

“Deene would dance with us were he not in mourning,” Eve observed.

“But he is in mourning.” Which was a shame. The Marquis of Deene was tall enough, a fine-looking fellow, and more family friend than anything else, which meant for Louisa’s purposes he was safe.

“Lord Lionel Honiton is not in mourning,” Jenny said, “and he’s just now coming down the steps.”

Hence the knowing sororal glances. Louisa did not look up as she set aside her glass of too-sweet, lukewarm wine punch. “He declined to ride today. I wasn’t sure he was coming.”

Nor had she missed him, though that hardly need be said.

“Too busy choosing his attire for the evening,” Eve replied. “I swear he outshines the ladies.”

Lord Lionel was all golden good looks, with brown eyes that put Louisa in mind of Her Grace’s spaniel. When Louisa glanced over Eve’s shoulder to take in his lordship’s progress down the stairs, she saw he had as usual troubled over his turnout.

A handsome man who knew how to wear lace was a beautiful creature, regardless of his other attributes. Lionel sported just a touch here and there—his throat, his cuffs—but it was golden-blond lace, which complemented his fair coloring and his blue-and-gold ensemble marvelously. His cravat pin would be something perfect—sapphire or topaz set in gold, perhaps—and the sleeve buttons at his cuffs would match it.

“Louisa’s saving her supper waltz for Lord Lace,” Eve murmured. “I declare that man wears more gold for a hunt ball than I have in my entire jewelry case.”

“He maintains standards,” Louisa said. Town standards, even Carlton House standards–assuming the jewelry was real, which Louisa doubted. “And he dances well enough.”

Louisa knew of what she spoke, for she’d had the pleasure more than once. When one danced with Lord Lionel, there was a sense of the entire room pausing to watch. That he seemed to know it was only to be expected.

She considered that he chose her as a dance partner because she was, first and foremost, of suitable rank—a duke’s daughter could dance with a marquis’s son—and because her dark coloring set off his golden male beauty. Then too, she was a good dancer.

“He’s coming this way,” Jenny said, peering into her still-full glass. “I’d say he’s about to speak for your supper waltz, Lou, and before he’s done much more than greet the hostess.”

“Good evening, my ladies.”

Louisa stifled a groan of relief at the growled salutation. “Sir Joseph, good evening.” Her sisters offered their curtsies, and Jenny—bless her—launched into the civilities.

“Marvelously mild weather today for the holiday hunt, wasn’t it?”

Sir Joseph, severely resplendent in dark formal attire, appeared to consider Jenny. “One wonders if Reynard shares that opinion. He probably starts praying for nasty winter weather no later than April of each year.”

“In spring,” Louisa said, “he and his vixen are likely concerned with family matters.”

Sir Joseph’s lips twitched while Eve and Jenny both managed to look pained. Family matters— what had she implied? Louisa stared at the cinnamon bits floating on her awful drink.

“Perhaps he is,” Sir Joseph said. “Perhaps he thinks of going up to Town early so he might confer with his tailors before the Season advances. Rather than discuss the sartorial habits of the fox, Lady Louisa, might I remind you that you’ve promised me your promenade? The orchestra is tuning up, though I shall certainly understand if today’s exertions left you too fatigued to allow me the privilege.”

He was giving her a way to decline their dance. Behind Jenny, Lord Lionel had paused in his progress across the room to speak with Isobel Horton. The girl had refined the simper to an art and was clinging to his arm like a barnacle. He gave Isobel his undivided attention, those brown eyes of his turned on the woman as if she were the light of his existence.

What would it take to inspire Sir Joseph to look at a woman like that?

“Louisa rarely passes by an opportunity to stand up,” Jenny said. There was an urgent note in her voice, as if Louisa had missed a conversational cue.

“Jenny’s right.” Louisa shifted her gaze from Lord Lionel’s peacock splendor to Sir Joseph’s sober face. “The more I’m on my feet, the less I’m left trying to make small talk, which as you’ve no doubt surmised, is not one of my gifts.”

“Nor mine.” He winged his elbow at her. That’s all. As overtures went, it had a certain compelling simplicity.

While Lord Lionel scribbled on Isobel Horton’s dance card, Louisa took Sir Joseph’s arm. She assumed her place at his side among the other couples preparing to stroll their way through the opening of the evening, and was assailed by a troubling thought: Was Sir Joseph partnering her because he thought she was in need of rescuing? Was this charity on his part?

The possibility was not as lowering as it should have been. Louisa instead found it… intriguing.

She could not marry, not while the threat of scandal hung over her like a blighted sprig of mistletoe, but she ought to be allowed to stroll the perimeter of a ballroom on the arm of a handsome man, shouldn’t she?

Chapter Two

“I can recite poetry to you,” Sir Joseph said when Louisa had walked with him halfway down one side of the room. “Poetry would preserve us from silence and yet require no thought on anybody’s part.”

Poetry? Louisa’s heart tripped. “Are you teasing me?”

“Oh, perhaps. You could nod occasionally or beat me on the arm with your fan, and no one would know we’re ducking the obligation to converse. I have a friend who’s partial to the Shakespeare sonnets.” He paused while Louisa cast around for something—anything—to say, but he spared her by launching into a quiet, almost contemplative recitation: “‘That time of year thou mayst in me behold, when yellow leaves, or none, or few do hang on boughs which shake against the cold…’”

Across the room, Isobel Horton smacked Lord Lionel’s arm with her closed fan.

Louisa adored that sonnet, which Sir Joseph had begun with just the right balance of regret and warmth. “Why don’t you instead tell me why you’re hunting a spouse, Sir Joseph?”

He grimaced. Her question was graceless, but there was no calling it back. “Hunting? Striding about in my gaiters, my blunderbuss primed and ready to take down some unsuspecting little dove in midflight? I suppose the image is not inaccurate. I require a wife for two reasons.”

He required a wife. Women longed for a husband, they dreamed of children to love. They were not permitted to require a husband. Brave he might be, and possessed of marvelous taste in poems, but Louisa wanted to smack Sir Joseph, and not with her fan.

“Two reasons. Please explicate.”

They were forced to a halt by the couple before them, who appeared too busy flirting to manage even forward steps in time to the music.

“First, I am responsible for two girl children, and the influence of an adult female in the maternal role is desirable on their behalves.”

In the part of her brain that reveled in language, that regarded every spoken sentence as aural architecture, Louisa noticed that Sir Joseph managed to allude to being a parent without acknowledging any relationship. He did not say, “My daughters need a mother,” nor did he say, “I am in want of a wife to mother my children.”

He fashioned a job description, though an accurate one under the circumstances.

“The second reason?”

He glanced around. He waited until the lovebirds ahead were moving along, proceeding as a three-legged unit, heads bent so close as to ensure talk. Louisa wanted to smack them, as well, perhaps with the butt end of Sir Joseph’s blunderbuss.

“There is a title.”

She forgot the lovebirds and nearly forgot Lord Lionel halfway across the room, suffering the press of Miss Horton’s udder against his arm.

“I beg your pardon?”

“There is a title.” He sounded weary as he spoke, his voice barely above a whisper. “The barony has been in abeyance for more than two hundred years, and God willing, it will remain in abeyance.”

Abeyance. Abeyance could keep a title dangling just out of reach on a family tree for centuries. Abeyance befell the old baronies, when the holder of the title left only female descendents, who increased and multiplied and were fruitful, making it impossible to choose to whom the title ought to descend, because various heirs had equal claim on it.

“You do not sound pleased about this.” He sounded horrified, in fact.

“I am in fervent hopes a fourth cousin, Sixtus’s descendent of the same name, the only other contender, will shortly be in expectation of a happy event with his young wife. Each year, I await his Christmas correspondence, hoping a new little cousin of the male persuasion will have arrived in the preceding year.”

“You don’t want a title?”

They stopped perilously close to a dangling spray of mistletoe, and he… shuddered. The broad-shouldered, plainspoken man who’d been knighted for bravery shuddered. “Consider, Lady Louisa, that our regent is nigh profligate handing out titles. What if he took a notion to elevate the title above a barony? What if he recalled that my knighthood was earned in combat? What if his great capacity for sentiment should affect his generous heart, and… a knighthood is bad enough. A barony would be nigh intolerable, and anything worse than that enough to send a sane man to Bedlam.”

Perhaps Sir Joseph’s courage was not limitless. Louisa’s certainly wasn’t. “You would be Lord Somebody, Sir Joseph. You’d sit in the Lords, you’d have your pick of the debutantes.”

She managed to stop herself from pointing out that even his hog farming would be overlooked. Farming was not trade; it was solidly agricultural. Bacon, ham, lard, and leather being necessities, every title in the land probably raised some swine.

Louisa also did not ask the man what he thought of dukes—or duke’s daughters—if baronies were nigh intolerable. “You must marry in part because of this title.”

Sir Joseph huffed out a sigh then moved them away from the Mistletoe of Damocles. “I did not say I must marry. I am not averse to the notion because of the girls, and then there is this remote, distant, though not quite theoretical business of a title. Titles come with responsibilities, and my cousin is not young.”

A duke’s daughter grasped his point: He’d need an heir. A title should not languish for two hundred years in abeyance, only to fall into the Crown’s greedy clutches through escheat immediately thereafter.

“Perhaps this year, your cousin’s union will be fruitful.”

“One offers prayers to that effect, though this is his third union.”

The couple before them was whispering, heads bent so close the young man might have stolen a kiss with less impropriety.

“Sir Joseph, I find I’m thirsty. Would you be offended if we abandoned the promenade and sought some refreshment?”

He said nothing. He fairly yanked her out of the line of other couples and headed for the table where more poor quality, not-quite-warm, gaggingly sweet wine awaited them both. She went along with him and pretended to sip her drink, though the evening stretched before her as an interminable exercise in appeasing seasonal social obligations and evading strategically hung boughs of mistletoe.

Meanwhile, across the room, Miss Horton pressed, Lord Lionel laughed, and the orchestra played on.

![]()

“The secret to a short and successful courtship is to pick a desperate woman.”

Lord Lionel Honiton’s cronies laughed predictably at this sally from one among their number. Lionel took a sip of good brandy—Petersham was hosting, and he was still too new to Town to understand that those who drank his brandy and fondled his housemaids were not necessarily his friends.

“You miss the mark,” Lionel drawled to the wit lounging in a cushioned chair near the hearth. “A desperate girl is the secret to a short courtship ending in marriage, I’ll grant you, but better still if her parents are desperate, in which case the settlements will see the thing done successfully.”

A round of right-hos, hear-hears, and what-whats followed, along with another circulation of the brandy decanter.

“And then”—the wit held up his glass as if to toast—“there’s the wedding night.”

More hooting and stomping, because the hour was growing late, and the decanter was seeing a great deal of action. These same fellows would cheerfully call one another out over a slur to a woman’s honor before dinner. Four hours later, they were degenerating into the overgrown schoolboys they were, ready to hump anything in skirts and to cheer one another on in the same cause.

While the assemblage began to debate just how many Seasons it took to create desperation in a decent young woman, much less in her parents, Lord Lionel topped up his glass.

“You’ll regret that in the morning,” said a voice to his right.

Lionel held the glass in both palms, letting the heat of his hands warm the liquid. “I will do no such thing. You are far too sober, Harrison, if you think I’ll even be abroad during anything approaching morning.”

Harrison was visually appealing, lounging against the mantel, a lean, dark contrast to Lionel’s own Nordic coloring. He was also serious to a fault, which allowed Lionel to appear the wit by contrast. All in all, a useful association—for Lionel.

“You’ll be abroad in daylight.” Harrison’s tone was mocking, condescending even.

“Perhaps I’ll be making my way home in the morning, as the term technically applies past the witching hour, but as for the broad light of day”—Lionel paused for another sip—“heaven spare me.”

“You’ll be about because Lady Carstairs’s Christmas breakfast is tomorrow, and very likely, all three Windham sisters will be on hand. You’ve been currying the favor of that trio all year.”

“Have I?” Lionel yawned, scratched in the general area of his… upper thighs, and peered at his drink. “Three of them, you say?”

Harrison’s dark eyes narrowed.

Elijah Harrison was a hanger-on. He painted portraits, which meant he wasn’t even a gentleman, though he was somebody or other’s heir, so he was titled and tolerated. Then too, the Regent fancied himself quite the patron of the arts, and Harrison enjoyed a certain cachet with the Carlton House set.

“Moreland has three unmarried daughters,” Harrison said. “All pretty, all well dowered, and you’re just trying to decide which one will be the least work.”

If Harrison’s tone had been accusatory, Lionel might have been alarmed, but Harrison spoke as if merely stating facts, and boring facts at that.

Boring, accurate facts.

“You’re trying to decide which one is vain enough to insist on having her portrait painted,” Lionel replied. “Or you might be thinking of approaching His Grace about doing all three, as it were.”

He let the innuendo hang delicately above his spoken words.

“I have never found it attractive in a man to pursue a woman publicly, while privately maligning her. Smacks of… desperation.” Harrison eyed the glass in Lionel’s hand. “Desperation and dishonor. I bid you goodnight, my lord.”

He wafted off, all elegant good looks and sly innuendo, making Lionel long to lift a foot and plant it in the encroaching bastard’s backside. He resisted this urge not because Harrison was right—Lionel was growing desperate and had seldom regarded honor as more than a convenient disguise for bad motives—but he was also intent on having some fun with one of Petersham’s plump, giggling upstairs maids. A public row with a nobody of a painter would queer the chances of that altogether.

![]()

Sir Joseph dawdled for two days. In those two days, he visited regularly with Lady Opie, scribbled off several notes to his London house steward, rode out with his land steward, called on his tenants—again—and otherwise put off a journey he did not want to make.

But had to. His peculiar discussion with Louisa Windham had stuck in Joseph’s mind like the proverbial burr under his saddle. Until he’d spoken the words aloud to her—he required a wife—the need hadn’t been exactly pressing, though it had been nagging. Now, like a sore tooth, it seemed never to leave his awareness.

“When will you be back?”

Amanda, scrambling around on his lap, made the last word into a whine of at least five syllables. “Baa-aaa-aaa-aaa-cck?”

“Yes, Papa.” Fleur clutched his riding jacket in grubby little mitts and started scaling his left knee. “When will you be back?”

“I do not recall inviting either of you to roost upon my person.” Though there they were, each plunked down on her territory of choice, and each smelling of soap, lavender, and something else—mischief perhaps.

“You always go away,” Amanda opined. “But if you didn’t go away, you’d never come see us at all anymore.”

Fleur chimed right in with the chorus. “You used to tuck us in.”

“You used to be infants. Quiet little things who neither slid down banisters nor begged a man for ponies the livelong day.”

Amanda turned big brown eyes on him. “You could bring us ponies for Christmas. We’ve been ever so good.”

“We have,” Fleur concurred. “Nurse hasn’t needed her salts since Monday!”

“Allow me to point out that it’s Tuesday morning.” Joseph gently stopped Fleur from putting her thumb in her mouth. “Don’t get your hopes up that I’ll bring you ponies for Christmas. You’re both too young, and winter is no time to learn to ride.”

Fleur’s chin jutted in an unbecoming manner. “If we were boys, we’d have ponies by now.”

Amanda nodded vigorously, dark curls bouncing. “Fleur is right. If we were boys, you’d listen to our lessons.”

“If you were boys, you could inherit a damned title.”

The words were out, muttered, but far too inappropriate for tender ears to have missed a single syllable.

“Papa said damn.” Fleur slapped her hand over her mouth as if to hold back her giggles. “Damn is a bad word. We’re not supposed to say damn, or damn it, or God damn it to hell, or—”

“Cease.” Joseph wrapped an arm around her to put his much-larger hand over her mouth. He was outnumbered, though, and Amanda started up immediately.

“Or bloody damn or damn and blast. If we were boys, you’d teach us how to swear and even belch, and we’d know how to far—”

He ended up with two little girls wiggling off his lap, their giggles cascading behind them as they scampered a few feet away.

“Enough, the both of you.” He rose to his full height and scowled down at them. “This is no way to earn anything but a lump of coal in your stocking. When I return from Town, I’ll expect perfect deportment from each of you, glowing reports from the maids and Miss Hodges both, and no more of this riot and insurrection.”

They quieted immediately at his tone, their smiles turning to looks of uncertainty aimed at him and then at each other.

While Joseph felt again that sinking in his middle that suggested he was not fit to parent these children—not fit in the least—much less another dozen whom he saw only on occasion.

He went down on one knee, unable to tolerate the possibility that those uncertain looks would degenerate into quivering chins and—he shuddered at the very notion—a double spate of female tears. “Give me a farewell kiss, and I’ll be on my way. Say your prayers while I’m gone, don’t tease each other too mercilessly, and mind Miss Hodges.”

“Yes, Papa.”

He held out his arms, and the girls advanced, first Amanda—the elder, the one who elected herself in charge of taking risks—then Fleur, the loyal follower. They dutifully bussed his cheek, and he let them go.

“And stay off the banisters.”

There being nothing more to say, he left the nursery, mounted his horse, and pointed his gelding in the direction of London. The roads were dry, the weather fair, and Joseph’s horse—after about five miles—apparently in the mood to behave, which left Joseph to the task of brooding.

He did not require a wife, but his dependents needed an adult female to take them in hand, and thus a wife he would get. His wife would know what to do with Miss Hodges, whom Joseph had overheard lamenting again the “plebeian” coloring exhibited by Sir Joseph’s daughters.

Dark hair and dark eyes hadn’t been the least plebeian on King Charles II or his Iberian wife, had they? Females nowadays were held to some other standard, one which maintained that fair hair and fair skin were pretty, while dark hair…

Louisa Windham had dark hair and dark eyes, and on her, the combination was… lovely. She was not a restful woman, having about her a faint air of discontent, of boredom, perhaps. But it was to Louisa Windham that Joseph had articulated the need for a wife, and to her he’d admitted that the title was figuring into his thinking.

The title.

Cousin Sixtus Hargrave Carrington had written to warn Joseph that he was not enjoying good health. To receive the annual letter so many days before Christmas was only to underscore the point: Sixtus did not expect to live out the year.

Any party holding at least a one-third interest in a title in abeyance could petition to have that title bestowed upon him. Hargrave and Joseph, though each held an equal claim, had by tacit agreement declined to petition for a choice to be made between them. Upon either man’s death without male issue, the other fellow would be saddled with the title.

And that… Joseph thought of his relief when Lady Louisa had spared him having to clomp and mince through a promenade—or perhaps spared herself. He thought of his offering to recite poetry to give them both a reprieve from his attempts at polite conversation. He thought of his daughters at the mercy of an employee who didn’t even approve of their coloring—something neither child could help or control.

“My life is not a fairy tale,” Sir Joseph informed his horse, “but it’s quite bearable. I can provide for my dependants. I have a measure of privacy and can, on occasion, steal away to read to an appreciative audience.”

The horse snorted.

“Very well, a tolerant audience.”

A mere knight could limp; a lord must waltz. A mere knight could read Shakespeare to his favorite breeding sow; a lord was likely forbidden to have a favorite breeding sow. A mere knight could admire a lovely, dark-haired lady from afar, while a lord…

A lord had a title and a succession to attend to, so he must—he absolutely must—have a lady to bear him sons.

Joseph urged his horse from the trot into a rocking canter and put all thoughts of ladies and waltzes from his mind, the better to allow him to pray for his fourth cousin’s immediate return to good health.

![]()

“My love, I thought you’d be going out this morning.” As he spoke, His Grace, the Duke of Moreland made an instantaneous assessment of the slight frown on his duchess’s brow and changed course to join her in her private sitting room. He saw the frown disappear and closed the door behind him.

Whatever was troubling his bride of more than three decades, she was going to try to hide it from him. Silly girl. If the huntsman had blown “gone away,” His Grace would not have felt any stronger need to pursue and investigate.

“Is there fresh tea?” he asked, taking a place beside his duchess.

But Her Grace was no fool. She knew that in the duke’s eyes, the purpose of tea was to wash down crème cakes. In extremis, tea might serve as an adequate medium in which to stir a generous dollop of brandy on a freezing day.

Tea for its own sake was a lame undertaking, and Her Grace had long since divined His Grace’s position on the matter.

“I sent Westhaven and Anna off shopping with the girls,” Her Grace said. “Eve tried to beg off, but her sisters wouldn’t have any of that.”

“Abandoning you to my dubious company.” And abandoning him to the dubious offerings on the tea tray: Scones and butter, jam, and honey. Not even a hot cross bun or a few slices of stollen. “Whom do you suppose will make our stollen this Christmas, since Sophie has gone to housekeeping with her baron?”

“Just where do you think Sophie got her recipe, Moreland?”

He adored it when she called him Moreland in that magisterial tone. He planted a kiss on her cheek. “From your mother, because your interest in cooking is almost equal to my interest in a tepid cup of tea. What has given you a fit of the megrims, my love? Shall I take you for a drive? Send around to Gunter’s for a picnic?”

“Louisa asked me if she might remain at Morelands next spring.”

His Grace sat back, trying to shift mentally to that part of his intellect—the brilliant politician and successful former cavalry officer part—that occasionally got him past the rough patches when the papa part was knocked on its backside.

He reached for his wife’s hand, needing the subtle information gathered by physical connection with her—and the reassurance. “What is that about, Esther? Louisa is not the least retiring and not the type to mope.”

But Louisa was from that vast, unmapped territory known as His Daughters. His Grace loved his five adult daughters and would cheerfully have died to protect them, but as for understanding them… He might as well have tried to grasp the mental processes of… another species entirely.

“I have been thinking this over,” Her Grace said, “and you’re right. She’s not the type to mope. She takes after her papa in that she’s more given to action than introspection.”

“You have referred to me as a bull in a tea shop in your more honest moments, Esther.”

“A handsome bull.” She moved closer in that subtle way women had of shifting without being visible about it. “A doting and lovable bull, one who keeps me quite pleased with him, usually.”

“Such flattery will have me locking that door, Esther Windham.” A quarter century had passed since they’d needed any locked doors in the middle of the day, but mistletoe was showing up all over the house, and standards had to be maintained if his duchess was to be kept smiling a particular smile.

She cocked her head, the beginnings of that smile lurking at the corners of her mouth. “About Louisa.”

His Grace understood priorities, for they were the heart and soul of bearing a lofty title. Comforting his duchess involved more than just flirting with her. He slipped an arm around her waist, the better to allow her head to rest on his shoulder.

“About our dear Louisa,” His Grace said, pressing a kiss to his duchess’s brow. “As pretty a young lady as ever sipped the punch at Almack’s. She is worrying you, and thus I must be worried, as well.”

“I have grasped her reasoning, I think, but you must tell me your thoughts. I believe, as the oldest unmarried daughter, she thinks to remain at Morelands so as not to overshadow her younger sisters.”

His Grace stroked a hand over his wife’s wheat-gold hair while he considered her theory. He was careful not to disturb her coiffure—a man married to a duchess learned the knack of such things.

“Your thinking is logical, and Louisa is logical. There are still many people who believe daughters ought to marry in birth order or not at all. I will say again that Louisa should have been a cavalry officer. She has the gallantry for it and the excellent seat.”

“Also the outspoken opinions and tendency to take charge of matters outside her authority.”

“You can’t blame the girl if she takes after her mama in some regards.”

Esther sat forward and aimed a glare at him, until he smiled at her ruffled feathers. She smiled too and subsided against him. “Shameless man, and you a duke.”

“Also a father. Have you spoken to Louisa about her wayward notions? She cannot be allowed to give up so soon, Esther. Young men are blockheads. This is known to all save young men themselves, and Louisa is not one to tolerate blockheadedness from any quarter.”

“Percival, what if Louisa is right?”

The little note of despair in his duchess’s voice sent alarm skittering through His Grace’s vitals. “Right? To give up the chase after what, only three Seasons? That is rot, utter tripe, Esther, to think—”

She put her fingers to his lips, giving him the scent of roses and the sensation of soft, soft skin against his mouth. “Six Seasons, Percival. Six Seasons, which means for five Seasons she’s had to stand around with her empty dance card, secure in the knowledge she has not taken, convincing herself all the while that it’s her fault her sisters have not married.”

Her Grace was being reasonable. She was at her most dangerous when she was being reasonable.

“Maggie was past thirty when she married, my love. Men are idiots, is the trouble. We need time to mature beyond the screaming demands of our base natures, to appreciate a woman’s—”

He fell silent. He’d been such an idiot, and only by the grace of a merciful God and the cleverness of his dear duchess had he been spared the marriage from hell.

“I don’t want to give up on her either, Percival, for Louisa has a soft heart and would make a wonderful wife and mother, but to see her tortured, Season after Season…”

Tortured. Tortured was not a word a father liked to hear regarding any of his offspring, but most especially not his pretty, proud, and—facing facts was also part of being a duke—sometimes blunt-to-a-fault daughter.

“She dances well.” He needed to defend Louisa, even to her mother.

“With the few who ask her.”

“She’s fluent in any number of languages.”

“So why hasn’t she singled out some diplomat? They tend to be from good families, and we’ve certainly seen enough of them underfoot in recent years.”

“She’s very well read.”

“Appallingly so, some would say.”

“She understands mathematics better than any Oxford don.”

“Percival, that is hardly an attribute that will secure her a happy future.”

His Grace rose from the sofa, needing to pace in the face of such honesty. “It isn’t Louisa’s fault she’s got a brain. It isn’t her fault she isn’t dainty and blond and simpering. You never simpered, Esther, and no woman of your magnificent height could be called dainty.”

Refined, yes—Her Grace managed that easily—but she was not dainty.

“I never asked Lord Hubert if I might try a puff of his cigar, either.”

“Hubert is eighty if he’s a day. How else is a young lady to flatter and flirt with such a curmudgeon?” Except old Hubert in his cups had a puerile turn of mind, and a puff of his cigar had—several brandies later—turned into a much more prurient innuendo. His Grace shuddered to recall the quiet talk he’d had with the man in the sober light of day.

Her Grace arranged her skirts in a sniffy sort of way. “I never threatened to get my curricle to Brighton in record time, arguing that a woman’s lighter frame would give her an advantage of weight not enjoyed by the overfed dandies of the Carlton House set.”

“She didn’t mean to insult the Regent.” And thank God the Regent remained too convinced of his own dashing good form to take it that way.

“Percy, in six years, the young men have not learned to appreciate Louisa, but it’s also true that she hasn’t moderated her ways much at all.”

“She should not have to.” He resumed his seat beside his wife. “She is brave, she’s intelligent, she’s loyal as hell—witness this sacrifice she’s trying to make for her sisters. We must find her a fellow, Esther.”

The duchess’s brows rose, indicating that His Grace had leapt to a different conclusion than his wife had been leading him to. His Grace’s gratification was probably akin to what the fox felt when twenty couple hounds went off baying at the top of their lungs after some deer or rabbit.

Her Grace did not take his hand or put her head on his shoulder. “I was thinking more in terms of allowing her to stay with Sophie and Sindal for a bit, or perhaps excusing her from next spring’s Season entirely.”

“It might come to that, but first, let’s investigate the other options, shall we?”

He poured his wife a steaming cup of tea, prepared it exactly to her liking, and passed it to her without pouring one for himself. “We will find her a fellow among those in Town anticipating the holiday season. We must simply apply ourselves. There’s plenty enough to choose from—how hard can it be to find one bridegroom between now and Christmas?”

End of Excerpt

Lady Louisa’s Christmas Knight is available in the following formats:

- Barnes & Noble Nook

- Kobo

- Apple Books

- Amazon Kindle

Digital:

Print:

- Kobo UK

- Booktopia AUS

- Amazon Kindle UK

United Kingdom:

- Bookshop

- Tantor Publishing

- Apple Books

- Libro.fm

- Audible

- Amazon Audio

- AudiobooksNow

- Books-A-Million

- Chirp

- Hoopla

- Kobo

- Nook Audiobooks

Audio:

For those who patronize public libraries, this title has also been uploaded to Overdrive, Hoopla, Baker & Taylor, and many other library channels. You can see the full list of library distributors here.

Listen to a Snippet:

Connected Books

Lady Louisa’s Christmas Knight is Book 6 in the Windham series. The full series reading order is as follows:

- Book 1: The Heir

- Book 2: The Soldier

- Book 3: Lady Sophie’s Christmas Wish

- Book 4: The Virtuoso

- Book 5: Lady Maggie’s Secret Scandal

- Book 6: Lady Louisa’s Christmas Knight

- Book 7: Lady Eve’s Indiscretion

- Book 8: Lady Jenny’s Christmas Portrait

- Novella: The Ducal Gift and The Christmas Carriage

- Novella: The Windham Ducal Duet

- Novella: Windham Family Duet

Bonus Material

-

Windham Family Tree →

-

Deleted Scene from Lady Louisa’s Christmas Knight →

As an author, I like to hear from various Windham siblings no matter whose love story I’m telling. Too much of that though, and the book can lose focus—there being eight siblings to hear from. What mattered in this scene was to convey to the reader that Louisa’s siblings knew Sir Joseph was falling for her, that Lionel was in need of coin, and that Lionel was in a position to know some of Joseph’s personal circumstances. All of those plot points could be worked into the story without indulging in a scene in Eve’s point of view. I consoled myself with the knowledge that Eve’s book would come out next…